|

1595, May 26

‘John Gilchrist, Henderson, and Hutton, all three [were] hangit for making

of false writs and pressing to verify the same. Jun. 11. Ane callit Cuming

the Monk [was] hangit for making of false writs.’ —Bir.

July

Two gentlemen of Stirlingshire, one named Bruce, the other Forester,

happened to love one woman, about whom they and their respective friends

consequently quarrelled. At a meeting held by the parties with a view to

composing differences, Bruce was hurt. Then the ‘clannit men’ of the names

of Livingstone and Bruce in the Carse of Faikirk banded themselves

together for revenge. A bailie of Stirling, named Forester, who had had no

concern in the dispute, was soon after about to journey from Edinburgh to

Stirling, when the friends of the deceased ‘belaid all the hieways for his

return.’ Before he had gone many miles, they set upon him, and with sword

and gun slew him. The most remarkable part of the affair was what

followed. Forester being a special servant of the Earl of Mar, it was

resolved that he should be buried with solemnity in Stirling. The corpse

was met at Linlithgow by the earl and a large party of friends, with

displayed banner, and in ‘effeir of weir.’ On their journey to Stirling,

they passed through the lands of Livingstone and Bruce, exhibiting ‘a

picture of the defunct on a fair canvas, painted with the number of the

shots and wounds, to appear the more horrible to the behalders, and this

way they completed his burial.’ —H. K. J.

Another curious circumstance

followed. The parties involved in the homicide had a day of law

appointed for them in Edinburgh, December 20th, and they, in customary

style, summoned their respective friends to be present. A great attendance

was expected; but the Privy Council, knowing there was deadly feid between

a great number of them, ‘feirit that, upon the first occasion of their

meeting, some great inconvenients sall fall out, to the break of his

hieness’ peace, and troubling of the guid and quiet estate of the

country[!], beside the hindering of justice,’ forbade the coming of such

persons to Edinburgh under pain of ‘deid without favour.’—P.

C. R.

Aug 1

Complaint was made to the Town Council of Edinburgh by the corporation of

surgeons, against M. Awin, a French surgeon, for practising his art within

the liberties of the city. He was ordered to desist, under a penalty,

except for certain branches of surgery— namely, cutting for the stone,

curing of ruptures, couching of cataracts, curing the pestilence, and

diseases of women consequent on childbirth.’

Sep

The violences of the age extended even to school-boys.

The ‘scholars and gentlemen’s sons’ of the High School of Edinburgh had at

this time occasion to complain of some abridgment of their wonted period

of vacation, and when they applied to the Town Council for an extension of

what they called their ‘privilege,’ only three days in addition to the

restricted number of fourteen were granted. It appears that the master was

favourable to their suit, but he was ‘borne down and abused by the

Council, who never understood well what privilege belonged to that charge.

Some of the chief gentlemen’s sons resolved to make a mutiny, and one day,

the master being on necessary business a mile or two off the town, they

came in the evening with all necessary provision, and entered the school,

manned the same, took in with them some fencible weapons, with powder and

bullet, and renforcit the doors, refusing to let [any] man come there,

either master or magistrate, until their privilege were fairly granted.’—Pa.

And.

A night passed over. Next morning,

‘some men of the town came to these scholars, desiring them to give over,

and to come forth upon composition; affirming that they should intercede

to obtein them the license of other eight days’ playing. But the scholars

replied that they were mocked of the first eight days’ privilege . . . .

they wald either have the residue of the days granted for their pastime,

or else they wald not give over. This answer was consulted upon by the

magistrate; and notified to the ministers; and the ministers gave their

counsel that they should be letten alone, and some men should be depute to

attend about the house to keep them from vivres, sae that they should be

compelled to render by extremity of hunger.’—H.

K. J.

A day having passed in this manner,

the Council lost patience, and determined to use strong measures. Headed

by Bailie John Macmoran, and attended by a posse of officers, they came to

the school, which was a long, low building standing on the site of the

ancient Blackfriars’ monastery. The bailie at first called on the boys in

a peaceable manner to open the doors. They refused, and asked for their

master, protesting they would acknowledge him at his return, but no other

person. ‘The bailies began to be angry, and called for a great jeist to

prize up the back-door. The scholars bade them beware, and wished them to

desist and leave off that violence, or else they vowed to God they should

put a pair of bullets through the best of their cheeks. The bailies,

believing they durst not shoot, continued still to prize the door,

boasting with many threatening words. The scholars perceiving nothing but

extremity, one Sinclair the chancellor of Caithness’ son, presented a gun

from a window, direct opposite to the bailies’ faces, boasting them and

calling them buttery carles. Off goeth the charged gun. [The

bullet] pierced John Macmoran through his bead, and presently killed him,

so that he fell backward straight to the ground, without speech at all.

‘When the scholars heard of this

mischance, they were ill moved to clamour, and gave over. Certain of them

escaped, and the rest were carried to prison by the magistrates in great

fury, and escaped weel unslain at that instant. Upon the morn, the said

Sinclair was brought to the bar, and was there accused of that slaughter;

but be denied the same constantly. Divers honest friends convenit, and

assisted him. The relatives of Macmoran being rich,

money-offers were of no avail in the case: life for life was what they

sought for. ‘Friends threatened death to all the people of Edinburgh (!)

if they did the child any harm, saying they were not wise that meddled

with the scholars, especially the gentlemen’s sons. They should have

committed that charge to the master, who knew best the truest remedy

without any harm at all.’

