|

Note: This is part of section IV of the

above mentioned publication.

The full text can be found

here in pdf format.

The Emigrant's Directory and Guide

To obtain lands and effect a settlement in the Canadas by Francis A.

Evans, Esq., Late Agent for the Eastern Townships to the legislature of

Lower Canada (1833)

HOW TO ASCERTAIN THE QUALITY OF LANDS.

Next to the choice of situation, that which concerns a settler, before he

should take any steps towards making a bargain, is to make himself

acquainted with the quality of the soil; for which let him remember, in

the first place, that when choosing land in a state of nature, he may

commonly know its quality by the Sort of timber growing thereon. Thus, a

mixture of all kinds of hard and soft wood, (that is, evergreens and such

as shed their leaves,) of a healthy growth, without too much underwood,

has a corresponding good soil fitted for most sorts of agricultural

productions. When the land is covered with firs or evergreen trees, called

soft wood, they indicate a poor sandy soil, which is by no means to be

recommended. The absence of all fir or soft wood, denotes a better

quality, and if there be no timber growing on it but maple and beech, the

soil is light and sandy. From a growth of large elm, maple, birch, oak,

walnut, beech, basswood, and some hemlock, with little underwood, may be

expected the best soil, if dry; but examination will satisfy the inquirer.

Large tracts of flat land are often met

with, covered mostly with tamarack or larch, where the upper soil is sandy

to the depth of from eight to twelve inches on a substratum of marly clay,

which, when cleared and drained is very durable and good, as deep

ploughing brings up the clay and fertilizes the surface. Emigrants,

however, seldom like to settle on such land, while the French Canadians

generally prefer it, the largest tracts of this quality being found in the

seigniories, near the St. Laurence, in Lower Canada. This sort is not

susceptible of such speedy cultivation as the former kinds, it being

generally necessary to drain it, and extract the roots of the trees,

before it can be ploughed or cultivated to advantage; while, on the other

hand, hardwood upland can be immediately cultivated the same year, after

having cleared off the timber, without extracting the roots; or even

beforehand, the crop often amply repaying the expense of clearing and

bringing it to that state.

DIRECTIONS RELATIVE TO THE OBTAINING OF LANDS -SECURING TITLES THEREIN

WITH SOME REMARKS ON THE SEVERAL KINDS OF TITLE, &C.

Government heretofore adopted various methods in settling the waste lands,

by several successive plans laid down for that purpose. A complement of

land was given gratis to every settler, on certain conditions of

settlement; but this is now no longer the case, as at present all the

crown lands are sold on easy terms of payment. Officers and discharged

soldiers, however, receive grants gratis, in the following proportions:-

Privates, 100 acres; sergeants, 200; sergeant-majors 300; Subalterns 500;

Captains 800; Majors 1000; and all higher officers 1200 acres.

It is thought the British Government were

led into the plan of selling land, from the comparative failure of the

several other plans that had been previously adopted, and from a hope that

such a system would tend to prevent the accumulation of large tracts in

the hands of unimproving individuals. Commissioners for the sale of crown

lands have been accordingly appointed in the several provinces, who keep

offices for this purpose at the Seats of Government where all persons may

purchase at a fixed rate, called "The upset price." There are also for the

same purpose in various parts of the country, Agents appointed by these

Commissioners. In several places, at certain periods of the year, "The

upset price" being fixed by Government, lands are set up for sale and

struck off to the highest bidder on any of the following conditions.-In

the first place, to such as pay the full price, they immediately get from

the Crown a direct title in free and common soccage for ever. Next, to

those who pay down one fourth of the purchase the three other parts in

annual instalments, free of interest: no right further than occupying it

is given, until the whole purchase money is paid; and the land, if not

paid for as agreed, may again be sold. Poor persons wanting 100 acres, or

less, may have the same by paying down one year's interest on the amount

of the purchase, and every other year doing the same till the principal

shall have been paid up; the land being liable to revert to the Crown, if

the interest be not punctually paid:-the purchaser may however, instead of

continuing the plan of paying this way, clear up what may be still unpaid

of the principal at any time convenient. Unless the whole of the purchase

money be paid, no person can sell or transfer lands thus obtained, without

the consent of Government, which is easily got if the parties wish, or

appear to act uprightly. The emigrant may be able to effect a purchase of

crown land on any of the conditions now mentioned, in Quebec, or in York,

on his arrival in either province, and choose such terms as will best suit

his views and circumstances, as the title obtained from tile crown is the

best that can be' procured. To these offices therefore the settler is

particularly referred, as by making himself there acquainted with the

terms and some other particulars, it will give him a general idea of the

value of lands in the several townships and their vicinities.

The prices of Crown lands for the current

year, (1832) in Lower Canada, in the townships open for sale, are as

follows-In the townships of Stanbridge and Dunham ten shillings per acre.

In Farnham, Stanstead, and Compton four shillings per acre. In Sutton,

Granby, Shefford, Milton, Potton, Barnston, Clifton, Hereford, Eaton,

Shipton, Windsor, Kingsey, Melbourne, Ely, Durham, and Upton, five

shillings. In Bolton, Westbury, Newport, Wickham, Ireland, Leeds, Hallifax,

and Inverness, four shillings. In Wendover, Caxton, &c. two shillings and

six-pence. In the townships on the Ottawa river, and south of Montreal,

five shillings. And in those of Stoneham and Tewkesbury, north of Quebec,

four shillings.

In other cases when the settler purchases

land from private individuals, or from proprietors on an extensive scale,

who are always met with in large towns, good titles may be had, but he

will do well to have proper legal advice as to the manner of sale,

security of title, &c. In the townships of Lower Canada, and in Upper

Canada, offices are established for the registry of any incumbrance

affecting real or landed property, and in such places secure titles may be

easily obtained; otherwise, great caution is requisite in persons who are

unacquainted with the laws and customs of the colony, as in a considerable

extent of the settled parts of Lower Canada it is difficult to procure

good or sufficiently secured titles to land.

