|

St John's Dec. 12th 1774.

WE'RE now on land, but my

head is so giddy, that I can't believe I am yet on shore, nor can I

stand more than I did on Shipboard; every thing seems to move in the

same manner it did there. They tell me however, I will get the better of

this in twenty four hours.

My brother came on board

this morning with some Gentlemen, and carried us ashore. Every thing was

as new to me, as if I had been but a day old. We landed on a very fine

Wharf belonging to a Scotch Gentleman, who was with us. We proceeded to

our lodgings thro' a narrow lane; as the Gentleman told us no Ladies

ever walk in this Country. Just as we got into the lane, a number of

pigs run out at a door, and after them a parcel of monkeys. This not a

little surprized me, but I found what I took for monkeys were negro

children, naked as they were born. We now arrived at our lodgings, and

were received by a well behaved woman, who welcomed us, not as the Mrs

of a Hotel, but as the hospitable woman of fashion would the guests she

was happy to see. Her hail or parlour was directly off the Street. Tho'

not fine, it was neat and cool, and the windows all thrown open. A Negro

girl presented us with a glass of what they call Sangarie, [Sangaree was

a tropical drink, known also to the people of the Carolinas. There were

other combinations than that mentioned by Miss Schaw, but the

ingredients were always liquor, water, and spices. Brandy was sometimes

substituted for wine.] which is composed of Madeira, water, sugar and

lime juice, a most refreshing drink. She had with her two Ladies, the

one a good plain looking girl, who I soon discovered was her Niece; but

it was sometime before I could make Out the other. The old Lady [The

"old lady" was Mrs. Dunbar, as was also the doctor's wife. There was no

relationship between them. Dr. John Dunbar (born 1721), member of the

assembly until 1775, graduated at Leyden University in 1742, and

married, in Antigua, Eleanor, daughter of Thomas Watkins, who died

during the hurricane of August 31, 1772. He married again, July 28,

1773, at St. John's, Sarah Warner, daughter of Samuel H. Warner, deputy

provost marshal of the island, a woman much younger than himself, who,

however, died before he did, in 1787. The Dunbar plantation of 16 acres

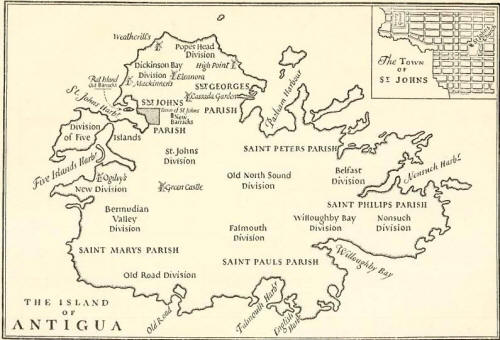

was in the Dickinson Bay division, from which the doctor was returned to

the assembly.] told us, she had been married to a Scotsman, whose memory

was so dear to her, that she loved his whole country. She paid us some

very genteel compliments, and with great seeming sincerity, expressed

the joy it gave her to have us in her house. She was much prepossessed

in my brother's favour, who was now gone out with many of the people in

office. "I know," said she, "every body will love you, and that I will

be able to keep you but a very little while, but I beg that you will let

this be your head quarters, while on the Island." The good Lady said a

great deal, but so much benevolence appeared in every look, that I am

induced to believe her sincere. I shall be sorry if she is not, for I am

already greatly pleased with her.

It was sometime before I

was able to make out who the other Lady was, whom we found with Mrs

Dunbar, for so she is called. The loveliness of her person, her youth

and the modesty of her manners, together with the respect she paid the

Old Lady, made me at first take her for her daughter, but I soon

discovered that her husband was a member of the Council, and that she

waited his return from the Council-board, to carry her to her house, a

few miles up the country. There was something in this young Lady so

engaging, that it is impossible not to wish to know her better. Fanny

and she appeared mutually pleased with each other. At last I fortunately

discovered her to be the wife of my old friend Dr Dunbar, with whom I

had been well acquainted in Scotland, and who had resided many months at

my father's house. We were now much pleased with our Company. Our

Landlady gave us an excellent dinner, at which we had one guest more, a

Capt Blair, [Capt. James Blair may have been an officer of the Royal

American battalion, but his name cannot be found in any of the printed

or manuscript army lists.] a very agreeable genteel young man. My

brother did not return, but our young men made up for the long Lent they

had kept, [The two boys must have found the greater part of the seven

weeks' voyage a veritable Lent.] and Mrs Dunbar is charmed with them. I

believe they have got into good quarters.

Our dinner consisted of many dishes, made

UI) of kid, lamb, poultry, pork and a variety of fishes, all of one

shape, that is flat, of the flounder or turbot kind, but differing from

each other in taste. The meat was well dressed, and tho' they have no

butter but what comes from Ireland or Britain, it was sweet and even

fresh by their cookery. There was no turtle, which she regretted, but

said I would get so much, that I would be surfeited with it. Our desert

was superior to Our dinner, the finest fruits in the 'World being there,

which we had in profusion. During, dinner, our hostess who presided at

the head of her table, (very unlike a British Landlady) gave her hob and

nob, ["Hob and nob" was to drink to the health of the company present.

At many colonial dinners it was the custom for the host to drink a glass

of wine with everyone at the table.] a good grace. I observed the young

Ladies drank nothing but Lime-juice and water. They told me it was all

the women drank in general. Our good landlady strongly advised us not to

follow so bad an example—that Madeira and water would do no body harm,

and that it was owing to their method of living, that they were such

spiritless and indolent creatures. The ladies smiling replied that the

men indeed said so, but it was custom and every body did it in spite of

the advices they were daily getting. What a tyrant is custom in every

part of the world. The poor women, whose spirits must be worn out by

heat and constant perspiration, require no doubt some restorative, yet

as it is not the custom, they will faint under it rather than trangress

this ideal law. I will however follow our good Landlady's advice, and as

I was resolved to shew I was to be a rebel to a custom that did not

appear founded on reason, I pledged her in a bumper of the best Madeira

I ever tasted. Miss Rutherfurd followed my example; the old Lady was

transported with us, and young Mrs Dunbar politely said, that if it was

in the power of wine to give her such spirits, and render her half so

agreeable, she was sorry she had not taken it long ago; but would lose

no more time, and taking up a glass mixed indeed with water, drank to

us. Just as we were

preparing for Tea, my brother, D' Dunbar, Mr Halliday, [The Halliday

family is of old covenanting stock and has figured in the history of

Scotland, county Galloway, since the sixteenth century. John Halliday,

the collector, was born in Antigua, a nephew of William Dunbar and a

son-in-law of Francis Delap, both prominent residents of the island. He

himself had no less than seven plantations in the different divisions,

the two most important of which were "Boons" in St. John's parish and "Weatherills"

near by. He entered the assembly in 1755, resigned in 1757, and was

again returned in 1761. He occupied the position of customs collector

and receiver of the four and a half per cent export duty from 1759 to

1777, an office of importance, as the port of St. John's was much

superior to its only rival in the island, Parham. Of Charles Baird, the

comptroller, we can give no information beyond that which Miss Schaw

furnishes, though his name is to be found in the official list of

customs officials and in Governor Payne's "Answers to Queries."] the

Collector, and Mr Baird, the comptroller, and a very pretty young man

called Martin came to us. Here was a whole company of Scotch people, our

language, our manners, our circle of friends and connections, all the

same. They had a hundred questions to ask in a breath, and my general

acquaintance enabled me to answer them. We were intimates in a moment.