Lord Sinclair, as head of the family

to which the young culprit belonged, now came forward in his behalf, and,

by his intercession, the king wrote to the magistrates, desiring them to

delay proceedings. Afterwards, the process was transferred to the Privy

Council. Meanwhile, the other youths, seven in number, the chief of whom

were a son of Murray of Spainyiedale and a son of Pringle of Whitebank,

were kept in confinement upwards of two months, while a debate took place

between the magistrates and the friends of the culprits as to a fair

assize; it being alleged that one composed of citizens would be partial

against the boys. The king commanded that an assize of gentlemen should be

chosen, and, in the end, they, as well as Sinclair, got clear off.

The culprit became Sir William

Sinclair of Mey. He married Catherine Ross of Balnagowan, whom we have

seen unpleasantly mixed up in the charges against Lady Foulis, under July

22, 1590.

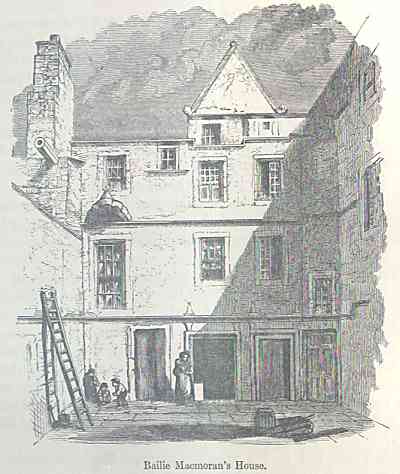

‘Macmoran; says Calderwood, ‘was the

richest merchant in his time, but not gracious to the common people,

because he carried victual to Spain, notwithstanding he was often

admonished by the ministers to refrain.’ It would appear that he had been

a servant of the Regent Morton, and afterwards was what is called a

messenger, or sheriff’s officer. We have also seen that, after the fall of

Morton, he was reported to have been concerned in secreting the treasures

which had been accumulated by his former master.’ His house, still

standing in Riddell’s Close in the Lawnmarket, Edinburgh, gives the idea

that the style of living of a rich Scottish merchant of that day was far

from being mean or despicable.

Sep 22

‘Among the constancies of the court this year, one was remarkable, that at

Glasgow, in September, the king received the Countess of Bothwell into his

favour, the 22d day, at night; and on the 3d of December, again proscribed

and exiled her, under the pain of death; yet gave her a letter of

protection, under his awn hand, within six days thereafter.’—Bal.

This inconstancy is partly explained

away in the Privy Council Record, where it is stated that the countess

abused the privilege of the letter granted to her by going about where she

pleased and vaunting of her credit with the king, while in reality it was

designed only to serve ‘for remaining of herself and her bairns within the

place of Mostour, that her friends might sometime have resorted to her

without danger to his hieness’s laws.’

Oct

James Lord Hay of Yester, brother and successor of the turbulent Master of

Yester already introduced to the reader, kept state in Neidpath Castle,

with his wife, but as yet unblessed with progeny. His presumptive heir was

his second-cousin, Hay of Smithfield, ancestor of the present Sir Adam Hay

of Haystoun. In these circumstances, occasion was given for a curious

series of proceedings, involving the fighting of a regular passage of arms

on a neighbouring plain beside the Tweed—a simple pastoral scene, where

few could now dream that any such incident had ever taken place.

Lord Yester had for his page one

George Hepburn, brother of the parson of Oldhamstocks in East Lothian. His

master-of-the-horse—for such officers were then retained in houses of this

rank—was John Brown of Hartree. One day, Brown, in conversation with

Hepburn, remarked: ‘Your father had good knowledge of physic: I think you

should have some also.’ ‘What mean ye by that?’ said Hepburn. ‘You might

have great advantage by something,’ answered Brown. On being further

questioned, the latter stated that, seeing Lord Yester had no children,

and Hay of Smithfield came next in the entail, it was only necessary to

give the former a suitable dose in order to make the latter Lord Yester.

‘If you,!’ continued Brown, ‘could give him some poison, you should be

nobly rewarded, you and yours.’ ‘Methinks that were no good physic,’ quoth

Hepburn drily, and soon after revealed the project to his lord. Brown, on

being taxed with it, stood stoutly on his denial. Hepburn as strongly

insisted that the proposal had been made to him. For such a case, there

was no solution but the duellium.

Due authority being obtained, a

regular and public combat was arranged to take place on Edston-haugh, near

Neidpath. The two combatants were to fight in their doublets, mounted,

with spears and swords. Some of the greatest men of the country took part

in the affair, and honoured it with their presence. The Laird of Buccleuch

appeared as judge for Brown; Hepburn had, on his part, the Laird of

Cessford. The Lords Yester and Newbottle were amongst those officiating.