Partially cleared lots which would make

desirable farms, may be had for ever in most settled parts; they can be

procured in more easily, and on cheaper terms, than wooded land could be

purchased for and afterwards cleared by a person who is a stranger to that

business, and are more desirable to the British farmer who, by availing

himself of such lots, would be at once able to settle and keep stock to

farm with, and thus be the sooner in the actual enjoyment of comforts, and

free from those inconveniences that are sometimes felt by those locating

in the woods. In many cases such farms with from ten to thirty acres or

more of cleared land, can be purchased for less money than wood land,

adding thereto the cost of clearing, being put into that state by persons

who prefer clearing to farming;, therefore to the settler who has got

sufficient money for that purpose, such farms would be an advantage if the

soil be good, on the contrary, if bad, the labour of clearing is thrown

away, and his circumstances become the most uncomfortable. Bad land being

harder to be cleared than good, which fulfils the old Yankee proverb, "it

is like a bad horse, hard to be caught, and when caught, good for

nothing."

Another method of obtaining land, of which

it may be necessary to apprise the settler, prevails in the Canadas.

Persons advanced in life are often met with, who, either not having

children, or having them already settled in life, desire to make their old

age comfortable without labour. They will give their farms, implements,

and stock, to an honest industrious person, who binds himself either to

support them during their lives, or else may pay them a certain rent for

the same term, upon the expiration of which, the tenant enjoys the whole

without further payment. In such cases, he will do well to be cautious,

and consult an honest lawyer on the form, conditions, &c. before he

involve himself in what, if not properly secured, may ultimately prove to

have been a severe burden. But if all things are found regular and fair,

the acquisition of a cleared farm and stock by this means, would be a

great advantage to the poor settler.

It is common also to rent farms for terms

of from one to seven years, longer leases not being frequently given; in

such cases the yearly rent is from seven shillings and six pence to

fifteen shillings per acre near the cities and large towns, and from five

to ten shillings at a distance of from ten to twenty miles. Cleared farms

are also frequently let on shares; that is, the owner of the farm stocks

it with horses, cattle, agricultural implements, and half the seed

necessary to be planted or sown; the tenant in return is to pay as rent

half of the whole increase of the stock produced on the farm; being bound

in all cases to cultivate it to advantage, and take all necessary care of

its fences, and of such other matters as may require to be attended to.

The Upper Canada Land Company, who have

agents in Quebec, Montreal, and various other parts, have vast quantities

of land scattered all over the upper province, besides the Huron Tract

already noticed, which consists of 1,000,000 acres near Lake Huron, 600

miles above Montreal. Their agents will be able to inform the emigrant of

their terms, and to show from surveys the various situations and lands to

be disposed of, the quality of the soil and all other particulars

connected with it, as well as the route to be taken by the purchaser. They

give titles of the land they dispose of, in free and common soccage for

ever.

The lands granted by the British

government, since the conquest of Canada from the French, which include

almost the whole of the upper and the townships in the lower province, are

granted in free and common soccage; by this tenure the owner is lord of

the soil, which is not liable to any rent or charge whatever, mines only

being reserved by the crown; and in this manner the land is sold and

transferred from one to another, subject to no condition or reservation

unless by mutual agreement.

In Lower Canada that tract along both banks

of the St. Laurence, from its mouth to Upper Canada, and extending back

from the river from ten to twenty miles or more, having been granted by

the French government before the conquest, is conceeded under a decription

of title not familiar to the British settler; it shall, therefore, be

described more particularly, as there are many desirable tracts of

seignorial land, very favourably situated near the St. Laurence, and

easily obtained. The substance of what follows on this head is taken from

a work on Canada, by Colonel Bouchette, Surveyor General.

The lands alluded to were conceded by the

French king in Seigniories, Fiefs, or Baronies, according to the Feudal

system. The Seignior holding the seigniory, fief, or barony, from the king

as lord paramount for public settlement, each seignior as he comes into

possession, and on the accession of a new sovereign, is obliged to do

homage and fealty for his seigniory, and on all transfers or sales of the

seigniory to pay to the king a quint or fifth part of the purchase, which,

if paid instanter, causes a reduction of two-thirds; so that in fact the

seignior was not much more than an agent to the king, to settle a portion

of the country, and receive certain emoluments for doing so and taking

care of the same. The seigniory is more or less in size from one to one

hundred square miles in surface. The Seigniors are by law obliged to

concede or lease lots, of about ninety acres each, of the seigniory to

tenants or censitaires on certain conditions that are easy: the tenant has

a lease for ever and pays for a lot from a halfpenny to a penny per acre

yearly, with other trifling considerations which come to about the same.

Latterly the seigniors have been charging more, whether legal or not, is

not so clearly, ascertained. The seignior has the exclusive right to the

grist mills on his seigniory, to which the tenants are obliged to give

employment, by using them when they have any thing in that way to get

ground the charge being one-fourteenth for grinding. Lands are also held

on leases of from twenty to fifty years or more, subject to a very small

rent, which titles are termed bail amphiteotique. Other lands are held by

what is called Franc allen, a freehold similar to what is called free and

common soccage, being exempt from all charges to any person but the king.

Another sort of title is called censive, subject to a yearly rent in money

or produce. All these that have been enumerated include the different

forms of title granted in the seigniories.

A most material privilege however belongs

to the seignior or landlord of the seigniory, which is called lods et

vente or part of the sales, being a twelfth part of the value of all farms

sold from one to another on his seigniory, which every purchaser must pay;

but a deduction of one-fourth is made for prompt payment. Thus, whenever a

farm on a seigniory is sold, the seignior claims a twelfth of its value,

which is a great draw back on industry; for if a person takes a lot worth

10£, and then expends on it 1190£, thereby making it worth 1200£, on the

sale thereof the seignior claims 100£, to which he can have no equitable

claim, though legal. Besides these privileges and emoluments to the

seignior, he has the right also of droit de retrait, which is, that he can

claim any farm sold by the tenant, within forty days after the sale, by

paying the highest price for the same. He can also claim a tithe of all

fish caught on the seigniory, besides being entitled to fell forest timber

any where on the same for his house, mills, roads, public works, and the

churches. Some seigniors have compounded for all their rights, unless lods

et vente, by receiving a greater yearly rent, that is, from fifteen to

twenty shillings per lot: The same remedy might be applied for lods et

vent: also, and thus have justice done to all, by charging a yearly rent;

and not suffering it to be as at present a tax on improvement. However,

when the land is not sold there is no lods et vents to pay, which is only

a grievance when a sale takes place. The French Canadians are generally

partial to the seignorial titles, perhaps from habit, and in consequence

of having them associated as they are with their laws and religion; the

Roman Catholics, who occupy farms in the seigniories, are obliged to pay a

tithe of one twenty-fifth, of all grain raised by them, to their own

clergy, besides assisting to build and repair their churches, parsonages,

&c. The seigniors to whom these seigniories belong, either live on them or

have resident agents, who are always ready to concede lands, and give

titles at once with scarcely any expense.

