|

Nobantu—Hospitality—The

Visitors—Lord Milner—General Gordon—Baron Rothschild—Entertaining the

Natives— Happy Effects of a Visit to Lovedale.

‘Hjertrum, Husrum’

(Heart-room makes house-room).—Lapp

Proverb.

‘We are Allah’s guests in the

Desert: strangers are sent to us by Allah: we are to receive them as

Allah, the Merciful and Bountiful, has received us: the guest is the Lord

of the house and we are his servants.

‘—From the Creed of an Arab Chief concerning

Hospitality.

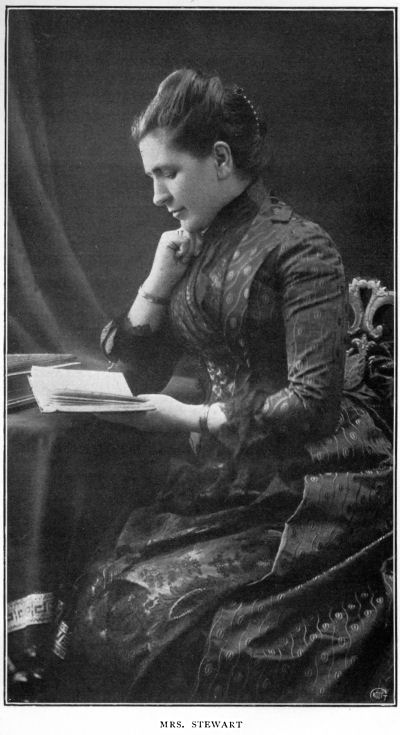

STEWART’S

work cannot be understood without a due

appreciation of his home-life.

Instead of speaking of Dr. Stewart

of Lovedale, his friends would naturally speak of Dr. and Mrs. Stewart.

She was a large part of the Institution, and one with her husband in mind

and heart. ‘They brought duality near to the borders of identity,’ as

Gladstone said of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Often at night, when

all the rest in the house were in bed, they would spend an hour in

consultation and prayer about their work.

In her own sphere she was as

influential as he was in his. He always maintained that she was wiser and

more efficient than himself. He thoroughly appreciated the spirit in which

she accepted the trials and anxieties inseparable from his pioneering

work. He wrote: ‘Her complete sympathy with missionary work and her sound

judgment and activity have been a great source of strength to me.’ The

Report of Lovedale for 1906 closes with these words: ‘To her many other

gracious gifts Mrs. Stewart added that of a gifted speaker, a capable

organiser, and one whose personal influence was very marked. Forty years

of such service in Love-dale is a great and worthy record.’ The native

name for Mrs. Stewart was ‘Nobantu,’ the mother of the people.

His many letters to his children reveal the father’s

heart. Several of them are long and carefully printed for the tiny reader.

Here is one addressed to his ‘dear wee singing bird ‘:—

‘How I miss your singing in the

morning... I try to recall that sweet smile of yours—sweet to look

at—sweeter still to remember—and sweetest of all to see again if God shall

so spare us.

‘A gift of God you are to us. May He

who has given you, long continue the gift to gladden us and freshen all

our lives. Sweet token of God’s love, may you be one of His own, made

still purer and sweeter by the Spirit’s grace and the Lamb’s blood.’

Again he writes:—

‘I will tell you now what I am

doing. I go about the streets and into the offices, and I say to this man,

"Give me a hundred pounds for Lovedale," and to another who is not so rich

I say, "Give me fifty pounds." And they give me that money, and I thank

them before I go, and thank God too, because it is He that puts it into

the hearts of these men to give me money for Lovedale. And they give it

because they love Christ and have already given Him their hearts.

‘Now I am going to ask

you to give

Jesus some-thing too. Go into the garden and see if there are any flowers.

Then go into another garden and you will find a flower. Take it and say,

"Lord Jesus, I have nothing else to give you. But I give you this; it is a

little flower, it is my heart. I give it to you because you love me. You

loved me so much that long ago you died for me. And now I give the little

flower of my life, and I pray to you:

"In the Kingdom of Thy grace

Give a little child a place."

And He wili give you that place, and

you will be a glad and happy little girl, and we shall be so happy when we

hear that you have given this little flower to Christ.