When all was ready, the two combatants rode full tilt against each other

with their spears; when Brown missed Hepburn, and was thrown from his

horse with his adversary’s weapon through his body. Having grazed his

thigh in the charge, Hepburn did not immediately follow up his advantage,

but suffered Brown to lie unharmed on the ground. ‘Fy!’ cried one of the

judges, ‘alight and take amends of thy enemy!’ He then advanced on foot

with his sword in his hand to Brown, and commanded him to confess the

truth. ‘Stay,’ cried Brown, ‘till I draw the broken spear out of my body.’

This being done, Brown suddenly drew his sword, and struck at Hepburn, who

for some time was content to ward off his strokes, but at last dealt him a

backward wipe across the face, when the wretched man, blinded with blood,

fell to the ground. The judges then interfered to prevent him from being

further punished by Hepburn; but he resolutely refused to make any

confession.

About this time and for some time

onward, Scotland underwent the pangs of a dearth of extraordinary

severity, in consequence of the destruction of the crops by heavy rains in

autumn. Birrel speaks of it as a famine, ‘the like whereof was never heard

tell of in any age before, nor ever read of since the world was made.’ ‘In

this month of October and November,’ he adds, ‘the wheat and malt at £10

the boll; in March thereafter [1596], the ait meal £10 the boll, the

humble corn £7 the boll. In the month of May, the ait meal £20 the boll in

Galloway. At this time there came victual out of other parts in sic

abundance, that, betwixt the 1st of July and the 10th of August, there

came into Leith three score and six ships laden with victual;

nevertheless, the rye gave £10, 10s. and £11 the boll. The 2 of September,

the rye came down and was sold for £7 the boll, and new ait meal for 7s.

and 7s. 6d. the peck. The 29 of October, the ait meal came up again at

10s. the peck. The 15 of July, the ait meal at 13s. 4d. the peck; the

pease meal at 11s. the peck.

‘In this year, Clement Orr and

Robert Lumsden, his grandson, bought before hand from the Earl Marischal,

the bear meal overhead for 33s. 4d. the boll.’ ‘The ministers pronounced

the curse of God against them, as grinders of the faces of the poor; which

curse too manifestly lighted on them before their deaths.’—Bal.

As usual, the buying up and

withholding of grain with the prospect of increased prices, was viewed

with indignation by all classes of people. The king issued a proclamation

in December 1595, attributing much of the misery of his people to ‘the

avaritious greediness of a great number of persons that has bought and

buys victual afore it come off the grund, and that forestalls and keeps

the same to a dearth,’ and to ‘the shameless and indiscreet behaviour of

the owners of the same victual, wha refuses to thresh out and bring the

same to open markets.’ He threatened to put the laws in force against

these guilty persons, and have the grain escheat to his majesty’s use.

Dec 23

The king professed to be at this time scandalised at the state of the

commonweal, ‘altogether disorderit and shaken louss by reason of the

deidly feids and controversies standing amangs his subjects of all

degrees.’ Seeing how murder had consequently become a daily occurrence, he

resolved upon a new and vigorous effort to bring the hostile parties to a

reconciliation ‘by his awn pains and travel to that effect,’ so that the

country might be the better fitted to resist the common enemy, now

threatening invasion. The Privy Council, therefore, ordained letters to be

sent charging the various parties to make their appearance before the king

on certain days, wherever he might be for the time, each accompanied by a

certain number of friends who might assist with their advice, but the

whole party in each case ‘to keep their lodgings after their coming, while

[till] they be specially sent for by his majesty.’

The groups of persons summoned were,

Robert Master of Eglintoun, and Patrick Houston of that Ilk; James Earl of

Glencairn, and Cunningham of Glengarnock; John Earl of Montrose, and

French of Thorniedykes; Hugh Campbell of Loudon, sheriff of Ayr,

Sandielands of Calder, Sir James Sandielands of Slamannan, Crawford of

Kerse, and Spottiswoode of that Ilk; David Earl of Crawford and Guthrie of

that Ilk; Sir Thomas Lyon of Auldbar, knight, and Garden of that Ilk;

Alexander Lord Livingston, Sir Alexander Bruce, elder, of Airth, and

Archibald Colquhoun of Luss; John Earl of Mar, Alexander Forester of

Garden, and Andro M’Farlane of Arrochar; James Lord Borthwick, Preston of

Craigmiller, Mr George Lauder of Bass, and Charles Lauder son of umwhile

Andro Lauder in Wyndpark; Sir John Edmonston of that Ilk, Maister William

Cranston, younger, of that Ilk; George Earl Marischal and Seyton of

Meldrum; James Cheyne of Straloch and William King of Barrach; James

Tweedie of Drumelzier and Charles Geddes of Rachan. The nobles in every

instance were allowed to have sixty, and the commoners twenty-four persons

to accompany them to the place of agreement, and all, while attending, to

have protection from any process of horning or excommunication which might

have been previously passed upon them. Fire and sword was threatened

against all neglecting to comply with the summons.

Earnest as the king seems now to

have been, and influential as a royal tongue proverbially is, we know for

certain that several of the parties now summoned continued afterwards at

enmity.

