|

AGRICULTURE

THE Highlands of Scotland,

being a purely agricultural and pastoral country, and its prosperity closely

linked with those industries, we should naturally expect that the

development of agricultural and grazing pursuits would be the chief aim of

its inhabitants, and that numerous experimental farms and agricultural

colleges should be scattered all over the country; but it is not so. The

Highland and Agricultural Society, established over one hundred years ago,

undoubtedly has done much good, and to some extent stimulated farmers to

practise improved methods of husbandry; but the local associations, or

farmers' societies, have done little more than create a wholesome rivalry

among the few cattle breeders, and it is only in some localities here and

there that experimental work has been carried on with anything like

scientific precision. [In this respect the Welsh are far in advance of us,

for-in the year 1898 a fully equipped experimental farm was established in

connection with the North Wales University College, Bangor, which had only

been in existence 16 years.]

When comparing the present

condition of agriculture with what it represented at the commencement of the

last century, notwithstanding the inferior nature of the soil and the

ungenial climate, many Highland farmers, by their shrewdness and resolute

determination, although labouring under so many difficulties, have

distinguished themselves. more than any other class of farmers perhaps any-.

where, and the great progress which agriculture has made in the

north-eastern parts of Scotland during, the last hundred years testifies to

the high position which these Highlanders now occupy as agriculturists. In

the poorer localities, particularly among the crofting class, especially in

the outer Hebrides, little advance has been made during the past one hundred

years. At the commencement of this century, agricultural prices were

exceedingly high. In 1812 wheat fetched 126s. 6d. per quarter, but gradually

it fell until in 1822 it declined to 44s. 7d. per quarter, while in 1844

wheat sold at 26s. per quarter. Notwithstanding these fluctuations, we find

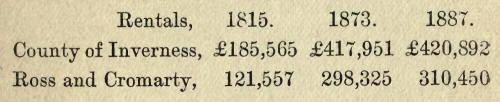

that the rentals of Inverness and Ross-shires stood as follows:—

Showing an increase in the 72

years of £235,327 on the rental of Inverness-shire, and for the combined

counties of Ross and Cromarty £188,893; from these figures—after making a

liberal deduction for increase in Burghs and valuation of Railways—we must

infer that farmers, seventy years ago, must have had a good time, or that

to-day the tillers of the soil must be labouring for nought.

Agriculture during the

present century has had a series of revivals and of corresponding

depressions. The most notable depression began about the year 1879, when a

series of bad seasons came-in succession, till affairs became so desperate

in 1879 that a Royal Commission of enquiry was. appointed to inquire into

the prevailing agricultural distress; and the Commissioners' report, which

was issued in 1882, pointed out that two of the most prevalent causes of

distress were, bad seasons and foreign competition, aggravated by increased

cost of production and heavy loss of live stock from disease.

On the strength of the

Commissioners' report Mr. Gladstone's Government, in 1883, passed the

Agricultural Holdings' Act, a measure tending in the right direction, yet

conferring on the tenant but few of the privileges which he contends he is

entitled to. Of the other legislative measures passed during last century I

need hardly mention the repeal of the Corn Laws, the Abolition of Hypothec,

the Ground Game Act, the Abolition of the Malt Tax, [Some contend that the

Abolition of the Malt Tax has been injurious to the farmer, by removing what

used to be a practical bounty on British barley. But if this was its effect,

the intention of it was undoubtedly good, and the effect was unforeseen by

the promoters of the Act.] and the Cattle Diseases Act of 1884, all measures

having a tendency to ameliorate the condition of the tenant farmer.

About a quarter of a century

ago agricultural prices stood at a remunerative figure, and the demand for

farms far exceeded the supply, resulting in fabulous prices being given for

land; and at the same period landlords were seized with a mania for creating

large farms, and consequently hundreds of the small tenants were evicted,

and sometimes as many as a dozen holdings were rolled into one vast farm.

Men of capital readily took up every farm in the market, many of them on

long leases; but a series of bad seasons landed most of these large farmers

in bankruptcy. Some managed with difficulty to carry out their agreement,

but on the expiry of their lease they quitted as ruined men, while others

failed to complete any more than half the terms of their contracts.

