|

Upon the Queen’s

intended visit being certainly announced to the Marquess of

Breadalbane, the simple inhabitants throughout his wide territories

were excited to great and unusual speculation, by the ground

officers of districts visiting all the cottages and hamlets where

strong and active young men were to be found. Highland curiosity is

great as well as natural, and never was it more excited than upon

this occasion. Nor was it allayed when the first question asked was

met by important looks, and mysterious shakes of the head,

accompanying the reply that it was probable a gathering of the Clan

Campbell would soon take place; and that Lord Breadalbane desired to

know whether he could rely on their voluntary services, with kilt

and claymore, whenever he might summon them by the pipes or the

fiery cross. All without exception readily expressed their

willingness to assemble round the black and yellow gironied Bruttach,

and from that moment all work was suspended—the harmless tools of

rustic labour were left to rust, and arms that had for years lain

forgotten in remote corners of barns and outhouses, were carefully

sought out—blacksmiths were called into requisition—broadswords were

straightened and burnished up—all under the careful eye of some of

those ancient patriarchs, who having served in the gallant corps of

Breadalbane Fencibles, assumed the management of affairs, by

acknowledged right, and cocked their bonnets with a due

consciousness of their importance and experience in military

matters. But what could be the object of this gathering of the clan

in martial array? The Campbells had no feud in the country at that

moment; then, what could the object be? They scratched their pates,

stared at each other in silence, and listened with outstretched

necks to the various conjectures that were offered for the solution

of the question.

The people of a certain district were thus employed when they espied

a grave looking person, whom they knew to be a schoolmaster, going

leisurely along the road, on a shaggy shotten-necked shelty, and as

he was sometimes in the habit of solving any doubts that arose among

them, a circle was soon formed around him. Having been made

acquainted with the subject of their difficulties, he leisurely

unfolded and put on his spectacles, and drawing out of his pocket a

newspaper somewhat soiled, he slowly read a short paragraph from it.

Up went hats and bonnets into the air, and loud shouts of “Hurrah!

the Banrigh is coming to the Highlands! hurrah! hurrah!” were soon

heard resounding over the hill side. “But what hae they done to the

bonny Leddy?” demanded an old woman, after the noise had somewhat

subsided; “what hae they done till her, to gar her leave her ain

house, and come sae far north to the Balloch?”—“Wha has been fashing

her, Dominie?” demanded several angry voices, accompanied by looks

showing that the wearers of them would draw' the sword in her

cause.—“Nothing, nobody, my good friends,” answered the dominie;

“the Queen only wishes to see you, and will be here in a week to pay

you a short visit, after which she will return home to London.”—“And

its vera kind o’ her,” said a buxom housewife, whose curiosity had

led her to thrust herself amidst the deliberations of this council

of war; “but could she no hae letten us ken sooner, that we might

hae gotten time to make a’ things clean and ready? The lasses will

a’ be wantin new goons and braw claise; an’ I’m thinking that they

will no hae o’er muckle time at the Castle, to send awa a’ the

Sassenach painters wha hae been there sae lang, wi’ their brushes

and pots, an’ bit bukes o’ gowd leaves they are stiekin’ against the

wa’s, and to put the chairs and tables right into a’ the rooms

again, forbye makin’ preparations in the kitchen.” — “Haud yer

tongue, woman,” said her husband; “preparations!—Is there no deer

and grouse on the hills,—breachcan in the loch,—sheep and stots in

the pastures,—and plenty o’ gude wine, whisky, and yill in the

Balloch cellars?—An’ the Banrigh comes to the Hielants, she maun be

contentit wi’ Hielant cheer and Hielant welcome; and I’se warrant ye

she’ll get baith in plenty, an’ she would come this verra nicht.”—This

dialogue, obtained from an unquestionable authority, affords a

better idea of the spirit of loyalty and affection for the Queen

prevailing in the Highlands, than any graver disquisition could

convey; and how far this man was right in his conjecture, that there

would be no lack of food at Taymouth during the time of the Queen’s

visit, may be imagined from the fact, that about seven hundred and

thirty persons were daily fed in and about the castle. One zealous

Highland friend of the Marquess remarked, that “Breadalbane was

certainly right to give his countenance to the Queen when she

visited the north; but,” added he, shaking his head, “it will cost

him a hantel o’ siller.”

