|

THE length of time that has

passed since we made this pleasant little tour in the Netherlands has

caused forgetfulness of a thousand details which always add so much to

the interest of any account of the first impressions of a foreign

country. In talking over our travels with our good friend Miss Bessy

Clerk, we used to keep her laughing by the hour at several of our

adventures. This winter in Edinburgh was our last, passed much as other

winters; the same law dinners before Christmas, the same balls after it.

My mother was very kind to me and did not press me to go out. Jane, who

delighted in company, and who was the most popular young lady in our

society, was quite pleased to have most of the visiting. I was a good

deal with Miss Clerk and the Jeffreys and the Brewsters, at whose house

one day at a quiet dinner I met Sir John Hay and his daughter Elizabeth,

looking so very pretty in the mourning she wore for her betrothed. He

had died of quinsy while on circuit at Aberdeen the year before. She

afterwards married Sir David Hunter Blair.

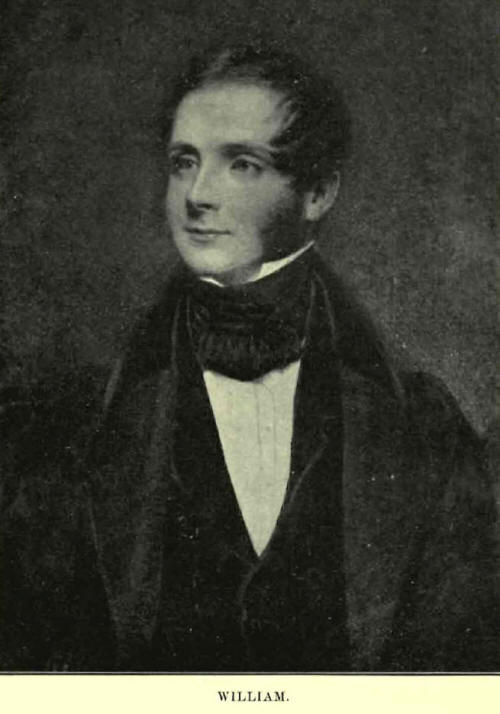

There were serious riots

in the West country this spring of 1820, the yeomanry called out, troops

sent to Glasgow—a serious affair while it lasted. Jane was out at

dinner, my mother was reading to me, when with a grand fuss in came

William Gibson to tell us the strife was over, and to show himself in

all the bravery of his yeomanry uniform; very handsome it was. He and I

had fallen out before we went abroad, and we never rightly fell in

again. He was a little spoiled, known to be the heir of his wealthy

father and still wealthier cousin, Mr Craig of Riccarton; the idea,

therefore, of his studying for the Bar struck us all as absurd. Of

course he did not spend much time on his law books, and his father

determined to send him to travel. My father and mother were sorry to see

him go; he was a favourite, and has turned out so as fully to justify

their partiality.

There were many public

rejoicings although private affairs had been gathering gloom. The old

Queen Charlotte had died and George III.ditto. The Princess Charlotte

had married and had died with her baby, and this had set all her royal

uncles upon marrying to provide heirs to the throne. One after the other

German princesses came over, and in this year began the births, to the

supposed delight of a grateful country We had long tiresome mournings

and then the joy-bells —the old tale. But there were other losses more

felt. Madame de Staël died, to the regret of Europe. We had heard so

much of her through the Mackintoshes that we almost fancied her an

acquaintance. I think the Duke of York must have died too, and Mrs

Canning —but maybe this was later. I am confused about dates, having

never made any memoranda to guide me. Altogether my recollections of

these few last months in Edinburgh are rather confused and far from

pleasant.

One morning my mother

sent Jane and Mary with a message to the poor Carrs in the Abbey;

William was out elsewhere; most of the servants were despatched on

errands; and then, poor woman, she told me there was to be an execution

in the house, and that I must help her to ticket a few books and

drawings as belonging to the friends who had lent them to us. We had

hardly finished when two startling rings announced the arrival of a

string of rude-looking men, who proceeded at once to business, however,

with perfect civility, although their visit could not have been

satisfactory, inasmuch as nothing almost was personal property; the

furniture was all hired, there was no cellar, very little plate. The law

library and the pianoforte were the most valuable items of the short

catalogue. I attended them with the keys, and certainly they were very

courteous, not going up to the bedrooms at all, nor scrutinising

anywhere very closely. When they were gone we had a good fit of crying,

my mother and I, and then she told me for the first time of our

difficulties as far as she herself knew them, adding that her whole wish

now was to retire to the Highlands; for, disappointed as she had been in

every way, she had no wish to remain before the public eye nor to

continue an expensive way of living evidently beyond our circumstances.

