On 22 June 2011

in Vienna, the President of Austria awarded a Scottish

constitutional expert and writer the Cross of Honour in Gold for

Services to the Republic of Austria (Das Goldene Ehrenzeichen

für Verdienste um die Republik Österreich). The ceremony in the

historic Congress Hall of the Ballhausplatz, where the Congress

of Vienna was held in 1814/15, was attended by two British

ambassadors amongst other VIPs. This was in recognition of his

work in compiling the Austrian Foreign Policy Yearbook for 16

years, and his previous 15 years as editor of the government’s

foreign affairs magazine Austria Today, as well as numerous

special assignments, many of them still highly confidential, on

behalf of the Republic.

Dr James Wilkie

Dr James Wilkie

was born in Glasgow and brought up in Clydebank, Helensburgh,

Garelochhead and Clynder. After working in local government for

a time (libraries, youth and community and probation work), he

studied at Strathclyde University and Jordanhill College before

entering the teaching profession. He was simultaneously active

in the Boys’ Brigade, becoming vice-president and secretary of

the Clydebank and District BB Battalion. He maintained a

life-long love of mountaineering and sailing which eventually

led to his climbing all of Scotland’s Munros as well as doing

spectacular ascents in the High Alps. This was put to good use

in his 11 years as administrator of the Duke of Edinburgh’s

Award, when he conducted all the silver and gold expedition

tests personally. A later climbing companion was Professor

Malcolm Slesser, with whom he often sailed off the west coast.

As holiday crew on a fishing boat he got as far as St. Kilda and

other remote islands.

His mother’s

family contacts with the famous medical school of Vienna

University, and also his wife’s connections there, led him to

accept an offer in 1968 to study for a Doctor of Philosophy

degree in Vienna, his chosen subject being constitutional

history. One of his seminar leaders at the university in 1970

was the newly elected Austrian Chancellor, Dr. Bruno Kreisky.

That led to a friendship between the statesman and his Scottish

student. Bruno later had Wilkie undertake recurring work for

the Chancellery and the Foreign Ministry, where Jim’s bilingual

skills in English and German were helpful in preparing

diplomatically sensitive policy statements and speeches.

After receiving

his doctorate Jim Wilkie returned to Scotland. He taught history

at Allan Glen’s School in Glasgow and Camphill High in Paisley

as well as resuming his outdoor and mountain leadership

activities. But opportunities were opening up for him in

Austria and he returned there to undertake teaching and writing

assignments. Dr Wilkie worked in broadcasting in Vienna in 1977

and assisted in some secondary schools, including residential

skiing courses in the Alps.

In 1980 he was

invited to become editor of the country’s diplomatic journal

Austria Today, which was published in English, French and German

editions, and which involved numerous special assignments for

Chancellor Kreisky personally. That work, based in the Hofburg

palace, was to continue for 15 years, in three languages daily,

despite his congenital deafness that eventually made classroom

work impossible. Austria Today published quality articles and

papers on the country’s progress in science, industry, the arts,

and diplomatic affairs, and circulated among the top people in

144 countries.

His special

assignments included a “fire brigade” action to assist the

International institute for Applied Systems Analysis, after an

espionage affair had caused considerable damage there. He wrote

IIASA’s 1985 and 1986 annual scientific reports, and remains a

member of the worldwide IIASA Society. He also, at Kreisky’s

request, assisted the Palme Commission on Disarmament, the

forerunner of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in

Europe (OSCE), now Europe’s largest political institution.

In 1988 Dr Wilkie,

at the request of Foreign Minister Alois Mock, founded the

Austrian Foreign Policy Yearbook, the official statement of

foreign policy, based on the Foreign Ministry’s departmental

papers, which he continued to edit for 16 years. As editor of

those journals Dr Wilkie attended many international conferences

on security and regional cooperation, including EU and Council

of Europe summits.

James Wilkie

however, maintained his love for Scotland, to which he regularly

commutes to engage in sailing and mountaineering as well as

visiting family and friends. He was elected a member of both the

Scottish Mountaineering Club (SMC) and the prestigious Austrian

Alpine Club (Österreichischer Alpenklub), which is twinned with

the SMC, amongst many others. Having studied piano at the Royal

Scottish Academy of Music, he also became a member of the Royal

Scottish Country Dance Society. From 1973 to the present he has

been a regular contributor to the Scotsman letters pages, and

more recently to its Internet web pages.