The old Doctor was transported at seeing US, and presently joined his

Lady in a most friendly invitation to stay at his house, which we have

promised to do, as soon as we get our things ashore. The Collector has

made the same request, and we are to be at his country-scat in a day or

two. Mr Halliday is from Galloway, is a man above fifty, but extremely

genteel in his person and most agreeable in his manners; he has a very

great fortune and lives with elegance and taste. His family resides in

Eng- land and he lives the life of a Batchelor. Mr Baird is a near

relation of the Newbeath family, is above sixty, far from handsome, but

appears to be a most excellent creature. I should suppose his connection

had rather been with Mrs Baird, he has so much of her manner, her very

way of speaking. 'Tis my opinion a mutual passion is begun between him

and me, which, as it is not raised on beauty, it is to be hoped will be

lasting. Young Martin, our hostess, who is very frank, tells us, is a

favourite of the Collector's; that he stays always with him, and that it

is supposed he intends to resign in his favour. She moreover informed

us, that M' Martin was much admired by the Ladies, but was very

hardhearted. [Samuel Martin, the "young Martin" here mentioned, was not

a son of Colonel Samuel, though he may have been in some way related to

him. That there was some family connection seems evident from an

agreement entered into in 1775, whereby young Samuel bound himself to

pay annuities to certain members of the Martin family (Oliver, History

of Antigua, II, ç). At this time he may have been twenty or more years

of age, and, as Miss Schaw thought would be the case, he succeeded

Halliday as collector two years later, serving until 1795, when he was

retired. He was followed by Josiah, Colonel Samuel's grandson, who held

the office for half a century. For a woman hater, young Samuel had an

interesting matrimonial career. In 1777, the year ht was appointed

collector, he married Grace Savage, daughter of George Savage of "Savage

Gardens" just outside St. John's, and by her had six children. She died,

aged ço, in i8to, and in 1812 he married again, a widow, name unknown,

by whom he had five children more. Thus he had two wives and eleven

children, which is a little unexpected, in view of Miss Schaw's remarks.

He died soon after 1825, in England, whither he had gone after leaving

the collectorship. Young Martin's plantation in Antigua was called "High

Point" and lay in the northern part of the island, between Winthrop's

Bay and Dutchman's Bay near the entrance to Parham Harbor. He left this

plantation to William, born in i8i6, his second son by his second wife.]

Tea being finished, the Dr and his Lady left us, and we surprised the

Gentlemen, by proposing a walk out of town.

This was at first opposed, but on our

persisting, Mr Baird swore we were the finest creatures he had met these

twenty years. "Zounds," said he, taking my arm under his, "I shall fancy

myself in Scotland." Our walk turned out charmingly, the evening had now

been cooled by the sea breeze, and we were not the least incommoded. We

walked thro' a market place, the principal streets, and passed by a

large church, and thro' a noble burying place. Here we read many Scotch

names, among others, that of poor Jock Trumble [The "Jock Trumble" here

mentioned was probably Lieutenant John Turnbull of the 68th Regiment of

Foot, who died in Antigua, October 9, 1767, and was buried on the

island. The name "Trumbull" is but a corrupted form of the Scottish

"Turnbull," and Scotsmen tell us that the name today is frequently

spelled "Turnbull" and pronounced "Trumbull."] of Curry, who died while

here with his regiment. A little above the town is the new Barracks, a

long large building, in the middle of a field. I do not think its

situation, however, so pretty as that of the old Barracks. A little

beyond that we met a plantation belonging to a Lady, who is just now in

England; from her character I much regret her absence, for by all

accounts, she is the very soul of whim, a much improved copy of Maria

Buchanan, Mrs O, whose stile, you know, I doated on; her house, for she

is a widow, is superb, laid out with groves, gardens and delightful

walks of Tamarind trees, which give the finest shade you can imagine.

[The plantation described is Skerretts alias Nugenes, situated about a

mile along the road past the barracks.]

Here I had an opportunity of seeing and

admiring the Palmetto tree, with which this Lady's house is surrounded,

and entirely guarded by them from the intense heat. They are in general

from forty to sixty feet high before they put Out a branch, and as

straight as a line. If I may compare great things with small, the

branches resemble a fern leaf, but are at least twelve or fifteen feet

long. They go round the boll of the tree and hang down in the form of an

Umbrela; the great stem is white, and the skin like Satin. Above the

branches rises another stem, of about twelve or fourteen feet in height,

coming to a point at the top, from which the cabbage springs, tho' the

pith or heart of the whole is soft and eats well. This stem is the most

beautiful green that you can conceive, and is a fine contrast to the

white one below. The beauty and figure of this tree, however, rather

surprised than pleased me. It had a stiffness in its appearance far from

being so agreeable as the waving branches of our native trees, and I

could not help declaiming that they did not look as if they were of

God's making. We

walked thro' many cane pieces, as they term the fields of Sugar-canes,

and saw different ages of it. This has been a remarkable fine season,

and every body is in fine spirits with the prospect of the Crop of

Sugar. You have no doubt heard that Antigua has no water, ["Antigua has

but one running stream and that is incapable of the least navigation"

(Payne in "Answers to Queries"). Of the water supply the writer of the

Brief Account says, "This island is almost destitute of fresh springs,

therefore the water principally used is rain, which the inhabitants

collect in stone cisterns: this water, after being drawn from the

reservoir, is filtered through a Barbadoes stone, which renders it free

from animalcula, or any disagreeable quality it might have contracted by

being kept in the tank. It is exceedingly soft and well flavored . . .

as good as any I ever tasted in Europe" (pp. 60-61). Governor Payne,

writing to Lord Dartmouth the October before, gives a description of the

island that is equally flattering with that of Miss Schaw. "I have no

disagreeable account of any kind wherewith I am to trouble your

Lordship, from any part of my government. The crops of the present year

which are just finished have in general been very good; and in some of

the islands surpass'd the expectations of the planters; and the present

propitious weather inspires the inhabitants with sanguine hopes of

reaping a plentiful harvest in the ensuing year. There is not in any of

the islands under my command any interruption to the general harmony and

tranquillity which I have the satisfaction of observing to prevail

throughout every part of my government, from my first entrance on my

administration"; and in .January, 1775, he added, "No mischievous sparks

of the continental flame have reached any district of the government.

The trade of every island of it is most uncommonly flourishing.

Provisions of all kinds from the continent of America are cheaper and

more plentiful than they have been in the memory of man" (Public Record

Office, C. 0. 152: 55).] but what falls in rain; A dry season therefore

proves destructive to the crops, as the canes require much moisture.

We returned from our walk, not the least

fatigued, but the Musquetoes [The mosquitoes on the American continent

as well as in the West Indies were a very troublesome novelty to

Europeans. The author of the Brief Account says of Antigua, "The

mosketos are troublesome, but I defend my legs (which is the part these

insects principally attack) with boots" (p. 7). As to the continental

colonies, Boucher complained of mosquitoes in Maryland (Maryland

Magazine, March, 1913, pp. 39-40), Michel in Virginia (Virginia

Magazine, January, 1916, P. 40), and Beverley of the latter colony once

sent for Russian lawn or gauze for four large field beds, "being to let

in the air and keep out mosquitoes and flies" (Beverley Letter Book).