How severely I reflected on myself for having added to her griefs, for I

had considerably distressed her by my heartless flirtations, entered on

purposely to inflict disappointment. The guilt of such conduct now came

upon me as a blow, meriting just as cruel a punishment as my awakening

conscience was giving me; for there was no help, no cure for the past,

all remaining was a better line of conduct for the future, on which I

fully determined, and, thank God, lived to carry out, and so in some

small degree atone for that vile flippancy which had hurt my own

character and my own reputation while it tortured my poor mother. I

don't now take all the blame upon myself; I had never been rightly

guided. The relations between mother and daughter were very different

then from what they are now. Our mother was very reserved with us, not

watchful of us, nor considerate, nor consistent. The governess was an

affliction. Thought would have schooled me; but I never thought till

this sad day; then it seemed as if a veil fell from between my giddy

spirits and real life, and the lesson I read began my education. Mary

had also grieved my poor mother a little by refusing uncle Edward's

invitation to India; Jane, by declining what were called good marriages;

William, by neglecting his law studies. A little more openness with

kindness might have done good to all ; tart speeches and undue

fault-finding will put nothing straight, ever. We had all suffered from

the fretfulness without knowing what had caused the ill-humour. It was

easy to bear and easy to soothe once it was understood. We were all the

happier after we knew more of the truth of our position.

It was easy to get leave

to spend the summer in Rothiemurchus; it was impossible to persuade my

father that he had lost his chance of succeeding at the Scotch Bar. He

took another house in Great King Street, removing all the furniture and

his law books into it, as our lease of No. 8 Picardy Place was out. My

mother, who had charge of the packing, put up and carried north every

atom that was our own. She had made up her mind to return no more,

though she said nothing after the new house was taken. Had she been as

resolute earlier it would have been better; perhaps she did not know the

necessity of the case; and then she and we looked on the forest as

inexhaustible, a growth of wealth that would last for ever and retrieve

any passing difficulties, with proper management. This was our sunny

gleam.

In July then, 1820, we

returned to the Highlands, which for seven years remained the only home

of the family. My mother resisted all arguments for a return to

Edinburgh this first winter, and they were never again employed. She had

begun to lose her brave heart, to find out how much more serious than

she had ever dreamed of had become the difficulties in which my father

was involved, though the full amount of his debts was concealed for some

time longer from her and the world. Some sort of trust-deed was executed

this summer, to which I know our cousin lame James Grant, Glenmoriston's

uncle, was a party. William was to give up the Bar, and devote himself

to the management of the property, take the forest affairs into his own

hands, Duncan Macintosh being quite invalided, and turn farmer as well,

having qualified himself by a residence of some months in East Lothian

at a first-rate practical farmer's, for the care of the comparatively

few acres round the Doune. My father was to proceed as usual; London and

the House in spring, and such improvements as amused him when at home.

My mother did not enjoy a

country life; she had therefore the more merit in suiting herself to it.

She had no pleasure in gardening or in wandering through that beautiful

scenery, neither had she any turn for schools, nor "cottage comforts,"

nor the general care of her husband's people, though in particular

instances she was very kind; nor was she an active housekeeper. She

ordered very good dinners, but as general overseer of expenditure she

failed. She liked seeing her hanks of yarn come in and her webs come

home; but whether she got back all she ought from what she sent, she

never thought of She had no extravagant habits, not one; yet for want of

supervision the waste in all departments of the household was excessive.

Indolently content with her book, her newspaper, or her work, late up

and very late to bed, a walk to her poultry-yard, which was her only

diversion, was almost a bore to her, and a drive with my father in her

pretty pony carriage quite a sacrifice. Her health was beginning to give

way and her spirits with it.