‘Do you remember London, that great

place, nothing but houses and people, nearly as far as from Lovedale to

Beaufort? There are many poor children in London, and when I see them, I

think of you and F. . . . Do you remember anything I said about a little

flower in one of my letters? What has become of it?

‘I am wearying to see you, and hope

to come in two months after you get this. I hope you will pull hard on the

ropes and make the ship come fast to Cape Town.

‘. . . There is the line of a hymn that has been in my

mind this morning—it is this:

"I heard the voice of Jesus

say

Come unto me and rest.

Lay down, thou little one, lay down

Thy head upon my breast."

‘Now, dear little M., I should like

if you could tell me some day that you had heard Jesus say this, and that

you had just done what He bids you. He is very good and kind to those who

come to Him.’

One of his daughters writes:—

‘All I can say is that as each year

goes by I miss father’s wonderful tenderness and sympathy more and more. I

often think of his love and gentleness to M. (a grandson) during the war.

[M.’s father was the little boy from whose wounds Dr. Stewart sucked the

poison. See p. 99.] In the study at Lovedale I sometimes found the two

with their fingers all inky, and father so pleased and laughing because M.

was "making his fingers like Grand-daddy’s, and Granddaddy was a dirty boy

too." I was not allowed to take the wee chap away, as they "were enjoying

themselves," father said.’

They had one son and eight

daughters, one of whom died early. Their large, happy, and loyal family

was an effective object-lesson upon the Christian home, and a source of

power to the mission.

Their son for some time assisted his

father in the office at Lovedale, and is now in business in South Africa.

Three of his daughters are married—two in South Africa, and one in

Scotland. Another daughter was on the teaching staff at Lovedale.

The hospitality at Lovedale was

unbounded. They had heart-room for all their guests; but as the children

knew right well, they were often puzzled to find house-room. Especially in

the early days when their house was small, Dr. and Mrs. Stewart often

slept in the study, while their children slept on the floor, or in

outhouses, or were billeted among the teachers. When the new house was

built, Dr. and Mrs. Stewart’s friends spent upon it £800 in addition to

the sum granted by the Committee. Their idea of hospitality was like that

of the Arab chief in Bible lands. He gallops on his swiftest steed to

welcome, the coming stranger. Stewart surpassed him, for when he learned

that a friend of his or of the mission was in the land, he flashed a

telegraphic invitation to him. The Principal’s house was thus a hostelry.

It was as much addicted to hospitality as were the hospices of the Middle

Ages, but with a difference. These had been richly endowed for the very

purpose of entertaining travellers, whereas the hospice of Lovedale was

endowed out of the patrimony of the missionary’s family.

From all parts of the world visitors

came to Love-dale. Before the railway reached his neighbourhood, Stewart’s

‘spider’ and horses had often to be sent twenty, thirty, forty, or sixty

miles to the nearest railway station to meet his guests. He required five

or six horses, and they were at the service of the staff. Dr. and Mrs.

Stewart kept open house, and almost every week they were speeding the

parting and welcoming the coming guest. If the family had kept a visitors’

book, it would have been a bulky volume. There was a hearty welcome for

all, especially for those who were opposed to missions. They might stay as

long as they liked and examine every department of the Institution. They

had often from one to thirteen guests at a time. During six months the

family never once sat down alone at the table. A frequent guest writes:

‘It was Mrs. Stewart’s kindness and winsome graciousness which made the

Principal’s home at Lovedale the most hospitable in South Africa. At times

she was the ministering presence, at others the wise and trusted

counsellor, with a woman’s clear discernment and instinct; at others again

the worker and the helper, ever ready to ease the burden and further the

great cause.’

Another writes: ‘Jesuit fathers,

[Seven Roman Catholic priests once sat down together at their table.]

ministers of the Dutch Church, an Anglican archbishop, a visiting

deputation from Scotland—all alike were welcome, and all alike went away

delighted with Dr. Stewart’s generous hospitality, his kindly

consideration, and, above all, the fascination of his conversation. He was

a close personal friend of men like General Gordon, Edmund Garrett, Sir

Bartle Frere, Cecil Rhodes, and Lord Milner. No one who knew him or his

work could have failed to come under the spell of his imagination.’

