|

THE Castle Hill, on which

the Esplanade and parade-ground are formed, was the scene of many

horrible executions of unfortunate persons found guilty, in the ignorant

intolerance of the times, of witchcraft and heresy. On one occasion no

fewer than five suffered together the agony of being burnt at the stake.

They were: Thomas Forret, Vicar of Dollar, John Keillor and John

Beveridge, both Black Friars, a priest of the name of Duncan Simpson}

and Robert Forrester, a gentleman. It will be remembered that King James

V journeyed from Linlithgow to witness this revolting spectacle, an act

that could hardly have been expected from a monarch who had done so much

for social reform.

Punishments for

witchcraft were frequent. Great numbers of wretched, ignorant creatures

of both sexes and of various conditions were accused of this imaginary

crime and put to death with the most horrible tortures.

Sorcery was treated as a

criminal offence as far back as the reign of James III, when his

brother, the Earl of Mar, along with twelve women and three or four

others who were supposed to be accomplices, was burnt to death for

consulting with witches upon a plan to shorten the life of the King. It

is not until the reign of Queen Mary that a proper trial for the crime

aj pears on the records of the Justiciary Court. In Mary’s ninth

Parliament we find an Act passed declaring that witches or consulters

with witches should be punished with death, which Act became operative

immediately. Persons of high rank maliciously accused others in society

of this imaginary practice. The Countess of Atholl, Lady Buccleuch, and

the wife of the Chancellor, among others, were openly charged with

dealing in charms and protecting witches. Even John Knox, the great

reformer, did not escape the accusation of having attempted to raise u

some sanctes in the kirkyard of St. Andrew’s,” and it was said that

whilst in the midst of his incantations he raised cold Nick’ himself,

with a great pair of horns on his head, a sight so terrible that Knox’s

secretary died from fright.