William was quite pleased

with the change in his destiny. He was very active in his habits, by no

means studious, and he had never much fancied the law. Farming he took

to eagerly, and what a farmer he made. They were changed times to the

Highland idlers: the whole yard astir at five o'clock in the morning,

himself perhaps the first to pull the bell, a certain task allotted to

every one, hours fixed for this work, days set apart for that, method

pursued, order enforced. It was hard, uphill work, but even to tidiness

and cleanliness it was accomplished in time. He overturned the old

system a little too quickly, a woman would have gone about the requisite

changes with more delicacy; the result, however, justified the means.

There was one stumbling- block in his way, a clever rogue of a grieve, a

handsome well-mannered man, a great favourite, who blinded even William

by his adroit flatteries. He came from Ayrshire, highly recommended by I

forget whom, and having married Donald Maclean the carpenter's pretty

daughter, called Jane after my mother, he had a strong back of

connections all disposed to be favourable to him. He was gardener as

well as grieve, for George Ross was dead, and he was really skilful in

both capacities.

The forest affairs were

at least equally improved by such active superintendence, although the

alterations came more by degrees. I must try and remember all that was

done there, and in due order if possible. First, the general felling of

timber at whatever spot the men so employed found it most convenient to

them to put an axe to a marked tree, was put a stop to. William made a

plan of the forest, divided it into sections, and as far as was

practicable allotted one portion to be cleared immediately, enclosed by

a stout fencing, and then left to nature, not to be touched again for

fifty or sixty years. The ground was so rich in seed that no other

course was necessary. By the following spring a carpet of inch-high

plants would be struggling to rise above the heather, in a season or two

more a thicket of young firs would be.found there, thinning themselves

as they grew, the larger destroying all the weaker. Had this plan been

pursued from the beginning there would never have been an end to the

wood of Rothiemurchus. The dragging of the felled timber was next

systematised. The horses required were kept at the Doune, sent out

regularly to their work during the time of year they were wanted, and

when their business was done employed in carting deals to Forres,

returning with meal sufficient for the consumption of the whole place,

or to Inverness to bring back coals and other stores for the house. The

little bodies and idle boys with ponies were got rid of. The mills also

disappeared. One by one these picturesque objects fell into disuse. A

large building was erected on the Druie near its junction with the Spey,

where all the sawing was effected. A coarse upright saw for slabbing,

that is, sawing off the outsides or backs of the logs, and several packs

of saws which cut the whole log up at once into deals, were all arranged

in the larger division of the mill. A wide reservoir of water held all

the wood floated or dragged to the inclined plane up which the logs were

rolled as wanted. When cut up, the backs were thrown out through one

window, the deals through another, into a yard at the back of the mill,

where the wood was all sorted and stacked. Very few men and as many boys

got easily through the work of the day. It was always a busy scene and a

very exciting one, the great lion of the place, strangers delighting in

a visit to it. The noise was frightful, but there was no confusion, no

bustle, no hurry. Every one employed had his own particular task, and

plenty of time and space to do it in.

The smaller compartment

of the great mill was fitted up with circular saws for the purpose of

preparing the thinnings of the birch woods for herring-barrel staves, it

was a mere toy beside its gigantic neighbour, but a very pretty and a

very profitable one, above £i000 a year being cleared by this

manufacture of what had hitherto been valueless except as fuel. This

circular saw-mill had been the first erected. It was planned by my

father and William the summer they went north with my mother and left us

girls in Edinburgh. The large mill followed, and was but just finished

as we arrived, so that it was not in the working order I have described

till some months later. An oddity, Urquhart Gale, imported a few years

before, had entire charge of it, and Sandy Macintosh gave all his

attention to the woods. He lived with his father at the Dell, and

Urquhart Gale lived on one of the islands in the Druie, where he had

built himself a wooden house surrounded by a strip of garden bounded by

the water. Having set the staple business of the place in more regular

order than it had ever been conducted in before, William turned his

attention to the farm, with less success, however, for a year or two.

More work was done and all work was better done, but the management

remained expensive till we got rid of the grieve. In time he was

replaced by a head ploughman from the Lothians, when all the others

having learnt their places required less supervision. William indeed was

himself always at his post, this new profession of his being his

passion. The order he got that farm into, the crops it yielded

afterwards, the beauty of his fields, the improvement of the stock, were

the wonder of the country. This first year I did not so much attend to

his doings as I did the next, having little or nothing to do with his

operations. Jane and I rode as usual. We all wandered about in the woods

and spent long days in the garden, and then we had the usual autumn

company to entertain at home and in the neighbourhood.