CURRENCY OR COIN CURRENT IN CANADA.

Before we proceed farther, it is necessary

to inform the stranger, that the pounds, shillings; and pence, in these

colonies, commonly called Halifax currency, are in value ten per cent

below the pounds, shillings, and pence, sterling. Thus 100£ sterling is

equivalent to 110£ currency. All the current gold, silver, and copper

coins of Europe and America pass here in that proportion of value. The

guinea and sovereign pass respectively for about twenty three shillings

and four pence, and twenty-two shillings, and some times more if the rate

of exchange is high on England; the dollar five shillings; the British

shilling one and a penny; the English and French crown five shillings and

six pence, and their several parts in proportion. In most places bargains

are made by the number of dollars, as four dollars make one pound, which

is a ready mode of calculating. It is hoped that this will not be

considered an irrelevant digression, as the emigrant who has not had

experience himself in these matter, must require to be taught by others in

order that he may find the less embarrassment in making such preliminary

arrangements as are necessary before he can proceed to occupy himself in

the more immediate works of agriculture.

SOME MATTERS TO BE PROVIDED ON PROCEEDING

TO SETTLE.

Having now endeavoured to give, in what I

conceived to be the most natural order, such directions and information so

that the emigrant cannot be at a loss how to conduct himself in any of the

preparatory steps to be taken, either in making choice of situation,

ascertaining the quality and properties of the soil, making a purchase, or

procuring a lease of a farm, and securing his title therein, I shall next

proceed to give such further hints as be may find useful, after all the

other arrangements shall have been fully made to his satisfaction; before

which, it may be no harm, in addition to what has been already said, again

to remind him that however good the quality of the land may be or eligible

its situation in other respects, it will nevertheless be of importance top

pay attention to the following particulars: Whether there be roads or

communications leading to, from, or near such lands; for if they do not

possess these indispensible conveniences he will find it a circumstance

attended with much trouble, as there should be a road at least within

three miles of him, if not more immediately contiguous. Whether they be in

the vicinity of, or have easy access to, a market of some kind, either

store, village, town, or city, as any one of them will generally answer

the generation that settle the land; grist and saw mills are equally

necessary, not forgetting the neighbourhood, neighbours, &c. And lastly,

but not of least importance, the security or validity of the title in the

land to be purchased. By paying due regard to these particulars, and

acting with discretion and prudence, he may proceed at once to his land,

and under the blessing of Divine Providence need not fear the result:

sobriety, industry, and perseverance, will be sure to crown his exertions

with the desired success.

In proceeding thus at length, after he has

surmounted all his preliminary troubles, to settle himself on his farm, he

will require to ascertain if provision can be got in its immediate

vicinity, if not to provide them in the most convenient place possible, as

it will be well to save the expense of carriage; otherwise he should buy

them in the town before starting. He should be also provided with suitable

axes for chopping, with strong hoes, a spade, grinding stone, pickaxe,

hand-saw, files, chissels, planes, a cross-cut saw, spoke-shave, hammers,

nails, hinges, locks, glass and putty. The axes, hoes, and grinding stone,

are what he will find necessary for clearing, but the other implements

will be found very convenient, as the settler will be able to do and get

done many useful and necessary jobs by being provided with them. Many, if

not all, of these articles may be got near the farm, especially the axes,

and if cheap it will be best to buy them there, otherwise to purchase them

where most convenient and cheapest. Loading, whether passengers or

luggage, will be conveyed for one penny a mile per cwt. land carriage, or

less, according to circumstances: French Canadians will cart cheaper than

any other, but the employed will remember to make the best bargain he can.

In travelling by land it is customary to carry provisions for the road;

and to stop at any farmer's house for refreshment, as public houses are

not always convenient on the different roads. It is in no wise recommended

to the settler of contracted means to buy horses for a new farm, on which

there is not much grass. A cow or two with a yoke of oxen (with a yoke and

chain to work and clear land) can be easily supported on brushwood, and

will live well in the woods, a few acres of which may be inclosed with

fallen trees, so as to prevent the cattle from straying away; but when

accustomed to get a handful of salt once or twice a week, they will always

return of their own accord; however a good cow-bell should be strapped

about the neck, to indicate, if necessary, where they may be found. Horned

cattle may be nearly supported during the winter also on hardwood tops and

brush wood. The following prices of cattle and articles are, what are

generally given at present in Canada; which will not be found, to differ

much in either province, unless when the size or breed make the

alteration: A much cow from 3£ to 5£; a working horse, from 7£ to 10£;

sheep from 7s. 6d. to 15s.; a yoke of oxen from 8£ to 12£; young pigs from

3s. to 4s., and, if six months old, from 10s to 15s.; a plough from 2£. to

3£.; an ass from 7s. 6d. to 10s., &c.; but from these rates there must be

often a deviation, as the season, place, and other circumstances, cause

the prices to be either below or above those mentioned. In all cases it

will be prudent for the settler to inquire concerning the value of such

articles in the neighbourhood where he is purchasing them, and to act

accordingly in making his bargain.

BUILDING.

A supply of such necessaries as the settler

may require being provided, a convenient lodging in the neighbourhood of

his farm, will be the best to procure until a log house can be erected. If

this cannot be provided, a log camp may be speedily erected in a few

hours, where a family can comfortably lodge for some time, and in which

(being built with logs and covered over with bark, split timber, boards,

or fir tops) more comfort will be found than expected, especially after

the confinement experienced by the emigrant on board ship. When this is

effected another camp may be erected in which to place his goods, and thus

he will find himself lodged at home on his own estate; which often gives

more real satisfaction than elegant and costly mansions do to the great.

Care should be taken that no large trees be left standing near the house

or camp, which in falling might reach it, as in consequence of having

their roots running near the surface they are liable to be laid prostrate

by a sudden gust of wind. It would be advisable for the settler, if he

have got the means, to employ a man accustomed to clear land for some

time, by which way he would in a short time become fully acquainted with

the business: or it would be well if he could contract for a job of three

or four acres to be cleared off, which generally costs from two to three

pounds per acre, the stumps of the trees being left in the ground, which

is not only the usual plan, but in fact the best and cheapest. This he

should get done round about the site of his intended buildings, which

ought to be in a dry situation, and near good water.

