|

A FEW days after receiving

my orders I was informed that the Emperor, while at the opera, had

received intelligence that the Austrians had crossed the Inn on April

12th. It occurred to me as probable, and my idea was eventually

verified, that on the same day they would most likely commence

hostilities and operations in the North of Italy. I therefore started

the day after the Emperor had received the news.

I only halted for a few

hours at Turin to see General Caesar Berthier, who was employed there, I

forget in what capacity. He informed me that hostilities had been

recommenced, and told me of the first success of our troops —five or six

hundred prisoners taken, and two pieces of artillery. He had first

transmitted the news to Paris in a telegraphic despatch, adding that the

whole army was advancing. I was still so far away, that I feared I might

not be able to come up with them before some Important engagement: and,

in spite of the entreaties of the General and his wife that I would stay

and rest at least four-and-twenty hours, I started again immediately.

When I reached Milan, I

found that no one knew anything of the supposed victory that had been

telegraphed from Turin to Paris; even the whereabouts of the army was

unknown. I was a stranger in the town, though I had spent a few weeks

there in 1798, just before I was sent to take the command in Rome; I had

then known a few French officers, but they were all absent now.

However, a certain Signor

Bignami, a banker, having accidentally heard of my arrival, came to see

me, and told me confidentially that he knew, from commercial sources,

that the army had met with a check. and was retreating, though few

people had as yet been informed. I tried to prove to him that he was

mistaken by quoting what General Berthier had said; but he shook his

head, and his assurance began to make me think that there really was

something in his commercial intelligence.

It was too late for me to

present my respects to the Vice-Queen; but among other names that he

mentioned to me as belonging to persons attached to her Court, he spoke

of Comte Méjean, whom I knew a little, and offered to take me to the

palazzo where he dwelt.

We learned that Monsieur

Mjean was at the Council. I gave my name to the usher, desiring him to

inform that personage that, as I was only passing through Milan on my

way to the army, I should be much obliged if he could tell me where the

headquarters were, and whether the Vice-Queen had any messages for her

husband. On hearing my name, he quitted the Council, and hastened to me;

he took me aside, and confided to me that a courier, the previous night,

had brought intelligence even more disastrous than that of which Bignami

had spoken. The letter brought by the courier was couched in more or

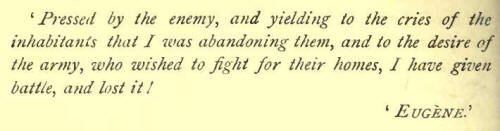

less the following terms

'['hereupon I said that I

must at once have horses and start. He urged me to come and see the

Vice-Queen, and offered to accompany me, assuring me that she would

forego etiquette. But, as I was in travelling dress, I begged him to

tell the Princess that I thought the best means of showing my devotion,

and of being agreeable to her, would be to go direct to her husband's

headquarters. Before leaving Mjean, he begged me to say nothing to

Bignami, who would be sure to cross-question me. I limited my replies to

saying that at Court they could add nothing to the news he had already

received, and that no belief was placed in it. We separated, and I got

into my carriage very downcast at this rebuff.

A battle in Italy,

however serious it might be, could only be of secondary importance. The

decisive point was Germany, where the Emperor was commanding in person.

But it might have a bad effect upon the Italian mind, already prejudiced

against us, kept under as they were, but not conquered; and upon that of

the Germans and their armies, although they had been so often beaten,

and their territory so often invaded by us. But they were like the teeth

of Cadmus no sooner was one army destroyed than another carne to take

its place. They seemed to rise out of the ground.

I had a high opinion of

the military talents of the Emperor, who had so often performed

miracles; I trusted him now, and I was right.

Between Brescia and

Verona, at a place called Desenzano, on the Lake of Garda, I met a

Colonel whose name I have forgotten. Still terrified at what he had

witnessed and heard, and believing that the enemy were at his heels, he

had just left headquarters, but was unable to tell me where they were

situated. He was carrying orders to arm and provision all the forts in

Piedmont—in short, to put them into a proper condition of defence. The

disaster must have been considerable to necessitate such hasty orders

This Colonel was in such

a hurry, that I could obtain no details from him. Some leagues farther

on I found the terror increasing, and it became worse as I drew nearer

to the scene. I met a courier on his way from headquarters to the

Emperor; not even he could tell me whence he had started, and all that I

could extract from him was that he had been sent after this unfortunate

battle.