Our first guest was John,

our young brother John, whom we had not seen since he went first to

Eton. My mother, whose anxiety to meet her pet was fully equal to my

sisters' and mine, proposed our driving to Pitmain, thirteen miles off,

where the coach then stopped to dine. The barouche and four was ordered

accordingly and away we went. We had nearly reached Kingussie when we

espied upon the road a tall figure walking with long strides, his hat on

the back of his head, his hair blowing about in the wind, very short

trousers, and arms beyond his coat-sleeves—in fact an object: and this

was John! grown five inches, or indeed I believe six—for he had been

sixteen months away. He had carried up very creditable breadth with all

this height, looking strong enough, but so altered, so unlike our little

plaything of a brother, we were rather discomfited. However, we found

that the ways of old had lost no charms for the Eton boy; he was more

our companion than ever, promoting and enjoying fun in his quiet way,

and so long as no sort of trouble fell to him, objecting to none of our

many schemes of amusement. Old as we elder ones were, we used to join in

cat concerts after breakfast; my mother always breakfasted in her room,

my father had a tray sent to him in the study, or if he came to us, he

ate hurriedly and soon departed. We each pretended we were playing on

some instrument, the sound of which we endeavoured to imitate with the

voice, taking parts as in a real orchestra, generally contriving to make

harmony, and going through all our favourite overtures as well as

innumerable melodies. Then we would act scenes from different plays,

substituting our own words when memory failed us, or sing bits of operas

in the same improvisatore style. Then we would rush out of doors, be off

to fish, or to visit our thousand friends, or to the forest or to the

mill, or to take a row upon the loch, unmooring the boat ourselves, and

Jane and I handling the oars just as well as our brothers. Sometimes we

stopped short in the garden or went no further than the hill of the

Doune, or maybe would lounge on to the farmyard if any work we liked was

going on there. Jane had taken to sketching from nature and to

gardening. I had my greenhouse plants indoors, and the linen-press, made

over to my care by my mother, as were the wardrobes of my brothers. We

were so happy, so busy, we felt it an interruption when there came

visitors, Jane excepted; she was only in her element when in company.