Peck- over, the travelling Quaker preacher, says that he was "taken with

an inflamation in my leg" in New Jersey, "occasioned I think by the

Muskittos biting me. This is a very flat country and very subject to

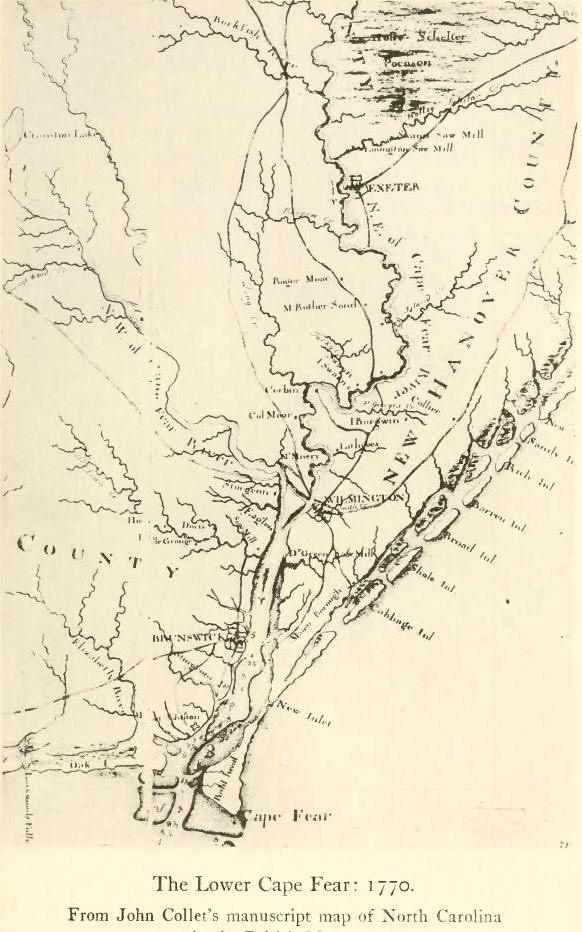

these insects" (Travels). In North Carolina, mosquito nets were included

in inventories and invoices, and in South Carolina in 1744, it was

proposed that the merchants in England send over a large quantity of

Scotch kenting for pavilions, as it would come to a good market, "there

being at present a great demand for that commodity, the inhabitants

being almost devoured by the mosquitos for want thereof:" (South

Carolina Gazette, June 6, 1744). Even the Pilgrims were "much anoyed

with mtiskeetoes," and some of those who returned before 1624 made them

a subject of complaint against the colony. Bradford's History (Ford

ed.), I, 366, and note.] had smelt the blood of a British man, and my

brother has his legs bit sadly. Our petticoats, I suppose, guarded us,

for we have not as yet suffered from these gentry. We supped quite

agreeably, but it was quite in public. No body here is ashamed of what

they, are doing, for all the parlours are directly off the street, and

doors and windows constantly open. I own it appears droll to have people

come and chat in at the windows, while we are at supper, and not only

so, but if they like the parts', they just walk in, take a chair, and

sit down. I considered this as an inconveniency from being in a hotel,

but understand, that every house is on the same easy footing. Every body

in town is on a level as to station, and they are all intimately

acquainted, which may easily account for this general hospitality. The

manner of living too is another reason. They never fail to have a

plentiful table to Sit down to. My friend Baird does not love this

freedom at all, neither does he admit it at his house. Indeed the custom

house people are not considered as on the same footing, and are treated

with more respect. I have now given you my first day in the West Indies,

part of which is from observation, and part from information. I will go

over all the town to morrow, but must now retire and try if I can sleep

at land, tho' I really dread the musquetoes. My brother is gone with the

Collector to sleep.

We have had a sound sleep in an excellent

bed chamber, in which were two beds covered with thin lawn curtains,

which are here called musquetoe nets, but we found it so cool, that we

occupied but one bed. A single very fine Holland sheet was all our

covering, but we found laid by the side of the beds, quilts, in case we

chused them, which by four in the morning we found to be absolutely

necessary. A black girl appeared about seven with a bason of green tea

for each of us, which we drank, and got up to dress, attended by our

swarthy waiting maid, whom we found extremely well qualified for the

office. We now descended into the hail where breakfast was set forth

with every necessary, but were not a little surprised to see a goat

attending to supply us with milk, which she did in great abundance; and

most excellent milk it was. Cream, it is impossible to have, as no

contrivance has yet been fallen on to keep it sweet above an hour. There

are plenty of cows in the Island, but their milk is used only for the

sick, while the goats supply milk for every common purpose, and about

every house are two or three who regularly attend the Tea-kettle of

their own accord.

Our things are now brought ashore by Robt, but Mrs Miller absolutely,

refuses to come to us, which I am not sorry for, as so much ill temper

in a servant would make one look silly, among strangers, and to dispute

the point would render us ridiculous. We have therefore accepted the

proffered service of Memboe, the black girl, before mentioned, for whose

honesty, her Mrshas become responsible, so into her hands we have

commited our Wardrobe.

Breakfast was hardly over, when several

carriages were at the door, begging our acceptance, to carry us about

the town, or where else we chused to go. We accepted one belonging to Mr

Halliday; when Mr Martin placed himself between us, and acted the

character of Gallant with great address. No Lady ever goes without a

gentleman to attend her; their carriages are light and airy; this of Mr

Halliday's was drawn by English horses, which is a very needless piece

of expence; as they have strong horses from New England, and most

beautiful creatures from the Spanish Main. Their Waggons which are large

and heavy, are drawn by Mules, many of which passed Mrs Dunbar's window,

with very thin clothed drivers, nothing on their bodies, and little any

where, which deserves the name of clothing. The women too, I mean the

black women, wear little or no clothing, nothing on their bodies, and

they are hardly prevailed on to wear a petticoat.

In my excursion this day, I met with some

intelligent people, by which means I am become acquainted with a great

many particulars, which my stay would hardly be long enough to have

learned by my own observation. I have had a full view of the town, which

is very neat and very pretty, tho' it still bears the marks of two

terrible Misfortunes: the dreadful fire, and still more dreadful

hurricane. [The fire occurred on August 17, 1769, and consumed

two-thirds of the town, at a loss of £400,000 Antigua currency. The

hurricane occurred on August 31, 1772. Of this terrible disaster

Governor Payne wrote: "On Thursday night, the 27th of August, we had an

exceedingly hard gale of wind, which continued for the space of 7 or 8

hours, and then subsided without doing any material damage. On the night

of Sunday, the 30th of August, the wind blew fresh . . . and continued

increasing till five in the morning when it blew a hurricane from the N.

E. a melancholy darkness prevail'd for more than an hour after sun rise.

At eight o'clock the fury of the tempest in some measure abated, but it

was only to collect new redoubl'd violence, and to display itself, with

tenfold terror, for the space of 4 hours . . Some persons were buried in

the ruins of their houses. Many houses were razed. The doors, windows,

and partitions of the Court House were blown in, the interior completely

wrecked and most valuable papers destroyed. The barracks are in a

deplorable condition. At English Harbour, deemed storm-proof, there was

a squadron under Adm Parry, whose flagship with others drove ashore and

the hospital there was levelled to the ground, crushing in its fall the

unfortunate patients and attendants. My new study, with most of my

papers, was blown away." Quoted in Oliver, History of Antigua, I, cxxi.

There is an old negro adage regarding the coming of hurricanes: "June,

too soon; July, stand by; August, come it must; September, remember;

October, all over."] Many of the streets are not yet repaired, but like

London, I hope it will rise more glorious from its ruins. The publick

buildings are of stone, and very handsome, they have all been built at a

great expence, since the hurricane, which happened later, and was

attended with more general devastation than the fire. The houses built

immediately after this calamity bear all the marks of that fear, which

possessed the minds of the Inhabitants at the time. They are low and

seem to crutch [crouch], as if afraid of a second misfortune. But by

degrees they have come to the same standard as formerly. The town

consists of sixteen streets, which all ly to the trade wind in full view

of the bay. The

Negroes are the only market people. No body else dreams of selling

provisions. Thursday is a market day, but Sunday is the grand day, as

then they are all at liberty to work for themselves, and people hire

workmen at a much easier rate, than on week days from their Masters. The

Negroes also keep the poultry, and it is them that raise the fruits and

vegetables. But as I am not yet in the country, I cannot give you so

good an account, as I shall do when I have seen a Negro town. We dine

this day in town, and to morrow go to Dr Dunbar's. We are much

disappointed to find that Sir Ralph Payn [Sir Ralph Payne, governor of

the Leeward Islands, with residence in Antigua, was born in St.

Christopher, in 1739. He was commissioned governor May 10. 1771,

resigned February 17, 1775, and returned soon after to England. "Hardly

any West Indian governor," says the author of the Brief Account, "ever

acquired credit there except Sir George Thomas and Sir Ralph Payne.

These men were both native West Indians, who knew the dis. position of

the people they had to govern, and by prudently keeping the arrogant at

as great a distance, as the more modest would naturally keep themselves,

they had the good fortune to he approved" (p. 166). Lord Dartmouth said

that Sir Ralph had "ever shown a zeal and activity that is highly

pleasing to the king"; and in August, 1775, after he had left the island

and another appointee was under consideration, the general assembly of

Antigua presented an address to the king, expressing their gratitude for

his having sent them a man of Sir Ralph's character and worth and

begging that he would send him back to them again. Governor Payne had a

career in England also. He was an M.P. for Plymouth in 1762, Shaftesbury,

1769, and Camelford, 1774. He was made a K.B. in 1771, and on October 1,

1795, was created an Irish peer, Baron Lavington of Lavington, entering

the Privy Council in 1799. He was reappointed governor of Antigua,

January 20, 1799, and died in the island, August 3, 1807, aged 68. ] and

his Lady are not on the Island, but they are expected to be here by

Christmas, as Lady Payn never misses her duty. She has a most amiable

character, and is the idol of the whole people. I regret much not having

the happiness to see her, as we are particularly recommended to the

governor-general and her Ladyship by Lord Mansfield. [The Right

Honorable William Lord Mansfield was the fourth son of David Murray,

Viscount Stormont, and brother of the Mrs. Murray of Stormont mentioned

later in the narrative (p. 247). He was horn at Scone, educated at

Perth, and formed part of that Scottish circle of intimates in which

Miss Schaw moved. He is frequently referred to, here and elsewhere, as

giving assistance of one kind or another to his Scottish friends. His

judicial and parliamentary career is too well known to need Comment.]