At length I reached

Verona. All was in confusion. The wounded were coming in large numbers,

as well as fugitives, riderless horses, carts, baggage-waggons,

carriages, crossing each other, meeting, blocking the streets, and

filling the squares; in short, all the horrors of a rout. The siege

artillery stationed on the glacis had been promptly removed to Mantua.

The authorities were without news; and crowded round me to ask for some.

I could scarcely believe that I had come there in order to obtain

information myself. Rumour said that the army was marching for Mantua,

where it would rally: but it seemed to me impossible that, however great

might have been the misfortune, they should abandon the high road to the

Milanese capital.

Notwithstanding all the

warnings I received upon the dangers I should meet along this road, I

resolved to follow it, and was glad I had done so. Scarcely had I left

the gates early next morning, when a courier appeared. He came from

Vicenza, where he had left the Viceroy, who was just preparing to start

for Verona. This courier was carrying orders to the siege-train to make

for Mantua, an order which, as I have said, had been forestalled. I did

not stop to interrogate this letter-carrier, as I was now within a few

hours of headquarters.

I entered Vicenza, to the

surprise of all who saw a carriage coming in the opposite direction to

that followed by all the others, which would, moreover, have soon been

followed by troops, had it not been for my unexpected appearance. News

of my arrival soon spread, and the inn where I stopped was blocked with

visitors and inquirers. The army was to a great extent formed of troops

that I had had under my orders when I commanded in the Roman States and

in Naples, so that I felt quite at home. Everyone gave me a different

version of what had occurred, and, as usual, laid the blame upon the

inexperience of their leader, the jealousy of the Generals, and so on.

The Viceroy, who from his

windows had seen a post-chaise pass, suspected that I might have come,

and sent several aides-de-camp to find out and to desire me to come

straight to him. He received me cordially, or, I might say, effusively.

He was even more taken up with what the Emperor would say and write than

with the affair itself.

'I have been beaten,' he

said, 'at my first attempt in commanding, and in a bad place too. The

Emperor will be furious; he knows his Italy so well'.

'What induced you to

fight?' I asked. One can generally refuse a battle. And in such a

position too, with that narrow gorge behind you, which made retreat so

difficult in case of necessity! You are very lucky not to have had to do

with a bold, enterprising enemy, otherwise every hope of safety for your

army must have been abandoned.'

'That is true,' he

answered. 'I yielded too easily to the prayers and complaints of the

Emperor's subjects. I was surrounded, deafened by their cries that I was

abandoning them without striking a blow. The army grumbled at having to

retreat before a foe that they had so often vanquished before. I

consulted and asked the advice and opinion of all the most experienced

Generals.'

It seems that all the

latter had been satisfied with a laconic answer, to the effect that he

was the chief, that he had only to give his orders, and they should be

carried out; that the responsibility was too great for them. Which,

being interpreted, meant, 'Get out of the difficulty as best you can.'

These answers having roused his wrath, he only consulted his pluck, and

without reflecting on possible consequences, gave battle and lost it.

'Never in future,' I

said, 'give way to annoyance, or act precipitately. You see into what

straits it has brought you. Where are you going now, and what do you

mean to do?'

'Everyone is

disheartened; no one speaks of anything but retreat. The orders are

given and are being carried out at this moment.'

'Where is the enemy?'

'About three marches from

here.'

'Three marches, indeed.

What would you do if they were on your heels? Is not this the home of

trickery? Let me look at your maps and see if there is not some way out

of the hole. If I remember rightly, a little river runs across here

somewhere, with a canal and a number of brooks, which might easily he

defended; dispute the Alpone on your rear, then Caldiero, through which

I have just passed, but which would be a better position for the enemy,

then the Adige, etc. Remember that the great issue will be fought out in

Germany. You will learn the results, not from messengers, but from the

movements of your adversary; if they are rapid, it will mean that they

have been victorious; if they are slow, as at this moment, it will mean

that nothing is settled yet; if they are beaten, your adversary will

retire, because he will not wish to abandon his communications with the

capital, nor to be flanked and cut off by the victorious army that had

just defeated him.'

To these reasons I added

many others, not less powerful and convincing:

'If you retire without

fighting from a position so easy to defend, the enemy will follow you.

Where will you stop? On the rivers, or on the Alps? Now, if the Emperor

is successful, and sends you orders to take the offensive again, you

will have to try and force your way across these rivers. Shall you

succeed with a discouraged army? It is doubtful. Do not let us therefore

expose ourselves to such an accident, if we can avoid it; let us defend

our ground foot by foot, and compromise nothing; finally, let us not

risk a second battle, and do nothing unless we are sure.'

