|

On the 8th of July, 1902,

Mrs. Dollar and I sailed on the then crack steamer "China" of the

Pacific Mail fleet. We had an interesting but uneventful trip until we

reached Yokohama, We also visited Tokio and Kobe.

The trip from Kobe

through the Inland Sea was beautiful. The thousands of small islands,

all more or less wooded and many of them cultivated, with the hillsides

terraced to the top. gave a fine scenic effect. The sea is well named.

Sometimes it is many miles wide, then there are narrows less than a half

mile across. The formation is volcanic, many of the hills being very

steep and sharp.

INLAND SEA

The

thing that impressed me most after we sighted the coast of Japan was the

number of boats engaged in fishing The whole coast was alive with them.

At night the lights were so numerous it looked just like a lighted city.

Many times I could not believe that they were not cities, there were so

many boats m this Inland Sea. At any time we could count several

hundred, but when we came to Shirnonoseki Straits they were so numerous

the steamer had to slow down "dead slow" and keep blowing the whistle

continuously to get a passage through them. They were of all shapes and

sizes from the old junk, made many years ago mostly of bamboo, to

sanpans fifteen feet long. The junks have high bow and stern twenty to

twenty-five feet out of the water with a freeboard of from three to four

feet amidships. Then there were lots of fore and aft schooners, not bad

looking but too dumpy, too much beam for their length. The sampans are

four to five feet wide, three feet deep, one or two masts and a long

pointed bow eight to ten feet long, which is of no use.

This

blockade continued past Moji and Shimonoseki. opposite each other, near

the outer or western end of the Inland Sea. There we saw a great many

steamers, mostly English tramps, either loading coal cargoes or taking

bunker coal. Coal is about the only business going on there.

Nagasaki is typically Japanese, with a population of probably thirty to

forty thousand. We climbed over two hundred steps to a temple on the top

of the hill overlooking the town and harbor. This is called the "Bronze

Horse Temple," there being a large horse of bronze in the square. Some

deer and other animals were there too. From this elevation it looked as

if the town was built solid, and we could see nothing but roofs, not

even the sign of a street. They have a good water works and the sewers

are all open and made of good masonry.

No

houses have more than two stories, and most of them have only one. The

stores are very small, a large one would be fifteen or twenty feet by

thirty feet. The streets are from ten to twelve feet wide and crooked,

but very well paved, mostly for jinrickshaws and hand carts. It is a

rare sight to see a horse, and then they are very small; there are some

oxen, but they carry their loads on their backs. The men are also beasts

of burden.

Before leaving Nagasaki we took on twelve hundred tons of coal in seven

hours. There were about four hundred men and women engaged in the work,

and as it was all handed up in small baskets passed from one to another,

the work went on very fast.

When

we passed out we noticed that, like all Japanese ports, it was fortified

on every available point, evidently-getting ready for the inevitable war

of European nations in the Far East.

We

crossed over the China Sea to Shanghai. The steamer had to lay off

Woosung at the mouth of the Whangpoa River, Shanghai being twelve miles

distant up the river. Woosung is at the junction of the Whangpoa with

the mighty Yangtsze Kiang, and at this point the river is several miles

wide. The channel to Shanghai is narrow and crooked and quite shallow in

places, caused by the constant washing in of the banks. There has been

considerable talk of changing this, and making a good, straight channel

with sufficient water. (All this has been done, and now a vessel drawing

twenty five feet can go direct to Shanghai at any high tide.)