We have just had a visit from two Ladies,

Mrs Mackinon and her daughter. [Mrs. Mackinnen was Louise Vernon of

Hilton Park, Stafford, who had married William Mackinnen of Antigua in

1757. Mackinnen was an absentee planter for many years, but returned to

the island in 1773, and became a member of the council. He went hack to

England some time before 1798, lived at Exeter, and died in 1809. He was

buried at Binfield, Berks, where he had a residence. In Antigua, he had

two plantations, "Golden Grove" and "Mackinnen's." the latter, an estate

of 830 acres in St. John's parish, is probably the one visited by Miss

Schaw. There were four daughters.] They are two of the most agreeable

people I ever saw. We had letters for them, which they no sooner

received, than they came to invite us to their house. Mrs Mackinon is an

English Lady and but very lately come out; she was much pleased at

meeting with some British people. We are engaged to pass some of our

time with them: We go to church on Sunday, which they tell us is a very

fine one, and dine afterwards with Collector Halliday. I must bid you

Adieu for the present; my next Letter will be from the Country.

The Eleanora

[Dr. Dunbar's plantation, "Eleanora," lay about two miles north of St.

John's, a mile farther on than that of William Mackinnen. Both were in

the Dickinson Bay division.]

I have heard or read of a painter or poet, I

forget which, that when he intended to excell in a Work of Genius, made

throw around him everything most pleasing to the eye, or delightful to

the senses. Should this always hold good, at present you might expect

the most delightful epistle you ever read in your life, as whatever can

charm the senses or delight the Imagination is now in my view.

My bed-chamber, to render it more airy, has

a door which opens into a parterre of flowers, that glow with colours,

which only, the western sun is able to raise into such richness, while

every breeze is fragrant with perfumes that mock the poor imitations to

be produced by art. This parterre is surrounded by a hedge of

Pomegranate, which is now loaded both with fruit and blossom; for here

the spring does not give place to Summer, nor Summer to Autumn; these

three Seasons are eternally to be found united, while we give up every

claim to winter, and leave it entirely to you.

This place which belongs to my friend Doctor

Dunbar, is not above two or three miles from town, and as it is an easy

ascent all the way, stands high enough to give a full prospect of the

bay, the shipping, the town and many rich plantations, as also the old

Barracks, the fort and the Island I before mentioned. Indeed it is

almost impossible to conceive so much beauty and riches under the eve in

one moment. The fields all the way down to the town, are divided into

cane pieces by hedges of different kinds. The favourite seems the

log-wood, which, tho' extremely beautiful, is not near so fit for the

purpose, as what is called the prickly pear, which grows into a fence as

prickly and close as our hawthorn; but so violent is the taste for

beauty and scent, that this useful plant is never used, but in distant

plantations. I am however resolved to enter into no particulars of this

kind, till I recover my senses sufficiently to do it coolly; for at

present, the beauty, the novelty, the ten thousand charms that this

Scene presents to me, confuse my ideas. It appears a delightful vision,

a fairy Scene or a peep into Elysium; and surely the first poets that

painted those retreats of the blessed and good, must have made some West

India Island sit for the picture.

Tho' the Eleanora is still most beautiful,

yet it bears evident marks of the hurricane. A very fine house was

thrown to the ground, the Palmettoes stand shattered monuments of that

fatal calamity; with these the house was surrounded in the same manner,

as I described the plantation near town. Every body has some tragical

history to give of that night of horror, but none more than the poor

Doctor. His house was laid in ruins, his canes burnt up by the

lightening, his orange orchyards, Tammerand Walks and Cocoa trees torn

from the roots, his sugar works, mills and cattle all destroyed; yet a

circumstance was joined, that rendered every thing else a thousand times

more dreadful. It happened in a moment a much loved wife was expiring in

his arms, and she did breath her last amidst this War of Elements, this

wreck of nature; while he in vain carried her from place to place for

Shelter. This was the Lady I had known in Scotland. The hills behind the

house are high and often craggy, on which sheep and goats feed, a Scene

that gives us no small pleasure, and even relieves the eye when fatigued

with looking on the dazzling lustre the other prospect presents you.

I have so many places to go to, that I fear

I will not have time to write again, while on this Island. My brother

proposes to make a tour round all the Islands, in which we will bear him

company. My brother

has gone to make the tour of the Islands with- out us. Every body was so

desirous of our staying here, and we were so happy, that we easily

agreed to their obliging request, nor have we reason to repent our

compliance, as every hour is rendered agreeable by new marks of

civility, kindness and hospitality. Miss Rutherfurd has found several of

her boarding school-friends here; [It is of course impossible to

identify Fanny's boarding school, but the following entry in the Scots

Magazine (36, p. 392) may well refer to it. "Miss Sarah Young, daughter

of Patrick Young of Killicanty, [who] kept a boarding school in

Edinburgh for young ladies upwards of thirty years," died on July 30,

1774.] they have many friends to talk of, many scenes to recollect. This

shows me how improper it is in the parents to send them early from them-

selves and their country. They form their Sentiments in Britain, their

early connections commence there, and they leave it just when they are

at the age to enjoy it most, and return to their friends and country, as

banished exiles; nor can any future connection cure them of the longing

they have to return to Britain. Of this I see instances every day, and

must attribute to that cause the numbers that leave this little

paradise, and throw away vast sums of money in London, where they arc,

either entirely overlooked or ridiculed for an extravagance, which after

all does not even raise them to a level with hundreds around them; while

they neglect the cultivation of their plantations, and leave their

delightful dwellings to Overseers, who enrich themselves, and live like

princes at the expence of their thoughtless masters, feasting every day

on delicacies, which the utmost extent of expence is unable to procure

in Britain. Antigun has more proprietors on it however than any of the

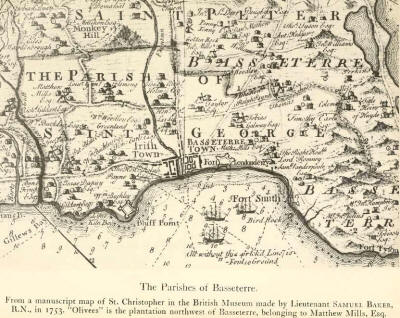

other Islands, which gives it a great Superiority. St Christopher's,

they tell me, is almost abandoned to Overseers and managers, owing to

the amazing fortunes that belong to Individuals, who almost all reside

in England. Mr Mackinnon had never been out here, had not his overseer

forgot he had any superior, and having occasion for the whole income,

had sent his Master no remittances for above two years. He found things

however in very good order, as this gentleman for his own sake, had

taken care of that. But as his constitution is now entirely British, he

feels the effects of the Climate, and is forced to think of wintering at

New York for his health. We have seen every body of fashion in the

Island, and our toilet is loaded with cards of Invitation, which I hope

we will have time to accept, and I will then be able to say more as to

the manners of a people with whom I am hitherto delighted. Forgive me,

dearest of friends, for being happy when so far from you, but the hopes

of meeting, to be happy hereafter supports my spirits.

I was yesterday at church, [St. John's

Church was built in the years 1740-1745, the tower, which had not been

erected when Miss Schaw visited the island, being added in 1786. 1789.