My arguments made an

impression upon the mind of this really courageous and high-spirited

young man. I continued:

'Summon the Generals in

whom you have most confidence, tell them your intentions, and hear what

they have to say.'

'I know that already,' he

answered. 'Look here; there goes one of them with his division. He took

no part whatever in the action, and is now one of the first to be off,

besides giving the worst advice.'

He thereupon gave orders

for the unharnessing of his own carriages, which were preparing to

start, and I returned to my lodgings to wait for the hour agreed upon

for the meeting.

My arrival had produced a

favourable impression in the army. I say it without vanity, ostentation,

or pride. I was liked by my men, and they had confidence in me; I had

always taken a friendly interest in them. It was well known that my

disgrace was the result of prejudice and injustice, and they thought

better of me for agreeing to serve in a capacity inferior to those I had

previously occupied. Hope began to revive even amid these sad

circumstances.

At the meeting there was

present a large number of Generals and superior officers. The Viceroy

explained the position of the army and the suggestions that I had made

to him, and then desired me to lay before the meeting the extension that

might be given to them, which I did very carefully, for fear of hurting

the feelings of my audience. I was heard without interruption, but at

the conclusion of my remarks General Grenier said, addressing himself to

the Viceroy:

'Prince, no word has been

said about the morale of the army, or about its present disorganized

condition; I declare that it is such that I will not answer for my own

division until it has had some days' rest behind the Adige at Verona.'

The others spoke on the

same lines, and the Prince, promising to consider what had been put

before him, broke up the meeting.

When we were alone, he

asked me what I thought of General Grenier. I had had nothing to do with

him, but we had met in the Army of the Sambre and Meuse, when I was

leading thither from Holland fifteen or twenty thousand men from the

Army of the North, just after his defeat in Germany and his retreat upon

the Lahn and the Sieg. He had a good reputation as a

General-of-Division.

'As for morale,' I added,

laughing, 'that of the gentlemen who have just left us seems to me no

less shaken than that of their men. But you have some who took no part

in the action; keep them here and let the others go. They will suffice

for the time being, and you can recall the others in a few days.'

He fell in with my

suggestion. As a matter of fact, we only needed a small number to guard

the passes, and if the worst came to the worst, we were not far from the

Alpone, a torrent between high banks, which would serve us in lieu of

entrenchments. A portion of the troops, therefore, especially those

belonging to General Grenier, were allowed to retire to Verona. General

Pully's cavalry, which either had not been called up, or else had

arrived too late to take part at Sacilio, received orders to reoccupy

Padua, already evacuated in the general retreat that had been ordered

when I arrived, and to which I had put an abrupt conclusion.

We had to consider the

best provisional means of defence for ourselves in this land of

surprises, and rode out to inspect them. The Viceroy was good enough to

make me a present of two horses, as I was without my equipment, which

did not rejoin me, I think, until the month of August. I had, however,

procured what was necessary for the time being.

The bridge of Vicenza

could be easily defended by means of slight works; I suggested to the

Viceroy what might be done, and asked him to order the Major of

Engineers stationed there to carry them out. He called him and explained

to him briefly what was wanted. I noticed that this officer did not

understand a word of what was said to him, although he replied that he

would carry out the instructions. I could not fail to observe it, simply

from noticing the face of the officer in command of this important post,

and I communicated my idea to the Prince, who thought I was joking.

'Call him back then, your

Highness,' said I, 'and ask him to repeat the orders you have just given

him.'

The unlucky Major

stammered and shamefacedly admitted that he had not understood.

'Why did you not ask me

to repeat my orders to you?' inquired the Prince.

'I was wrong,' he

replied, 'and I beg your Highness's pardon.'

A fresh explanation was

given, and we rode away.

'See,' I said to the

Prince, 'how easily mistakes occur. You would have gone away in peace,

thinking that your necessary orders would be carried out. You did not

observe that that officer, no doubt a very brave, good fellow, was not

very bright; for if Heaven had endowed him with ever so small a share of

wits, he would, on his own responsibility, have caused some temporary

defences to be made at a point on which depended so much of the safety

of his own men and of the army. Misunderstandings and blunders are often

fatal, particularly in military matters ; therefore, when I give a

verbal order, I always have it repeated over to me, and have found it a

good plan.'

I advised him to adopt

it, which he did in the future with good results. |