A growing

interest in politics led to membership of the Scotland UN

Committee and to attending United Nations meetings on their

behalf. In cooperation with S-UN secretary John McGill of

Kilmarnock he drafted the documentation for the Council of

Europe that led to the restoration of the Scottish Parliament.

With the devolution programme completed, he was asked to accept

the position of Chairman of the Scottish Democratic Alliance (SDA),

which researches the future governance, defence and other

policies of an independent Scotland. He is particularly active

on EU fisheries policy in cooperation with the Scottish

fishermen’s representatives.

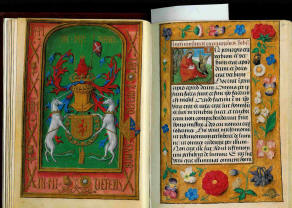

Dr Wilkie was

able to bring his Austrian and Scottish interests together in a

project financed by Austria to make exact facsimile

reproductions of a remarkable Scottish document, the Book of

Hours of King James IV. It had been produced in 1503, but was

lost to Scotland after the death of James IV at Flodden. His

widow, Margaret Tudor, passed it on to her sister Mary Tudor,

who may have taken it to France. The Book of Hours then

re-surfaced in the Habsburg collection in Vienna during the 17th

century, and is now in the Austrian National Library. The new

reproductions were a project by ADEVA, the Academic Printing and

Publishing Institute of Graz. 700 copies were printed,

containing the meticulously reproduced 480 full colour folio

pages of this invaluable component of Scotland’s heritage. Dr.

Wilkie contributed the learned article on the historical

background for the accompanying volume.

In its content,

the Book of Hours of James IV resembles a medieval prayer book

and calendar of religious feast days. It has magnificent colour

and gold leaf decorated pages with intricate designs and

reproductions of Biblical symbols, including the famous portrait

of James himself wearing the pre-1540 Crown of Scotland, and the

funeral of his father, James III. King James is believed to have

financed its publication himself to commemorate his marriage to

Margaret Tudor, a daughter of King Henry VII of England, who is

also depicted in the book.

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

Jim Wilkie went

on to compile the official book on the Kaiservilla palace at Bad

Ischl, the summer capital of the Habsburg Monarchy. He is a

close friend of the Habsburg family, with whom he regularly

stays in Ischl. His son, Dr. Alexander Wilkie, is godfather to

the Habsburg heir, Archduke Valentin.

In recent years

Dr Wilkie has undertaken work for the United Nations UNIDO and

UNOOSA organisations, and still retains his UN pass. For UNIDO

he assisted the preparation of environmentally beneficial

development projects in 8 African and 5 SE Asian countries.

Under the auspices of UNOOSA, the UN Office on Outer Space

Affairs, he helped compile and edit satellite surveys of the

world’s freshwater resources, its mega-cities, and the European

woodlands, amongst others. There was also a comprehensive

satellite survey of Saudi Arabia, an archeological survey of

Syria, etc. On the strength of his Scottish teaching

qualification he edited the world’s first initial training

scheme for space technologists in cooperation with the Geospace

organisation and the European Space Agency.

The rare award of

the magnificent Cross of Honour in Gold for Services to the

Republic, the highest order in the Ritterkreuz class, is a quite

remarkable honour for a Scot. James Wilkie is married to an

Austrian, Claudia, whom he met some 40 years ago when she was a

teacher in Bearsden Academy, and he has contributed

significantly to Austria’s image and policies through his

numerous publications as well as through his work with OPEC and

with United Nations agencies in Vienna. He well deserves the

honour.

As a reciprocal,

he has worked quietly behind the scenes to obtain cooperation in

and understanding of Scottish affairs, from the Republic of

Austria and from other states in Europe and Scandinavia, whose

representatives he meets through the Foreign Policy Association

in Vienna. In an astonishing career, for which the word unique

borders on understatement, he has pioneered Scotland’s way back

to Europe as a chapter in its long history closes and a new one

opens.