She very soon took the whole charge of receiving and entertaining the

guests. She shone in that capacity and certainly made the gay meetings

of friends henceforward very different from the formal parties of former

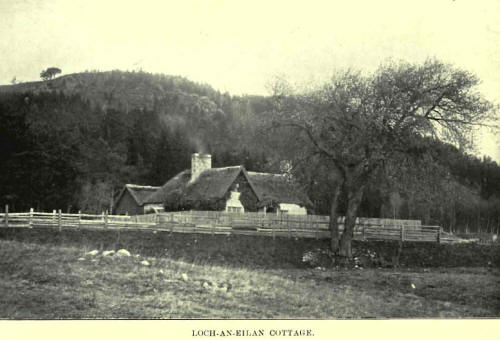

times. Our guests this autumn of 1820 were Charles and Robert Grant

(names ever dear to me), Sir David and Lady Brewster, and Mrs Marcet the

clever authoress, brought to us by the Bellevilles. We gave her a

luncheon in our cottage at Loch-an-Eilan, which much pleased her. Our

cousin Edmund was with us this summer; he had helped us to fit up the

cottage, whitewashing, staining, painting, etc. One of the woodmen's

wives lived in it and kept it tidy. We had a pantry and a store-room,

well furnished both of them, and many a party we gave there, sometimes a

boating and fishing party with a luncheon, sometimes a tea with cakes of

our own making, and a merry walk home by moonlight. Doctor Hooker also

came to botanise and the sportsmen to shoot. Kinrara filled, and uncle

Ralph and Eliza passed the whole summer with us. Mrs Ironside was at

Oxford, watching with aunt Mary the last days of Dr Griffith. Uncle

Ralph was the most delightful companion that ever dwelt in a country

house. Never in the way, always up to everything, the promoter of all

enjoyment, full of fun, full of anecdote, charming by the fire on a wet

day, charming out of doors in the sunshine, enthusiastic about scenery,

unrivalled in weaving garlands of natural flowers for the hair,

altogether such a prose poet as one almost never meets with; hardly

handsome, yet very fine-looking, tall and with the manners and the air

of a prince of the blood. He had lived much in the best society and had

adorned it. Eliza was clever, very obliging, and her playing on the

pianoforte was delightful. She had an everlasting collection of old

simple airs belonging to all countries, which she strung together with

skill, and played with expression. We had great fun this autumn; pony

races at Kingussie and a ball at the cattle tryst, picnics in the woods,

quantities of fine people at Kinrara, Lord Tweeddale and his beautiful

Marchioness (Lady Susan Montague), the Ladies Cornwallis, kind merry

girls, one of them—Lady Louisa —nearly killing uncle Ralph by making him

dance twice down the haymakers with her; Mrs Rawdon and her clever

daughter, Lady William Russell; Lord Lynedoch at eighty shooting with

the young men; Colonel Ponsonby, who had gambled away a fine fortune or

two and Lady Harriet Bathurst's heart, and being supposed to be killed

at Waterloo, had his body while in a swoon built up in a wall of

corpses, as a breastwork for some regiment to shoot over. Mrs Rawdon,

rather a handsome flirting widow, taking uncle Ralph for a widower, paid

him tender attentions and invited Eliza to visit her in London.

This was the summer of

Queen Caroline's trial; the newspapers were forbidden to all of us young

people; a useless prohibition, for while we sat working or drawing, my

uncle and my mother favoured us with full comments on these disgusting

proceedings. In September the poor creature died. None of the grandees

in our neighbourhood would wear mourning for her. We had to put on black

for our uncle Griffith, and the good-natured world said that my father,

in his violent Whiggery, had dressed us in sables, when, in truth, he

had always supported the king's right to exercise his own authority in

his own family. Mrs Ralph remained at Oxford to assist aunt Mary in

selecting furniture, packing up some, selling the rest, and giving up

the lodgings to the new master, Dr Rowley, our old friend of the

pear-tree days. The two ladies then set out for Tennochside, where aunt

Mary was to pass her years of widowhood, uncle Ralph and Eliza hurrying

back to meet them as soon as we had returned from the Northern Meeting

in October.

At the end of this year

my sisters and I had to manage amongst us to replace wasteful servants

and attend to my mother's simple wants. The housekeeper went, in bad

health, to the Spa at Strathpeffer, where she died; the fine cook

married the butler, and took the Inn at Dalwhinnie, which they partly

furnished out of our lumber room! My mother placed me in authority, and

by patience, regularity, tact and resolution, the necessary reforms were

silently made without annoying any one. It was the beginning of troubles

the full extent of which I had indeed little idea of then, nor had I

thought much of what I did know till one bright day, on one of our

forest excursions, my rough pony was led through the moss of

Achnahatanich by honest old John Bain. We were looking over a wide, bare

plain, which the last time I had seen it had been all wood; I believe I

started; the good old man shook his grey head, and then, with more

respect than usual in his manner, he told all that was said, all that he

feared, all that some one of us should know, and that he saw "it was

fixed that Miss Lizzy should hear, for though she was light- some she

would come to sense when it was wanted to keep her mamma easy, try to

help her brothers, and not refuse a good match for herself." Poor, good,

wise John Bain! A match for me! that was over, but the rest could be

tried. "A stout heart to a stiff brae" gets up the hill.

I was ignorant of

household matters; my kind friend the Lady Belleville was an admirable

economist, she taught me much. Dairy and farm-kitchen matters were

picked up at the Dell and the Croft, and with books of reference, honest

intentions, and untiring activity, less mistakes were made in this

season of apprenticeship than could have been expected. And so passed

the year of 1821. Few visitors that season, no Northern Meeting, a

dinner or two at Kinrara, and a good many visits at Belleville. William

busy with the forest and farm.