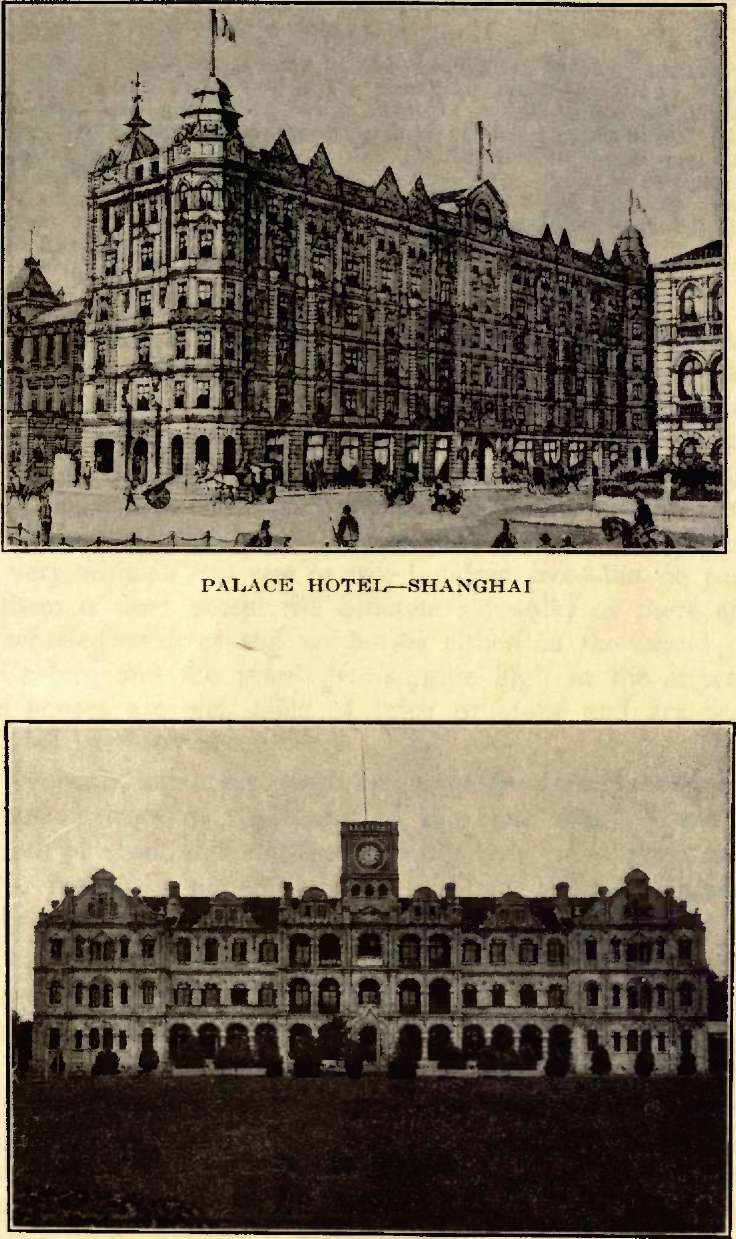

SHANGHAI

At

the first sight of Shanghai I got the impression of its being a great

commercial city, but on closer inspection I came to the conclusion it

required a great: deal to bring it up to that standard. (All this has

been accomplished in later years.) The old city proper is walled in and

is closely built up of mostly small-sized buildings, narrow, crooked

streets and containing a mass of humanity. Then there are what are

called the Settlements. Farthest up is the French, next the British, and

then what is called the American. [Unfortunately,

the American Government did not have the foresight nor the ordinary

far-seeing business sumption to hang on to their site, but let it slip

through their fingers. And now, in order to remove our Consulate from a

miserable back street, our Government had to buy a site in 1916. and had

to pay $300,000,000 for what they had had a few years ago f'or nothing.

The British were looking to the future commerce of China, and retained a

beautiful site of fifty acres for their Consulate right in

the middle of this great commercial city. Our Government is slowly

waking up to the fact that to be a

truly great nation we must have foreign trade

and lots of it. We used to think we were sufficient unto ourselves, but

this is past and a new era has begun.]

But

to come back to old Shanghai. Along the river side and extending back a

half mile going towards Woosung is what is called Hongkew, which was the

American concession and where a large Chinese settlement has sprung up

across the river, steamship companies were just making their first moves

to get wharves and terminals, but little had been done at this time.

This is called Pootung.

The

name, Shanghai, means a city by the sea. At one time the waters of the

China Sea covered the present site of the city. The land is an alluvial

soil, perfectly level, and cut up by innumerable small creeks, most of

which are now filled up. The largest, Soochow Creek, divides what was

the American concession from the British concession. The Yankinpang,

another creek which has filled in, separates the French and British

concessions. The old Chinese city was surrounded by a wall, part of

which has been taken down and made into a wide street.