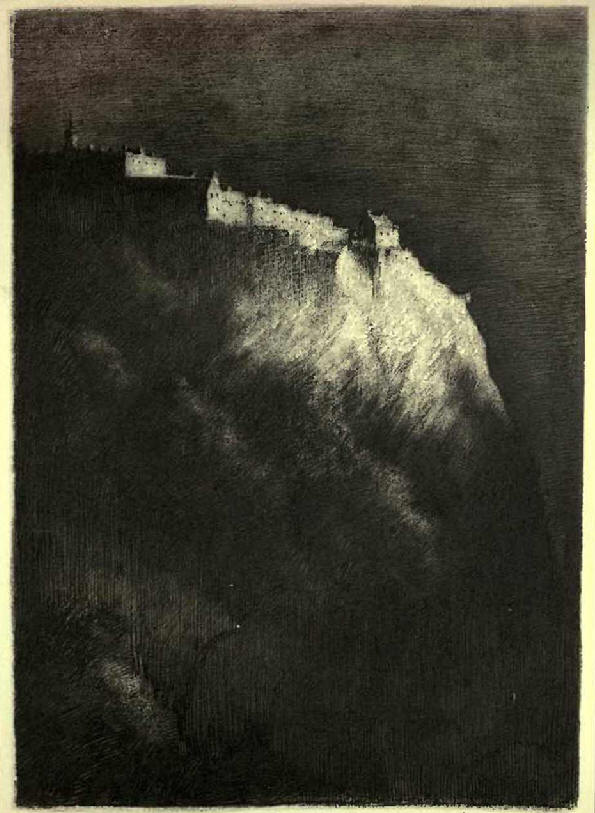

CASTLE BY MOONLIGHT

A terrible fate befell

Dame Euphemia Macalzean, Lord Cliftonhall’s daughter. She seems to have

been a lady of powerful intellect and licentious passions, and was not

only accused of many acts of sorcery of a common kind, but was also

charged with complicity in the making of a waxen figure of the King, and

with conspiring to raise a storm to drown the Queen on her homeward

voyage from Denmark. A great number of poisonings and attempts at

poisoning were also included in her indictment, but the jury acquitted

her in respect of several of these alleged crimes. She was found guilty,

however, of destroying by witchcraft her husband’s nephew, Douglas of

Pumfraston, and of attempting to destroy her father-in-law, as well as

of participating in the practices against the King’s life. The

unfortunate lady was an adherent of the Romish faith and a friend of the

turbulent Earl of Bothwell, who also was alleged to have been implicated

in the matter of the waxen figure and in other similar devices against

the King. Her punishment was the severest the court could pronounce. She

was condemned to be u bound to a stake, and burnt in assis, quick

[alive] to the death,” and all her estates and property were forfeited

to the Crown. She endured her horrible fate with the greatest firmness

on the Castle Hill, June 25, 1591.

These trials produced a

deep and permanent impression on the credulous and superstitious mind of

the 'British Solomon,’ and they appear to have led to the composition of

his noted work, the Demonologie.

Numerous other trials for

witchcraft took place during the reign of James. The unhappy victims of

ignorance and credulity were usually charged with removing or laying

diseases on men or cattle, with destroying crops, sinking ships and

drowning mariners, holding meetings with the devil, raising and

dismembering dead bodies for the purpose of obtaining charms, and other

offences of a similar kind. After the death of James the epidemic seems

to have abated somewhat in virulence, for from 1623 to 1640 there are

only eight trials for witchcraft entered on the records of the

Justiciary Court, and, strange to say, in one case the alleged criminal

was acquitted. Counsel for the accused, too, ventured to impeach the

credibility of confessions made by alleged witches on the ground that “

all lawyers agree that they are not really transported, but only in

their fancies while asleep, in which they sometimes dream they see

others” at their orgies. During the Civil War and the Commonwealth,

however, the crime of witchcraft seems to have been greatly on the

increase, although the judges appointed by Cromwell discountenanced

proceedings against reputed witches. Between 1640 and the Restoration no

fewer than thirty trials appear on the records, while an immensely

larger number of accused persons were handed over to commissions,

composed of‘ understanding gentlemen’ and ministers, appointed by the

Privy Council to examine and try those accused of witchcraft in their

respective localities. No fewer than fourteen of these commissions were

appointed in one day in 1661, and many hundreds of persons, principally

aged females, were put to death about this period for the imaginary

crime. The calendar became even more bloody for some time after the

Restoration, when the restrictions imposed by the Republican

justiciaries were removed, and during the year 1661 twenty persons were

condemned for witchcraft. In 1662 occurred the famous case of the

Auldearn Witches, whose confessions are unrivalled in interest. Dr.

Taylor says that one of these beldames, named Isabel Gowdie, who must

have been crazed, gave a most minute and quite unique account of the

proceedings of the ‘covin’ (company) of witches to which she belonged.

She was examined at four different times, between April 13 and May 27,

1662, before a tribunal composed of the sheriff of the county, the

parish minister, seven country gentlemen, and two townsmen $ and though

her conceptions are almost inconceivably absurd and monstrous, her

narrative is quite consistent throughout. She was devoted, she said, to

the service of the devil in the kirk of Auldearn, where she renounced

her Christian baptism and was baptized by the devil in his own name with

blood which he sucked from her shoulder and sprinkled on her head. The

witch covin to which she belonged consisted of the usual number of

thirteen females, one of whom, called the Maiden of the Covin, was

always placed close beside Satan, and was treated with particular

attention, as he had a preference for young women, which greatly

provoked the spite of the old hags. Each of the covin had a nickname, as

‘Pickle,’ ‘Nearest-the-wind,’ ‘Through-the-cornyard,’ ‘Able-and-stout,’

‘Over-the-dike-with-it,’ &c., and each had an attendant spirit,

distinguished by some such name as ‘Red Reiver,’ ‘Roaring Lion,’ ‘Thief

of Hell,’ and so forth. These imps were clothed some in saddum, some in

g rass-green, some in sea-green, some in yellow, some m black. Satan

himself had several spirits to wait on him. He is described as “a very

mickle, black, rough man.” Sometimes he had boots and sometimes shoes on

his feet, but still his feet appeared forked and cloven. A great meeting

of the covin took place quarterly, when a feast was held. The devil took

the head of the table, and all the covin sat around. One of the witches

said grace as follows:

We eat this meat in the

Devil's name,

With sorrows and sichs [sighs] and mickle shame.