The James IV Book of Hours

The Historical

Background

By James Wilkie

Download

an updated article about this book here

The Book of Hours of James IV, King

of Scots, is rightly regarded as one of the supreme examples of

late mediaeval manuscript illumination. Yet it is more than

simply that, for it also documents a momentous event in the

history of the Kingdom of Scotland, an event that was to have

far-reaching effects on the course of history for centuries to

come.

There is no identifiable reference

to this book in the state treasurer’s accounts, and it is

possible that James paid for it personally, and not out of

public funds. The accounts do, in fact, mention works of this

type that were ordered from Flemish artists, indicating that the

artists had quite a flourishing trade in commissions for

Scottish clients. It might be asked why this was the case, since

some excellent work of this type had been produced in mediaeval

Scotland, especially in the monasteries with their fine

tradition of Celtic art. The answer is to be found not only in

the international reputation of the Netherlands school of book

illumination, but also in the political background.

For two centuries the Kingdom of

Scotland had been in continual upheaval due to the unceasing

English attempts at military conquest after the takeover of

England by the aggressive Norman dynasty in 1066. Having overrun

Wales and Ireland, the English had turned their attention to

Scotland in the late 13th century. There, however,

they had met their match when, after two decades of guerrilla

warfare, a huge English army was annihilated at Bannockburn in

1314 by a Scottish force only a fraction of its size. The

English, after the greatest military defeat in their entire

history, then tried to attain their ends by international

diplomacy, which the Scottish leaders countered with their

famous letter to the Pope – the then international authority –

in 1320; now known as the Declaration of Arbroath, its most

famous passage states:

„For so long as a hundred of us

remain alive we will never subject ourselves to the dominion of

the English. We fight not for glory or riches or honours, but

for freedom alone, which no good man will relinquish, except

with his life.“

In 1328 the English were finally

obliged to sign the Treaty of Northampton, acknowledging

Scotland’s total independence and abandoning all English claims

upon it. And still they did not give up their attempts at

conquest. Time and again armies were sent into Scotland,

attempts were made to set English puppets on the Scottish throne

by force of arms, or to have the heir or heiress to the throne

forced into a dynastic marriage with England.

All of these attempts were

successfully resisted by the Scots, but at a price. The warfare

and foreign depredations, with no really stable period of peace

for several centuries, undoubtedly impoverished the country,

economically and culturally. The huge price of ransoming

national leaders from English captivity, the burning of

monasteries and other economic and cultural centres by the

English, or the “scorched earth” policy pursued by the Scots to

deny the invaders any means of living off the land – all this

not only hindered the development of an orderly agricultural

system but also of the country’s fine mediaeval artistic

tradition.

The result of this situation was

that for almost 400 years Scotland’s economic and cultural links

were predominantly with the continent of Europe, with the Baltic

region, the Netherlands, and with France. Above all, the

military alliance with France against England, with the promise

of mutual assistance in the event of English aggression, put its

stamp on the political situation for most of that period. The

Hundred Years War, which ended with the failure of the attempts

to bring France under English rule, took a certain amount of

pressure off Scotland, since the English generally found it more

attractive to pluck the rich French lily than to struggle with

the recalcitrant Scottish thistle.

The Stewart dynasty came to the

throne of Scotland in 1371, and was to rule until l714. Walter

the High Steward, one of the great officers of state, had

married Margery Bruce, daughter of the national hero, King

Robert I, the victor of Bannockburn, and when the direct male

line of succession failed it was their son who inherited the

throne. The Stewarts were good and competent rulers on the

whole, but the country was bedevilled by a succession of

minorities when young children inherited the throne after the

sudden deaths of their fathers. For example, in 1406 King James

I, at the age of 12, was sent off to France for his safety, but

was captured at sea by English pirates during a period of agreed

truce and held captive in England for 18 years, the country

being ruled by regents in his absence. He was eventually

released by the English king on payment of a huge ransom by the

Scottish parliament.

It is an illustration of the

situation that, stung by the successes of the Scottish regiments

fighting for the French against England, the English king Henry

V took the captive King of Scots with him to France und made him

witness the execution of a number of his captured countrymen, on

the spurious ground that they had committed “treason” by

fighting against their king. The Scottish regents and

parliaments, for their part, not only pursued the war, but also

carried on a vigorous diplomatic campaign to unite the often

divided French factions in the common struggle.