Now that the news of the Queen’s approaching visit became publicly

known, nothing was to be seen on all sides but active and busy

preparation, and the Highlanders laboured with a zeal which proved

that, short as the notice had been, they were anxiously resolved to

receive their young Sovereign in a manner worthy of her and of

themselves. In the villages of Aberfeldy and Kenmore, the houses

were white-washed, and ornamented with wreaths of heather and

evergreens, and tasteful triumphal arches, with devices and mottoes,

were erected, as well as on various parts of the roads in the

Taymouth pleasure grounds, and especially on the bridge leading

across the burn on the approach to the castle, and on that over the

Tay at Kenmore, where there was a very grand one The cannon of the

several batteries were examined, and put in ei ;nt order, and men

having been trained to serve them, they were ut under the command of

Captain MacDougall, R.N.—the chief of Ma Dougall and Lorne—to whose

charge the flotilla of boats, with their crews, were also committed.

An encampment of tents was pitched in that beautiful flat piece of

grass within the fork formed by the river Tay and its junction with

the burn, immediately opposite to the Star battery.

Few now had any rest, and trades-people were especially well worked.

The tailors, in particular, were seen running hither and thither

like startled hares, almost bereft of reason, from the difficulty

they had in determining whom they should first serve, and to what

they should first begin. Lowland drapery of all kinds was despised,

and the demand for kilts was immense. The bustle was so excessive

among the younger and middle-aged, and the news that the Queen was

coming to Breadalbane so surprising, that the elders of the various

districts could hardly assure themselves that they were awake.

Pipes were heard at a distance. The sounds approached;—became

gradually more distinct, and were finally recognised as the Clan

March, “The Campbells are coming,” which announced the arrival of

sixty stout athletic volunteers, from the far western isles,

belonging to the Breadalbane estates. Again and again the same

shrill notes were heard from different quarters of the compass, and

other detachments of the clan appeared in view, and poured down the

hills in every direction, marching towards Taymouth as to a common

centre, from Glenurquhy, Lornc, Ivillin, Aberfeldy, Glenquaich,

&c.,—all marshalled by their respective pipers. Two hundred

volunteers were now picked out, and proud was each man of being

selected to form a Highland guard of honour for the Queen. It had

been perfectly understood that it should consist solely of men who

volunteered their gratuitous services, and that they were to have no

allowance,' except for their personal expenses in their journey to

and from Taymouth, and their board whilst there. Lord Breadalbane

had in contemplation to have given each man a medal, struck

expressly in commemoration of the occasion, but a desire having been

manifested on their part, rather to retain and preserve their

uniforms, his Lordship acceded to their wishes. The men were,

divided into companies, and officered by gentlemen of the clan.

Drilling was actively prosecuted, and they very soon attained

sufficient knowledge and expertness to enable them to form a compact

and imposing battalion, the organization and equipment of which was

completed by the distribution of the clothing prepared for them by

order of the Marquess. Four of the companies, mustering 126 in all,

were dressed in kilts and plaids of the green Breadalbane tartan,

coats of rifle-green cloth, Rob Roy hose, blue bonnets, with the

Campbell’s crest, a boar’s head, in silver, and their badge, a sprig

of that well-known sweet-scented shrub called Merica Gale, or as it

is commonly called, Highland Myrtle, a complete set of belts,

buckles, and brooches, and a claymore. In addition to all these

things, the grenadier company, forty strong, had round Highland

targes, studded with brass ornaments; and a body of twenty-four men,

also dressed and equipped in the same way, were armed with Lochaber

axes, halberds, and targes. The light company, thirty strong, was

composed entirely of foresters and gamekeepers, who were somewhat

differently dressed. Their kilts and coats were made of that small

black and grey check, now known by the name of shepherd’s tartan,

and which is in fact nothing more than a degenerated Douglas tartan—Dhu-Glass—black