We shall destroy house and hald,

Both sheep and nolt intil the fauld.

Little good shall come to the fore

Of all the rest of the little store.

When the meal was ended

the company looked steadfastly at their president and said, “We thank

thee, our Lord, for this.”

The witches, it appears,

sometimes took considerable liberties with their master’s character, and

called him ‘Black John ’ and the like, and he would say, “I ken weel

eneuch what ye are saying of me,” and then he would beat and buffet them

very sore. They were beaten, too, if they were absent from meetings or

neglected any of their master’s injunctions. He found, however, the

wizards much more easily intimidated than his adherents of the other

sex. “Alexander Elder,” says Isabel Gowdie, “was soft and could never

defend himself in the least, but would greet and cry when Satan would be

scourging him. But Margaret Wilson would defend herself fiercely, and

cast up her hands to keep the strokes off her ; and Bessie Wilson would

speak crusty, and be belling again to him stoutly. He would be beating

and scourging us all up and dow n with cords and other sharp scourges,

like naked ghaists and we would still be crying 'Pity, Pity' Mercy,

Mercy; Our Lord.’ But he would have neither pity nor mercy.”

When the married witches

went out to their nocturnal conventions they left behind them in bed a

besom or three-legged stool, which would assume their similitude till

their return and prevent their husbands from missing them. When they

wished to ride, a corn straw between their legs served as a horse, and

on their crying “Horse and hattock, in the devil’s name!” or pronouncing

thrice the following charm:

Horse and hattock, horse

and go,

Horse and pell at, ho, ho, hoI

they were borne through

the air to their destination, even as straws would fly upon a highway.

If any seeing these straws in motion did not sanctify themselves the

witches might shoot them dead. On one such nocturnal excursion the party

feasted in Darnaway Castle, the seat of the Earl of Moray. On another

occasion they went to the Downy Hills} a hill opened, and all went into

a well-lighted room, where they were entertained by the Queen of the

Fairies.

The covin frequently

assumed the shapes of crows, hares, cats, and other animals, by the use

of some such charm as the following:

I shall go intill a hare,

With sorrow, sich, and mickle care.

And I shall go in the Devil's name,

Aye, till I come hame again.

Isabel herself had an

adventure while in the shape of a hare, she said. She was going one

morning about daybreak to Auldearn in that disguise, but had the

misfortune to meet Peter Papley of Killhill’s servant going to work,

having his hounds with him. The dogs immediately gave chase. "I,” says

Isabel, "I ran very long, but was forced, being weary at last, to take

to mine own house. The door being left open, I ran in behind a chest,

and the hounds followed in } but they went to the other side of the

chest and I was forced to run forth again, and ran into another house,

and there took leisure to say :

"Hare, hare, God send thee

care.

I am in a hare’s likeness now,

But I shall be a woman even now.

Hare, hare, God send thee care.'

And so I returned to mine

own shape again.” The dogs, she added, "will sometimes get bits of us,

but will not get us killed. When we return to our own shape, we will

have the bits and rives and scarts on our bodies.”

One common mode of

detecting witches was that of running pins into their bodies, on

pretence of discovering the devil’s mark, which was alleged to be set on

a spot insensible of pain. The persons who acted as 'prickers’ of

witches were allowed to torture those suspected of witchcraft at their

pleasure, as if they were following a lawful and useful occupation. At

length this brutal practice drew down the reprobation of the Privy

Council, and the prickers were punished as common cheats.