Big farms have therefore

proved a failure, and several causes can be assigned for this. The chief

cause may, however, be attributed to cost of production together with low

prices; because the big farmer when not near a town must employ a large

permanent staff, whereas in the days when he was surrounded by small tenants

and crofters he could secure labour just as he required it.

The landlords also made a

fatal mistake when they converted the small and middle class farms into

extensive holdings. No doubt they considered it more economical, as one set

of offices would serve where perhaps five or six steadings would be required

were the various farms to be re-let, the buildings of nearly all the smaller

farms being in a most dilapidated condition at that period. How far their

economical policy has benefitted them they themselves know; but now they are

compelled to sub-divide those farms its well as to erect premises and

offices; and thus it appears to have been simply a case of putting off the

evil day for a short period, and during that period the evil was

accumulating. Had the small farmers been left in their holdings 'they would

in all probability have weathered through the storm of depression.

CATTLE BREEDING

WITH the exception of a few

well-known herds, particularly in Ross-shire high class breeding of cattle

does not receive the amount of attention in the Highlands which the beef

producing counties of Aberdeen, Banff, Forfar, etc., devote to this branch.

Indeed, in these days, what with foreign competition and low prices, it does

not pay the trouble and risk involved in rearing fat stock.

The West Highland ox, with

his shaggy coat and picturesque appearance, is the breed most profitable and

best adapted to the Highland counties.

In 1884 Argyllshire alone had

660,500 head of best Highland cattle.

Sheep farming is an equally

if not more important industry than arable farming. In 1884 it was estimated

that in the Highlands there were 6,983,293 sheep, of which 2,393,826 were

lambs. The once remunerative business of sheep farming-induced landlords to

convert whole tracts of terri-tory, then under cultivation, into extensive

sheep runs; and sheep farmers are therefore looked upon. by the crofters of

Scotland as the primary movers or originators of evictions.

Sheep farming, as well as the

kindred branch of agriculture, has suffered in the general depression:.

aggravated by the large importations of foreign mutton and wool. The

estimated quantity of wool grown in Scotland in 1884 was about 34,500,004

lbs., and the estimated weight of wool imported from Australasia in the same

year was 400,000,000 lbs.

Again, the fabulous prices

offered for sporting estates led to the breaking up of sheep farms and the

converting of them into deer forests, so that to-day there are about 24

millions of acres occupied as deer forests in the Highlands of Scotland.

Before leaving the question

of sheep I must allude to the great "Wool Fair" held at Inverness, in July

of each year. There are hundreds of thousands of sheep sold annually at this

market, and yet not a head is exhibited. "This market is

peculiar," says a well-known

writer, "in so far as no stock whatever is shown, the buyer depending

entirely upon the integrity of the seller together with the character the

stock is known to possess." "It is a great source of pride to the farmers in

this. part of Scotland to be able, as they are, to say that no question

involving legal proceedings has ever yet arisen out of a misrepresentation

of stock sold at this market, which has been in existence since the

commencement almost of last century."

Dairy farming is not carried

on scientifically, nor to any great extent beyond the requirements of local

consumption, and only in a very few localitie's is cheese manufactured

beyond what is required for home use. There is wide scope for developing

this industry, for in many of the English counties the farmers are solely

dependent on the manufacture of cheese as the means of paying their rents.

[Co-Operative Dairies, with Central Creameries, have been established in

Ireland, and prove most remunerative investments. There is a wide field in

the Highlands for the. establishment of similar manufactories.]

On the rich alluvial lands

skirting the, shores of the Cromarty and Moray Firths, and indeed throughout

the Highlands generally, where farms attain an area of any considerable

extent, cultivation is carried out on the most improved principles; and

large sums of money have been expended on draining, trenching, and squaring

lands. The modern improvements in agricultural machinery have materially

assisted the farmer in bringing the soil to the present high condition in

which we find the arable lands in those districts referred to.

"No account of the

agriculture of Scotland," says the late sub-editor of the "North British

Agriculturist"—Mr. James Landells—"would be complete without some reference

to the peculiar condition of the smaller tenants of the Highlands and

Islands. The system of agriculture pursued by the crofters, or the smaller

tenants, is of the most wretched description."

