|

One of the first operations resolved upon by the

Court of Directors of the Darien Company was the organising of a banking

business as an adjunct to their great colonisation scheme. This was in

defiance of the Act passed in favour of the Bank of Scotland on 17th July

1695, whereby that institution had a monopoly of banking in Scotland. The

Bank Act declared that, for the space of twenty - one years after its date,

"it shall not be leisom [lawful] to any other persons to enter into or set

up an distinct Company of Bank within the Kingdom."

The Act of the Darien Company contained no

reference to banking, being solely directed to foreign trade and commerce.

It appears, however, that Paterson had it in view from the first to include

banking, or a "fund of credit" as he termed it, as part of his scheme. This

intention was kept secret at first; but it got "air" about the month of May

1696, while Mr John Holland of London, the founder and first governor of the

Bank of Scotland, was temporarily residing in Edinburgh. Holland had come to

Scotland at the request of the directors of the Bank for the purpose of

placing the young institution on a proper business footing, as he was

thought to be better acquainted with the nature and management of a bank.

Holland felt keenly the unexpected and hostile attitude of the Darien

Company, and he made a spirited attack on Paterson in a pamphlet published

in Edinburgh in 1696. This brochure is entitled 'A short Discourse on the

present Temper of the Nation with respect to the Indian and African Company

and of the Bank of Scotland; also of Mr Paterson's pretended Fund of

Credit.' In this paper Holland stated that, on his arrival in Edinburgh,

Paterson came " and begged him to pardon his ever pretending against the

Bank, and [declaring] that whatever had been [done] was only for fear it

might interrupt and hinder the subscriptions to the African Company, but he

[Paterson] saw it did not, and therefore wished all manner of success to

it." [Paterson had no hand in the formation of the Bank of Scotland, but was

rather opposed to it. In a letter to Lord Provost Chiesly, dated London,

15th August 1695, he says, "I desire a copy of the Bank Act so

surreptitiously gained. It may be a great prejudice [to our Company], but is

never likely to be any matter of good to us, nor to those who have

it."] Notwithstanding this protestation, Paterson and his associates

proceeded with their banking operations.

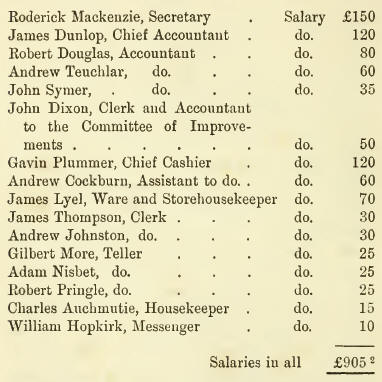

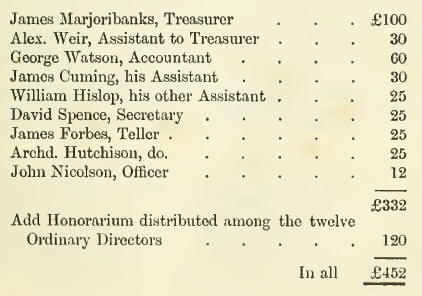

The following establishment was appointed,

apparently with a view to engaging in banking on an extensive scale:—

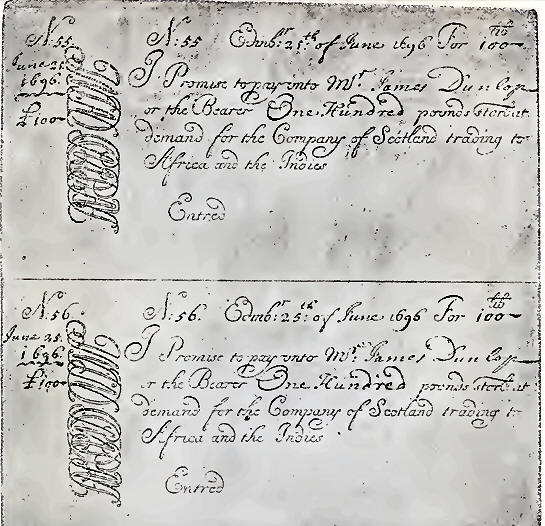

On 18th June 1696 an engraved copperplate for

printing bank notes was given in charge by the Court of Directors to their

Committee of Treasury, "to be kept under lock and key with the cash." The

committee were also ordered to take care " that no copies or blank bills

should be cast off or printed, but in presence of three at least of their

number; who were further directed to take all such blanks into their special

care, as if the same were real money."

A writer in the ' Scottish Antiquary' of July

1896 states that the character of the lettering on the copperplate is so

close a copy of Paterson's handwriting that it may be assumed that the

original model of it passed to the engraver

direct from his own pen. A similar reference is made to the handwriting

filling up the blank spaces, dates of issue and money amounts, &c., of the

actual notes in process of being made ready for circulation.1 The

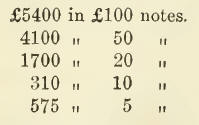

notes were of the values of £100, £50, £20, £10, and £5. The same

copperplate was used for all the denominations of the notes, the different

values being written in with the hand.