One of these was the Duke of

Burgundy, the ruler of a state that had originated as a feudal

grant of territory to the younger son of a French king, but

which through further territorial acquisitions was well on the

way to becoming in its own right one of the major powers in late

mediaeval Europe. At the height of its power, Burgundy extended

from Lake Geneva to the north of Holland, and from the Black

Forest to west of Boulogne on the Channel coast, including the

whole of Flanders and the Netherlands. Its rich cultural life

was largely founded on the prosperity of the trading cities in

Flanders, where the Scottish merchants had their main export

markets. The enormous wealth of the Burgundian ducal court

enabled it to exercise a munificent patronage of the arts, which

was seen in the court musical tradition as much as in Dutch

painting and Flemish illuminated books.

Four of James I’s daughters made

important dynastic marriages in Europe, one of them marrying the

Dauphin of France, while another became Duchess of Austria.

Their brother, James II, King of Scots, took a princess of the

rich and powerful House of Burgundy as his queen consort in

1449. Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, with the concurrence of

King Charles VII of France, arranged the marriage of his niece,

Mary of Guelders, to the Scottish monarch. This was a union

devoutly desired by the Scots, with their important commercial

interests in the Low Countries. It was no less desired by the

Burgundians and French for obvious strategic reasons, above all

the need to maintain a ring of steel around the English. The

clause in the marriage treaty that provided for perpetual

friendship and alliance between Scotland and Burgundy was one

that allowed Scottish merchants a favourable status in all the

Burgundian dominions. The Scots made full use of their

preferential rights.

James II, a capable and popular

monarch, died an unusual death. While besieging Roxburgh Castle

in 1460 in order to drive out the last remnants of the English

invaders, he ordered his artillery to fire a salute to mark the

arrival on the scene of his queen, Mary of Guelders, with the

result that he was killed when the heavy siege cannon next to

which he was standing burst and he was hit by shrapnel. His army

recaptured Roxburgh and drove the English out, but Mary of

Guelders had to govern Scotland together with a regency council

in the name of her young son James III. This had administrative

drawbacks, but the preferential Scottish commercial and cultural

links with the Burgundian empire in the Netherlands naturally

remained unimpaired.

The links with Burgundy continued

even after James III made a dynastic marriage with Princess

Margaret of Denmark, and thereby gained the Orkney and Shetland

Islands for the Kingdom of Scotland. Mary of Guelders continued

to exert her own and Burgundy’s influence, most notably after

the so-called Wars of the Roses broke out between the rival

claimants to the throne of England, and the Duke of Burgundy

supported the Yorkist cause.

This time it was the turn of

prominent English royal fugitives to seek asylum in Scotland.

The Burgundian influence was documented in the altar portraits

of James III and Margaret of Denmark by Hugo van der Goes for

the Collegiate Church of the Holy Trinity in Edinburgh. Now in

the National Gallery of Scotland, this altarpiece very obviously

influenced the artist who did the James IV Book of Hours.

A new age dawned in 1485 when the

Wars of the Roses in England ended with the victory of Henry

Tudor at the battle of Bosworth, with the assistance of French

and Scottish military forces. The Norman ruling dynasty was at

an end, for Tudor was a Welshman, of Celtic blood, with the will

to establish peaceful relations with Scotland. A large Scottish

delegation attended his coronation as Henry VII, King of

England, and for the first time in two hundred years the kings

of Scotland and England were prepared to sit down together and

discuss common problems. James III had two matters he wanted to

discuss with Henry.

The first one was the question of

the town of Berwick on Tweed, Scotland’s major seaport, through

which much of the trade with the Netherlands was carried on, and

which had been occupied by an English army toward the end of the

previous regime. The other was the matter of dynastic marriages

for himself – Margaret of Denmark having died in the meantime –

and his son James, Duke of Rothesay, the heir to the Scottish

throne. He was not granted time to do either.

There were factions in Scotland who

were not happy about having Scotland’s richest town freed from

English occupation only to strengthen the king’s position.