Tortures of a much

severer kind were often employed to extort from the reputed witches an

acknowledgment of their guilt. Sometimes they were hung up by the

thumbs, till, nature being exhausted, they were fain to confess whatever

was laid to their charge. At other times they were subjected to cold and

hunger till their lives became a burden. In many cases the thumbikins

and other similar instruments of torture were employed to extort a

confession.

A dreadful execution for

sorcery was that of Lady Jane Douglas, a young and very beautiful woman.

This lady, according to a writer in Miscellanea Scotica, was the most

renowned beauty in Britain at that time. “She was of ordinary stature,

but her mien was majestic, her eyes full, her face oval, her complexion

delicate and extremely fair; heaven designed that her mind should want

none of those perfections possible to a mortal creature; her modesty was

admirable, her courage above what could be expected from her sex, her

judgment solid, and her carriage winning and affable to her inferiors.”

She was accused by a disappointed lover, William Lyon, of sorcery, and

was committed to the prison in David’s Tower along with her second

husband, Archibald Campbell, her little son, Lord Glammis, and an old

priest. The unfortunate lady was first subjected to dreadful torture on

the rack ; then she was led through the Castle gates on to the Hill,

where she was chained to a stake round which had been piled tar-barrels

and faggots, and within full view of her son and husband was burnt to

death. Amongst others who suffered the same fate was Bessie Dunlop, in

1570, who practised as a ‘ wise woman ’ in the cure of some diseases,

for which she ‘was worried’ at the stake. Thirty years after Isabel

Young was treated in the same barbarous fashion for the crime of u

laying sickness on various persons.” In 1608 a wizard was convicted of

healing by sorcery, and suffered like the rest at the stake on Castle

Hill. “He learned frae the Devil, his master, in Binnie Craigs and

Corstorphine, where he met with him and consulted with him divers tymes,

whiles in the likeness of a man, whiles in the likeness of an horse.” He

also, it was alleged, had attempted to destroy the crops of a farmer of

the name of David Liberton by placing a piece of enchanted flesh under

the door of his mill, and had, in addition, been guilty of making an

image in wax and thereafter melting it in the fire, which process was a

method of taking David’s life.

But besides these

revolting memories there are other associations not quite so dreadful

that make the old approach to the fortress interesting. Grant tells us

that on the north side of the Hill there was an ancient church, some

remnant of which was visible in Maitland’s time in 1753. It is supposed

to have been dedicated to St. Andrew, the patron of Scotland, and is

referred to in a deed of gift of twenty merkes yearly, Scottish money,

to the Trinity altar therein, by Alexander Curor, Vicar of Livingstone,

December 20, 1488. In June 1754, when some workmen were levelling this

portion of the Castle Hill, they discovered a subterranean chamber,

fourteen feet square, wherein lay a crowned image of the Virgin, hewn of

very white stone, two brass altar candlesticks, some trinkets, and a few

ancient Scottish and French coins. Remains of burnt matter and two large

cannon-balls were also found there. This edifice was supposed to have

been demolished during one of the sieges suffered by the Castle after

the invention of artillery. In December 1849, when the Castle Hill was

being excavated for a new reservoir, several finely carved stones were

found among what were understood to be the foundations of this chapel or

of Christ Church. The latter building was commenced in 1637, and had

actually proceeded so far that Gordon of Rothiemay shows it in his map

with a high pointed spire. It was abandoned, however, and its materials

used in the erection of the present church at the Tron. This was also

the site of the ancient waterhouse.

On the Castle Hill lay

the great and famous Blew Stone, and it was eventually buried there. A

curious set of doggerel lines appears in Archxologia Scotica on this

landmark, which possibly took the form of a great boulder.

Our old Blew Stone, that's

dead and gone,

His marrow may not be

War: e, twenty feet in length he was,

His bulk none e'er did ken;

Dour and dief and run with grief

When he preserved men.