and grey, which came to be common on the Borders, from the sway

which that proud family had there, and which has been since

transplanted into the Highlands, from the Lammermoors and Cheviots,

with the Cheviot sheep, and the Border shepherds who came to take

care of them. The hose and bonnets of the light company were also of

a grey colour, but their plaids were of the same green Bread-albane

tartan as those of the other companies. Besides the claymore, they

were armed with rifles, slung across their backs. In addition to

these, there were thirty sailors belonging to the flotilla on the

lake, dressed in white trowsers and Breadalbane tartan frocks, and

caps with gold bands. Being thus finally equipped, they were

officered as follows :—

Colonel in Chief, The Marquess of Bredalbane.

Lieutenant-Colonel, William John Lamb Campbell of Glenfalloch.

Grenadiers, Captain Charles William Campbell of Boreland.

Light Company, Captain George Andrew Campbell of Edinample.

First Centre Company, Captain William Bowie Stewart Campbell of

Clochfoldach.

Second Centre Company, Captain John Renton Campbell of Lamberton.

Third Centre Company, Captain Francis Garden Campbell of Glenlyon.

Lieutenant of Grenadiers, Captain William Campbell of Auch, late

3Sth Regiment.

Halberdiers and Lochaber-Axe Men, Sir Alexander Campbell of

Barcaldine, Bart.

Adjutant, Major Campbell of Melfort.

Second Adjutant, Captain David Campbell, late 91st Regiment.

Principal Standard-Bearer, John Alexander Gavin Campbell, younger of

Glenfalloch.

Military Secretary, J. W. De Satrustequi, Knight of St. Ferdinand.

Loch Tay Flotilla.—Commodore, Captain MacDougall of Lorne, R.X.

Second in Command, Lieutenant Campbell of Daherf, R.X.

Flag-Lieuteuant, Lieutenant Patrick Campbell, R.X.

They were then reviewed by Lord Breadalbane, who afterwards

addressed them in an eloquent speech, explained the duties they had

to perform, and expressed his lively satisfaction at their excellent

appearance, and his thanks for their having come voluntarily to

assist him in receiving the Queen in a manner worthy of the

Highlands; and for the convincing proof they had thereby given him,

that those feelings of loyalty to the Crown, and attachment to their

chieftains, which animated their forefathers, continued as strong as

ever in the glens and on the mountains of Scotland.

Although much had been done before the 7th of September, yet the

morning sun of that day, which rose somewhat mistily at first, found

every one at Taymouth fully occupied. The Marquess was planning and

directing every thing; and both in and about the castle, and

throughout the whole of the grounds, hundreds of workmen were busily

employed in getting things into perfect order. Men were seen in

different directions mounting ladders, loading the boughs of the

trees with coloured lamps, and hanging thousands of them along the

high wire fence running across the park at some distance in front of

the castle, and arranging them in proper form on that steep line of

bank already described as rising from the lawn to the westward of

the building. Tents had been pitched on the open glade within the

eastern gate, for the detachment of the 92d Highlanders. Particular

posts and duties were assigned to individuals, yet the Marquess

frequently appeared beside them, to make sure that his directions

were strictly followed. From an early hour in the morning, a \ast

multitude of people of all ranks, many of whom had come from great

distances, continued to pour into the park, the gates of which had

been thrown open to all classes. The major part of the tenantry, and

of the inhabitants of the surrounding districts, were dressed in

tartan, the gay and variegated hues of which contrasted agreeably

with the more sober coloured garments of the strangers from the

lowlands, most of whom, however, seemed to have adopted something of

the kind; and where nothing better could be had, heather sprigs were

stuck in their hats or bosoms, by way of enabling' them to show some

link of connection with the Highlands, howsoever slender. Early as

these good people were upon the ground, they had no lack of pleasure

or amusement, whilst walking about indulging in admiration of the

beauty of the place, and the grandeur of the surrounding

scenery—listening to the music of the band of the 92d regiment

playing on the lawn, and watching the busy bustle of preparation.