1596, Mar 15

‘The king made ane orison before the General Assembly, with many guid

promises and conditions. I pray God he may keep them, be content to

receive admonitions [from the clergy], and be collected himself and his

haill household, and to lay aside his authority royal and be as ane

brother to them, and to see all the kirks in this country weel planted

with ministers. There are in Scotland 900 kirks, of the whilk there are

400 without ministers or readers ‘—Bir

The admonitions which it was so

desirable that the king should receive, were embodied in a paper called

Offences in the King’s House, under the following heads: ‘1. The

reading of the Word, and thanksgiving’ before and after meat, oft omitted.

2. Week-sermons oft neglected, and he would be admonished not to talk with

any in time of divine service. 3. To recommend to him private meditation

with God in spirit and in his awn conscience. 4. Banning and swearing is

too common in the king’s house and court, occasioned by his example. 5. He

would have good company about him: Robertland, papists, murderers, profane

persons, would be removed from him. 6. The queen’s ministry would be

reformed. She herself neglects Word and sacrament, is to be admonished for

night-waking, balling, &c., also touching her company—and so of her

gentlewomen.’—Row.

On the other hand, the king demanded

of this assembly sundry concessions as to his power over the kirk, and

that ministers should not be allowed to meddle with civil affairs or ‘to

name any man in the pulpit, or so vively to describe him as it shall be

equivalent to the very naming of him, except upon the notoriety of a

public crime.’

On this occasion the clergy

denounced the common corruption of all estates within this realm;

namely, ‘an universal coldness, want of zeal, ignorance, contempt of the

Word, ministry, and sacraments, and where knowledge is, yet no sense nor

feeling, evidenced by the want of family exercises, prayer, and the Word,

and singing of psalms; and if they be, they are profaned and abused, by

calling on the cook, steward, or jackman to perform that religious duty .

. . . superstition and idolatry entertained, evidenced in keeping of

festival-days, fires, pilgrimages, singing of carols at Yule, &c swearing,

banning, and cursing: profanation of the Sabbath, especially by working in

seed-time and harvest, journeying, trysting, gaming, dancing, drinking,

fishing, killing, and milling: inferiors not doing duty to superiors,

children having pleas of law against their parents, marrying without their

consent; superiors not doing duty to inferiors, as not training up their

children at schools in virtue and godliness; great and frequent breaches

of duty between married persons: great bloodshed, deadly feuds arising

thence, and assisting of bloodshedders for eluding of the laws:

fornications, adulteries, incests, unlawful marriages and divorcements,

allowed by laws and judges . . . . excessive drinking and waughting,

gluttony (no doubt the cause of this dearth and famine), gorgeous and vain

apparel, filthy speeches and songs: cruel oppressions of poor tenants . .

. idle persons having no lawful callings—as pipers, fiddlers, songsters,

sorners, pleasants, strong and sturdy beggars living in harlotry....

Lying, finally, is a rife and common sin.’

1596, Apr 12

Sir Walter Scott of Branxholm, Laird of Buccleuch, performed an exploit

which has been celebrated both in prose and rhyme.

About the end of January, a ‘day of

truce’ was held at a spot called Dayholm of Kershope in Liddesdale, by the

deputies of the English warden, Lord Scrope, and the Laird of Buccleuch,

keeper of Liddesdale. The Scotch deputy, Scott of Goldielands, had but a

small party—not above twenty—among whom, however, was a noted border

reiver, William Armstrong of Kinmont, commonly known as Kinmont Willie.

The English deputy was attended by several hundred followers. It

happened that, before the end of the meeting, a report came to the English

deputy of some outrages at that moment in the course of being committed by

Scottish borderers within the English line. He entered a complaint on the

subject, and received assurance that the guilty parties should be as soon

as possible rendered up to the vengeance of Lord Scrope.

The day of truce ended peaceably;

but, as the English party was retiring along their side of the Liddel,

they caught sight of the Scottish reivers, and gave chase. Kinmont Willie

was now riding quietly along the Scottish side of the Liddel. Mistaking

him for one of the guilty troop, the English pursued him for three or four

miles, and taking him prisoner, bore him off to Carlisle Castle.

Probably the Liddesdale thief had

incurred more guilt in England than ten lives would have expiated. Yet

what was this to Buccleuch? To him the case was simply that of a retainer

betrayed while on his master’s business and assurance. If the affair had a

public or national aspect, it was that of a Scottishman mistreated, to the

dishonour of his sovereign and country. Having in vain used remonstrances

with Lord Scrope, both by himself and through the king’s representations

to the English ambassador, he resolved at last, as himself has expressed

it, ‘to attempt the simple recovery of the prisoner in sae moderate ane

fashion as was possible to him.’