James’s heavy-handed methods of asserting the royal authority

over the powerful nobility had made him many enemies, and now

that there was unaccustomed peace on the frontier with England

many of those who had spent their whole lives in military

service found themselves at a loose end. In March 1488 an

insurrection broke out against James, with the 15-year-old

James, Duke of Rothesay, as the figurehead of the rebel lords.

It came to an open battle at Sauchieburn, near Stirling, with

the crown prince’s forces flying the royal standard against the

king, his father. James III survived the defeat of his forces,

but was killed by an unknown hand after the battle. His son

carried an iron belt or chain about his waist for the rest of

his life, in expiation of the crime against his father.

The reign of James IV was

nevertheless one of the most brilliant high points in the long

history of the ancient Kingdom of Scotland, but it was to end in

dreadful disaster. James, born in 1472, reigned from 1488 to

1513. This internationally highly regarded renaissance prince

was an educated, imaginative and energetic ruler in the

patriarchal tradition of the Scottish monarchy.

He succeeded to the throne at the

age of 15. James, however, took a firm grip of his kingdom,

quelled all intrigues, and for 25 years ruled in harmony with

parliament and people. His court, possibly influenced by his

Burgundian family connections, was the cultural centre of the

land, where literature and art experienced a golden age. James

introduced printing to Scotland, the University of Aberdeen was

founded in 1494, and the Royal College of Surgeons in 1506. In

1496 the Scottish parliament passed the first compulsory

education act, which laid down that the children of the barons

and freeholders had to attend school. His efforts to protect the

Christian religion led Pope Julius II to present James in 1507

with the Scottish Sword of State – which can still be viewed

along with the Scottish Crown and the other regalia in Edinburgh

Castle, including the State Sceptre presented to James by Pope

Alexander VI in 1494. James passionately desired to lead a

European crusade to the Holy Land, but the age of crusades had

already passed and his early death eventually ruled out any such

proposition.

Unfortunately, however, there

existed barely-concealed hostility between James and Henry VII

of England – not surprisingly, in view of Henry’s previous good

relationship with James’s murdered father. The various truces

with England did not prevent James from maintaining the

traditional alliance with France, and leading his army over the

border on a number of occasions in support of his French allies,

or of a pretender to the English throne. Nor did they prevent

unofficial Scottish-English warfare at sea. By this time there

were Scottish commercial colonies in Veere, Bruges and other

trading towns of the Netherlands, and a considerable trade with

the rich Burgundian provinces, which had by now come under

Habsburg rule after Maximilian of Austria, later Holy Roman

Emperor, married the heiress Maria of Burgundy in 1477. In order

to protect Scotland’s vitally important trading routes across

the North Sea, James maintained a small but powerful navy,

including his gigantic flagship, the “Great Michael”, which with

a crew of 1,300 men was by far the largest ship in the world at

that time. Clearly, the Burgundian connection was still one of

the major factors in Scottish domestic and foreign policy.

James IV was astute in using his own

marriage prospects as an asset in domestic and foreign politics.

Matches had been suggested with an infanta of Spain or the

daughter of Emperor Maximilian, but James was in no hurry. He

had two brothers to assure the succession, no lack of

mistresses, and already a number of illegitimate children. His

advisers, on the other hand, were becoming impatient, and

James’s latest paramour, Margaret Drummond, died mysteriously

after eating a suspect breakfast. James had already

contemptuously rejected a mere countess offered to him by Henry

VII, and when, after an ominous armed skirmish on the

Scottish-English frontier during a period of truce in 1498, an

English emissary had a private audience with him at Melrose

Abbey, he made it clear that his prior condition for peace and

friendship with England was a marriage between himself and

Henry’s elder daughter, Margaret, then aged nine years old.

Henry VII, an astute statesman, was

well aware that such a match could enable the Scottish ruling

dynasty to succeed to the throne of England, but, as he put it

to his councillors, in that event the greater country would

always predominate in such a union. History was to prove him

right.

The marriage contract was signed in

London on 24 January 1502, when the bride had attained the age

of twelve. Margaret Tudor was to receive lands and castles in

Scotland worth 2,000 pounds sterling annually, and James was to

receive a dowry of 10,000 pounds sterling. A separate treaty of

perpetual peace accompanied the marriage treaty between Scotland

and England, the first one since the Treaty of Northampton in

1328.