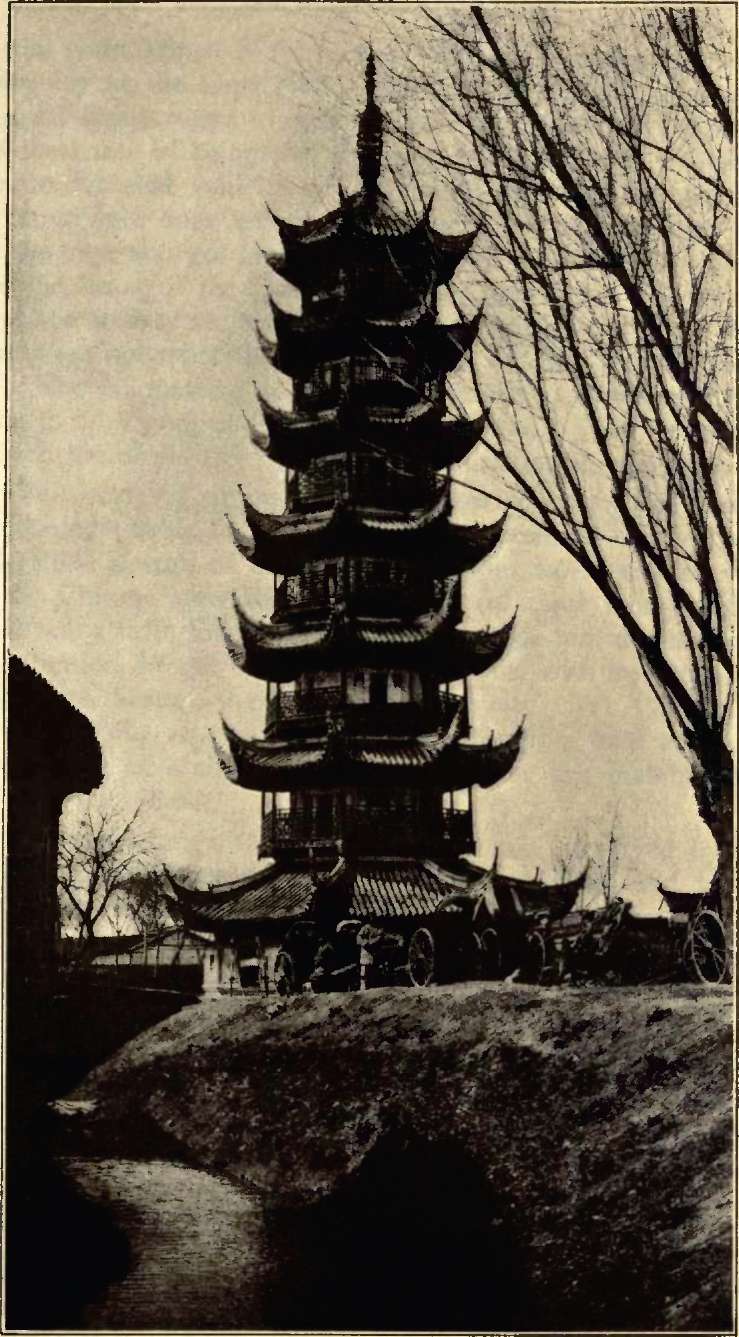

TECHNICAL DEPARTMENT BUILDING—SHANGHAI

Back

of each settlement is the residential section, but since that visit,

sixteen years ago, it has grown

beyond recognition. What were fields are now filled with beautiful homes

and well paved streets. Since that time street cars have been

introduced. The population has nearly doubled, as now there are about

one and one quarter million foreigners and Chinese. But it is in

commerce that the greatest progress has been made, and I am sure the

most sanguine could not even come near to estimating what it will be in

the next fifty years.

CANTON

At

Canton the foreigners all live on the island or Shameen, as it is

called, for protection. Two bridges connect it with Canton, and the

gates are shut at sundown. The Victoria Hotel is the only one there. The

lower part of the island belongs to the French and the English own about

two-thirds of the upper end, which is all owned and occupied by the

consulates and business houses of various nations. The streets are very

wide—about one or two hundred feet—but no part of them is used except

the concrete sidewalks as there are no wheeled vehicles and no horses

either on the island or in Canton, and the grass grows quite high in the

streets. The houses are well built of brick or stone and are surrounded

by many shade trees.

Gunboats, small war ships, and light draft cargo steamers anchor in

front of the island on the river side. There is a depth of about

eighteen feet of water here, but a great deal of the freight is carried

from and to Hong Kong in Chinese junks and other craft.

Early

in the morning, with a guide, we crossed the bridge over the canal

between the island and the city. We each had four men carrying us in

chirrs. The streets of the city are all about the same, six to eight

feet wide, and straight only for about one hundred feet at a stretch;

some have gradual bends and some very sharp curves. The houses are

generally of bamboo, having one or two stories, and bamboo matting is

stretched across from the top of one house to the opposite one, shading

the sun from the street, so that in passing through the city one rarely

sees the sun.

The

streets are so narrow there is barely room to pass two chairs and, as

everything is carried on men's shoulder's, the streets are very

congested at times and it is quite difficult to get along, but the

carriers are expert at crowding, and so manage to push through. We met

men carrying almost every conceivable thing: logs, stone, brick, mortar,

goods for export, and goods imported; we also met a funeral with a band

and men carrying the great heavy coffin, which was like a log of wood.

THE CITY OF THE DEAD

A

very interesting sight was the City of the Dead. It is all walled by

long rows of one story buildings, containing apartments mostly twenty by

ten feet in area—some thirty by fifteen feet. Each apartment contains

one coffin only, of people who have died many years ago. The coffin

rests in the middle of the room on a stand, beside which there is a

table and chairs, with tea and cakes replenished every morning, and a

light is kept continually burning for the spirit when it returns. These

are only the abodes of the very rich dead, and it is all beautifully

kept up through all these years. The coffins are of the most beautiful

workmanship I have ever seen, many of them being of ebony, polished to

the highest degree. They are mostly round and resemble the cut off a

log.

We

took lunch at the five-story pagoda which is on a hill at the City Wall.

The City Wall is about thirty feet wide at the top, one hundred and

fifty feet at the bottom and thirty feet high, in some places much more.

The pagoda overlooks the entire city, and is about one hundred and fifty

feet square at the bottom and sixty to seventy feet at the top, each

story being about fifty feet in height. It is very much neglected, and,

like the Empire, is fast going to decay The fortifications on the wall

and at this place would have been good one hundred and fifty years ago,

but are now of no use. The cannons are on wooden carriages, and many

have rotted away until they have fallen down.

Looking down from the pagoda the river is very pretty, and many of the

canals that run through the city can be seen, but the streets, being so

narrow and croaked, cannot be seen at all so that it looks like one mass

of roofs, but the foreign settlement looms up better. The French church

and the pawn shops are the only remarkable buildings. The pawn shops are

square, stone buildings, say thirty to fifty feet square and six or

eight stories high, with small windows. They look like watch towers. In

the number of joss houses and temples this city is well supplied. I

cannot give an idea of their number but we were continually passing them

all day, from the small stone altar, to the great gorgeous ones; our own

San Francisco Chinatown joss houses resemble them, on a small scale.