Buccleuch’s moderate proceeding

consisted in the assembling of two hundred armed and mounted retainers at

the tower of Morton, an hour before sunset of the 12th of April. He had

arranged that no head of any house should be of the number, but all

younger brothers, that the consequences might be the less likely to damage

his following; but, nevertheless, three lairds had insisted on taking part

in the enterprise. Passing silently across the border, they came to

Carlisle about the middle of the night. A select party of eighty then made

an attempt to scale the walls of the castle; but their ladders proving too

short, it was found necessary to break in by force through a postern on

the west side. Two dozen men having got in, six were left to guard the

passage, while the remaining eighteen passed on to Willie’s chamber, broke

it up, and released the prisoner. All this was done without encountering

any resistance except from a few watchmen, who were easily ‘dung on their

backs.' As a signal of their success, the party within the castle sounded

their trumpet ‘mightily.’ Hearing this, Buccleuch raised a loud clamour

amongst his horsemen on the green. At the same time, the bell of the

castle began to sound, a beacon-fire was kindled on the top of the house,

the great bell of the cathedral was rung in correspondence, the watch-bell

of the Moot-hall joined the throng of sounds, and, to crown all, the drum

began to rattle through the streets of the city. ‘The people were

perturbit from their nocturnal sleep, then undigestit at that untimeous

hour, with some cloudy weather and saft rain, whilk are noisome to the

delicate persons of England, whaise bodies are given to quietness, rest,

and delicate feeding, and consequently desirous of more sleep and repose

in bed.’ Amidst the uproar, ‘the assaulters brought forth their

countryman, and convoyit him to the court, where the Lord Scrope’s chalmer

has a prospect unto, to whom he cried with a loud voice a familiar

guid-nicht! and another guid-nicht to his constable Mr Saughell.’ The

twenty-four men returned with Kinmont Willie to the main body, and the

whole party retired without molestation, and re-entered Scotland with the

morning light. ‘The like of sic ane vassalage,’ says the diarist Birrel,

with unwonted enthusiasm, ‘was never done since the memory of man, no, not

in Wallace’ days!’ Buccleuch himself, with true heroism, treated the

matter calmly and even reasoningly. The simple recovery of the prisoner,

he said, ‘maun necessarily be esteimit lawful, gif the taking and

deteining of him be unlawful, as without all question it was.’

The matter was brought before the

king in council (May 25) by the English ambassador, who pleaded that Sir

Walter Scott should be given up to the queen for punishment. It was on

this occasion that the border knight defended himself in the terms above

quoted. Of course his own countrymen sympathised with him in a deed so

gallant, and performed from such a motive, and the king could not readily

act in a contrary strain. Elizabeth never obtained any satisfaction for

the taking of Kinmont Willie.—Spot.

Moy. H.K.J. C.K.S. P.C.R. Bir.

1596, Apr

'.....there came an Englishman to Edinburgh, with a chestain-coloured naig,

which he called Marroco... he made him to do many rare and uncouth tricks,

such as never horse was observed to do the like before in this land. This

man would borrow from twenty or thirty of the spectators a piece of gold

or silver, put all in a purse, and shuffle them together; thereafter he

would bid the horse give every gentleman his own piece of money again. He

would cause him tell by so many pats with his foot how many shillings the

piece of money was worth. He would cause him lie down as dead. He would

say to him: "I will sell you to a carter:" then he would seem to die. Then

he would say: "Marroco, a gentleman hath borrowed you, and you must ride

with a lady of court." Then would he most daintily hackney, amble, and

ride a pace, and trot, and play the jade at his command when his master

pleased. He would make him take a great draught of water as oft as he

liked to command him. By a sign given him, he would beck for the King of

Scots and for Queen Elizabeth, and when ye spoke of the King of Spain,

would both bite and strike at you—and many other wonderful things. I was a

spectator myself in those days. But the report went afterwards that he

devoured his master, because he was thought to be a spirit and nought

else.’ —Pa. And.

This was ‘the dancing horse’ to

which Moth alludes in Shakspeare (Love’s Labour Lost, act I., sc.

2). The actual fate of Banks, the keeper of the animal, was not better

than that which vulgar rumour assigned to him. It is almost an incredible,

yet apparently well-authenticated fact, that horse and man, after

wandering through various countries, were burnt together as magicians at

Rome.

May

At this time, while the country was suffering from famine, there was a

renewing of the Covenant with fasting and humiliation in St Andrews

presbytery. ‘After this exercise,’ says James Melville, one of those

chiefly concerned in ordering it, ‘we wanted not a remarkable effect.’

‘God extraordinarily provided victuals out of all other countries, in sic

store and abundance as was never seen in this land before;’ without which

‘thousands had died for hunger,’ ‘for,’ he goes on to say,

‘notwithstanding of the infinite number of bolls of victual that cam hame

from other parts, all the harvest quarter of that year, the meal gave

aucht, nine, and ten pounds the boll, and the malt eleven and twal, and in

the south and west parts many died’

June 7

Napier, still brooding over the dangers from popery, devised at this time

certain inventions which he thought would be useful for defending the

country in case of invasion. One was a mirror like that of Archimedes,

which should collect the beams of the sun, and reflect them concentratedly

in one ‘mathematical point,’ for the purpose of burning the enemy’s ships.