The chronic state of poverty

associated with the crofting class is alluded to in an earlier chapter. The

land agitation, which had been smouldering over the Highlands during the

past fifteen years, at length broke out in the wild and distant township of

Valtos in Skye, and from there it spread rapidly all over the Highlands and

Islands.

It was not till 1882 that the

agitation reached its climax, when the "Battle of the Braes," near Portree,

began, where a force of seventy policemen arrested a number of crofters

accused of having deforced a Sheriff Officer; they were, however, all

acquitted, except two, who were fined. In the .autumn of same year another

campaign was commenced at Braes, and similar riots broke out in Glendale;

and the turbulent spirit was spreading all over Skye, until it was found

necessary to despatch H.M. gunboat "Jackal" with a special Government

Commission on board to remonstrate with the inhabitants. The agitation had

by now raised such a feeling in the country, and so attracted even the

attention of Parliament, that in 1883 the Government appointed a Royal

Commission to enquire into the condition of the crofters and cottars of the

Highlands and Islands of Scotland. The Commission, with Lord Napier as

chairman, found " that the crofter population suffered from undue

contraction of the area of holdings, insecurity of tenure, want of

compensation. for improvements, high rents, defective communications, and

withdrawal of the soil in connection with the purposes of sport." "Defects

in education and in the machinery of justice, and want of facilities for

emigration, also contributed to depress the condition of the people, while

the fishing population, who were identified with the farming class, were in

want of harbours, piers, boats, and tackle for deep-sea fishing, and access

to the great markets of consumption." The Highland Land League was now

organised; and at Martinmas, 1884, a "no-rent" manifesto was issued; and

many tenants absolutely refused to pay any rent until the land was fairly

divided among them. Raids were made on deer forests, march fences were

demolished, and lands were forcibly taken possession of, until the whole of

Skye and the Long Island were in A complete state of chaotic anarchy.

Attempts were made to serve summonses of removal, but the officers were

mobbed and deforced. In November, 1884, it became necessary to send a

military expedition to Skye with four gun boats and five hundred marines.

This formidable force restored order, and the crofters accused of acts of

deforcement submitted to be quietly apprehended.

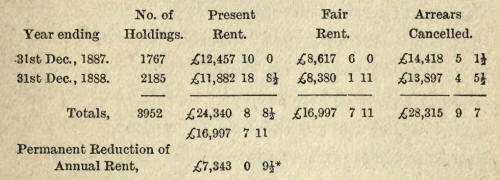

In face of the

recommendations contained in the report of the Royal Commission accentuated

by those riots in the Hebrides, Parliament in 1886 passed the Crofters'

Holdings (Scotland) Act, whereby three Commissioners were appointed to fix

"fair rents" and deal with the question of arrears, and at the end of year

1887 the Commissioners had examined 1767 holdings, and for year ending 31st

December, 1888, they examined and awarded decisions on 2185 holdings, being

a total of 3952 cases dealt with from the opening of the enquiry, having

7621 applications to be still dealt with as at 31st December, 1888.

I append a table showing

number of holdings for which "fair rents" have been fixed, and amount of

arrears cancelled.

* The total permanent

reductions in rent for the nine years 1886-87 to 1895-96 = £21,387 16s.—and

the amount of :arrears cancelled in same period = £123,469 2s. 10d.— Vide

Parliamentary Return, 6th April, 1897.

This gives an average

reduction of rent of 30.15 per cent, on the total number of cases examined,

and an average of 64.82 per cent. of cancelled arrears. These judicial

decisions prove that the crofters had just cause for complaint; and although

I shall not attempt to justify the means which they adopted for the purpose

of getting remedial legislation, still I will venture to say that our

legislators are pursuing a false policy in allowing bad laws to goad the

people to the verge of rebellion before they. introduce measures of reform;

for this gives an excitable race the idea that nothing for their benefit can

be obtained without becoming turbulent and riotous.

I have already shown that in

many parts of the. Highlands agriculture made rapid strides during the last

century; yet in the Hebrides, and,, indeed, among nearly the whole crofter

community, little if any progress has been made. In the first report issued

by the Crofters' Commission we find the following paragraphs:- "`The land,

both in Skye and in all the other islands visited, is subjected to a process

of continuous cropping which is disastrous. There is no particular shift or

rotation adopted, the land being continuously cropped. as long as it will

grow anything. The consequent waste and deterioration of the land,

especially the. weaker kinds, is enormous. This observation, however, is not

true to the same extent of Skye as of South and North list, the soil in Skye

being generally of a stronger nature."