As soon as there is a sufficient space

cleared for building a log house on, straight logs may be got from the

timber cut down for clearing, or picked out up and down and drawn to the

building site:- the best timber for that purpose is pine, spruce, cedar,

hemlock, or fir; and if these cannot be got the straightest timber of any

other kind convenient. The log-house should not be longer than from

twenty-four to thirty feet at most, nor its breadth more than from twenty

to twenty-four feet; neither should the walls be raised more than ten or

twelve feet; for if the dimensions exceed these, as the logs decay they

will be apt to give out and fall. In general houses of this description

are not so large. Under the house should be dug out a good cellar, where

potatoes, and all such other provisions as may require this precaution,

could be preserved during winter from the frost, and in summer from the

heat. It will be found easier to do this before the house is built, and if

laid up with small logs, they will prevent the earth from falling in; the

cellar should not be within three feet of the breadth or length of the

house, and aught to be five or six feet deep, if the place can be

conveniently sunk so much. When a sufficient number of logs are provided,

the usual practice is for a few neighbours to assemble and assist the new

settler in laying up the walls of his house, each log being mortised half

way through at the angles for the cross one to rest in; and by this means

it becomes a firm building while the timbers last, which they may be

expected to do for about twenty years. On laying up the logs over the

parts intended for the doors and windows, notches are made large enough to

admit a saw, that when the walls are up there may be no trouble in sawing

them out to the proper size. When the rafters and ribs are set up, they

may be covered with shingles of split pine or spruce, or with boards, if

to be had near; but if these cannot be provided, the bark of elm, pine, or

spruce, may be easily peeled off in June or July, which makes a good

covering for a few years, and is again easily got and renewed. After the

house is covered in, if boards cannot be got, split basswood, fir, or

pine, is used for flooring, hewn smooth, and pinned to the sills or beams

of the floor. A house thus built, covered, and floored, may be got up for

about 10£. by contract, but will not cost half so much if the economical

plan here suggested be attended to; the owner will then have to finish it

off as may be convenient and suited to his taste. The usual practice is to

get small sashes and have them fitted in, a door hung on, stones collected

and a chimney built in one end of the house, moss and splinters of wood

stuffed well between the chinks of the logs, and plastered over with

mortar made of clay and sand; and after all this has been executed, the

house may be divided to suit the occupiers' comfort and wishes.

In such a house a family may live

comfortably, cheered by the gratifying reflection that they are residing

on their own estate, which will become more valuable every year, and for

which they have not to pay rent, taxes, nor any other of those charges,

which have been to them, while in their native country, a source of

perpetual uneasiness: where they can taste the sweets of freedom,

independence, serenity, and repose. At the approach of winter it will be

necessary to bank up the house with earth, about a foot high round the

foundation on the outside, in order to secure the cellar against frost,

and make the dwelling as warm as possible. In effecting these or other

local improvements, information and assistance may be always got from

those previously settled, who are ever found ready to contribute in every

possible way towards promoting the comforts of newcomer to the bush: a

fellow feeling that prevails, on such occasions, as well as a desire to

see their neighbours settled, causes all to interest themselves in the

welfare of the industrious new settler. A small pig or two may be

advantageously fed on the offal of the house, a yard being enclosed for

them, and the ensuing year they will be found to contribute to the

comforts of the family, after potatoes and other agricultural produce

shall have been raised. In parts where beech and oak grow, hogs feed and

fatten on the nuts and acorns, without any other assistance; but care

should be taken that they trespass not on the neighbours' crops. A few

fowls will also be a convenience, and are easily kept; it will be

necessary, however, to defend them from hawks, foxes, and any other

enemies to which they may be liable to fail a prey.

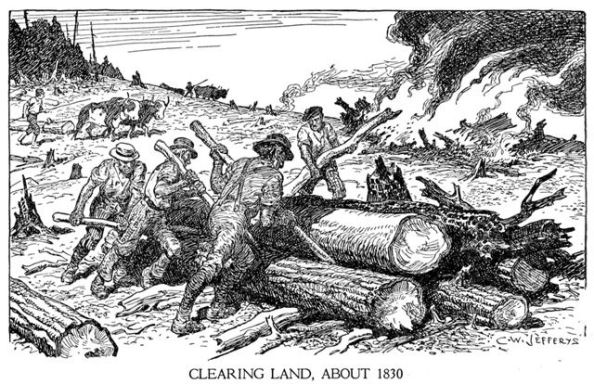

CLEARING LAND.

In clearing land to advantage, there is

need of much art and dexterity, and notwithstanding any directions that

may be given, a settler desirous of learning, will gain more by trying to

derive practical information from observing those who are well acquainted

with that business, than by volumes written on the theory. He is therefore

advised to observe for himself; or employ some person who has been brought

up in such work, or at least well acquainted with it; for, some will clear

an acre of land with one third of the labour that others have in doing so,

and labour saved in that way is as good as money saved. However, for the

information of the stranger, I will here add methods usually persued in

clearing, as he may not always find it easy to get such labourers as are

most profitable; and useful practical hints may occasionally prove

salutary.

A piece of dry land, or tolerably so, near

the house is the most, advisable to begin with. The most approved method

of clearing, especially if hardwood land, is to cut down the brushwood,

close to the ground, with a bush-hook or axe; in order to preserve the

edge, the blow should given up, but as close to the ground as possible,

that the stumps should not afterwards obstruct the harrowing. This should

be thrown in heaps, that when dry it may burn off the better, on burning

the other timber. When the brushwood is cut and piled on the piece

intended to be cleared, chopping down the large timber may be proceeded

with according to the following plan:- Observe to which side the tree

inclines, if to any, and on that side or near it chop in about two feet

from the ground; chop sloping dow, above, and straight in below, so as

that the stump shall be left quite flat. After having cut in more than

half way, minding to do it straight across, begin to cut on the opposite

side, about an inch or more higher than the former incision; and work in

as before, having one cut sloping down, and the other horizontal; when the

tree begins to crack or shake, it should be watched at each blow of the

axe, until you see it begin to fall; and then step one side, sufficiently

out of the way, as trees often bound, and are dangerous in falling. Care

should also be taken that it fall not upon another tree, as the getting it

down will be attended with some trouble and danger: dead, dry, or broken

limbs should also be watched lest they should fall on the chopper. Upright

trees may be made fall in any particular direction that may be desired, by

chopping first and deepest into the side at which it is required it should

fall; a little experience and observation, with presence of mind, caution,

and prudence, will only be necessary. When the tree is fallen the limbs

should be cut off into heaps, after which the body is to be cut up into

lengths of 10 or 12 feet; then take another and proceed in the same

manner, which will cause them not to interfere with one another. Six men

accustomed to this work, will, if diligent, chop about an acre in a day.