Another was a similar mirror to reflect artificial fire. A third was a

kind of shot for artillery, not to pass lineally through an enemy’s host,

destroying only those that stand in its way, but which should ‘range

abroad within the whole appointed place, and not departing furth of the

place till it had executed his [its] whole strength, by destroying those

that be within the bounds of the said place.’ A fourth, the last, was a

closed and fortified carriage to bring harquebussiers into the midst of an

enemy—a superfluity, one would think, if there was any hopefulness in the

third of the series. ‘These inventions, besides devices of sailing under

the water, with divers other stratagems for harming of the enemies, by the

grace of God and work of expert craftsmen, I hope to perform." So wrote

Napier at the date noted in the margin. Sir Thomas Urquhart describes the

third of the devices as calculated to clear a field of four miles’

circumference of all living things above a foot in height: by it, he said,

the inventor could destroy 30,000 Turks, without the hazard of a single

Christian. He adds that proof of its powers was given on a large plain in

Scotland, to the destruction of a great many cattle and sheep—a

particular that may be doubted. ‘When he was desired by a friend in his

last illness to reveal the contrivance, his answer was that, for the ruin

and overthrow of man, there were too many devices already framed, which if

he could make to be fewer, he would, with his might, endeavour to do; and

that therefore, seeing the malice and rancour rooted in the heart of

mankind will not suffer them to diminish, the number of them, by any

concert of his, should never be increased.’

June 24

John, Master of Orkney, was tried for the alleged crime of attempting to

destroy the life of his brother the Earl of Orkney, first by witchcraft,

and secondly by more direct means. The case broke down, and would not be

worthy of attention in this place, but for the nature of the means taken

to inculpate the accused. It appeared that the alleged witchcraft stood

upon the evidence of a confession wrung from a woman called Alison

Balfour, residing at Ireland, a village in Orkney, who had been executed

for that imaginary crime in December 1594. The counsel for the Master

shewed that, when this poor woman made her ‘pretended confession,’ as it

might well be called, she had been kept forty-eight hours in the

cashielaws—an instrument of torture supposed to have consisted of an

iron case for the leg, to which fire was gradually applied, till it became

insupportably painful. At the same time, her husband, a man of ninety-one

years of age, her eldest son and daughter, were kept likewise under

torture, ‘the father being in the lang irons of fifty stane wecht,’

the son fixed in the boots with fifty-seven strokes, and the

daughter in the pilniewinks, that they, ‘being sae tormented beside

her, might move her to make any confession for their relief.’ A like

confession had been extorted from Thomas Palpla, to the effect that he had

conspired with the Master to poison his brother, ‘he being kept in the

cashielaws eleven days and eleven nights, twice in the day by the space of

fourteen days callit [driven] in the boots, he being naked in the

meantime, and scourgit with tows [ropes] in sic sort that they left

neither flesh nor hide upon him; in the extremity of whilk torture the

said pretended confession had been drawn out of him.’ Both of these

witnesses had revoked their confessions, Alison Balfour doing so solemnly

on the Heading Hill of Kirkwall, when about to submit to death for her own

alleged crime, of which she at the same time protested herself to be

innocent. These are among the most painful examples we anywhere find of

the barbarous legal procedure of our ancestors.—Pit.

Aug 3

One John Dickson, an Englishman, was tried for uttering slanderous

speeches against the king, calling him ‘ane bastard king,’ and saying ‘he

was not worthy to be obeyed.’ This it appeared he had done in a drunken

anger, when asked to veer his boat out of the way of the king’s ordnance.

He was adjudged to be hanged.—Pit. It is curious on this and some

other occasions to find that, while the king got so little practical

obedience, and the laws in general were so feebly enforced, such a severe

penalty was inflicted on acts of mere disrespect towards majesty.

Aug 17

The court was at this time unable to keep silence under the pelt of

pasquils which it had brought upon itself. We have now a furious edict of

Privy Council against the writers and promulgators of ‘infamous libels,

buiks, ballats, pasquils, and cantels in prose and rhyme,’ which have

lately been set out, and especially against ‘ane maist treasonable letter

in form of a coclcalane, craftily divulgat by certain malicious,

seditious, and unquiet spirits, uttering mony shameful and contumelious

speeches, full of hatrent and dispite, not only against God, his servants

and ministers, but maist ‘unnaturally to the prejudice of the honour, guid

fame, and reputation of the king and queen’s majesties, not sparing the

prince their dearest son, besides their nobility, council, and guid

subjects.’ The only active redress, however, was to proclaim a reward for

the discovery of the offenders.—P. C.

R.

Nov 3

Since November 1585, when he was driven from the king’s councils, James

Stewart of Newton (sometime Earl of Arran) had lived in obscurity in the

north. Now that the Chancellor Maitland was dead, he formed a hope that

possibly some use might be found for him at court; he therefore came to

Edinburgh privately, and had an interview with the king at Holyroodhouse.

He received some encouragement; but as nothing could be done for him

immediately, and there were many enemies to reconcile, he bethought him of

going to live for a while amongst his friends in Ayrshire, trusting

erelong to be sent for.

The ex-favourite was travelling by

Symington, in the upper ward of Lanarkshire, when some one who knew him

gave him warning that he was come into a dangerous neighbourhood, for not

far from the way he was about to pass dwelt a leading man of that house of

Douglas which he had mortally offended by his prosecution of the Regent

Morton. This was Sir James Douglas of Parkhead, whose father was a natural

brother of the regent: he was now the husband of the heiress of the house

of Carlyle of Torthorald, and a man of consideration. Stewart replied

disdainfully that he was travelling where he had a right to be, and he

would not go out of his way for Parkhead nor any other of the house of

Douglas. A mean person who overheard this speech made off and reported it

to Douglas, who, on hearing it, rose from table, where he had been dining,

and vowed he would have the life of Stewart at all hazards. He immediately

mounted, and with three servants rode after his enemy through a valley

called the Catslack. When Stewart saw himself pursued, he asked the name

of the place, and being told, desired his people to come on with all

possible speed, for he had got a response from some soothsayer to beware

of that spot. Parkhead speedily overtook him, struck him from his horse,

and then mercilessly killed him. Cutting off the head, he caused it to be

carried by a servant on the point of a spear, thus verifying another weird

saying regarding Stewart, that he should have the highest head in

Scotland. His body was left on the spot, to become the prey of dogs and

swine.’