Margaret’s journey north for her

wedding was a regal progress, when she was met at the border by

a delegation of the highest nobility of Scotland and escorted to

Dalkeith Castle, where James was waiting to receive her. Four

days later they made their state entry into Edinburgh amid an

ostentatious display of pageantry. The marriage took place on 8

August 1503, in Holyrood Abbey, and was followed by five days of

festivities in James’s new palace of Holyrood House. The poet

William Dunbar composed a famous ode celebrating the marriage of

“The Thistle and the Rose”, the national flowers of Scotland and

England respectively.

James spared no expense for his

wedding. His new gowns cost more than ₤600 each and the wine

bill exceeded ₤2,000 – incredible figures for the time. It is

against this background that one must view the ordering of a

Book of Hours that would adequately reflect the importance of

the occasion – and not least convince the representatives of a

large and powerful country that their princess had made a match

worthy of her status in the smaller neighbouring state. That the

book was ordered from Flanders is least of all surprising in

view of James’s family connections there through his

grandmother, and the massive Scottish commercial interests in

the Low Countries. At any rate, until the death of Henry VII in

1509, the relationship between the kingdoms of Scotland and

England was one of friendship and cooperation, so that one might

reasonably have been led to believe that the hatred of centuries

had been forgotten.

Unfortunately, however, the dynastic

marriage did not lead to lasting peace between Scotland and

England, especially after Margaret Tudor’s unscrupulous brother

ascended the throne of England as Henry VIII. He resumed the

long-standing English attempts to conquer France, whereupon the

French appealed to the Scots for assistance. Under the terms of

the alliance James could not refuse. There was considerable

resistance among the Scottish national leaders, but they

eventually gave way, and James marched his army against the

English. At Flodden, just over the border, he made a stupid

tactical error, and for the first time in his life he lost a

battle. He lost a good deal more, for he himself fell in the

front row of his troops.

That was in 1513, ten years after

the brilliant dynastic wedding. Margaret Tudor, now a widow, did

not go back to England. She remained in Scotland and married for

a second and third time among the Scottish aristocracy. The

beautiful Book of Hours, however, she gave as a present to her

younger sister Mary Tudor. From this point on the book

disappeared from the records until it turned up during the 17th

century in the Habsburg collection in Vienna. In a sense it had

gone home, because the Habsburgs were of course by then the

rulers of the Burgundian empire, including what was to become

known as the “Austrian Netherlands”, later Belgium and

Luxembourg.

It was half a century later that the

first dynastic effect of the marriage was seen. The tragic story

of Mary Stuart (the French spelling of the name, which she

always used) is known worldwide, and has been immortalised in

numerous masterpieces of literature and music. Mary I, Queen of

Scots, was titular monarch since the death of her father, James

V, King of Scots, in her birth year 1541. She ruled Scotland

personally from 1561 till her enforced abdication in favour of

her son in 1567, after which she was held captive in England for

almost 19 years. Her not unjustified claim to the English

throne, which she constantly attempted to realise, stemmed from

the dynastic marriage between her grandparents, James IV and

Margaret Tudor. After several conspiracies against England’s

Queen Elizabeth, whose opponents regarded her as illegitimate,

Mary was condemned to death and beheaded.

The “Marriage of the Thistle and the

Rose” had lasting dynastic consequences exactly one hundred

years later. When the Tudor dynasty in England died out in 1603

with the death of the childless Elizabeth, the heir to the

English throne was none other than James VI, King of Scots, son

of Mary I and great grandson of James IV and Margaret, who

united both crowns in a purely personal union. It took another

century, however, before the constitutional union of the crowns

of Scotland and England took place, when the new United Kingdom

of Great Britain was formed in 1707. By then, however, the Book

of Hours of James IV and Margaret Tudor, that magnificent object

of the Scottish national heritage, already formed part of the

Habsburg Court Library in Vienna, later incorporated into the

Austrian National Library, where it remains to this day.

See

http://www.adeva.at/faks_detail_en.asp?id=49 for a

description of the book.