In about a month or six weeks, or sooner if in summer when the leaves are

on, the timber thus cut will be fit to burn, particularly if there be a

few dry days previous to firing it; it will be best to do so when there is

a light wind blowing from the buildings, and then the fire should be put

in the windy side of the field chopped down, and it will spread the better

among the fallen timber: it should be done about 10 or 12 o'clock in the

day. When the fierceness of the fire is past, the brands and small wood

may be thrown in heaps on the larger timber; and the heavy logs are

afterwards to be hauled together with oxen, or rolled with handspikes into

heaps, and burned off. As the piles are burned out, the ashes may be saved

for pot or pearl ash manufactories, being worth from six to ten shillings

per bushel for that purpose, if care be taken to preserve it from wet. The

land is then fit for planting or sowing in, and, if at a proper season,

the sooner the better after the fire becomes entirely extinguished.

Others again clear their land by first

chopping down the brushwood, leaving it scattered as it falls; after which

they cut down the large trees, and cut off the limbs, leaving them also

scattered as they fall, but do not chop up the body of the tree. When

sufficiently dry, it is set on fire as before, and let burn off; after

which, such logs as are not burned are chopped up, rolled or drawn

together in heaps, and burned off as already mentioned. When time or

labour is scarce in spring, many defer burning off the heavy timber, and

plant potatoes, Indian corn, or some other crops among the logs, which

answers very well when time does not admit of the land being wholly

cleared off, as when the crop is off in the fall the timber is easily

chopped and burned. The settler can pursue either plan, as both are

followed with success. He will of course perceive that what is meant by

clearing off the land does not include taking out the stumps of the trees;

as they rot out by degrees, and injure the land less by being left to do

so than by digging them out, a process in the course of which the poor

clay is drawn up to the surface: they will soon rot, and can be drawn out

or burned off with ease when dry. The stumps are very little in the way of

farming to advantage, as the ground may be ploughed and planted between

them without any difficulty, especially by a person accustomed to them;

their chief evil is the unsightly appearance they present to the eye of an

European, who is used to clear and level fields.

FENCING.

In clearing land, suitable timber may be

selected for fencing, and drawn or carried to the places where such

enclosures are to be made; but they should not be erected before the fire

is past, or it may burn them down again. Various methods of fencing are

resorted to, but if the place cleared be surrounded on all sides by the

woods, a row of trees felled one after the other, with such additions as

may be requisite, will be a sufficient temporary fence. When clearings

join the road or other clearings, a more regular fence will be requisite,

which is generally constructed on new lands, with logs cut twelve or

fourteen feet long, and about a foot or more thick; they are laid up

thus:- The largest are laid next the ground, lapping about a foot of each

end, side by side: some put a cross block under the lapped ends of the

logs, to raise them from the ground: on this row of logs is placed

another, with cross blocks under their ends, as under the first, and with

notches in the blocks for the end of the logs to lie in; and by again

laying on this another row of smaller logs as before, the fence is

completed, three rows high being generally sufficient, if the logs of

which they are composed be large. Some drive two stakes by each side of

every length of the Logs to cross at the top, on which they place long

heavy poles, to render the fence firm and strong. Others again lay up what

is called a zig-zag fence, which they construct with poles, and find to

answer very well; but the former will stand fifteen or twenty years and is

very firm. The settler may, as soon as he has got his land cleared please

himself by a choice of the many sorts of fencing used in the country; and

as good and firm ones are so very necessary to preserve the fruits of the

farmer's labour, he will do well to have his land sufficiently secured

that way, in order to guard against trespassers which would in a short

time ruin the prospects of a crop, if it were left at their mercy.

SOWING AND PLANTING NEW CLEARED LAND.

When the settler has a piece of land

cleared, he should not think of sowing wheat after the first of June,

although it is sometimes done in Lower Canada on new well burnt land, any

day during the first week of that month; the author himself had a good

crop of wheat which was not sowed till the eighth of June; but this should

not be depended on, and the earlier the better. Oats, barley, Indian corn,

beans, and rye, may be sowed on new land, the first ten days of June to

advantage, and potatoes may be planted all the month; but, as observed

before, the earlier the crops are put down, if the land be fit, the less

danger will there be of their being injured by the early frosts in autumn.

Wheat, rye, and peas require to be earliest sowed, and should be put in

ground as soon as ever it is free from frost in spring and fit in other

respects, but the above time is mentioned as the latest period for sowing

them. In such parts of new land as grain is to be sowed in, the piece

designed for that purpose should be harrowed among the stumps, in length

and across, with a harrow made like the letter A, and having nine large

teeth, two inches square, which should be drawn by the top by a strong

horse, or yoke of oxen; by this process the land is pulverized, and

considerably improved for receiving the seed. When this is done one bushel

of wheat, rye, or peas, will be sufficient for an acre, and of barley or

oats one and a half bushel. After sowing the seed, harrow the ground, well

as before, and should any remain uncovered, round stumps, or in any other

place out of the reach of the harrow, it may be covered in with a hand

hoe; many poor settlers, when they cannot procure harrows or oxen, hoe in

all their grain, and raise good crops. After it is harrowed in, it

requires no further labour till the crop is fit for cutting, unless to cut

down weeds or sprouts when they overtop it. With this cultivation wheat

will produce from ten to twenty five bushels or more per acre, but fifteen

is considered a fair return. Rye yields about the same produce, and will

do best in a light dry soil that may not answer for wheat; Oat, and Barley

from twenty to forty bushels per acre: Peas from ten to twenty bushels;

much of course depends on the care taken, the soil, season, and some other

accidental circumstances. Buckwheat may be sown about the last of June,

and will take about four gallons of seed to the acre; if it succeeds well

it will give a return of from thirty to fifty bushels.