The building occupied a conspicuous position on an eminence in the

northeast quarter of the town and was visible from all the country

round. It was built of brick and stone, its yard being enclosed by a

brick wall, the bricks having been obtained in England and America. On

pillars at the south entrance were two well executed figures in Portland

stone of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist, to whom the

church was dedicated, and in the tower were a clock and a bell given in

1789 by John Delap Halliday, son of the collector. The organ had been

purchased in 1760 and in 1772 an organist, George Harland Hartley, was

installed. The rector, whom Miss Schaw so much disliked, was the Rev.

John Bowen, 1767.1783 (Oliver, III, 357-359; Brief Account, p. 21).] and

found they had not said more of it than it deserved; for tho' the

outside is a plain building, its inside is magnificent. It has a very

fine organ, a spacious altar, and every thing necessary to a church

which performs the English Service. You know I am no bigoted

Presbyterian, and as the tenets are the same, I was resolved to conform

to the ceremonies, but am sorry to find in myself the force of habit too

strong, I fear, to be removed. The church was very full, the Audience

most devout. I looked at them with pleasure, but found I was a mere

Spectator, and that what I now felt had no more to do with me, than when

I admired Digges [For Digges, see below, p. 136.] worshipping in the

Temple of the Sun. This is a discovery I am sorry to make, but if one

considers that the last Clergyman I heard in Scotland was Mr Webster,

[Rev. Dr. Alexander Webster (1707.1784) was chaplain in ordinary for

Scotland in 1771 and a dean of the royal chapel. His son, Lieutenant

Colonel William Webster, served in the British army in America and was

wounded at Guilford Court House. Later he died of his wounds and was

buried at Elizabeth, Bladen county, North Carolina.] and that the last

service I heard him Perform was that of a prayer for myself and friends,

who were biddinp adieu to their native land, in which were exerted all

those powers, which he possesses in so eminent a degree, his own heart

affected by the subject, and mine deeply, deeply interested. It was no

wonder that those now read from a book by a Clerk, who only did it,

because he was paid for doing it, appeared cold and unapropos. The

musick tho' fine added as little to my devotion as the sniveling of a

sincere-hearted country precentor, perhaps less; but the beauty, the

neatness and elegance of the Church pleased me much, and in this I own,

we are very defective in Scotland. The seat for the Governor General is

noble and magnificent, covered with Crimson velvet; the drapery round it

edged with deep gold fringe; the Crown Cyphers and emblems of his office

embossed and very rich. Below this is the seat for the Counsellors

equally fine and ornamented, but what pleased me more than all I saw,

was a great number of Negroes who occupied the Area, and went thro' the

Service with seriousness and devotion. I must not forget one thing that

really diverted me; the parson who has a fine income is as complete a

Coxcomb as I ever met with in a pulpit. He no sooner cast his eyes to

where we were than he seemed to forget the rest of the Audience, and on

running over his sermon, which he held in his hand, he appeared

dissatisfied, and without more ado dismounted from the pulpit, leaving

the Service unfinished, and went home for another; which to do it

justice was a very good one.

We found Mr Martin at the Church door with

our carriages, into which we mounted, and were soon at Mr Halliday's

Plantation, where he this day dined; for he has no less than five, all

of which have houses on them. This house is extremely pleasant, and so

cool that one might forget they were under the Tropick. We had a family

dinner, which in England might figure away in a newspaper, had it been

given by a Lord Mayor, or the first Duke in the kingdom. Why should we

blame these people for their luxury? since nature holds out her lap,

filled with every thing that is in her power to bestow, it were sinful

in them not to be luxurious. I have now seen Turtle almost every day,

and tho' I never could eat it at home, am vastly fond of it here, where

it is indeed a very different thing. You get nothing but old ones there,

the chickens being unable to stand the voyage; even these are starved,

or at best fed on coarse and improper food. Here they are young, tender,

fresh from the water, where they feed as delicately, and are as great

Epicures, as those who feed on them. They laugh at us for the racket we

make to have it divided into different dishes. They never make but two,

the soup and the shell. The first is commonly made of old Turtle, which

is cut up and sold at Market, as we do butcher meat. It was remarkably

well dressed to day. The shell indeed is a noble dish, as it contains

all the fine parts of the Turtle baked within its own body; here is the

green fat, not the slabbery thing my stomach used to stand at, but firm

and more delicate than it is possible to describe. Could an Alderman of

true taste conceive the difference between it here and in the city, he

would make the Voyage on purpose, and I fancy he would make a voyage

into the other world before he left the table.

The method of placing the meal is in three

rows the length of the table; six dishes in a row, I observe, is the

common number. On the head of the centre row, stands the turtle soup,

and at the bottom of the same line the shell. The rest of the middle row

is generally made of fishes of various kinds, all exquisite. The King

fish is that most prized; it resembles our Salmon, only the flesh is

white. The Crouper is a fish they much esteem, its look is that of a

pike, but in taste far superior. The Mullets are vastly good. These

three I think are what they principally admire, but there are others

that also make up the table. The Snapper cats like a kind of Turbot, not

less delicate than what ye have. They named thirteen different fishes

all good, many of which I have cat and found so. They are generally

dressed with rich sauces; the red pepper is much used, and a little pod

laid by every plate, as also a lime which is very necessary to the

digesting the rich meats. The lime, I think, is an addition to every

dish. The two side

rows are made up of vast varieties: Guinea fowl, Turkey, Pigeons,

Mutton, fricassees of different kinds intermixed with the finest

Vegetables in the world, as also pickles of every thing the Island

produces. By the bye, the cole mutton is as fine as any I ever eat. It

is small, the grain remarkably fine, sweet and juicy, and what you will

think wonderful is, that it is thus good, tho' it is eat an hour after

it is killed. The beef I do not think equal to the Mutton; it comes

generally from New England, and I fancy is hurt by the Voyage. They have

just now a scheme of raising it on the high plantations, several of

which have begun to wear out, from the constant crops of sugar that have

been taken from them. The second course contains as many dishes as the

first, but are made up of pastry, puddings, jellys, preserved fruits,

etc. I observe they bring the Palmetto cabbage to both courses, in

different forms. Of this they are vastly fond, and give it as one of

their greatest delicacies. Indeed I think it one of the most expensive,

since to procure it, they must ruin the tree that bears it, and by that

means deprive themselves of at least some part of that shade, for which

they have so much occasion.

I will finish the table in this letter, for

tho' I like to see it, yet I hope to find twenty things more agreeable

for the Subject of my future letters; yet this will amuse some of our

eating friends. The pastry is remarkably fine, their tarts are of

various fruits, but the best I ever tasted is a sorrel, which when baked

becomes the most beautiful Scarlet, and the sirup round it quite

transparent. The cheese-cakes are made from the nut of the Cocoa. The

puddings are so various, that it is impossible to name them: they are

all rich, but what a little surprised me was to be told, that the ground

of them all is composed of Oat meal, of which they gave me the receipt.

They have many, dishes that with us are made of milk, but as they have

not that article in plenty, they must have something with which they

supply its place, for they have sillabubs, floating Islands, etc. as

frequently as with you. They wash and change napkins between the

Courses. The desert now comes under our observation, which is indeed

something beyond you. At Mr Halliday's we had thirty two different

fruits, which tho' we had many other things, certainly was the grand

part, yet in the midst of this variety the Pine apple and Orange still

keep their ground and are preferred. The pine is large, its colour deep,

and its flavour incomparably fine, yet after all I do not think it is

superior to what we raise in our hot houses, which tho' smaller are not

much behind in taste even with the best I have seen here, tho' in size

and beauty there is no comparison. As to the Orange it is quite another

fruit than ever I tasted before, the perfume is exquisite, the taste

delicious, it has a juice which would produce Sugar. The Shaddack is a

beautiful fruit, it is generally about four or five pounds weight, its

Rind resembles an Orange, yet I hardly take it to be of the same tribe,

as neither the pulp nor seed lies in the same manner. There are two

kinds, the white and the purple pulp, the last is best. There is another

fruit as large as a Shaddack, but which is really an Orange; this is

called the forbidden fruit, and looks very beautiful, tho' I do not

think it tastes so high as the Orange. The next to these is the

Allegator pear, a most delicious fruit; then come in twenty others of

less note, tho' all good and most refreshing in this climate. The

Granadila is in size about the bigness of an egg, its colour is bright

yellow, but in seeds, juice and taste, it exactly resembles our large

red gooseberry; it is eat with a tea spoon; they say it is the coolest

and best thing they can give in fevers. ["Forbidden fruit" is a small

variety of shaddock, so called because it is supposed to resemble the

forbidden fruit of the Garden of Eden. The granadilla is the fruit of a

species of passion flower (Passiflora quadrangularis), often six to

eight inches in diameter. Miss Schaw anticipates the modern liking for

the alligator pear.] The grapes are very good, the melons of various

kinds as with you, but it were endless to name them; every thing bears

fruit or flowers or both.