1822 was more lively;

William and I had got our departments into fair working order; whether

he had diminished expenses, I know not; I had, beyond my slightest idea,

and we were fully more comfortable than we had ever been under the reign

of the housekeepers. Sir David and Lady Brewster were with us for a

while, and Dr Hooker, and the Grants of course, with their quaint fun

and their oddities and their extra piety, which, I think, was wearing

away. In the early part of the year aunt Mary came to us from

Tennochside, escorted by my father on his return from London. She found

me very ill. I had gone at Christmas on a visit to our cousins the Roses

of Holme, where I had not been since Charlotte's marriage to Sir John,

then Colonel Burgoyne. There had been no company in the house for some

time; I was put into a damp bed, which gave me a cold, followed by such

a cough that I had kept my room ever since; the dull barrack-room, very

low in the roof, just under the slates, cold in winter, a furnace in

summer, only one window in it, and we three girls in it, my poor sisters

disturbed all night by my incessant cough. Dr Smith, kind little man,

took what care he could of me, and Jane, who succeeded to my

"situation," was the best, the most untiring of nurses, but neither of

them could manage my removal to a more fitting apartment. Aunt Mary

effected it at once. We were all brought down to the white room and its

dressing-room, the best in the house, so light, so very cheerful; I had

the large room. The dear Miss Cumming Gordons sent up from Forres House

a cuddy, whose milk, brought up to me warm every morning, soon soften"'

the cough. Nourishing soups restored strength. In June I was on my pony;

in August I was well. How much I owe to our dear, wise aunt Mary! she

never let us return to the barrack-room; she prevailed on my father to

have us settled in the old schoolroom and the room through it, which we

inhabited ever after; had we been there before I should not have been so

ill, for my mother lived on the same floor, and would have been able to

look after us. She was very ill herself, in the doctor's hands, rose

late, never got up the garret stairs, and was no great believer in the

dangers of a mere cold.

Aunt Mary amused us by her admiration of handsome young men. One of the

Macphersons of Ralea, and the two Clarkes of Dalnavert, John and

William, were very much with us; they were dangerous inmates, but they

did us no harm; I do not know that they did themselves much good. It is

curious how these Highland laddies, once introduced to the upper world,

take their places in it as if born to fill them. No young men school or

college bred could have more graceful manners than John Clarke; he

entered the army from his humble home at Dalnavert, just taught a little

by the kindness of Belleville. He was a first-rate officer, became A.D.C.,

married a baronet's daughter, and suited well the high position he won.

The brother William, a gentlemanly sailor, married a woman of family and

fortune, and settled in Hampshire. The sisters, after the death of their

parents, went to an aunt in South America, where most of them married

well, the eldest to a nephew of the celebrated General Greene. All of

them rose as no other race ever rises; there is no vulgarity for them to

lose. Then came John Dalzel, a good young man, said to be clever, known

to be industrious, educated with all the care that clever parents,

school, college, a good society in Lord Eldin's house, could command;

who, grave, dull, awkward, looked of inferior species to the "gentle

Celts."

This autumn King George

the Fourth visited Scotland. The whole country went mad. Everybody

strained every point to get to Edinburgh to receive him. Sir Walter

Scott and the Town Council were overwhelming themselves with the

preparations. My mother did not feel well enough for the bustle, neither

was I at all fit for it, so we stayed at home with aunt Mary. My father,

my sisters, and William, with lace, feathers, pearls, the old landau,

the old horses, and the old liveries, all went to add to the show, which

they said was delightful. The Countess of Lauderdale presented my two

sisters and the two Miss Grants of Congalton, a group allowed to be the

prettiest there. The Clan Grant had quite a triumph, no equipage was as

handsome as that of Colonel Francis Grant, our acting chief, in their

red and green and gold. There were processions, a review, a levee, a

drawing-room, and a ball, at which last Jane was one of the ladies

selected to dance in the reel before the King, with, I think, poor

Captain Murray of Abercairney, a young naval officer, for her partner. A

great mistake was made by the stage managers—one that offended all the

southron Scots; the King wore at the levee the Highland dress. I daresay

he thought the country all Highland, expected no fertile plains, did not

know the difference between the Saxon and the Celt. However, all else

went off well, this little slur on the Saxon was overlooked, and it gave

occasion for a laugh at one of Lady Saltoun's witty speeches. Some one

objecting to this dress, particularly on so large a man, "Nay," said

she, "we should take it very kind of him; since his stay will be so

short, the more we see of him the better." Sir William Curtis was kilted

too, and standing near the King, many persons mistook them, amongst

others John Hamilton Dundas, who kneeled to kiss the fat Alderman's

hand, when, finding out his mistake, he called, "Wrong, by Jove!" and

rising, moved on undaunted to the larger presence. One incident

connected with this time made me very cross. Lord Conyngham, the

Chamberlain, was looking every- where for pure Glenlivet whisky; the

King drank nothing else. It was not to be had out of the Highlands. My

father sent word to me—I was the cellarer—to empty my pet bin, where was

whisky long in wood, long in uncorked bottles, mild as milk, and the

true contraband gei2i in it. Much as I grudged this treasure it made our

fortunes afterwards, showing on what trifles great events depend. The

whisky, and fifty brace of ptarmigan all shot by one man, went up to

Holyrood House, and were graciously received and made much of, and a

reminder of this attention at a proper moment by the gentlemanly

Chamberlain ensured to my father the Indian judgeship.

