|

Among the Slag-heaps -

Within Sight of the Pentland Hills - The Macdonalds at the House of the

Stairs - I Cross the Boathouse Bridge - Sham-English Houses in Scotland -

I Arrive at Gray's Mill - The Edinburgh Comedy - A Scots Minister's House

on the Sabbath - The City from Arthur's Seat - The End of my journey.

THERE was a slight drizzle

of rain on that Sunday morning as I set out on the road to Edinburgh. I

did not know whether I would reach my destination before dark, but I was

determined to make the effort; and the prospect of sleeping in the city

which to my dying day I will think of as my home filled me with an elation

that made me ignore the rather uninteresting countryside through which at

the start I found myself passing. I had never tramped on this road before,

although I had gone quickly over it in a motor-car, and I had caught

glimpses of it from a railway compartment. I have always agreed with

Robert Louis Stevenson that there is no more vivid way of seeing a

landscape than from the window of a railway-train, to which must now be

added that of the motor-coach ; and while one does not travel merely to

gape at a picture-gallery of landscapes, and the delicate essences of

travel are distilled from many impressions other than those which enter

the soul through the eyes, travel of any kind would be a barren affair

without its visual background. But where the walker scores over the

railway-traveller is in this: his impressions may not be so quick or

sharp, but they have time to sink deeper, and they are enriched by a man's

contact with the ground over which his own feet carry him. The country I

met after Linlithgow is not picturesque in the sense that Blair Atholl is,

and only the blind can ignore the slag-heaps which the miners call "duff."

Back at Falkirk I had looked upon a land which gave me a fairly good idea

of what I had always imagined the Potteries to be like : the horizon had

been thick in smoke, with chimneys and the machinery of pit-heads looming

up through it in a ghostly way. East of Linlithgow the air was clearer,

but again the slag-heaps assault the eye; and as I passed beside them on

that Sunday morning I saw in them, almost against my will, a unique

beauty. Yellow grass grew upon them, and there was a curious red sheen

upon their dark sides, like the blood of an otter drifting a little below

the surface of a slow-running stream. Those pit-heads and slag-heaps of

West Lothian are a subject for an artist, but they need a man of the

calibre of Wadsworth to capture their spirit.

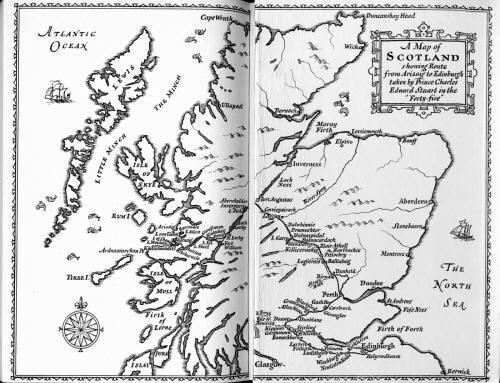

Soon I had passed

Kingscavil, and had come to a group of cottages called Three Miletown,

where the Prince brought his men to a halt. On the previous night, he had

managed to snatch but a few hours' sleep before making the sortie from

Callendar House at Falkirk, and now Lord George Murray was eager to push

further on, but Charles decided to remain until the next morning.

O'Sullivan had selected this place on rising ground, and the Prince slept

in a small farmhouse west of where the Highlanders lay in their plaids.

After I had passed through the hamlet of Winchburgh, which is unremarkable

except for the amount of dullness that is crammed into a few yards, I was

brought to a stop by the glorious view of a countryside that rolled to the

foot of the Pentlands. Caerketton and Allermuir, Swanston and Glencorse:

these names came back to me, bringing the same little wisp of nostalgia

that is always evoked by the name of the street in Edinburgh where I

lived, and in high spirits I strode out to Kirkliston.

It was near Kirkliston that

the Prince paused on the march next day. To the south-west was the house

of Newliston, then belonging to the Earl of Stair whose grandfather the

Highlanders blamed for the massacre of Glencoe. The descendant of the

murdered Macdonald chief was in the Prince's army with many of his

clansmen; and in sudden anxiety the Prince pictured the house of the

Stairs going up in flames, with the Macdonalds dancing vengefully around

it. He suggested therefore that the Glencoe men should be guided past the

place at a safe distance, but so indignant was the Macdonald leader that

he threatened to take his clan back to the Highlands if any watch was set

upon them. He reminded the Prince that the Macdonalds were men of honour,

and at once Charles responded by giving orders that a guard of Macdonalds

from Glencoe were to be mounted at Stair's house during the halt. The

Prince himself was entertained at the farmhouse of Todhall (afterwards

rebuilt and re-christened Foxhall by some man who was not satisfied with

the old Scots word for a fox); and in the afternoon the army moved forward

in the direction of Edinburgh.