They have a most agreeable forenoon drink,

they call Beveridge, which is made from the water of the Cocoa nut,

fresh lime juice and sirup from the boiler, which tho' sweet has still

the flavour of the cane. This the men mix with a small proportion of

rum; the Ladies never do. This is presented in a crystal cup, with a

cover which some have of Silver. Along with this is brought baskets of

fruit, and you may eat as much as you please of it, because (according

to their maxim) fruit can never hurt. I am sure it never hurts me. When

I first came here, I could not bear to see so much of a pine apple

thrown away. They cut off a deep pairing, then [cut] out the firm part

of the heart, which takes away not much less than the half of the apple.

But only observe how easy it is to become extravagant. I can now feel if

the least bit of rind remains; and as to the heart, heavens! who could

eat the nasty heart of a pine apple. I shall only mention the Guava,

which is a fruit I am not fond of as such, but makes the finest Jelly I

ever saw. This with Marmalade of pine apple is part of Breakfast, which

here as well as in Scotland is really a meal.

They have various breads, ham, eggs, and

indeed what you please, but the best breakfast bread is the Casada

cakes, [The cassada or cassava is a fleshy root, the sweet variety of

which is still used for food. The writer of the Brief Account gives

nearly the same list of fruits as does Miss Schaw, and of the cassava

says, "Cassava (commonly called Cassada) is a species of bread made from

the root of a plant of the same name, by expression. The water, or

juice, is poisonous, but the remaining part after being dried, or baked

on thick iron plates, is both wholesome and palatable, it is eaten dry

or toasted, and it also makes excellent puddings" (p. 63; cf. 64-67,

68-72). The Antigua plantation of Abraham Redwood, of Rhode Island, who

founded the Redwood Library at Newport, was called "Cassada Garden." It

was in St. George's parish.] which they send up buttered. These are made

from a root which is said to be poison. Before it goes thro' the various

operations of drying, pounding and baking, you would think one would not

be very clear as to a food that had so lately been of so pernicious a

nature, yet such are the effects of Example, that I eat it, not only

without fear, but with pleasure. They drink only green Tea and that

remarkably fine; their Coffee and chocolate too are uncommonly good;

their sugar is monstrously dear, never under three shillings per pound.

At this you will not wonder when you are told, they use none but what

returns from England double refined, and has gone thro' all the duties.

I believe this they are forced to by act of parliament, but am not

certain. [There was no act of parliament forbidding sugar-refining in

the West Indies, but the British refiners objected strongly to the West

Indian planters' entering into competition with themselves (since under

the mercantilist scheme they should send to England only raw materials)

and endeavored to discourage it in every way possible. Sugar-refining

was deemed a form of manufacturing, in which the colonists were not

expected to engage. Generally speaking, treatment in the West Indies of

the raw juice of the sugar cane went no farther than the Muscovado

process, which produced the various grades of brown sugar, with the

by-product, molasses. For a description of this process, see Aspinall,

British West Indies, pp. 171.172; Jones and Scard, The Manufacture of

Cane Sugar; and for a contemporary illustration of a sugar mill,

Universal Magazine, II, 103. This process is still continued on man)'

West Indian estates, as it is much cheaper than the vacuum process and

furnishes the market not only with molasses, but also with the old brown

sugar, "sweetest of all and the delight of children for their bread and

butter."] This however is a piece of great extravagance, because the

sugar here can be refined into the most transparent sirup and tastes

fully as well as the double refined Sugar, and is certainly much more

wholesome. Many of the Ladies use it for the Coffee and all for the

punch. The drink which I have seen every where is Punch, Madeira, Port

and Claret; in sonic places, particularly at Mr Halliday's, they have

also Burgundy. Bristol beer and porter you constantly find, but they

have not yet been able to have Champaign, as the heat makes it fly too

much. They have cyder from America very good. I forgot to tell you that

along with the desert come perfumed waters in little bottles, also a

number of flowers stuck into gourds. One would think that this letter

was wrote by a perfect Epicure, yet that you know is not the case, but

this is the last time I shall mention the table, except in general,

unless I find some very remarkable difference between this and the other

Islands I may be in.

I have been on a tour almost from one end of

the Island to the other, and am more and more pleased with its beauties,

as every excursion affords new objects worthy of notice. We have been on

several visits, particularly to Coil. Martin, but I will say nothing of

him till I bring you to his house. He is an acquaintance well worth your

making, and I will intro- duce him to you then in form. As we were to

make a journey, we set early off, and for some hours before the heat,

had a charming ride thro' many rich and noble plantations, several of

which belonged to Scotch proprietors, particularly that of the

Dillidaffs (Lady Oglivy and Mr Leslie). ["Dillidaff" is probably

phonetic for Tullideph, a well-known Scottish name. Dr. Walter Tullideph

of Antigua had two daughters. Charlotte, who married Sir John Ogilvy,

and Mary, who married Hon. Col. Alexander Leslie. After leaving St.

John's the party rode southward along the coast, turning eastward a mile

or so to visit "Green Castle," Colonel Martin's estate in Bermudian

Valley under Windmill Hill.] We soon arrived at that of Mr Freeman.

[Arthur Freeman was the eldest son and the heir-at-law of Thomas Freeman

(died, 1736). He was born in 1724 and died January 30, 1780, aged 6. In

1765, when forty-one years old, he eloped with the youngest daughter of

the governor, George Thomas, and went to England. Governor Thomas, a

native of Antigua and deputy governor of Pennsylvania for nine years,

had been appointed governor of the Leeward Islands in 1753. He retired

in 1766, was made a baronet in the same year, and died in London,

December 31, 1773, aged 79. He was so angry with Freeman for running off

with his daughter, at that time but nineteen years old, that he

suspended him from the council, giving the following elaborate statement

of reasons. "In defiance of the laws of Great Britain and of this

Island, in contempt of the respect due to him as his Majesty's Governor

in Chief of the Leeward Islands, and in violation of the laws of

hospitality [Freeman] basely and treacherously seduced his daughter, of

considerable pretensions, from the duty and obedience due to him as a

most affectionate tender father, by prevailing on her to make a private

elopement from his house, with assurances, from his uncommon indulgence,

of an easy forgiveness and by bribing an indigent Scotch parson, who had

been indebted to the general [Thomas] for his daily bread, to join them

in marriage without licence or any other lawful authority, in hopes of

repairing the said Freeman's fortune, become desperate by a series of

folly and extravagance" (Oliver, I, 266). The Privy Council in England,

deeming the matter a private one, refused to support the action of the

choleric old governor and restored Freeman to the council. He returned

and took his seat in 1770. Apparently he left his wife in England, where

she died in 1797, aged 52, for Miss Schaw's account contains no hint of

a wife. He must have gone back later, for he was buried in Willingdon

Church, Sussex. For an intimate picture of Governor Thomas in

Pennsylvania in 1744, see Hamilton's Itinerarium (privately printed,

1907), pp. 25, 33, 35.] This Gentleman who is remarkable for his

learning, is no stranger to the polite Arts, and tho' not a martyr, is a

votary to the Graces, as appears by every thing round him. His

plantation, which is laid Out with the greatest taste, has a mixture of

the Indian and European. If your eye is hurt by the stiff uniformity of

the tall Palmetto, it is instantly relieved by the waving branches of

the spreading Tammerand, or the Sand-box tree. The flowering cyder is a

beautiful tree, covered with flowers, and along Mr Freeman's avenue

these were alternately intermixed with Orange trees, limes, Cocoa Nuts,

Palmettoes, Myrtles and citrons, with many more which afforded a most

delightful shade, which continued till we arrived at the bottom of a

green hill, on which the house stands.