I was

interested in the lumber yards, of which there are a great many, which

mostly supply wood for coffins. It takes a good big log to make a coffin

as they are round and hollowed out like a dug-out canoe. You can imagine

the job it would be for men to carry the logs through the narrow,

crooked streets to the various yards from the river or canals, where

they are sawn into lumber by hand. If the lumber must be dried. it is

spread out on the roofs of the houses in the sun. American lumber was

only conspicuous by its absence.

Previously the people had not met many foreigners and were not at all

friendly, as we could see by the looks of disgust on their faces how

they hated us.

It

was not safe for us to stop unless we got inside of closed doors.

Whenever we halted on the streets we could only stop for a few seconds

as the crowd would immediately gather from all directions, and we would

be jammed in and could not get out. Mrs. Dollar's hat was the star

attraction for the women and children wherever we went.

SWATOW

Dropping back to Hong

Kong, we left that city on the Japanese steamer "Auping Maru" for Swatow

and Amoy. We were the only Americans or Europeans on board. The entrance

to Swatow is among rocky islands, with channels somewhat narrow and

crooked. The town is up the river about three miles from the ocean, but

the river has a good width. Before coming to an anchor the steamer was

surrounded by a multitude of small sampans of all kinds and

descriptions, all propelled by being sculled when coming at full speed.

Some of the more adventurous ones, runners for Chinese boarding houses,

came on board in this way: they had long bamboo poles with an iron hook

on the end and they would hook this on the iron fife rail and come on

board by putting their feet against the side of the ship and climbing up

over the rail, It was quite a sight, and when the steamer slowed down we

were fairly crowded with them, I should say three hundred came on board,

all clamoring for patronage, either to go ashore with them or to go to

their hoarding houses.

When

we made fast to the company's buoy, about five hundred feet from shore,

all kinds of peddlers came aboard, even women trying to get clothes to

mend. We had a large number of Chinese passengers and a lot of freight

to put off. After breakfast we went ashore and through the town. The

town is occupied by warehouses (Godowns, so called) and the few European

offices, which are generally enclosed within a high stone wall.

Swatow has somewhat the appearance of a European town, the style of

houses being somewhat of that kind, although the streets are narrow and

crooked with the usual smells and dirt. We saw a temple in which there

was some very fine carving, also some bas-reliefs on the wall enclosing

the place. They were very large and represented dragons and mythical

deities, mostly of pottery painted in gaudy-colors; the place was very

dirty, and, to add to that, a lot of hogs were roaming around the court

yard.

They

are improving the water front and building a sea wall at Swatow. There

are many steamers running in here from various parts of China and

several from Singapore. When we were there a large four-masted steamer

sailed for Java with eighteen hundred coolies. We took a lot of liquid

indigo from here to Amoy.

AMOY

The

entrance to Amoy, like Swatow, is among islands and is narrow and

crooked. The city is about, seven miles up the river, which is fairly

wide and of good depth. Our vessel lay at the Caps buoy, four hundred

feet from shore. A great crowd came to meet us here as at Swatow. Amoy

has the name of being the dirtiest city in the world. There are no

wheeled vehicles of any kind here, and no chairs except private ones, so

we had to walk. We started out to see the city, and got along all right

until we progressed well into the heart of the place. In a city like San

Francisco it would be an easy matter to get out, but not so here where

the streets are not more than six feet wide and are covered over with

bamboo matting to keep out the sun, and where they come to an abrupt

ending with a stone wall (This is done to keep the devils from running

straight through the town.)

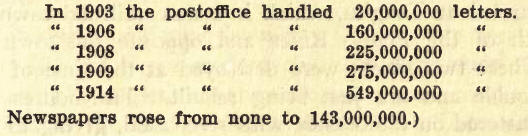

A CHINESE PAGODA

We

wandered around without knowing where we were going, and unable to make

inquiries as none of the natives understood a word of English when, in

our worst, straits, one of the Chinese stewards from the vessel came

along. He could talk a little English, and after we made him understand

our situation, he got an old man to pilot us, with instructions to take

us through the best part of the city. We found, to get out of our fix,

we had to pass through a gate and up some flights of stairs, which

accounted for our inability to find our way about.

It

seems strange to go into a store and be served by a man having nothing

on him but a pair of pants and very short ones at that; there are no

sales ladies out here.

Children until they are six or eight years old have nothing on them at

all, but the girls and women are very modestly and generally neatly

attired and their hair is always done up neatly. It was also strange to

see us going along with an umbrella to keep the scorching sun from us

and note the natives going along not only bare headed, but with all the

front part of their heads shaved clean. The sun does not seem to have

any effect on their naked bodies.

This

is the great tea exporting port. Most of the tea comes from the Island

of Formosa, twelve hours' steaming from here. It is all brought over in

small steamers of less than one thousand tons register, and put in

warehouses to be repacked and reshipped to nearly every part of the

world. A great deal of it goes to New York.

(Since the foregoing was written, what a change has taken place. The tea

of Formosa is all exported by Japanese and shipped from the new seaport

of Keelung, which place was unknown at that lime. Tarn Sui was then the

largest port of Formosa, and was only for small vessels drawing not more

than twelve feet of water.)