After the smaller grain is sowed, Indian

corn, potatoes, and other vegetables, (unless those of the kitchen-garden,

which may be put down sooner,) depend the settler's attention. Indian corn

should be planted as soon as possible after the first of May, but may be

put later in new land than in old. After the ground has been harrowed, if

it be entirely cleared off, the planter having the seed in a small bag

tied round his, waist, commences the process of planting by striking his

hoe into the ground, raising the earth a little by lowering the handle,

and dropping in three, or four grains; then withdrawing the hoe, he takes

a step forward, treading down the earth on the seed, and striking it in

again about three feet from the former incision, so proceeds; the corn

being buried about two inches in the earth, and intervals of about three

feet being left between the rows and hills, it will require no other

attendance but weeding, until ripe. In every third or fourth hill or row,

two or three pumpkin seeds may be thrown in with the corn, as they grow

well with it, and when ripe are found very valuable to feed cattle or

hogs, the Americans also make good palatable pies of them. About a gallon

of Indian corn is sufficient to plant an acre, and if soaked in warm water

and copperas water, it will sprout the quicker; the copperas will also

have the effect of preventing vermin or birds from destroying it when

coming up. Some plant corn in new land, by scooping out a little earth

with the hoe, and, after they have dropped in the seed, cover it over in a

small hill; the former plan answers as well, and is done with much more

expedition. It will produce in a warm summer, from twenty to fifty bushels

per acre, and makes good bread or pudding, and is found a useful

ingredient in several other luxuries. It is a common thing to cut off the

tops a few inches above the ear or cob when it is full; which being dried

and carried home, make such fodder for cows, horses, and sheep, as they

are very fond of, and is, if well saved better than many sorts of hay. The

corn is ripe when the grain gets glazed in the ear, but must, when pulled,

be kept from lying too much in a heap, to prevent its growing mouldy. It

is usually gathered in September; the ears are broken off and thrown in

small heaps in the field; and as soon as convenient the husks are pulled

off, which may be done at night; after which the clean ears are spread

about six or eight inches deep on a dry loft or floor to dry and season.

Others make a crib two or three feet wide, and as long as may be

necessary, in which they put the cleaned ears of corn, and cover them in

to protect them from the wet; the air passing through hardens and dries

the grain. When hard it may be shelled, and if dry enough, ground up for

use; unless it be very dry will become mouldy when ground, if much be left

together; therefore the meal should be spread thin and loose in a box or

bin made for that purpose, else it will be soon unfit for use. Much then

of this should not be ground at once, unless extremely dry or kiln-dried.

Indian corn, besides being good for family

use, is good for fattening hogs, cattle, &c. and may, when ground, be

mixed with pumpkins or potatoes; the soft unripe ears are also picked out

at the time of harvest, and are excellent food for hogs, being thrown to

them without any further preparation:-in fact, Indian corn, when it

succeeds well, is one of the best productions of a new farm. The pumpkins

when the corn is being gathered, may be carted home, as they do not keep

well when, exposed to frost and thaws, and are therefore given to the

cattle and hogs in the fall or early in winter. Hogs fatten well on them

when cut up, and boiled and mixed with a little potatoes and meal; but

they may be given raw to the larger cattle, which are very fond of them:-a

great quantity will grow on an acre with the Indian corn.

Potatoes, the best root a farmer can raise,

and which are easily raised on a new farm, next demands the attention of

the settler. The quantity of seed required is about ten bushels to the

acre, the large round white potato being preferred. When the land, after

the burning off of the timber, is well harrowed according to the plan

already laid down, four or five cuts or seed ends are laid on the surface

of the ground, about six inches asunder, in a square; the earth is then

hoed up on them, forming a hill nearly as large as the contents of a

bushel measure emptied out; this plan is proceeded with, till the piece of

ground intended for that purpose be covered with these hills, which one

with another will occupy each about a yard square. Until fit to take up in

September, they will require to have no further labour expended on them,

unless weeding, which is seldom necessary. They are very easily taken out,

and may be deposited in small pits in the field, covered lightly with

earth, or put in the cellar of the house at once; otherwise, if wanted to

be kept till spring, they may be laid up in large pits, in a dry

situation, covered as usual with about two or three feet of earth, and

they will keep all the winter-but should not be opened till the April

following. They yield from two hundred to four hundred bushels per acre,

and the earlier planted after the middle, of May, the drier and better.

Turnips may be sowed in June or July in new

land, and require little attendance unless to thin or weed them: they

require to be lightly harrowed, and sowed before rain, and they will then

grow fast. Beets, carrots, parsnip, mangel wurzel and Swedish turnip,

require to be sowed earlier, and will do well-: all these must be sowed

broad cast, in new land. Melons, cucumbers, and other garden vegetables of

this description, grown in the open air, and are easily cultivated. French

or dwarf beans are planted in the same way as Indian corn, but not more

than one foot asunder, and are a very profitable crop for a family: the

white or mottled ones that do not run to vines are the best to plant, and

may be put down from the middle of May to the middle of June.

In saving crops of grain, potatoes, and

other vegetables, the same customs as in Europe may be followed, unless in

the additional care to prevent roots from the frost. The whole of the

crops in Canada when saved, are laid up in the barn, stable, root house,

or cellar. The Canadian farmers reap their corn greener than is generally

done in Europe, and spread it thin in the field as cut: after it has been

left lying for some days in fair weather, they bind it in large bundles

and carry it to their houses, which answers well in this country. They

also bind up their hay in bundles of fifteen pounds each, and sell these

by the hundred, equal to two thirds of a ton. It will be wisdom in the

settler to follow any good plan he may observe in useful operation among

persons long settled in the country, and so far as be is able, to improve

upon them; but not to make too much of a venture, until acquainted with

the climate and the country.

Such lands as are sowed with wheat, rye,

oats, or barley, should be laid down the first year with Timothy, or fox

tail grass seed or clover, and they will have a coat of grass for the next

year's use: the usual complement of seed for an acre is about two gallons

of grass with two pounds of red clover; but if the land be low or wet, two

pounds of red top grass seed will be sufficient for an acre without

clover. The grass seed may be mixed with the grain about to be sowed, and

all harrowed together, but others sow it when the grain is over the

ground, before rain; the former method however is preferred. Grass is

generally cut the latter end of July and the beginning of August, and in a

dry season, (as it usually is) is easily saved, put up in the barn, and

secured.