This hill was also shaded with trees,

beneath which grow flowers of every hue, that the western sun is able to

paint. Amongst these I saw many that with much pains are raised in our

hot houses; but how inferior to what they are here, in their native

soil, without any trouble, but that of preventing their overgrowing each

other. For as they are the weeds of this country, like other weeds they

wax fast. The Carnation tree, or as they call it the doble day is a most

glorious Plant; it does not grow above ten feet high, so can only be

numbered amongst Shrubs, but is indeed a superior one even here. The

leaf is dark green, the flowers bear an exact resemblance to our largest

Dutch Carnation, which hang in large bunches from the branches. The

colours are sometimes dark rich Crimson spotted or specked with white,

sometimes purple in the same manner. Ruby colour is the lightest I

observed. They are often one colour, and when that is the case, they are

hardly to be looked at while the sun shines on them. These you meet

every where. Another is the passion flower, which grows in every hedge

and twines round every tree; it here bears a very fine fruit, and as I

formerly observed, the three seasons of Spring, Summer and Autumn go

hand in hand. The fruit and flower ornament the bush jointly. There is

another beautiful shrub, which they call the four o'clock, because it

opens at four every afternoon; this is absolutely a convulvalous, and

they have both the major and minor. The blue is the finest Velvet and

the Crimson the brightest satin; but allowing for the superiority of

colour produced by the warmth of a Tropick sun, I saw no other

difference, and on this discovery I found Out that many more of the

plants were of the same tribes at least with what we have, but so

greatly improved, that they were hardly to be known. How different is

that from the plants of this country, when they come to our Northern

Climate. My seeing

all these in high perfection at Mr Freeman's plantation led me to

describe them here, tho' every place is full of them; and they are a

great hurt to the Canes, tho' when taken in as he has them, they are

most beautiful. His house, which stands on the Summit of this little

hill, is extremely handsome, built of stone. I forgot to tell you that

every house has a handsome piazza; that to his is large and spacious.

You reach the house by a Serpentine walk, on each side grows a hedge of

Cape Jasmine. The verdure which appeared here is surprising, and shews

that it only requires a little care to exclude that heat which ruins

every thing. The sun was now high, vet it was so cool, that we were able

to walk a great way under these trees. I am sorry to add, that I fear

the esteemable master is not long to enjoy this earthly paradise. He has

been close confined for many months with an illness in his head; one of

his eyes is already lost, and it is dreaded, that tho' he were to

recover his health, he would be deprived of the pleasure of viewing

these beauties I have so much admired. My Brother was often with him and

vastly fond of him.

We were next at the plantation of a Mr

Malcolm, [Patrick Malcolm was a surgeon of Antigua, who died in 1785. He

had a diploma from Surgeons Hall, London, as had Dr. Dunbar, and was

licensed to practice in the island in 1749. That he was on terms of

close intimacy with the Martins appears from the mention of his name

several times in their wills. His relationship to the Rutherfurds we

have not been able to discover. He may have been a brother of George

Malcolm of Burnfoot in Dumfriesshire, who married Margaret, daughter of

.James Paisley of Craig and Burn near Langholm, and so have been

connected with the Paisleys of Lisbon (below, P. 214).] a near relation

of Mr Rutherfurd's. This Gentleman was bred a physician, but has left

off practice, and enjoys a comfortable estate in peace and quiet,

without wife or children. But it is inconceivable how fond he was of

these relations, whom he caressed as his children, loading them with

every thing he had that was good. I shall say nothing of many other

places, as I long to bring you acquainted with the most delightful

character I have ever yet met with, that of Coll. Martin, [See Appendix

II, 'The Martin Family."] the loved and revered father of Antigua, to

whom it owes a thousand advantages, and whose age is yet daily employed

to render it more improved and happy. This is one of the oldest families

on the Island, has for many generations enjoyed great power and riches,

of which they have made the best use, living on their Estates, which are

cultivated to the height by a large troop of healthy Negroes, who

cheerfully perform the labour imposed on them by a kind and beneficent

Master, not a harsh and unreasonable Tyrant. Well fed, well supported,

they appear the subjects of a good prince, not the slaves of a planter.

The effect of this kindness is a daily increase of riches by the slaves

born to him on his own plantation. He told me he had not bought in a

slave for upwards of twenty years, and that he had the morning of our

arrival got the return of the state of his plantations, on which there

then were no less than fifty two wenches who were pregnant. These

slaves, born on the spot and used to the Climate, are by far the most

valuable, and seldom take these disorders, by which such numbers are

lost that many hundreds are forced yearly to be brought into the Island.

[In his Essay upon Plantership, PP. 2-7, Colonel Martin deals at length

with the proper care of plantation negroes, and expresses opinions

similar to those ascribed to him by Miss Schaw.]

On our arrival we found the venerable man

seated in his piazza to receive us; he held out his hands to us, having

lost the power of his legs, and embracing us with the embraces of a fond

father, "You are welcome," said he, "to little Antigua, and most

heartily welcome to me. My habitation has not looked so gay this long

time." Then turning to Mr Halliday who had brought us his invitation,

"Flow shall I thank you, my good friend," said he, "for procuring me

this happiness, in persuading these ladies to come to an old man. 01(1,

did I say? I retract the word: Eighty five that can be sensible of

beauty, is as young as twenty five that can be no more." There was

gallantry for you. We now had fruit, sangarie and beverage brought us,

not by slaves; it is a maxim of his that no slave can render that

acceptable Service he wishes from those immediately about himself; and

for that reason has made them free, and the alacrity with which they

serve him, and the love they bear him, shew he is not wrong. His table

was well served in every thing; good order and cheerfulness reigned in

his house. You would have thought the servants were inspired with an

instinctive knowledge of your wishes, for you had scarcely occasion to

ask them. His conversation was pleasant, entertaining and instructive,

his manners not merely polite but amiable in a high degree. It was

impossible not to love him. I never resisted it; but gave him my heart

without hesitation, for which I hope you will not blame me, nor was

Fanny less taken than myself with this charming old man.

He told us that in compliance with the

wishes of his children, he had resided in England for several years,

"but tho' they kept me in a greenhouse," said he, "and took every method

to defend me from the cold, I was so absolute an exotick, that all could

not do, and I found myself daily giving way, amidst all their tenderness

and care; and had I stayed much longer," continued he, smiling, "I had

actually by this time become an old man. I have had, Madam," said he

turning to me, "twenty three children, and tho' but a small number

remain, they are such as may raise the pride of any father. One of my

sons you will know if you go to Carolina, he is governor there; another,

my eldest, you know by character at least." [The son in Carolina was

Governor Josiah Martin; the one in England, whose character Miss Schaw

knew, was Samuel Martin, Josiah's half-brother, who attained wide

notoriety from his duel with John Wilkes.] This I did and much admired

that character. He wishes to have his dear little Antigua independent;

he regrets the many Articles she is forced to trust to foreign aid, and

the patriot is even now setting an example, and by turning many of the

plantations into grass, he allows them to rest and recover the strength

they have lost, by too many crops of sugar, and by this means is able to

rear cattle which he has done with great success. [Colonel Martin was

one of those who foresaw the eventual decay of the industry of the

island, because of its cultivation, to the exclusion of everything else,

of the single staple, sugar. He wished to see some of the cane land

converted into pasture for the rearing of sheep and cattle.] I never saw

finer cows, nor more thriving calves, than I saw feeding in his lawns,

and his waggons are already drawn by oxen of his own rearing.

We were happy and delighted with every thing

while there, but as we prepared to leave him, found we had a task we

were not aware of; for during the time we stayed, he had formed a design

not to part with us. This he had communicated to Mr Halliday and young

Martin, who were much pleased with it, as they were so good as to wish

to retain us, if possible, on the Island. I shall never forget with what

engaging sweetness the dear old man made the proposal, why did he not

make another, that would have rendered him master of our fate, of which

we ourselves had not the disposal. "You must not leave me," said he,

taking both our hands in his, "every thing in my power shall be

subservient to your happiness; my age leaves no fear of reputation."