SHANGHAI

From

Amoy we sailed for Woo-sung and from there returned to Shanghai.

One

peculiarity of Shanghai is the wheelbarrow in use. The wheel is about

three feet in diameter, and the body is larger than our largest ones.

The coolies carry passengers in these, sometimes three people on each

side, their feet hanging down. The man has a strap over his shoulders by

which he carries the weight. They carry immense loads of merchandise,

bricks, stone, furniture, and, in fact, anything. I saw one man wheeling

a barrow with a hog on one side and a man on the other (Only the Chinese

patronize them; the whites use the rickshaws.) There are no chairs but a

great deal of merchandise is carried on bamboo poles with two men.

The

buildings are mostly of cut stone and some brick, and the streets are

substantially- built, which gives the city a very solid appearance. One

sees a great: many European houses and blocks going up wherever one

goes. The European troops are here in great numbers and large barracks

are occupied by them. Each nation has a place of its own. and it looks

as if they intended to stay.

TSINGTAU

We

left Shangha for Tsingtau, but when we arrived off the latter port it

was blowing such a gale we were unable to land for some time. When we

did get ashore we took rickshaws and looked the town over. It appears

the Chinese had a town or village at this place, but in 1899 three

German men-of-war anchored here and sent their crews ashore to invite

the townspeople to move off about two miles. They saw there was no use

to refuse, so their town was leveled to the ground, nothing being left

except a temple. The Germans then laid out a fine city with wide

streets, and in the length of time they have occupied the place they

have done wonders. The German government made the streets and have quite

a city of modern houses, mostly large three-story blocks of stone and

brick. To date they have expended over three million dollars. No Chinese

are allowed to live in this city, but they have quite a town a short

distance off. The population is entirely German and the trade will be

exclusively for the Germans.

There

are two harbors. The town is on a peninsula with a harbor on each side.

On the north side they were building a breakwater for deep sea ships,

which would take three years to complete. The strange thing about all

this great outlay was that there was no export trade at all--all import

and nothing going out. The Germans had built one hundred and twenty

miles of railroad and were still building. They also had a few good coal

mines from which they expected to get coal in a short time. So far the

whole place was just a great military and naval camp, and the

government's money was keeping the whole thing up. This may suit the

German taxpayers but it would not go long with Americans. No one seemed

to know if there was to be much commerce or not. Some hoped if the

railroad were extended to the Grand Canal, which runs from Hangchow to

Peking, that they might tap some trade, but the country-through which

the railroad passes is non-productive.

(Many

changes have taken place here since this visit. Under almost

insurmountable difficulties the Germans kept steadily at it with one

object in view—to get there, and they did get there, as out of almost

nothing, to their credit be it said, they built up a great trade. And

when their position was assured, the war

within nations of Europe gave Japan an easy opportunity of ousting them,

and not only taking Tsingtau, but of taking possession or practically

all this part of Shantung Province. Looking at it from the German side,

it is certainly very sad and discouraging to the very enterprising

Germans who worked night and day to make a success of this enterprise

and now see it handed over to the Japanese. The only obstacle in the way

of the Japanese is Weihaiwei on the Shantung promontory, which is

occupied by the English and which to Japan must very much resemble the

proverbial wart on the man's nose)

CHEFOO

We

were ashore all one day at Chefoo. The German, English and American

Consulates are on a high point and are pleasantly located. The grounds

are well kept. The business part of the city is at the foot of the hill,

commencing at the harbor and running across the narrow peninsula to the

ocean, where there is a fine, sandy beach and a very good European

hotel, club houses, etc. Steamers of fifteen feet draft lay a quarter of

a mile out, and those of twenty four feet would have to lay off a half

mile, but there is a very good harbor for small boats, junks, etc., and

there is a great number of them, I should say running into the

thousands.

The

Chinese customs have a fine stone wharf for small boats to receive and

deliver cargo. On this wharf there was an enormous amount of merchandise

of every kind, some going out and some coming in. The waterfront is a

very busy place. A great article of export to other ports of China:s

beau cake. It is bean from which the oil has been pressed out and the

residue pressed into cakes about the size and shape of a large

grindstone, which is used as a fertilizer. Silk is extensively

manufactured here, but it is not the finest kind. The mulberry trees are

very scarce and the cocoons feed on the oak leaves which produces a

coarser kind of silk called pongee.

Not

much lumber is used here, but what there is of it is all native wood

brought in logs hewn on four sides, from Northern China and Korea.

This

city is not far from the new mouth of the Hoang-ho or Yellow River, of

whose disastrous floods we have read so much. Its mouth has changed

several hundred miles in a few hundred years. Now it empties on the

north side of the Shantung peninsula, though it has been known to empty

on the south side, many miles apart. Down this river comes the great

commerce that keeps up Chefoo.

I do

not think that I have explained that the Customs of China are under the

management of the English The Chinese could not trust their own people

for fear the officials would steal the money. They claim that under the

present arrangement the Government gets every cent paid in, it being

honestly collected and paid over. The Chinese Government has no

government post or mail service. A few companies in various cities carry

letters for short distances, but there is no general mail in China. The

European nations each have a post office of their own, and you can mail

your letter in a Japanese, English, German, or French post office, and a

letter coming in is sent to the post office of the language in which it

is written. The United States has only one, located in Shanghai. This is

causing considerable confusion. The Japanese, in Japan, have a very good

system, the same as ours.