Thus perished an ex-chancellor of

Scotland, one who had been permitted for a time to treat the world as if

it had only been made for his own aggrandisement, who had governed a king,

struck down a regent, and made the greatest of the old nobility of the

country tremble. Violence, insolence, and cruelty had been the ruling

principles of his life, and, as Spottiswoode says, ‘he was paid home in

the end.’ No decided effort was made to execute justice upon his slayer,

but it will be afterwards found that the Ochiltree Stewarts did not forget

his death. (See under July 1608.)

Dec 17

An edict of the king against what he called unlawful convocations of the

clergy, had raised a general uneasiness and excitement, many believing

that all independent action of the clergy was struck at. The prosecution

of a minister named David Black, who had slandered the king and queen in

the pulpit, and refused to submit to a secular tribunal, added to the

turmoil. James had further raised a great distrust regarding his fidelity

to the Protestant religion by his allowing the exiled papist lords to

return to their own country. It was at this crisis that the tumult long

known in French fashion as the Seventeenth of December took place.

‘. . . . being

Friday, his majesty being in the Tolbooth sitting in session, and ane

convention of ministers being in the New Kirk [a contiguous section of St

Giles’s Church], and some noblemen being convenit with them, as in special

Blantyre and Lindsay, there came in some devilish officious person, and

said that the ministers were coming to take his life. Upon the whilk, the

Tolbooth doors were steekit, and there arase sic ane crying, "God and the

king !" other

some crying, "God and the kirk !" that the haill

commons of Edinburgh raise in arms, and knew not wherefore always. There

was ane honest man, wha was deacon of deacons; his name was John Watt,

smith. This John Watt raisit the haill crafts in arms, and came to the

Tolbooth, where the entry is to the Chequer-house, and there cried for a

sight of his majesty, or else he sould ding up the yett with forehammers,

sae that never ane within the Tolbooth sould come out with their life. At

length his majesty lookit ower the window, and spake to the commons, wha

offerit to die and live with him. Sae his majesty came down after the

townsmen were commandit off the gait, and was convoyit by the craftsmen to

the abbey of Holyroodhouse.’—Bir.

The king either was really

exasperated or pretended to be so. Retiring to Linlithgow next day, he

sent orders to Edinburgh, discharging the courts of justice from sitting

there, commanding one minister to be imprisoned and others to be put to

the horn, and citing the magistrates to come and answer for the seditious

conduct of their people. Great was the consternation thus produced,

insomuch that one Sunday passed without public worship—’ the like of which

had not been seen before.’ On the last day of the year, James returned, to

all appearance charged with the most alarming intentions against the city.

A proclamation was issued, commanding certain lords and Border chiefs of

noted loyalty to occupy certain ports and streets. There consequently

arose a rumour ‘that the king’s majesty should send in Will Kinmont, the

common thief, as should spulyie the town of Edinburgh. Upon the whilk, the

haill merchants took their haill geir out of their booths and shops, and

transportit the same to the strongest house that was in the town, and

remainit in the said house with themselves, their servants, and looking

for nothing but that they should have all been spulyit. Siclike, the haill

craftsmen and commons convenit themselves, their best goods, as it were

ten or twelve households in ane, whilk was the strongest house, and might

be best keepit from spulying and burning, with hagbut, pistolet, and other

sic armour, as might best defend themselves. Judge, gentle reader, gif

this be playing! Thir noblemen and gentlemen, keepers of the ports and Hie

Gait, being set at the places foresaid, with pike and spear, and other

armour, stood keeping the foresaid places appointit, till his majesty came

to St Giles’s Kirk, Mr David Lindsay making the sermon. His majesty made

ane oration or harangue, concerning the sedition of the seditious

ministers, as it pleased him to term them.’ —Bir.

The affair ended three months after,

in a way that supports the opinion of the Laird of Dumbiedykes, that ‘it’s

sad work, but siller will help it.’ March 22d, ‘the town of Edinburgh was

relaxed frae the horn, and received into the king’s favour again, and the

session ordained to sit down in Edinburgh the 25th of May thereafter.’

Next day, ‘the king drank in the council-house with the bailies, council,

and deacons. The said bailies and council convoyit his majesty to the West

Port thereafter. In the meantime of this drinking in the council-house,

the bells rang for joy of their agreement; the trumpets sounded, the drums

and whistles played, with [as] many other instruments of music as might be

played on; and the town of Edinburgh, for the tumult-raising the 17 of

December before, was ordained to pay to his

majesty thretty thousand merks Scottish.’—Bir.