"You," said he to me, "shall be my friend, my companion, you shall grace

my table and be its mistress; and you," continued he turning to Miss

Rutherfurd, "You, my lovely Fanny, shall be my child, my little

darling." "I once," said he, with a sigh, "had an Angel Fanny of my own,

she is no more, supply her place." Nits Dunbar joined and begged as if

her life had depended on our compliance. "Stay," said the Coll:, "at

least till Mr S. be settled, ["Till Mr. Schaw be settled," that is, till

Alexander Schaw be definitely established in his Post as searcher of

customs at St. Christopher.] the will then come for you." It was in

vain, go we must, and go we did, tho' my heart felt a pang like that

which it sustained when I lost the best of fathers. [Gideon Schaw of

Lauriston, the father of Janet and Alexander, died January 19, 1772

(Scots Magazine, 34, P. When he was born we do not know, but he was

already married in 1726, for Patrick Walker, in his Biographia

Presbyterinna (II, 283-284), tells a grewsome tale of the execution and

burial near Lauriston at that time of certain condemned persons, in

connection with which he mentions both Gideon Schaw and his wife. In

1730 Gideon (or Gidjun) was appointed supervisor of the salt-duty at

AIloa, the leading customs port at the head of the Firth of Forth, and

there remained until 1734, when he removed to a similar post at

Prestonpans, a smaller town below Leith. There he continued to live

until 1738, when he was appointed collector of customs at Perth, at the

head of the Firth of Tay, serving in that capacity until 1751, when he

became assistant to Harnage, the register-general of tobacco in

Scotland, with the title of assistant in Scotland to the

register-general in England. His appointment was renewed in 1761 (on the

accession of George lII) and he continued to serve until his death in

1772, residing in Lauriston. His salary, beginning at £30 a year, rose

to £150 at the end, an amount not large even for those days. Miss Schaw

in her journal frequently refers to Perth, the Tay, and the country

about.]

Last Saturday was

Christmass which we had engaged to pass with Mr Halliday, but our good

old hostess Mrs Dunbar had begged so hard that we would pay her a visit,

that we took the opportunity of every body being at their devotions to

go to her, as her house did not admit of retirement. The old Lady was

charmed to see us and we had reason to thank her for Memboe, who had

been most exact in her duty. Mr Mackinnon had taken Jack up to his

plantation, and was grown so fond of him, that he did not know how to

part with him. Billie lives much at his ease between the ship and Mrs

Dunbar's. We found Mary had been often ashore, but gave herself no

trouble about us. Indeed we had no occasion for her attendance, as

Memboe, the black wench, performed her duty in every respect to our

satisfaction. Every body who did not attend the service at Church were

gone out of town. My brother was not yet returned from his Tour, so we

had that night entirely to ourselves. Next morning atoned for this, as

every body was with us, and we were carried by Mr Halliday and Mr Martin

up to a fine plantation, which belongs to the former. We went out of

town pretty early, as .jrs Dunbar with several other Ladies were to meet

us. We met the

Negroes in joyful troops on the way to town with their Merchandize. It

was one of the most beautiful sights I ever saw. They were universally

clad in white Muslin: the men in loose drawers and waistcoats, the women

in jackets and petticoats; the men wore black caps, the women had

handkerchiefs of gauze or silk, which they wore in the fashion of

turbans. [The "tenah" was the negro woman's headdress, composed of one

or more handkerchiefs put on in the manner of a turban. An excellent

description of the market is given by the author of the Brief Account.

"This market is held at the southern extremity of the town ... here an

assemblage of many hundred negroes and mulattoes expose for sale

poultry, pigs, kids, vegetables, fruit and other things they begin to

assemble by day-break and the market is generally crowded by ten

o'clock. This is the proper time to purchase for the week such things as

are not perishable. The noise occasioned by the jabber of the negroes

and the squalling and cries of the children basking in the sun exceeds

anything I ever heard in a London market. About three o'clock the

business is nearly over." The writer goes on to discuss the obnoxious

odors, the drinking of grog, the gambling and fighting, etc., which

accompanied the holding of the market (pp. 139-141).] Both men and women

carried neat white wicker-baskets on their heads, which they balanced as

our Milk maids do their pails. These contained the various articles for

Market, in one a little kid raised its head from amongst flowers of

every hue, which were thrown over to guard it from the heat; here a

lamb, there a Turkey or a pig, all covered up in the same elegant

manner, While others had their baskets filled with fruit, pine-apples

reared over each other; Grapes dangling over the loaded basket; oranges,

Shaddacks, water lemons, pomegranates, granadillas, with twenty others,

whose names I forget. They marched in a sort of regular order, and gave

the agreeable idea of a set of devotees going to sacrifice to their

Indian Gods, while the sacrifice offered just now to the Christian God

is, at this Season of all others the most proper, and I may say boldly,

the most agreeable, for it is a mercy to the creatures of the God of

mercy. At this Season the crack of the inhuman whip must not be heard,

and for some days, it is an universal Jubilee; nothing but joy and

pleasantry to be seen or heard, while every Negro infant can tell you,

that he owes this happiness to the good Buccara God, [White men's God.]

that he be no hard Master, but loves a good black man as well as a

Buccara man, and that Master will die bad death, if he hurt poor Negro

in his good day. It is necessary however to keep a look Out during this

season of unbounded freedom; and every man on the Island is in arms and

patrols go all round the different plantations as well as keep guard in

the town. They are an excellent disciplined Militia and make a very

military appearance. [The militia of Antigua consisted of a troop of

horse,—carabineers or light dragoons,—three regiments of foot, known as

the red, blue, and green, one independent company of foot, and one

company of artillery. Service in the militia was obligatory from 14 to

45. Colonel Martin was at the head of these forces for upwards of forty

years. In 1773 Sir Ralph Payne became colonel of the carabineers.] My

dear old Coll, was their commander upwards of forty years, and resigned

his command only two years ago, yet says with his usual spirits, if his

country need his service, he is ready again to resume his arms.

Every body here is fond of dancing, and

[they] have frequent balls. We have been at several, very elegant and

heart- some, particularly one at a Doctor Muir's, [Dr. John Muir married

Eleanor Knight in 1757. He died in 1798. Their daughters were Fanny's

boarding school acquaintances in Scotland and must have been about her

own age.] whose daughters were Fanny's boarding school acquaintance,

fine girls, with a most excellent mother, who tho' even beyond

Embonpoint began the ball and danced the whole evening, with her family

and friends, as did several other Ladies, whose appearance did not

promise much strength or agility. Sir Ralph and Lady Payn are now come

back, but Lady Payn so ill that she has never been out of bed since her

arrival. Every body is melancholy on account of her illness, for by all

accounts this amiable creature must soon fall a sacrifice to this

climate, if she is not soon removed from it. [Governor Payne's

correspondence confirms Miss Schaw's statements in all particulars. The

governor left Antigua with Lady Payne, in the summer Of 1774, for a tour

of the islands under his jurisdiction, and was away when Miss Schaw

arrived. He was at St. Christopher in October and soon after. wards at

Montserrat, returning to Antigua after Christmas but before the end of

the year. As his wife was in poor health, he had already applied to Lord

Dartmouth for permission to go to England and found the secretary's

letter of consent awaiting him on his return. In a letter of February 7,

1775, he wrote Dartmouth: "Lord Mansfield's intercession with your

Lordship for his Majesty's permission for me to conduct Lady Payne to

England, for the reestablishment of her health, does me the greatest

honour. I have indeed for a twelvemonth past entertained the most

anxious desire of paying a short visit to England, but did [not make

application] until the month of last October, when Lady Payne's health

appeared to me to have arrived at so dangerous a crisis (and my own was

so materially impair'd as to create a despair in me of its

reestablishment without the aid of a northern climate) that I determined

to submit my domestic situation to your Lordship's humanity" (Public

Record Office, C. O. 152: 55). He said further that Lady Payne had not

quitted her bedchamber twice in the "last six weeks." Dating back from

February 7, this would bring the return to Antigua to December 27, two

days after Christmas, which accords well with Miss Schaw's remarks.]

My brother has been

returned these two days, and is so charmed with the other Islands,