Meanwhile the Breadalbane banner, with its girony sable and or, was

floating from the highest part of the western tower of the castle,

where two Admiralty bargemen, in their gorgeous crimson dresses, and

with their great silver badges on their arms, were all day

stationed, like two ancient warders, to be in readiness to haul down

the Breadalbane flag and hoist the Royal standard when the Queen

should arrive. On the Gothic balcony, stretching along the front of

the great central mass of the house, stood Captain MacDougall of

Lorne, R.N., the chief of the Mae-Dougalls, in his full Highland

dress, and wearing the celebrated brooch of Lorne. He had in charge

a Royal standard, and four flags of the old Breadalbane Fencibles

were borne by Highlanders placed at regular intervals on the

balcony, giving it an extremely rich appearance. A banner, 40 feet

long by 36 feet broad, was flying on the top of Drummond hill, from

a flag-staff made of the tallest pine that could be procured, and

yet, at that elevation, it looked like a pocket-handkerchief on the

end of a walking-stick. On the highest points of the Braes of

Taymouth, lofty flag-staffs had been erected, from which fluttered

large standards, emblazoned with the family quarterings; the fort

and batteries were also decorated with flags, and crowned with

artillerymen. Amidst all this, the scene became every moment more

animated. Gaily dressed ladies, and Highland gentlemen, in the

splendid and jewelled garbs of their respective clans, were seen

lounging along the shady avenues, the verdant, mossy terraces, by

the margin of the bright stream of the broad Tay, or standing in

crowded groups within the velvet lawn, or, as they walked across it,

startling the deer into retirement beneath the lofty and spreading

trees. Highland lasses in their white dresses, tartan scarfs, and

with snooded hair, were seen concentrated in numbers on the bank to

the westward of the castle, vainly endeavouring to attract the

attention of their sweethearts, who, strutting about like peacocks

in the pride of their dress, were too much occupied with themselves,

and the greatness of the occasion, to be assailable b\ the glances

thrown around them.

The different guards of honour were now arranged in a hollow square

on the gravel, in front of the castle. The principal entrance hall

itself was lined by that body of gigantic Highlanders armed with

shields and huge Lochaber axes, commanded by Sir Alexander Campbell

of Barcaldine, whose portly figure towered high above those

Philistines. On each side of the arched doorway, and in a line with

the ivy-covered arcades running along and covering the base of the

building, were extended the targemen of the Breadalbane Highland

Guard of Honour. Immediately opposite to the principal entrance, but

at a considerable distance from it, and facing towards it, the

detachment of the 92d Highlanders was stationed with their colours,

and on their right and left wings were the second and third

companies of the Highland Guard, their lines being a little more

advanced. The western face of the square was formed by the light

company of foresters, with their rifles, and that opposite to them

by the first centre company of the Highland Guard, who filled the

ground as far as the carriage entrance to the gravel from the east;