The settler should lay down in grass, each

year, the part he sows with grain, until he has his farm large enough; and

endeavour yearly to clear a sufficient extent for new crops; then in a few

years, what is first laid down in good heart will be fit to break up, and

most of the stumps will plough out.

In addition to what has been observed

respecting seasons it may be added, that in Upper Canada, and in the south

West parts of Lower Canada, the spring seasons are ten or fifteen days

longer than in the lower parts of this province, and the progress of

vegetation extremely rapid in all parts after the frost and snow depart.

Also for three hundred miles or more around Quebec, Montreal, or Kingston,

little difference is perceptible for or against the farmer in the settled

parts. The nearer the sea the deeper the snow lies in winter, and the

farther west the less snow or indeed frost; but always enough to prevent

vegetation, as when there is frost in Quebec it generally extends to the

utmost parts of Upper Canada, though it may not be so severe. During the

winter in the upper province, and to the south, there are many thaws

succeeded by frosts: in Lower Canada the season is more regular and

steady, but uniformly healthy and generally agreeable; and labouring men

can with little inconvenience work in the open air all seasons in the

year.

Having thus noticed the progress of

clearing and cultivating land on a new farm, it may be observed, that on

old cleared farms the same mode of farming as in the United Kingdoms may

be followed with success; subject only to such alterations as may be

necessary to suit the climate, secure the crops, and meet some other

contingencies: and also that fall or winter wheat and rye may be raised

well, though not usually done. As the hints contained in these pages are

not so much intended for the guidance of the farmer in farming, as of the

emigrant in settling, further observations on this head are deemed

unnecessary.

ON MAKING MAPLE SUGAR.

A branch of rural economy and comfort,

peculiar to North America, is necessary to be noticed for the information

of the emigrant, which is the manufacture of maple sugar. The settler

should examine his farm, and where he can get from 200 to 500 or more

maple trees together, and most convenient, that should be reserved for a

sugary. There being two kinds of maple, the hard and soft, the rock or

hard maple is the one to be preferred: both will make sugar, but this will

yield the sweetest sap and the brightest quality. If from among the trees

intended for this use the brushwood be cut down and removed, the business

can be carried on more conveniently. The process of sugar making is as

follows: As the sun gets power in the latter part of March, and beginning

of April, the sap begins to rise from the roots, and the trees are fit for

tapping: the sap continues, at intervals on fair days, to run for about a

month, until the sun gets too warm, and the buds swell out on the tree.

A large gouge or hollow chissel should be

provided, and a piece of dry pine or cedar got and cut into lengths of

about nine inches each. These pieces should be split into bolts, about an

inch thick, the breadth of the gouge; and these bolts again split up, with

the gouge, about a quarter of an inch thick, by which they will become

hollow spouts, like the instrument with which they are cut, for the sap to

run in: they should then be pared with a sharp knife at the end, to the

shape of the edge or point of the gouge, so that when it is driven half an

inch or so into the tree, the spout, also may be driven into the incision,

and fit it tightly. Troughs to receive the sap as it falls from the spout,

are made of pine, fir or ash, of a proper size, being about fifteen inches

through; such trees are cut up into lengths of two feet, which pieces

being split into two, each half piece is hollowed out with an axe so as to

contain about two gallons. A man accustomed to the work will make forty or

fifty troughs in a day, and they may be bought for about ten shillings per

hundred. Each tree of ordinary size will require one, and very large trees

two troughs. Those who can afford to get buckets instead of them will find

it an advantage, as much sap is thereby saved: they cost about ten pence

each. A tree will run about a bucket-full per day, on days succeeding

frosty nights with a moderately warm run to thaw the sap.

After all these have been prepared, one or

two of the troughs being placed under each tree, the person holding the

spouts, gouge and an axe, makes with the corner of the axe a small sloping

notch about an inch and a half long, and deep enough to penetrate into the

wood of the tree half an inch; the under side of the incision being cut

sloping down into the tree, so as that the sap may run to its lowest

point: if fit to tap, the sap is seen immediately, to ooze from the cut.

About an inch under that, the gouge is driven in for the spout as before

directed, through which the sap is conveyed down till it drops into the

bucket or trough at the foot of the tree, the cut being made almost two

feet from the ground: one man can thus tap about two hundred trees or more

in a day. Others for tapping are provided with an inch auger, with which

instead of making an incision with the axe, they bore a hole an inch deep,

and put in the spout an inch lower down as already directed: this though

more tedious is the best plan for the tree. One tapping generally answers

for a season, and the trees, if not greatly hacked, will do for a sugary

many years.

The sap is collected with a yoke and

handled buckets by a man every evening, or as the troughs get nearly full;

whence it is conveyed to the boiling place which should be a dry spot, -

the most central and convenient to the sugary. At the boiling place there

should be receivers, such as puncheons or barrels, to hold the sap until

boiled down; but when those cannot be got, large logs are hollowed out

with an axe for that purpose. The process of boiling the sap into sugar is

simple, and easily acquired: two stout crotches are fixed upright in the

ground eight or ten feet asunder, and on them is placed a cross stick from

which the pots or kettles are hung; a crook to hang them by being made of

a hooked piece of wood. The fire is made underneath of split or small wood

between two larger logs rolled on each side. The sap should be strained

into the boilers, and when boiling down, one boiler should be kept filled

from the other, and that again supplied from the receivers till the liquid

be boiled down to the consistency of sirrup. It is then taken up and

strained into a deep narrow vessel, there it is left to settle for a day

or two. When about being sugared off, it is carefully poured from the

sediment into a small boiler, and again hung over & slow fire; a little

milk, or a couple of eggs beat up, being put in to clarify it: as it

boils, it is skimmed, and after boiling about an hour to a proper

consistence, which is ascertained by practice and observation, it is

poured into vessels to cool, and stirred occasionally till cold. The

Canadians boil it so much, that when cold it forms hard solid cakes; to

make use of which, it becomes necessary to scrape it with a knife. It is

better, however, not to boil it so dry, but to pour it into a barrel after

boiling sufficently, and when cold, the sugar begins to crust on the

surface in a day or so; after which, by having a few gimlet holes bored in

the bottom of the barrel, the molasses will run off, and leave after it a

clean fair sugar, similar to, and better than, the best muscovado, and

more delicate in flavor- if care be taken in boiling, settling, straining

and cleansing. To prevent the sap or sirrup from boiling over, about an

inch square of fat pork should be thrown in once or twice a day, and it

will be found to have the desired effect. The scum, sediment, and last run

of the sap from the trees which is not good for suger, should be boiled

together one half down, and being barrelled, will by allowing it to

ferment, make good vinegar: it may be well, to put, in a little leaven or

yest, though it will answer without it. Each tree will average a produce

of about two pounds of sugar in the season, which extends to the end of

April. Two men will be able to attend from two hundred two five hundred

trees, and by attention will make good profit at a season, when they are

not wanted for other purposes; the sugar being worth from four pence to

seven pence halfpenny per pound. By a little examination and experience,

better than by any further direction, the settler may in a few days obtain

a perfect knowledge of the process; and if for a short time the labour be

found severe, the reward will be sweet.