I ate a late lunch in a

field by the roadside, and crossed the river Almond at the Boathouse

Bridge, when a sprinkling of rain again began to fall[. I was beginning to

fear I would arrive at the suburbs of Edinburgh too late to follow the

Prince's route round the city before darkness came; and so I seized upon

the rain as my excuse, and boarded a passing motorbus that was shining and

blue and incredibly luxurious. And like a lord among other silent lords

and ladies (whose tongues, I noted, were stricken with the same old

familiar Edinburgh palsy which arrests talk in the presence of strangers)

I rode into Corstorphine.

Old Corstorphine is

delightful, but God help new Corstorphine. Those recently built houses

scattered around the villages on the road from Stirling are enough to make

a man blaspheme: they are as ugly as the worst Victorian abortions;

indeed, I think they are even uglier, for many of the new ones are

shamEnglish. On an English countryside, they would have been bad enough,

but why in heaven's name must we have them in Scotland? If it is necessary

for economic reasons to build thousands of those little gimcrack things,

surely they can be designed in a way that does not strike the eye as

foreign. The old grey sombre Scots house, however small, has its own

beauty, and it should not be beyond the wit of a Scots architect to devise

an inexpensive house that is in keeping with the new spirit that is

arising in Scotland. Far worse than the red eruption of bungalows around

London are those sham-English blemishes on the face of many a Scots town ;

and as I drew near Edinburgh, I felt my ardour being soured with an angry

despair. Down to Slateford I made my way, passing the Stank which used to

be a loch, passing the place where Hailes House used to stand and where a

village was swept away to make room for a quarry, and coming at last to

Gray's Mill. Before me as I write, there is a map printed in 1654, and on

it this place is marked Kray, which suggests that the mill was not built

by a long forgotten miller named Gray, but was called after the estate on

which it stood. It is now the meeting-place of the Union Canal, the Water

of Leith, the railway to Glasgow, and a main road. These four channels

play an intricate game of leap-frog, and each emerges triumphantly intact

and rolls on to its destination. But there was only the road and the Water

of Leith going past Gray's Mill when the Prince took up his quarters on

the evening of Monday 16th September.

On the afternoon and night

of that day a comedy was enacted. Perhaps it would be more accurate to

call it a farce, and the scenes of it changed so rapidly that a modern

revolving-stage would be required for its presentation. The curtain had

been rung up for the Prologue about a fortnight before, when news had been

received in Edinburgh that Sir John Cope had failed to intercept the

Highlanders, and they were marching south. What was to be done ? Archibald

Stewart, the Lord Provost of the city, pulled in one direction, some of

the magistrates in another, and vague letters came from Whitehall to the

Lord Advocate telling him to do everything for the best, and to keep a

wary eye on the Lord Provost. As the Highlanders approached, there was a

babel of tongues in Edinburgh, and the voices of the few men who were

ready to die in defence of the city were drowned in the caterwaul.

Gardiner's dragoons, covered with foam if not with glory, had scuttled

from Linlithgow and were now with Hamilton's dragoons at Coltbridge. Some

of the dashing cavalrymen supported by a few Edinburgh volunteers ventured

to go out towards Corstorphine, where an advance guard of the Highland

army saw them and fired a few shots. The scouts hurried back to Coltbridge

and breathlessly announced that the rebels were upon them. This was too

much for the stomachs of the dragoons : in a panic they went

hell-for-leather by the lanes through Bearford's Parks and the Lang Dykes

and did not draw bridle until they were safely on the links at Leith. This

"Canter of Coltbridge" was watched from the Castle. It took place at three

o'clock on Monday afternoon, and Edinburgh was left undefended except by

the untrained rabble of citizens, students, and apprentices who manned the

broken city wall.

That morning, between ten

and eleven o'clock, an Edinburgh man called Alves had ridden into the town

the Prince's army on the road, and the Duke of Perth had asked him to say

that if they were allowed to enter Edinburgh in peace the citizens would

be dealt with civilly. From Corstorphine, the Prince had sent to the

magistrates a formal letter summoning them to surrender the town; and at

Gray's Mill, about eight o'clock in the evening, a deputation waited upon

him.