"It may be added that in Skye

as in some other places we found great room for improvement in the matter of

leading drains. It frequently happened that a crofter suffered from his

neighbour, failing to make and keep these in a state of efficiency. - It

also frequently occurred that a crofter' waited for years on his landlord

getting such drains. scoured out in reliance on some real or supposed

obligation to do so, instead of putting them in working order himself and

thereby greatly improving his croft."

The Duke of Argyll, in a very

learned article in the "Nineteenth Century" of January, 1889, on

"Isolation," after deploring the alarming increase of the population on the

barren shores of the wild Hebrides, says:---"But there was another cause

that affected the whole of Scotland, where the rising tide of innovation and

improvement did not reach and did not submerge it. This cause was the

profound and almost unfathomable ignorance and. barbarism of the native

agriculture, together with. a traditional system of occupation, which, as it

were,, enshrined and encased every ancestral stupidity in an impenetrable

panoply of inveterate customs." This language may sound harsh, or even

unjust. And so it might be, if such language were not used. in the strictest

sense, and with a due application of the lessons to ourselves. We are all

stupid in our various degrees, and each generation of men wonders at the

blindness and stupidity of those who have gone before them. Alan only opens

his owlish eyes by gradual winks and blinks to the opportunities of nature

and to his own powers in relation to them. Let us just think, for example,

of the case of preserving grass in "silos," a resource only discovered, or,

at least, recognised, within the last few years, yet a resource which

supplied one essential want of agriculture in wet climates at no greater

cost of ingenuity or of trouble than digging a hole in the ground, covering

the fresh cut and wet material with sticks, and weighting it with stones."

"There is, however, something

almost mysterious in the helpless ignorance of Scottish rural customs up to

the middle of the last century. . . . In a country where there is a heavy

rainfall, its inhabitants never thought of artificial drainage. In a country

where the one great natural product was grass of exceptional richness and

comparatively long endurance, they never thought of saving a morsel of it in

the form of hay. In a country where even the poorest cereal could only grow

by careful -attention to early sowing, they never sowed till :a season which

postponed the harvest to a wet and stormy autumn. In a country where such

crops required every nourishment which the soil could afford to sustain

them, they were allowed to be choked with weeds, so that the weed crop was

heavier than the grain. . . . They sow corn as if they were feeding hens,

and plant potatoes as if they were dibbling beans. They think the more they

put in the more they will take out. In short, we have here a survival of the

wretched husbandry of the -lowest period of the military ages staring at us

in the fierce light of our own scientific and industrial times. "Without a

doubt, a great deal of the above is quite true; but then we know that

however impartial His Grace may try to be, yet his judgment must be more or

less biassed, as His Grace has anything but a favourable opinion of what he

calls "the worst of all native customs"—"crofter" townships.

"The whole of the outer

Hebrides," continues His Grace, "are mainly composed of the oldest, the

hardest, the most obdurate •rock existing in the world. It is the same rock

which -occupies a great area in Canada, on the north bank of the St.

Lawrence. The soil which gathers on it is generally poor, and even what is

comparatively good is often inaccessible. In its hollows, stagnant waters:

have slowly given growth to a vegetation of mosses, reeds, and stunted

willows. Gradually these have formed great masses and sheets of peat. Only

along the margin of the sea, where calcareous siliceous sands have mixed

with local deposits of clay, are there any areas of soil which even skill

and industry can make arable with success. The whole of the interior of the

island is one vast sheet of black and dreary bog. . . . To root them in.

that soil is to bury them in a bog—a bog physical,. a bog mental, and a bog

moral." So decides His Grace the Duke of Argyll; and yet Mr. Nimmo, one. of

the Commissioners appointed by the Government to enquire into the nature and

extent of the bogs in Ireland, in his report, issued in 1813, says: "I am

perfectly convinced, from all that I have seen, that any species of bog is,

by tillage and manure, capable of being converted into a soil fit for the

support of plants of every description; and, with due management, perhaps

the most fertile that can be submitted to the operations of the farmer.