1596-7

John Mure, of Auchindrain, in Ayrshire, was a gentleman of good means and

connection; who acted at one time in a judicial capacity as bailie of

Carrick, and gave general satisfaction by his judgments. He was son-in-law

to the Laird of Bargeny, one of the three chief men of the all-powerful

Ayrshire family of Kennedy. Sir Thomas Kennedy of Colzean, another of

these great men, was on bad terms with Bargeny. Mure, who might naturally

be expected to take his father-in-law’s side, was for a time restrained by

some practical benefit; in the shape of land; offered to him by Sir

Thomas; but the titles to the lands not being ultimately made good, the

Laird of Auchindrain conceived only the more furious hatred against the

knight of Colzean. This happened about 1595, and it appears at the same

time that Sir Thomas had excited a deadly rage in the bosom of the Earl of

Cassius’s next brother, usually called the Master of Cassillis The Master

and Auchindrain, with another called the Laird of Dunduff, easily came to

an understanding with each other, and agreed to slay Sir Thomas Kennedy

the first opportunity. Such was the manner of conducting a quarrel about

land-rights and despiteful words amongst "gentlemen in Ayrshire in those

days.

Jan 1

On the evening of the 1st of January, Sir Thomas

Kennedy supped with Sir Thomas Nisbet in the house of the latter at

Maybole. The Lairds of Auchindrain and Dunduff, with a few servants, lay

in wait for him in the yard, and when he came forth to go to his own house

to bed, they fired their pistols at him. ‘He being safe of any hurt

therewith, and perceiving them with their swords most cruelly to pursue

his life was forced for his safety to fly; in which chase they did

approach him so near, as he had undoubtedly been overta’en and killed, if

he had not adventured to run aside and cover himself with the ruins of ane

decayed house; whilk, in respect of the darkness of the night, they did

not perceive; but still followed to his lodging, and searched all the

corners thereof, till the confluence of the people . . . . forced them to

retire.’

For this assault, Sir Thomas Kennedy

pursued at law the Lairds of Auchindrain aud Dunduff, and was so far

successful that Dunduff had to retire into England, while ‘Colzean gat the

house of Auchindrain, and destroyit the . . . . plenishing, and wrackit

all the garden. And also they made mony sets [snares] to have gotten [Auchindrain]

himself; but God preservit him from their tyranny.' Auchindrain, however,

was forced ‘to cover malice by show of repentance, and for satisfaction of

his by-past offence, and gage of his future duty, to offer his

eldest son in marriage to Sir Thomas Kennedy’s dochter; whilk, by

intercession of friends, [was] accepted.’

We shall hear more of this feud

hereafter (see under December 11, 1601).

Feb 17

Under a commission from the king, the provost and bailies of Aberdeen

commenced a series of witch-trials of a remarkable kind. The first

delinquent, Janet Wishart, spouse of John Lees, stabler— a woman

considerably advanced in life—was accused of a great number of maléfices

perpetrated, during upwards of thirty years,

against neighbours, chiefly under a spirit of petty revenge. In the

greater number of cases, the victim was described as being seized with an

ailment under which he passed through the extremes of heat and cold, and

was afflicted with an insatiable drouth. In several cases the illness had

a fatal conclusion. For instance, James Low, stabler, having refused Janet

the loan of his kiln and barn, took a dwining illness in

consequence, ‘melting away like ane burning candle,’ till he died. John,

in his last moments, declared his belief that, if be had lent Janet his

kiln and barn, he would still have been a living man. ‘By the whilk

witchcraft casten upon him, and upon his house, his wife died, his only

son [fell] in the same kind of sickness, and his haill geir, surmounting

three thousand pounds, are altogether wrackit and away.’ It was considered

sufficient proof on this point, that sundry persons testified to having

heard James lay on Janet the blame of his misfortunes. Another person had

been mined in his means, in consequence of his wife obeying a direction of

Janet for the insurance of constant prosperity—namely, taking nine pickles

of wheat and a piece of rowan-tree, and putting them in the four nooks of

the house. Janet had also caused a dozen fowls belonging to a neighbour to

fall from a roost dead at her feet. She raised wind for winnowing some

malt in her own house, at a moment of perfect calm, by putting a piece of

live coal at each of two doors. She caused a neighbour’s cow to give

something like venom instead of milk. A Mart ox which she wished to buy,

became furious; wherefore she got it at her own price, and on her laying

her hands on it, the animal became quiet. There is also a terrible recital

of her causing a neighbour to accompany her to the gallows in the Links,

where she cut pieces from the various members of a dead culprit, to be

used for effecting some of her devilish purposes. This story was only

reported by one who had received it from the woman herself, now deceased;

but it passed as equally good evidence with the rest. It was alleged that,

twenty-two years ago, she had been found sitting in a field of green corn

before sun-rising, when, being asked what she was doing, she said: ‘I have

been peeling the blades of the corn: I find it will be ane dear year; the

blade of the corn grows withershins [contrary to the course of the sun]:

when it grows sungates about [in the direction of the sun’s course], it

will be ane cheap year.’ One of the last points in the dittay was that,

for eight days before her apprehension, ‘continually there was sic ane

fearful rumbling in thy house, that William Murray, cordiner, believit the

house he was into, next to thy house, should have fallen and smoorit him

and his haill bairns.’ This poor woman appears to have been taken to the

stake immediately after her trial. |