Following upon this—viz., on 26th June— the

Court of Directors, having under consideration " the manner of rendering the

Company's Current-Bills useful," ordered that fit persons should be

appointed at Glasgow, Dundee, Aberdeen, &c., to be cashiers to the Company,

who should have certain amounts of the Company's bills in their hands, to

answer and serve the Company's correspondence in these towns and the several

next adjacent places. Accordingly, the cashiers of the Company in the

various parts were charged with the Company's bank notes, for the purposes

of circulation, as follows :—

Owing to the poverty of Scotland at this period,

the practice of receiving money on deposit had not begun, and banking

clients were all borrowers. [The Bank of Scotland appears to have first

received money on deposit in 1707, for which no interest was given. In 1729

it was received on current account on the treasurer's bond or bill, carrying

interest. In 1762 notes payable to order by the treasurer for deposits began

to be used as a regular branch of business. In 1810 deposit receipts were

commenced, and havo since continued in use.] Strict banking consisted in

lending money on heritable and personal bonds and in the discount of bills.

By this means the Bank notes were placed in the hands of the public.

As we have seen, the Darien Company opened

agencies in various provincial towns for the purpose of circulating their

notes. This infringement of the Bank's special Act of Parliament and

obstruction to its progress at the beginning of its career was very trying

to the young institution. In a letter written in 1696 by the London

directors of the Bank to their colleague Mr Holland in Edinburgh, they say

that they "are sorry to hear of any designs of the African Company against

us [i.e., the Bank], having resolved to assist them in the best of our

power, they themselves within the bounds of their Act." Although the Bank

directors possessed the exclusive privilege of banking in Scotland, they did

not exercise their right of contesting their legal position, and so

extinguishing the innovation on their monopoly. The Darien Company was too

popular throughout Scotland, "the whole humour of the nation being run on

it," to render any action of this kind a success. The Earl of Marchmont,

writing to the Duke of Queensberry in December 1699, says: " I have enough

ado to keep myself from falling into disgrace with that Company, which is

little less than to say falling into disgrace with the Scots nation." Mr

Holland noted this, and prudently advised his fellow-directors "to lie by

for a little, and so manage the Bank's affairs as not to suffer an affront

from the mighty Company by the latter making a run upon their cash." As it

happened, the obstruction was temporary only, and in a year or two it

entirely disappeared.

Lawson, in his ' History of Banking,' states

that in order to obtain a circulation of their notes, and to suppress the

notes of their rival the young Bank, the Company lent money on securities

which they were unable to realise, —"this coming to the knowledge of the

public, lessened the value of their stock so much that they ultimately gave

up the banking business." The Company also made advances to their own

proprietors on the security of their stock—a practice which had to be

discontinued. [ "And the Committee of Treasury was ordered to sign no more

Warrants to the Cashier for lending money to any of the proprietors of this

joint-stock, upon the credit of their respective Shares therein, without

special order from the Court of Directors concerning the same."—Darien

Company Minute, 2nd October 1696.]Probably the chief cause of their

non-success in banking was the fact that the whole of their paid-up capital,

with borrowed money in addition, was fully required in exploiting their

great colonisation scheme. The want of "till-money" endangered the

convertibility of their notes. As Paterson himself states in a tract,

published in 1705, "No bank can succeed without a considerable fund of cash

to answer necessary demands."

When the notes were finally retired by the

Company on 19th June 1701, the total issue had amounted to £12,085 only,

thus—

These notes were the Company's first and only

issuer They were all dated 25tli June 1696; made payable to the chief

accountant, James Dunlop, or bearer on demand; signed by the chief cashier,

Gavin Plummer, and countersigned as "entered" by the assistant cashier,

Andrew Cockburn. The Company had no notes below £5. [By way of contrast, we

give the Bank of Scotland note circulation at the time. In his 'Short

Discourse' (1696) Mr Holland says: "As soon as the rules and methods for

carrying on the Bank of Scotland were agreed to by the General Meeting of

Adventurers, the Directors proceeded to business, and with such success that

the credit of the Bills [Bank notes], as fast as they were issued out,

obtained to a degree beyond expectation." The Bank took in its subscriptions

and commenced business some months earlier than the Darien Company, and

their first issue of large notes is dated 25th March 1696, being three

months prior to those of the Darien Company. £1 notes were not issued by the

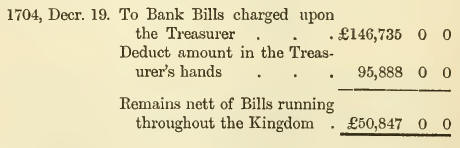

Bank until 7th April 1704. In December 1704, when the Bank made a temporary

stop, caused by the scarcity of money all over the kingdom and by a report

that the Privy Council was to cry up the value of "species," the

balance-sheet, drawn up for the information of the Council, reported that

the Bank notes outstanding amounted to £50,847. This was after the Bank had

met a severe run.

|