Green crops—such as rape, cabbages, and turnips--may be raised with the

greatest success on firm bog, with no other manure than the ashes of the

same-soil. Permanent pastures may be formed on bog more productive than on

any other soil. Timber may be raised—especially firs, larch, spruce, and all

the aquatics—on the deep bog, and the plantations are fenced at little

expense; and with a due application of manure, every description of white

crops may be raised upon bog."

The expense of draining and

improving bog land, as estimated by Mr. Griffith, one of the Commissioners'

engineers, was about twenty-five shillings per acre, and he reckoned on

receiving an annual rent of thirty shillings per acre, on a lease of

twenty-one years.

Before the construction of

the Grand Canal from Dublin to the River Shannon, a portion of the Bog of

Allen, called the "Wet Bog," was originally valued to the promoters of the

Canal at one farthing per acre. It now lets for tillage and grazing at from

thirty shillings to forty shillings per acre.

I may be pardoned for

introducing this extraneous matter, as I wish to show the beneficial effect

arterial drainage would have on the swampy lands of the Highlands. Stagnant

waters produce one kind of unprofitable aquatic plants; vegetation is

affected by the quantity as well as the quality of the moisture which it

absorbs for its sustenance; and the cold, damp exhalations from the swampy

hollows have a most injurious effect on everything in their vicinity.

The draining of bog land in

Ireland has proved remunerative, and were the Government to do for the

Highlands and Islands of Scotland what they have on several occasions done

for Ireland in the way of drainage grants, and a complete scheme of arterial

drainage carried out in the Highlands, with a judicious planting of trees,

we should have a more fertile soil, a healthier and finer climate, a more

contented and industrious peasantry; and while the canals served as the

means of carrying off the superabundant waters, they could at the same time

be utilized as a waterway for the conveyance of the requirements of the

districts they penetrated, or used as a motive power for mills, which might

be erected along their banks.

'The method of letting farms

on long leases was, during prosperous years, considered one of the

distinguishing privileges of Scots farms, but in recent years matters have

entirely reversed. On the other hand, yearly tenancy has many objections.

The uncertainty of tenure tempts the farmer to take all he can out of the

soil while he has the opportunity; or perhaps, when he has exhausted or

impoverished the soil, he quits the holding. Of the two evils, therefore,

which is to be preferred, it is difficult to decide The most satisfactory

solution of the problem is the adoption of the principle embodied in the

Crofters' Holdings Act--security of tenure and rent fixed by a Commission.

FISHERIES

ANOTHER industry in the

Highlands of equal importance with agriculture is the sea fisheries. The

gross value of the sea fisheries of Scotland, according to the Fishery Board

returns for year 1887, amounted to £1,915,602 10s., of which sum £1,128,480

Ss. were accredited to the herring fishery. Tow, as the herring fishery is

chiefly confined to the Highland waters, it can be readily seen what an

enormous source of wealth this harvest of the sea yields to the country. The

means of employment it also gives to the surplus population of the Highlands

is very considerable, for no fewer than 49,221 men and boys were engaged in

the sea fisheries in the year 1866. In addition to this number, 50,973

persons were employed in connection with the summer herring fishery. The

estimated capital invested in boats, lines, nets, etc., is £1,712,349.

The herring fishery has gone

on increasing at an enormous rate since the year 1809, when the total number

of barrels cured was 90,185½; in 1850, the number increased to 544,009¼;

while in 1886 the number of barrels cured amounted to 1,103,424¼. Of this

aggregate quantity, 8605,911¼ barrels were, exported to Germany and other

places on the Continent; and a large proportion of the balance was sent to

America and to Ireland.

If it were not for this

industry, the Highlands —with its present low ebb in agricultural matters

--would be in a most deplorable state of starvation and misery; but the

All-wise Creator has compensated the poor Hebridean for his bleak and barren

land by providing a rich and inexhaustible -store in the precious treasures

of the mighty deep.