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS ON ASHES, SALTS,

TIMBER, &C.

Before bringing to a close the observations

relative to the course an agriculturist is to pursue on newly cleared

land, a few other remarks are added, which may be conducive to his

advantage on settling in the woods. The first is respecting the ashes that

may be saved of the heavy hardwood timber burned on the land; the sorts

producing the best for pot or pearl ashes are, elm, maple, basswood, large

birch, and brown ash; the same use can be made of all others that can be

got, but these mentioned produce most and best. In order to keep it

uninjured, as before observed, from wet or damp, when the timber is

burned, the ashes should be collected and placed in a bin or safe; this

may be simply made of small logs, floored with logs or boards, and covered

over head from the rain. They should not be put in or near a house, lest

if put in hot they might burn the building; they have been known also to

take fire if vegetable oil be poured on cold ashes. In such a safe or bin,

as has described, they may be preserved until sold or otherwise disposed

of; therefore care should be taken to preserve all that can be collected,

as they are worth from six pence to one shilling per bushel, according to

the price of pot and pearl ashes; and if a fair price can be obtained for

them in this state, it is better for the settler to sell them than boil

them himself, as he is not accustomed to the process.

The older settlers manufacture their ashes,

for sale to the country merchants, into what is called the salts of lye,

when there are no purchasers convenient to buy them before taken through

any such process. To effect this, they provide themselves with two or more

deep tubs called leeches, which hold six or eight bushels of ashes, with a

spigot in the bottom; they are placed on a stand a foot or two from the

ground, with troughs underneath them to receive the lye when it runs off.

A few brick, stone, or a handful of brushwood, are put inside over the

spigot, on which is placed a little straw to prevent the ashes running

through or rendering muddy the lye: over this the dry ashes are poured,

nearly filling the leech, and gently pressed down; on which is poured

boiling water for the first run, that is, until with it the ashes be

perfectly soaked through: cold water may be then used until the strength

is all taken from the ashes, which is known when the lye running off is

weak like water. Two or more kettles, as in sugar making, are hung over a

fire to boil down the liquid that has run from the ashes, one boiler being

kept filled from the other, and that again filled from the lye running off

the ashes, until all gets boiled down to the consistence of tar, which,

when cold, it as hard or harder than pitch. This substance is called salts

of lye, and is the pot or pearl ashes in a crude state; it is readily

purchased by all Canadian country merchants, who have pot or pearl ash

works in which this is again manufactured by another process not necessary

here to be described. Salts of lye can be sold in the country, if not for

more, at least for one-half the price that pot or pearl ashes will fetch

in the ports or cities. The ashes saved from an acre of good hardwood land

will produce three or four, and in some cases five cwt. of salts which

sells this year (1831) at seventeen shillings and six pence per cwt. A

handy man will boil 1 cwt. in a day, and almost sixteen bushels of good

ashes will produce so much. This resource is a great advantage to the new

settler, as it affords him some cash for clearing off his land, by

producing an article for sale, which is always in demand, from what would

be otherwise thrown away as being of no use to newly cleared land. The

boiling place should be made near soft water if it can be conveniently

got.

On land where much pine, spruce, or cedar

is found, and not far from streams of water on which, when cut, it can be

floated, the settler can sell to lumber merchants such timber, being worth

when standing from one shilling to two and six pence per tree, according

to size, distance from market, &c; but in case he can sell them delivered

on the bank of the stream, it may be his advantage to do so, and thus earn

the more from his own labour and resources. I would by no means advise him

to attempt taking the timber to market himself, but leave that to those

who understand it and make that business their avocation; his object

should be to clear his land, make a farm, keep it in good order when

cleared, raise necessary provisions for himself and s much as he can for

sale, a succession of settlers always causing a demand for the necessaries

of life. When once he is independent, comfort is the result, if not his

own fault; nor need he long be deprived of the injuries attending

independence and freedom.

As settlers extend their farms, the demand

on the spot for the surplus of their produce naturally decreases in

proportion as provisions become more plentiful: the farmer then by degrees

may raise and fatten hogs, beef, sheep, and horses; which will carry

themselves to market, though at a great distance, and in the different

large towns and cities, or near the fisheries or ports, meet a ready sale.

Thus, in the beginning of his settlement the emigrant can save his ashes

and valuable timber for sale; as these decrease in the course of

cultivation, the produce of the farm will more than compensate for the

want: and in this manner much may be gained from the wilderness while he

is extending his farm for the good of the country, himself, and his

family; with a sure prospect of ultimate success.

CONCLUSION.

To attain this desired result with

satisfaction, industry, sobriety, and perseverance, only are necessary.

The country affords the materials, which only require to be acted upon;

protected as it is by a powerful state, in the enjoyment of civil and

religious liberty; and where the law affects no man for his opinions and

actions, unless so far as his conduct may be personally injurious to

public or private interests. As this is the case in the Canadas, it would

conduce much to preserve the blessing of public tranquility, if every

emigrant and settler coming to this country would lay aside all political

animosities and other intolerant feelings, and to live and let live in

mutual forbearance and christian charity; having a portion of that kindly

feeling for our fellow men, that the Most High has for all. With such

sentiments and a watchful care to preserve the public rights, supporting

the government in all its constitutional privileges; and discountenancing

every effort made to the contrary, they settler may live and enjoy himself

in comfort and happiness; the birth right of every peaceable and upright

British subject. Note: There is also

another publication on similar grounds at

http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com/~wjmartin/emig1822.htm also

done by Bill Martin. |