While part of the family

were thus loyally employed, passing a gay ten days in Edinburgh, my

dear, kind aunt and I were strolling through the beautiful scenery of

Rothiemurchus. She loved to revisit all the places she had so admired in

her youth. When attended by the train of retainers which then

accompanied her progress, she had learnt more of the ancient doings of

our race than I had been able to pick up even from dear old Mr Cameron.

Aunt Mary was all Highland, an enthusiast in her admiration of all that

fed the romance of her nature, so different from the placid comfort of

her early home. Our strolls were charming; she on foot, I on my pony. We

went long distances, for we often stopped to rest beside some sparkling

burnie, and seated on the heather and beside the cranberries, we ate the

luncheon we had brought with us in a basket that was hung on the crutch

of my saddle. I was much more fitted to understand her fine mind at this

time than I should have been the year before. My long illness, which had

confined me for many months to my room, where much of the time was

passed in solitude, had thrown me for amusement on the treasures of my

father's library. First I took to light reading, but finding there

allusions to subjects of which I was nearly ignorant, I chalked out for

myself a plan of really earnest study. The history of my own country,

and all connected with it, in eras, consulting the references where we

had them, studying the literature of each period, comparing the past

with the present—it was this course faithfully pursued till it

interested me beyond idea, that made me acquainted with the worth of our

small collection of books. There was no subject on which sufficient

information could not be got.

I divided my reading time

into four short sittings, varying the subjects, by advice of good Dr

Smith, to avoid fatigue, and as I slept little it was surprising how

many volumes I got through. It was "the making of me," as the Irish say;

our real mission here on earth had never been hinted to me. I had no

fixed aim in life, no idea of wasted time. To do good, and to avoid

evil, we were certainly taught, and very happy we were while all was

bright around us. When sorrow came I was not fit to bear it, and I had

to bear it all alone; the utmost reserve was inculcated upon us whenever

a disagreeable effect would be produced by an exhibition of our

feelings. In this case, too, the subject had been prohibited, so the

long illness was the consequence, but the after-results were good.

It was new to me to

think; I often lay awake in the early morning looking from my bed

through the large south window of that pretty "White room," thinking of

the world beyond those fine old beech trees, taking into the picture the

green gate, the undulating field, the bank of birch trees, and the Ord

Bain, and on the other side the height of the Poichar, and the smoke

from the gardener's cottage; wondering, dreaming, and not omitting

self-accusation, for discipline had been necessary to me, and I had not

borne my cross meekly. My foolish, frivolous, careless career and its

punishment came back upon me painfully, but no longer angrily; I learned

to excuse as well as to submit, and kissed the rod in a brave spirit

which met its reward.

My wise aunt found me a

new and profitable employment. She set me to write essays, short tales,

and at length a novel. I don't suppose they were intrinsically worth

much, and I do not know what may have become of them, but the venture

was invaluable. I tried higher flights afterwards with success when help

was wanted.

All this while, who was

very near us, within a thought of coming on to find us out, had he more

accurately known our whereabouts? he who hardly seven years afterwards

became my husband. He was an officer of the Indian army at home on

furlough, diverting his leisure by a tour through part of Scotland; he

was sleeping quietly at Dunkeld while I was waking during the long night

at the Doune. Uncle Edward, his particular friend, had so often talked

of us to him that he knew us almost individually, but for want of an

introduction would not volunteer a better acquaintance. It was better

for me as it was. I know, had he come to Rothiemurchus, Jane would have

won his heart; so handsome she was, so lively, so kind; a sickly invalid

would have had no chance. Major Smith and Miss Jane would have ridden

enthusiastically through the woods together, and I should have been

unnoticed. All happens well, could we but think so; and so my future

husband returned alone to India, and I had to go there after him! |