Although the fisheries of

Scotland have made ,extraordinary progress during the last fifty years,

-still there is much room for further development; ,and, to accomplish this,

several things are necessary. State aid must be given for the construction

of harbours and railways, [Since the above was written, the Government

granted :subsidies to the Highland Railway and West Highland Railway for

extensions of their systems.] and existing railway 'companies should be

compelled to carry fresh fish at a rate sufficient to pay them a fair

percentage for haulage, without swallowing up the entire profits of the

industry; a suitable and central station ought to be selected on the west

coast, where boats and steamers could land their cargoes so as to be

dispatched by the most rapid and economical route to the great consuming

centres of the Empire; and lastly, grants should be made to fishermen, on

favourable terms, for the proper equipment of the fishing fleet.

The restrictions surrounding

sums devoted by the Treasury under the Crofters' Holdings Act, have rendered

it next to impossible to apply the money for what it was intended; and

consequently-very few crofter fishermen have benefited therefrom.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF

THE FISHERIES

I APPEND the most interesting

statement made by Professor Ewart before a committee of the House of Lords,

in evidence for the proposed railway for the West Highlands, in March, 1889.

Professor Cossar Ewart, of

the Scottish Fishery Board, said "that great shoals of herring were to be

found all along the West of Scotland; and both inside and outside the Long

Island there were immense shoals. There were always large shoals running up

the coasts of Coll and Tiree. Many of them pass along between Skye and the

mainland into Lochs Hourn and Nevis, and others skirted the-outside of Skye.

There was a sort of concentration of herring shoals on +he inner coast of

Skye, especially upon the southern part. In 1882 there were cured from Lochs

bourn and Nevis no less. than 80,000 crans of herring. The fishing in the

following year did not prove quite so good, but there was no reason to

suppose that the number of fish had decreased. On the coast the number of

fish taken has enormously increased during the last fifty years; some years

as many as one million crans were taken. In his opinion it was impossible to

diminish by any means in our power the number of herrings on our coasts.

Even when the herring did not enter Lochs Hourn and Nevis they were to be

found in abundance in the vicinity; but the fishermen in the district were

not equipped in such .a way as enabled them to follow the fish, their boats

being too small and their gear insufficient. On the East Coast the fishermen

with their large boats scoured the whole of the north seas in search. of The

herring, going out as far as fifty or sixty miles; and they followed up the

shoals wherever they might go. The West Coast fishermen were an entirely

different class. Fishing had never been prosecuted by them in any systematic

manner. It is difficult to learn the trade of fishing; but the the men of

the West Coast were taking advantage of the example shown them by the East

Coast fishermen who had migrated there, and already there was a number of

very expert fishermen belonging to Stornoway and other centres. Hitherto,

except in certain cases, the fishermen of the West had received little

encouragement. They had been standing, if he might say so, with one foot on

the land and the other on the water, unable to make up their minds whether

to engage in fishing or to work their crops. He had known men who, after

having the necessary lines and hooks, had forsaken their resolutions to

become fishermen and, reverted to their crofts. The difficulty was that they

had no prospect of disposing of the fish with any profit .after they were

caught. Little was known about the white fish banks on the West Coast. He

knew, however, of a large bank lying to the north-west of Coll. The bank ran

up to Canna and outwards, and had a depth of from 11 to 50 fathoms. In

addition there were banks extending south-west towards Skerryvore and

Dhuiheartich Lighthouses. So famous, indeed, was this bank that East Coast

fishermen found it paid them to go round to Coll, build themselves huts, and

fish for cod and ling, which they dried and took home with them, or exported

to the Continent. Undoubtedly these men would prefer to have a market to

which they might send the fish in a fresh condition. The white fishing on

the West Coast had not been developed in the least, because as long as

herring paid well fishermen preferred to keep to that branch of the

industry. After suitable boats and gear, what the fishermen on the West

Coast required was ready and cheap access to the markets. The existing

railways of course performed valuable work, but there was a large district

between Strom Ferry and Oban. totally unprovided for. Roshven he regarded as

an extremely suitable place for a harbour connecting with a railway line. It

was convenient for all the-fishing grounds within the Hebrides, and it could

readily be reached from outside. The development of the fishing industry on

the West Coast was only a question of time. Already English fishing

schooners visited the Hebrides, and Irish vessels carne to Tiree. He had had

some experience of Norway, and he found that it cost less to convey herring

to London from Norway than from any part of Scotland.