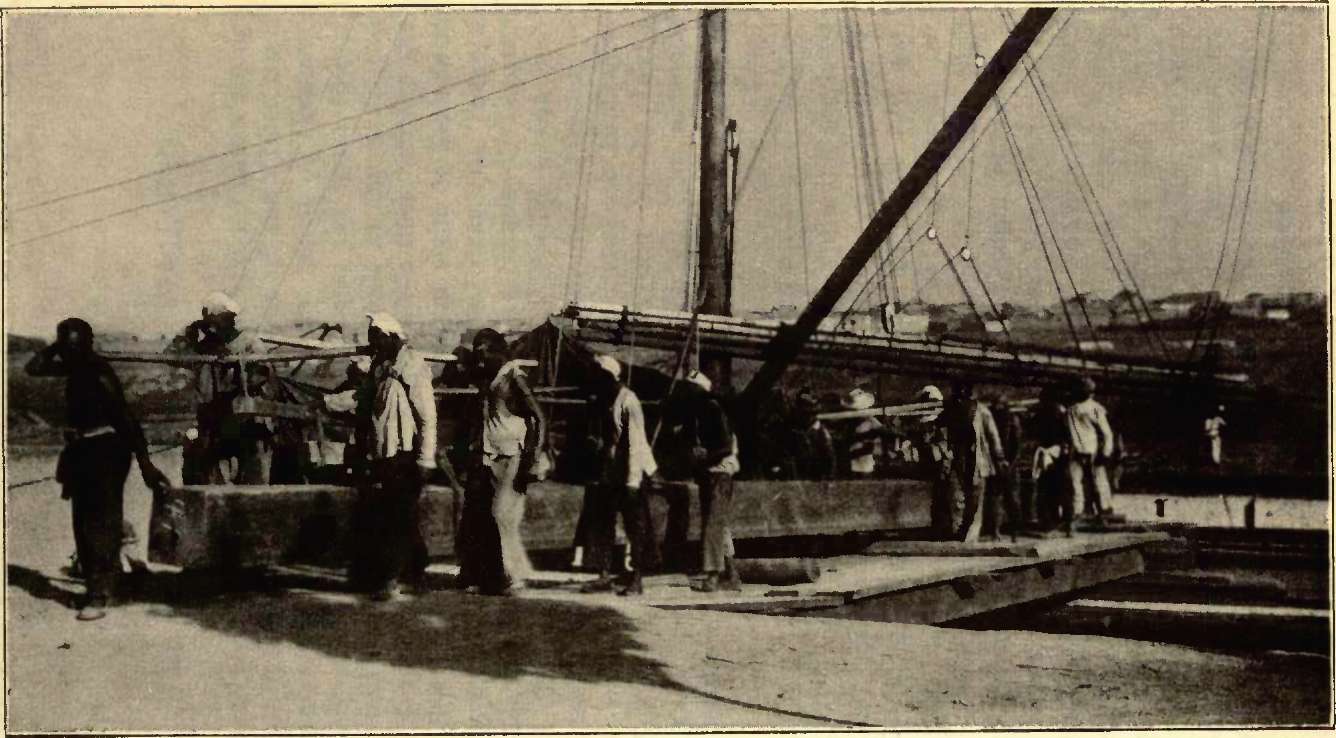

(Since this was written, the Chinese have adopted the modern post office

under government supervision, and it is a success.

The

following figures show how much of a success:

We

got chairs and went through the town. There arc no wheeled vehicles here

except wheelbarrows and they like to hear them squeak, so put no oil on

the gudgeons on purpose, and when several of them are being wheeled

together they make unearthly sounds. The streets are fairly well paved,

but a little rough although a little wider than in most Chinese cities,

being from eight to ten feet wide, full of lanes, court yards and

alleys.

We

wanted to go to a wholesale silk store. First we had to go through a

grocery store into a courtyard with beds of flowers and shrubs, along

the sides of which appeared to be restaurants; from here we went through

an alley, three feet wide and crooked, into another courtyard which was

paved, then through another three-foot alley into a small open square

twenty feet each way. On one side of this square was the store. This

will give an idea of how-business is done.

In

one part of the city there is a creek which, at this time of the year,

is nearly dry. The houses are built right up on the bank, and they use

the creek bed for a street, with a small filthy stream running through

the middle of ;t. There are a great many native houses which

are built mostly of stone, small but very substantial. The houses have

to be warm as they have plenty of cold weather and the snow often lies

on the ground for months.

We

visited an industrial school conducted by a Mr. McMullan independently

of any society. There seemed to be about fifty girls all learning

Chinese and English, and half of their time they employed in making silk

lace of very beautiful patterns. Then there was a separate part for boys

where they made brushes, and all the material that was put into these

two products was grown in this vicinity

TONGKU

We

landed at Tongku. which s a new railroad town at the mouth of the Pei ho

River and opposite the town of Taku. These two places were destroyed at

the time of the Boxer trouble and are just being rebuilt. The houses are

mostly plastered on the outside with river mud, giving to the place a

yellowish appearance, the same color as the river. The Taku forts are

now just hills of sand. All round this are the flags of the various

nations, generally a bamboo pole stuck in the ground with a flag on it;

Japanese, German and Russian flags are very much in evidence. Whether

they claim those parts or not, no one knows, but no one dares to take

one of the flags down.