Behind his back a batterie was,

Contrived with packs of woo.

Wefs now think on, since he is gone,

We're in the Castle's view.

The 'packs of woo’ are

the woolpacks that were used as cover for the troops of William when

besieging the Castle. On the north side of the Esplanade is the quaint

little house (the Goose Pie) of Allan Ramsay, the famous author of the

Gentle Shepherd\ who in 1725 opened a circulating library of fiction for

the benefit of the citizens of Edinburgh. The magistrates looked on this

fiction with some distrust, fearful that it would contaminate the youth

of the city, and made an attempt to prevent Ramsay from pursuing the

business, but without success. It was Allan Ramsay who built one of the

first theatres in Edinburgh, which stood in Carrubber’s Close. A little

higher up, and facing on the Castle Hill, is the fine block built by

Professor Geddes as a students’ settlement. Here also the Professor

himself resides, and his house is the resort of many men of letters and

art in Edinburgh. Close by is the Outlook Tower, containing a fine

collection of old Edinburgh prints, besides a camera obscura.

There are many old houses

on the Hill that bring back memories of the days when the aristocracy of

the city lived in state within the shadow of the Castle’s battlements.

In the wall of one directly facing the Esplanade we find the cannon-ball

which a fanciful but impossible tradition says was fired from the Castle

guns during the blockade of the ‘’45.’ Close by stood the mansion of the

Dukes of Gordon; nothing but the old lintel over the modern doorway

remains, carved with the Gordon arms. The United Free Assembly Hall

stands on the site of the residence of Mary of Guise, and almost next

door lived the famous Dr. Alexander Webster. Hard by stood the house of

the great Duke of Argyll, for many years rented by a tailor at /'12 per

annum. On the north side the famous Laird of Cockpen had his town

residence, and near it was the mansion of the Earl of Leven, who

succeeded the Duke of Gordon as governor of the Castle in 1689. He did

no credit to his family by his behaviour, for, according to the

{Miscellanea Scotica, “if her Majesty Queen Anne had been rightly

informed of his care of the castle, where there were not ten barrels of

gunpowder when the Pretender was on the coast of Scotland, and of his

discourteous behaviour to ladies—particularly how he horsewhipped the

Lady Mortonhall—she would not have made him a general for life.”

The Butter Tron, or

weigh-house, which was held by the Highlanders during the blockade of

the Castle bv Prince Charlie, stood at the bottom of the Hill, near the

Lawnmarket. It was the scene of a quarrel between Major Somerville and a

Captain Crawford, which is related in detail in The Memories of the

Sometvilles. It appears that when Major Somerville commanded the

garrison of the Covenanters in the Castle, Captain Crawford, who was not

in command of any of the troops lying there, demanded admission to the

fortress from the sentry on duty \ whereupon the sentry inquired his

name, that he might take it to his commanding officer before admitting

him. At this the Captain lost his temper and replied, “Your major is

neither a soldier nor a gentleman, and if he were without this gate, and

at a distance from his guards, I would tell him that he was a pitiful

scullion to boot.” Turning on his heel, he tramped down the Castle Hill

in a rage, but was overtaken by the Major, who had by this time received

his message. “ Sir,” said the Major, “ you must permit me to accompany

you a little way, and then you shall know more of my mind.” 'I" Captain

replied, “I will wait on you where you please.” When they reached the

foot of the Hill the Major, drawing his sword, said, "Now I am without

the Castle gates and at a distance from my guards, draw, and make good

your threat.” Crawford evidently thought better of it, and, taking off

his hat, begged his senior officer’s pardon, whereupon Major Somerville,

after thrusting his sword back into its scabbard, remarked, “You have

neither the discretion of a gentleman nor the courage of a soldier.

Begone, for a coward and fool fit only for Bedlam,” and retraced his way

to the Castle. In revenge for the accusation of cowardice, Crawford

later made an attack upon Somerville, and for this he was sentenced to

imprisonment for a year. |