It was well known in

Edinburgh that Cope's army was on its way by sea from Aberdeen. For days

the weather-vanes of the city had been anxiously watched by the Whigs to

see if the transports had a fair wind to bring them south. And the four

bailies of the deputation, in an awkward group at Gray's Mill, did their

best to look innocent of guile, and begged for a little delay. The Prince

replied quite simply that he demanded to be received as the son and

representative of the king, and that he expected an answer by two o'clock

in the morning. Half an hour after two o'clock a second deputation turned

up at the Mill with a fatuous message to the effect that the citizens of

Edinburgh were now snugly in bed, where all good citizens should be, and

so their views about surrendering the city could not be obtained until

morning. The Prince, urged by Lord George Murray, saw the deputies ; and

after he repeated his demand to be received as the Regent of the kingdom,

the members of the deputation trundled back in their hackney-coach. It

would have been clear to a half-wit that the magistrates were playing for

time, and Charles had already ordered Locheil with nine hundred men to try

to take the city by surprise, and if necessary to blow up one of the

gates, but to avoid bloodshed as far as possible. Guided by John Murray of

Broughton, who knew the district, Locheil made his way to the Netherbow

Port and sent forward one of his men disguised in, a riding-coat to

pretend that he was a servant of an officer in the dragoons, but he failed

to get past the guards at the gate. Locheil drew off, when to his

surprise, the Netherbow Port was opened, and the hackney-coach which had

taken the last deputation back to the city came clattering out to return

to the stables in the Canongate. The Highlanders rushed in. Dawn broke as

the capital of Scotland surrendered. It was said at the time that half of

the folk were Jacobites at heart : one-third of the men, two-thirds of the

women.

During the night at Gray's

Mill, the Prince slept for a couple of hours in his clothes; and sending

the heavy baggage past Morton Hall by a road south of the Braid Hills, he

led his army along the lane that crossed Caanan Muir, near the ruins of

the ancient chapel of St. Roque, out of sight of the Castle guns.

Before leaving Gray's Mill

on that Sunday afternoon, I went forward to the door of the little house

and knocked. I would have liked to see where the Prince spent the night

before entering Edinburgh, but to my repeated knocking there was no reply

; and I made my way down a side-road to Craiglockhart, passed the

Poorhouses, and came out upon the Morningside road. The name of the moor

over which the Prince marched still survives in Caanan Lane, and I walked

past Grange House, where the Prince paused to drink wine with William

Dick, " the third baron, and Anne Seton his lady," and to leave behind him

a thistle from his bonnet in exchange for the white rose Anne Seton gave

him when she kissed his hand.

I turned into Dalrymple

Crescent. There was a gentle thrill in the thought that the house where I

had spent so many years of my boyhood stood within a stone's throw of the

Prince's line of march, and it made my journey on that last day the

sweeter. When I saw Edinburgh again that evening, I was thankful I had

lived there and had memories to play with. Folk were going to church, and

the sight of them brought back all the strange salt flavour of an

Edinburgh Sabbath : the bustle of a minister's house on a Sunday morning;

an hour's silence while my father had a final glance at his sermon; the

manse pew in the gloomy church; Old Hundred and other tunes that wove

themselves into the fabric of my mind; cold midday dinner; the church

again at half-past two; Sunday school; late tea and "a good improving book

"-with luck, Treasure Island-then a tramp to the Blackford Hill, and bed

at ten. A strange sombre day, as I look back on it; and yet on that

evening as I passed the old house in the Crescent, I would not have

changed a single hour of it for anything in the world.

By Salisbury Road I went,

and down to the King's Park. The Prince's army had passed through the

policies of Prestonfield House, and by a gap in the wall had gone round to

Duddingston, to climb the hill by Dunsappie Loch. In the Hunter's Bog, a

shallow glen behind the Salisbury Crags, the Jacobite army bivouacked, and

the Prince left them at noon to go down to the Palace where Mary Queen of

Scots had spent so many of her days in Scotland, and where the Prince's

grandfather had made himself popular with the nation when he was the Duke

of York. Near St. Anthony's Well on the hillside, Prince Charles paused

for a few minutes and stood looking across at the city on its ridge of

rock. He knew he had come to the first stage in his campaign to recover

the British throne for his family. The capital of Scotland was at his

feet, but he knew that Cope's army had landed at Dunbar and was marching

to meet him. He knew how much depended upon himself; he had already seen

how delicate was to be the task of keeping the peace in his own camp. In

his hour of triumph, his thoughts were heavy as he descended to the Palace

of Holyroodhouse. On the hillside I sat down. The darkness was falling

quickly. Deep shadows lay in the valley, and my eye travelled to the

skyline of housetops and church-spires and the failing sunset above. I

thought of the Prince as I sat there, and the long journey he had made

from Borrodale in Arisaig. I recalled the stages of that journey, the

roads and the hill-tracks by which I had travelled over the royal road,

and the inns and cottages where I had slept, and the people I had met and

talked with, and the ups and downs of fortune that make a long journey on

foot so like the varied span of a human life. Had the Prince's road been

worth my travelling over, I asked myself, and out of a thankful heart I

was able to answer. I rose to my feet. My pack seemed to have become

lighter, and I was deliciously tired and hungry. At Abbeyhill I sank down

on the seat of a taxi-cab: it was good to hear an Edinburgh voice again!

Fifteen minutes later, I was in Abercromby Place at the doorway of the

Royal Scots Club.

In later volumes the author

will describe his subsequent travels in the footsteps of Prince Charlie. |