The

railroad station looks like a boy's game. There are five or six sentry

boxes on the platform with a few soldiers in each, with their national

flag over them. The English were running it the day we went up to

Tientsin, but the next day the Chinese took possession, the sentry boxes

disappeared and the yellow flag of China was over all the stations. The

reason of this was that the Boxer War had just come to an end a few days

before, when the country was under martial law, and now it was being

turned over to the Chinese Government—really these were very troublous

and exciting times, and the ravages of war were in evidence on every

hand.

PEKING

On

the way to Peking we passed through a very fine country, level all the

way, most of it like gardens. Everywhere there were evidences of

war—ruined houses, many of them riddled with bullet holes. The whole

country seems to have been laid waste. The railroad was not allowed

inside the wall and, as all the gates were shut at sundown, and, as we

arrived after dark, no Chinese could get in, but they opened a small

door in the big gate to let the foreigners in. We got rickshaws inside

the wall and went to the Hotel du Nord.* The entrance was a narrow

passage way protected by a big gate or door, The hotel comprised

twenty-two small buildings walled 111 and ail of one story. In the

building, where our room was, there were only two rooms.

[*

In case an

erroneous idea may be conveyed here as to the hotels o£ Peking, I will

explain that at this time, sixteen years ago, the only hotel for

foreigners was this one, and it was a hard old place at which to stay.

At the present time the Hotel de Wagon Lits is as good as can be found

anywhere in the Far East, it having several hundred rooms. There is also

the Hotel de Peking, which Is quite good. Of course these would not

compare with the skyscrapers of New York, but they are good enough.

Peking- has undergone great changes tor the better since those days.

Street improvements, sewers, buildings, and, in fact, everything has

gone ahead to meet the advanced civilization. Just one year before we

were there the Empress Dowager had decreed that all Christians should be

put to death

At

the present time, just think of the change that has taken place. When

the President, Yuen Shai Kai, opened the Peking Young Men's

Christian Association he told Mr. Matt if he would remain if China he

would assist him to get a Young Men's Christian Association in every

large city of China. The far-seeing Confucianism see that the

evangelization of China means safety, security and a certainty of China

becoming a great and strong nation. The handwriting is on the wall.]

Peking is different from any Chinese city we have seen. It is laid out

like a modern city with good wide streets and all at right angles, but

they are not paved, so the dust was as bad as the mud would be in

winter. There are lots of wheeled vehicles, mostly carts. These have no

springs and the occupants sit on the floor of the vehicle! on matting.

Generally, they have a cover, and veils can be drawn so one inside

cannot be distinguished. Donkeys are much used for riding. You see some

the size of a big dog. often with a big man on it and a coolie running

behind with a whip to make it go. The carts are queer looking things,

having wheels built up and the axles projecting outside of the hub about

ten Inches, so that in passing one it is not well to drive too close to

it. We also saw a freight pack train of camels all loaded. There were a

great number of them ready for a journey of many hundreds of miles.

The

Chinese here are very different from the Cantonese. They are much larger

and darker, and do not talk the same dialect. The city is walled off

into many different parts: the Chinese City, Tartar City, Imperial and

Forbidden Cities, etc. like all Chinese cities there are no sewers, and

the water is drawn from wells and delivered to the houses in

wheelbarrows and carts. From the drum tower, where the drums are sounded

for the opening and closing of the gates, a very fine view of the city

can be obtained.

The

Temple of Confucius is a very fine building. There were about three

hundred priests here, and when we visited it they were all repeating

passages from Confucius, keeping-time with several drums and at

intervals to the music from a band which we could not see. All their

heads were shaven, and they wore peculiar cocked hats when outside. At

this place there is a statue of Confucius seventy-five feet high by

thirty feet wide. This temple has many buildings and large grounds with

beautiful trees. It is a beautiful building, highly ornamented in

Oriental style, but has no idols in it.

We

next visited the great Temple to Buddha. This, on the other hand, had

many idols and images of various kinds. The largest and principal one is

of three women all in gold leaf. The grounds and buildings are very

extensive, and there are many gates to go through before you reach the

"Holy of Holies," but it is not well kept up and is out of repair.

In

the walled city we passed around the Imperial City. No one is allowed in

there, and the Forbidden City is inside of it, but from the drum tower

we got a fair idea of what it is like. There are many gates and walls to

go through to get to the palace, around which there is quite a forest of

trees and a beautiful large lake. The outer wall is also surrounded by a

moat of water about one hundred feet wide.

On

the south side of the city we went through the legations and foreign

houses. Great work was going on building new and much better houses than

the old ones destroyed by the Boxers. We saw many effects of the siege

in shattered walls and houses full of bullet holes.