The missionaries on the staff were

usually the inmates of the family till they got a home of their own. One

of them writes: ‘I felt at home with Mrs. Stewart from the first hour.’

The staff usually had a social meeting in the Principal’s house every

Monday evening, and also at other times to meet some distinguished

visitor.

Stewart thoroughly enjoyed congenial

society, though his abundant labours left him little time for it. When

free, he was eminently ‘clubbable,’ and he made friends among all classes.

His Ulyssean experience of men and cities had given him a rich fund of

incident of travel, but his rooted aversion to speaking about himself

rarely allowed him to give bits from his own Odyssey.

‘He was very fond of good music,

especially of plaintive music—that which holds within it the "sad, low

notes of our humanity," like the best Scottish song. Joined to his love of

music was his delight in art of all kinds. Much of this no doubt came from

his love of all that was beautiful and harmonious.’

The Rev. J. E. Somerville, B.D., of

Mentone, writes:

‘No words are sufficient to express

the admiration which Dr. Stewart’s whole bearing and conversation

awakened. Anax andron Agamemnon (Agamemnon, prince of men) were the

words that came to one’s lips. He was a giant in every sense of the term.

. . . On Saturday he was engaged till late at night with Kafirs, who came

to talk about things temporal and spiritual. . . . I came away from

Lovedale and the happy and beautiful family in its manse thanking God that

He had given us as a missionary one of the grandest men it has been my

privilege to know.’

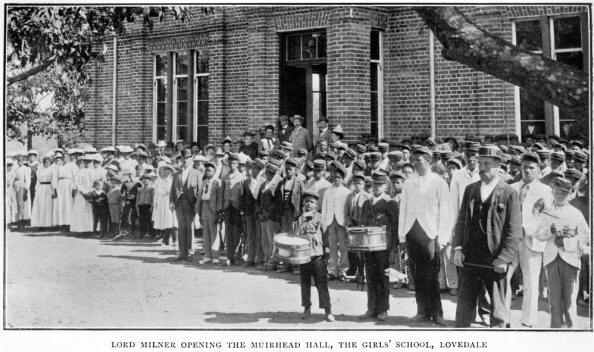

Dr. Roberts writes: ‘Lord Milner had

a warm affection for him. About the last letter he wrote from Government

House, amid the press of many distracting concerns, was the following

good-bye to Dr. Stewart:—

"GOVERNMENT HOUSE,

"JOHANNESBURG, 2nd April 1905.

"DEAR DR. STEWART,—I cannot leave

South Africa without sending you one line of farewell. I am living in a

perfect whirl, and hardly know what I am doing. But I shall often think,

in moments of greater leisure, with pleasure and gratitude of your

friendship.—With deepest esteem and all good wishes, yours very sincerely,

MILNER."

‘Lord Milner spent four or five days

at Lovedale, gleaning facts about native affairs. He opened a new hail,

and declared that Dr. Stewart was "the biggest human in South Africa."

‘The deep affection that Gordon had

for him is well known. When the hero of Khartoum was at Lovedale in 1882,

the comradeship of the two men was pleasant to see. There was a remarkable

affinity and a striking similarity between them.’

After one of his visits General Gordon wrote: ‘I am

truly sorry to leave your quiet abode and come back into a whirl.’ When

leaving South Africa in 1882, he wrote :—

‘Mv DEAR DR. STEWART,—! am sorry to

leave without seeing you and Mrs. Stewart and your family and my friends

at Lovedale. I leave for England via Natal on Tuesday or Wednesday

next. I am sorry I could not do anything for the Colony except write

reports. My heart often goes out to you all. I should wish to have seen

more of you.— With kindest regards to Mrs. Stewart, yourself, and the

children, and trusting for help to your prayers, believe me, my dear

friend, yours sincerely,

‘C. E. GORDON.’

Stewart’s only son was called James

Gordon as a memorial of this friendship.

Visitors of all creeds came from

nearly all parts of the world. Among these were Baron Rothschild, who

wrote: ‘I think our visit to Lovedale was the most interesting part of our

journey in South Africa.’

A special welcome was given to young

missionaries who wished to inquire about missionary methods.