"A scheme of co-operation

should also be organised by the fishermen, whereby they could establish a

central depot with a responsible agent in every ,large town. By these means

complete train loads of fresh fish might be despatched at cheaper rates than

by sending in driblets, and the various agents could keep the senders fully

apprised by telegrams of the demands of their respective markets."

TREE PLANTING

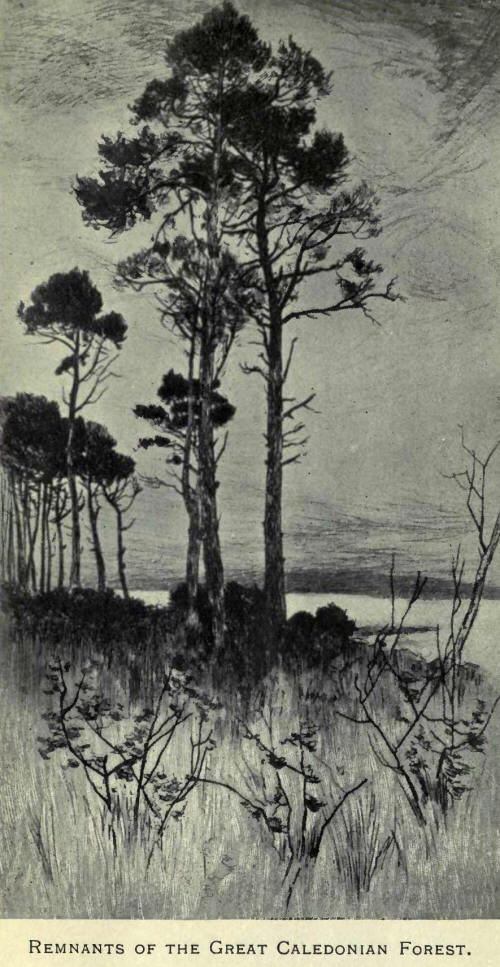

AT one period in the early

history of the Highlands the country was covered by vast tracts of pine

trees, and the remnants of these natural forests may be seen on mountain

-sides where solitary pine trees are dotted like stray sentinels on the

bleak crags of Glenorchy or buried in the deep morasses of Rannoch Moor.

The great forest of Caledonia

must have extended over many square miles of territory, and to-day large

areas of the country are covered by plantations of fir, oak, and other

trees, which take readily to the soil of our Northern Highlands.

The re-afforesting of the

Highlands is a matter which should engage the attention of Parliament: or

the Congested District Board, for, apart from the effect on the climate,

advantages are likely to accrue from sheltering bleak tracts of country and

affording cover for stock and game. The beautification of the country is no

small factor, but above and beyond all these considerations, there is the

possibility of a vast industry in the future, and the possibility of not

only supplying our home requirements in the way of timber for railway

sleepers and other industrial works, but, owing to the denuding of the

Norwegian and Swedish forests, it will be quite within the range of

probability that a large timber trade can be carried on with our colonies.

The nature of the soil in

nearly every portion of the Highlands is most admirably adapted for the

growth of pine, and from the slow growth of timber on our mountain sides,

the quality should even rival Baltic timbers.

There are thousands of acres

available for afforesting, land not suitable for cultivation or pastoral

purposes, but which could be profitably utilised for tree-planting. Again,

the vast amount of water power available in nearly every district of the

Highlands could be utilised in the manufacturing of the timber thus grown.

MANUFACTORIES

THE Highlands are singularly

destitute of manufactories, at least to any appreciable extent, for, with

the exception of a few wool mills and several distilleries, there is no

other branch of the manufacturing industry in the country. Shipbuilding was

at one period—before- ironclads were introduced--carried on in the

Highlands; and we find it recorded by Matthew Paris that, as far back as

1249, a magnificent vessel (Mavis Miranda) was specially built at Inverness

for the Earl of St. Pol and Bloise, to carry him with. Louis IX. of France

to the Holy Land. As far as Inverness is now concerned this industry is

extinct. I have not seen a vessel on the stocks for years. In so extensive

a, wool-growing country as the Highlands, with its unlimited source of

water-power, one would naturally expect to find the country studded with

woollen factories; but it is not so. Sir George Mackenzie, in his "Survey of

Ross and Cromarty, 1810," complains bitterly of the total. want of

encouragement by the inhabitants of the, country, and from the proprietors,

`in supporting a woollen manufactory started at Inverness by himself in

conjunction with other gentlemen, who thought the inhabitants of the

Highlands would eagerly encourage home industry.