We

passed through the outer wall and went to see the Temple of Heaven,

which is about three or four miles outside of the outer wall. A very

wide, partly paved road, which is much out of repair, leads out past it,

being one of the principal thoroughfares from the east. The grounds are

enclosed with a high stone wall, which is three and one-half miles in

circumference. Here again there are many gates to go through, and a

Chinese gate is no ordinary affair, being a very large building highly

ornamented with carving, etc. Then we came to a large marble platform

about two hundred by four hundred feet, raised about twenty feet from

the ground. Once a year the Emperor comes here, and changes his clothes

in a tent erected for the purpose, then goes along a roadway two hundred

feet wide and one thousand feet long, all marble (all the buildings,

pavement, etc., are of white marble) to the altar of Heaven. This is a

very line building over one thousand years old, having a beautiful dome

all painted when it was built and never having been touched since, and

looking as though it were done yesterday. There is an altar at which he

kneels and prays for himself and family, then he goes about one thousand

feet further to the Temple of Heaven and prays for his people and the

nation. Part of this building was burned down a few years ago and

rebuilt. Many of the gold ornaments which had been there were stolen by

the Russian soldiers. The doors are massive and are fastened with large

nails on the outside of which are gold washers, three inches in

diameter. The building is just a large circular edifice supported by

pillars, the roof being an immense dome. The decorations and paintings

are beautiful, and the gardens are arranged beautifully also. There is a

building called the Throne Room in which the Emperor receives the

principal men of the kingdom after the ceremony. There is also a palace

in which he sleeps all night, and then he leaves for another year.

On

the way hack from the city we met many camel pack trains, mule trams,

people in rickshaws, on horseback, bicycles, on mules and asses, in

wheelbarrows, in carts and sedan chairs, and thousands on foot, all

carrying some kind of load, and the dust from that mixed multitude was

blinding,

TIENTSIN

Tientsin is twenty-five miles by rail from Taku and is eighty-seven

miles from Peking, at the mouth of the Peiho River, and is the seaport

for Peking and of great commercial importance. It is forty-seven miles

by water from Taku, owing to the crooks of the

river. For some time the river has been

silting up, but they have two dredgers at work and vessels of ten feet

can reach this city at high water. The river is so narrow we had to come

down two miles stern first before we found a place wide enough to turn

round, so navigation is rather difficult—there were two pontoon

bridges to come through. Most of the freight

comes up the river in lighters and junks. The city was about demolished

by the troops, and they are busy budding it again. The wall around the

city was destroyed and in its place they have built a fine wide street

and a good sewer.

(It

must be remembered that this short description was written a few months

after most of the city had been destroyed by the Boxers and the allied

troops. The pontoon bridges were replaced by substantial, permanent

structures, and the river has been straightened and deepened so that

navigation for vessels of twelve to fourteen feet is possible. In fact,

the city is so improved that it does not look like its former self. We

own two half city blocks fronting on the river and about the center of

the concessions, on which we have our lumber yard, offices and

warehouses.)

The

lumber imports are very great, mostly logs from Korea. Coming out of the

Yalu River I counted twenty large junks loaded with logs from twelve

inches to fourteen feet in diameter. The deck loads were about fourteen

feet high and timber four tiers wide, outhanging eight feet on each

side, and twelve feet high, The logs are hung in ropes, and when the

junk is on an even beam they just clear the water: when she lists, they

are in the water. It looks like a small donkey with great packs on each

side. They seem to be quite secure as I have never seen any out of

place. They discharge at Taku. and are rafted in rafts about twenty-five

feet wide and over one, thousand feet long, and taken on flood tide to

Tientsin, and there all sawn by hand into the sizes required. Some of

the logs are hewn on two sides, but most are square; a great number of

the round ones are used for coffins. In addition to this there is

merchandise of all kinds going in. I saw a lot of old boilers going in

to be cut into pieces. I was told the blacksmiths cut those into

anything that is wanted; a great deal being made into horseshoes, all by

hand. The exports are wool, hides, tea and coffee. The new city is

fairly well laid out. The foreign part was mostly saved, and is well

built. The streets are well paved, and there are some parks and many

shade trees.

There

are a great many military men here and lots of soldiers. The United

States is represented by a gunboat at Tongku.

CHINWANGTAO

One

great drawback is the shallowness of the bar and the fact of its being

frozen up for three or four months a year. They are starting a new port

at Chinwangtao, one hundred miles off. It never freezes and it looks as

if it is going to be the place, as vessels can lay alongside of the

wharf. At Taku the big ships lay so far out that they cannot see land.

Our steamer drew eight and one-half feet, and had to wait two days to

get a tide high enough to get iron.

The

country from Tientsin to Taku is very rich and fertile. In passing down

the river we saw lots of men irrigating their fields by dipping water

from the river in pails and carrying it to the ditches.

The

Grand Canal passes here from Hangchow; I think it is about fifteen

hundred miles long in all and was constructed many hundreds of years

ago. Truly, they are a wonderful people, this, and the building of the

Great Wall would take a civilized nation many years to build, but they

can put a few million men to work and never miss them. They claim over

four hundred million, but there is no telling how many there are, as

there are lots of places which white men have never as yet reached.

THE CHINESE METHOD OF DISCHARGING LIGHTERS—TIENTSIN |