The native often came for counsel

about his trivial affairs. Stewart shook hands with his humble guest, took

him straight to the kitchen for refreshments. He would listen patiently to

the poor man’s story. People used to say that a native could get what he

wanted from the Principal far more easily than a white man could. Often

food was sent daily to sick natives in the neighbouring location. Dr. and

Mrs. Stewart were the Lord and Lady Bountiful of the Tyumie Valley. Many

thought that they were generous to a fault. ‘The old people of the

Love-dale location,’ writes one of his staff, ‘were his special charge.

Every Sunday there was a dinner-party of old men at the house, and if any

were too feeble to come for it, the meal was sent to them.’ They also knew

that he had a canvas bag in which he kept money for helping the needy.

Towards his poorest guests Stewart’s

was no bare giving. It was rather the spontaneous outflow of the heart

than the outcome of intention or endeavour; and it was done with a

refinement of Christian charity and chivalry. He thus enlarged the joys he

possessed by sharing those he bestowed.

This splendid hospitality was a

powerful aid to the mission. A visit to Lovedale often made a deep

impression upon visitors who were sceptical about missions. The splendid

avenue, the well-kept gardens; the happy family; the thoroughly competent

staff; the hive-like hum of happy activity; the immense array of young

life; the girls tripping along, their eyes full of girlish merriment, in

striking contrast with the sheep-like, ox-like stare of their heathen

sisters at the kraals; the genius of the place—all these united to create

the right mood in the critic.

Mr. Bryce, in his Impressions of

South Africa, p. 374, thus describes Lovedale: ‘It is admitted even by

those who are least friendly to mission-work to have rendered immense

service to the native. I visited it, and was greatly struck by the tone

and spirit which seemed to pervade it, a spiril whose results are seen in

the character and career of many of its graduates. A race in the present

condition of the Kafirs needs nothing more than the creation of a body of

intelligent and educated persons of its own blood, who are able to enter

into the difficulties of their humble kinsfolk and guide them wisely. Dr.

Stewart possesses the best kind of missionary temperament, in which a

hopeful spirit and an inexhaustible sympathy are balanced by Scottish

shrewdness and cool judgment.’

When Stewart heard that there were

severe critics of missions in the neighbourhood, he used to say: ‘Ask them

over, and let them see the work and judge for themselves.’ Regarding a

sceptical critic on missions, the late R. W. Barbour of Bonskeid

wrote: ‘A visit to Lovedale gave him new light. If it were nothing else,

that home at Lovedale does a work that one cannot well value, in disarming

prejudice and affording at least the opportunity to some who would

otherwise not see what was going on, to give the natives a helping hand.’

Mr. Barbour himself was so

fascinated by Love-dale that he seriously considered whether he should

devote himself to it as an honorary missionary. Dr. George Adam Smith

tells us that when visiting Africa, ‘Mr. Barbour came under another of the

great influences of his life—Dr. Stewart of Lovedale.’

J.

S. Macarthur, Esq., the discoverer of the

cyanide gold-extracting process, thus describes his visit to Lovedale: ‘I

was impressed by Dr. Stewart’s quiet, strong, kindly manner.. With him

there was no excitement, no noise, everything went smoothly and

peacefully, but everything did go. . . . I left

on Monday afternoon, having spent in Lovedale two of the quietest

and happiest days of my life. Whilst there I did not know in the least

that Dr. Stewart was teaching me—I do not think he knew—but after I left I

found that I knew very much more than when I went. He had impressed on me

the foolishness of trying to convert a heathen and then leave him idle to

drop back into his old, lazy, loafing, quarrelling ways.’

Let another example stand for many.

A visitor to Lovedale thus describes his experience, in one of the African

newspapers: ‘After welcoming me to Lovedale, Dr. Stewart invited me to

have a look over the place, and here it was that all the arguments that I

had prepared, vanished as chaff before the wind. For one of the first

observations the doctor made was this: "Our object is to teach the native

to work; work he must a certain portion of the day, or go. We cannot

afford to keep idlers here; lazy fellows must leave us. We endeavour to

civilise and teach them to fear God at the same time, and hope that some

at least will turn out useful men and women." I could scarcely avoid

applauding the doctor’s sentiments, with a hearty "hear, hear," having all

the ground knocked from under me. . . . I left, convinced that the

Institution ought to have every support and encouragement.’

This visitor might have added: ‘I

came; I saw; I was conquered.’ |