About the beginning of this

century there were a good many woollen mills scattered over the Highlands;

but improved machinery caused the old-fashioned Band-loom to go the way of

the world, and they have fallen to decay, and neither sufficient energy nor

capital has arisen to replace them with modern machinery.

As an example of the decline

of the manufacturing industry, let us take the case of the Black. Isle,

where at this date not a factory of any description exists. [Through the

enterprising efforts of Mr. J. Douglas Fletcher of Rosebaugh, the Avoch

Woollen Mills have been recently equipped with new machinery, and a

considerable amount of business is now being done.] At Avoch, fifty years

ago, there was a large woollen mill in operation, and the manufacturing of

coarse linen from home-grown lint was carried on, and herring and salmon

nets and fishing tackle were extensively made, and several carding mills

were scattered over the peninsula. At Cromarty, less than eighty years ago,

"there was a mill for carding wool and jennies for spinning it; also a wauk-mill,

two flax mills, and a flour mill," . . . "a large brewery, and houses for

hemp manufactory. From the 5th January, 1807, to 5th January, 1808, there

were imported 185 tons of hemp, and about 10,000 pieces of bagging were sent

to London, which were valued at £25,000. During the same period were

exported .1550 casks and tubs containing 112 tons of pickled pork and hams,

and. 60 tons of dried cod-fish. There is also a ropework in operation, and

shipbuilding just begun." [Sir George E. Mackenzie's "Survey of Ross and

Cromarty, 1810."] To-day, I daresay, there is not another town of the size

of Cromarty in Scotland more destitute of commerce, nor more ,deserted. One

may well ask the question, whence this decay? It is simply isolation, and

what is here true of Cromarty and the Black Isle is also true of many other

isolated districts in the Highlands.

DISTILLERIES

THE most extensive industry

in the Highland is the distillation of whisky, and so enormous has the

demand been for Highland whisky that in the year 1851 the quantity of

spirits produced in Scotland amounted to 20,164,962: gallons, by far the

greater quantity of which was manufactured in the Highlands. In the year

1325, when the duty was reduced from 6s. 2d. to 2s. 4d. per imperial gallon,

the quantity distilled was only 4,324,322 gallons. The Government duty per

imperial gallon now is 106. 4d. per proof gallon. Smuggling or illicit

distilling is carried on to a considerable extent in the remote districts of

the Highlands at this very hour; and although the Revenue Officers make many

captures, yet the practice can never be suppressed so long as there is so

high a duty on whisky. By evading this high duty, the profit is so

remunerative as to tempt many a poverty-stricken crofter to venture the risk

of capture that he may be enabled to meet his obligations, and in many cases

he depends on the sale of his smuggled whisky for the money with which to

pay his rent.

Smuggling is an evil which

cannot be too much deprecated, for it not only demoralises the manufacturer,

but often leads to intemperance and immorality in communities that might

otherwise be sober and industrious.

KELP

THE manufacture of kelp at

the beginning of I last century was one of the most remunerative industries

ever established in the Highlands, and maritime proprietors have suffered

material loss from the abandonment of this manufacture.

The product of the alkaline

sea-weed was used in the manufacture of plate-glass and soap; but scientific

research discovered a cheaper substitute, which, together with the reduction

of duty on Spanish barilla, completely outworked the profitable production

of kelp in the Highlands. As a source of income it was enormous, especially

when the price ranged from £15 to £20 per ton; it, however, gradually

declined to £4 and £5 per ton, and now little if any kelp is made in

Scotland. I recollect seeing some burnt in Orkney about twenty years ago.

Lord Teignmouth, in his "Sketches of the Coasts and Islands of Scotland,"

states "that the number thrown out of employment by the failure of the kelp

manufacture—in a memorial prepared at Edinburgh, in the beginning of 1828,

by the proprietors of the western maritime estates----amounted to 50,000." |