and between that and the castle, the space was occupied by a

squadron of the Carabineers, that arrived about mid-day. Within the

square, and a little in advance of the 9'2d Highlanders, twelve

pipers, richly dressed in the full Highland costume, stood in two

divisions, their pipes ornamented with streamers, and having

embroidered flags, bearing the Breadalbane quarterings. Upon the

grass of the lawn, at some distance behind the 92d, was placed the

band of that regiment, surrounded still farther back by a large

crescent, formed by the boatmen of the Loch Tay flotilla, dressed in

frocks and caps of the family tartan, with white trousers, and

bearing the banners of their boats. In rear of these there was a

long line of Highlanders of different clans, dividing off the

general mass of spectators from those of a higher rank. In the

centre of the hollow square stood Lord Breadalbane, in a superb

Highland dress of velvet tartan, covered with rich ornaments and

jewels, and wearing on his head the graceful bonnet of a chieftain,

surmounted by a heron’s plume. He was attended by the Hon. Fox

Maule, Campbell of Glenfalloch, and by several other gentlemen,

doing the duties of staff-officers, all in richly ornamented

Highland dresses. The rest of the officers of the Highland guard

stood in line, three paces in advance of their respective companies,

and alternating with the numerous standard-bearers, who supported

silken banners, and swallow-tailed pennons of blue, white, yellow,

and green, emblazoned with the quarterings and bearings of

Breadalbane. At the head of these was young Campbell of Glenfalloch,

who bore the standard of the Marquess.

Early in the day Sir Neil Menzies of Menzies, Bart., as chief of his

clan, appeared at the head of about thirty of his men, with six

pipers playing before him. He was mounted on a white pony, and

attended by his eldest son. The bright and gay red and white Menzies

tartan had a fine effect, in contrast with the dark green of

Breadalbane. They carried two banners, the one bearing the Menzies

arms, and the other the words, “God Save the Queen,”— both were made

of white satin. They had sprigs of heather in their bonnets, and

they took up their position on each side of the entrance to the

square of gravel, lining it for a long way eastward. Truly it was a

grand and glorious sight to see so great an assemblage of these

hardy sons of the mountains, magnificent looking men, all dressed

and armed as their forefathers wont to be! And how gratifying was

the thought that they were not congregated like eagles in the

anticipation of slaughter, as was too generally the case in former

times. They came, urged by the strongest feelings of loyalty, and of

more than loyalty—of love to their Queen, generated in their minds,

by the knowledge of her private and domestic virtues, which came

home to the comprehension and the heart of the humblest Highlander,

who, though perhaps careless to a fault about all those great

abstract political questions dividing his Lowland brethren into

Whig, Tory, and Radical, is a deep inquirer into every thing

relating to the moral conduct of those by whom he is governed.

Perhaps he was less so in some earlier periods of our history, when

his loyalty to his true prince might have been impaired by too close

a scrutiny; yet his composition is such, that the affectionate

devotion of his heart is only to be fully secured by those whose

exemplary domestic virtues are in harmony with his own.

A man was placed by Sir Neil Menzies on the hill of Dull, where

there was a pile of wood for a bonfire, whence he could command a

view of the Strath of Tay. He was furnished with a glass, and

instructed to hoist a flag whenever the Queen came in sight. This

hill was visible from the front of the castle at Taymouth, and

hundreds of spectators stood for hours gazing on the black speck

where the expected signal was to be given. Two o’clock came—three

o’clock—four o’clock—and still no signal, and numerous were the

speculations hazarded, while many declared that it was evident the

man had neglected his duty, and that the Queen must be in sight.

Between four and five o’clock a carriage and four rattled up to the

door, with Lord and Lady Kinnoull, and their daughter Lady Louisa

Hay, who were overwhelmed with inquiries, producing the information

that the Queen was at Dunkeld, and would be up in about an hour.

Then came anxieties and fears, that Her Majesty might be too late

for the scenery, the heavens having by this time so far altered,

that the brilliant sunshine had given place to a dullish grey sky.

At last, about five o’clock, to the joy of all, the signal was

descried on the hill, and then all was quietness. The certainty of

the Queen’s speedy arrival, induced every one to take his own place,

if he had one, or to look out for a good situation if he had not;

and all now waited in the breathless silence of expectation. The

Marchioness now descended to the entrance-hall to receive the Queen,

her elegant and sylph-like figure pleasingly contrasting with the

huge forms and swarthy features of the Lochaber-axemen who

surrounded her.

At twenty minutes to six o’clock, a cheering, and then a bugle

blast, in the direction of the great eastern gate, excited

attention, and immediately afterwards the Queen’s carriage was seen

approaching with its escort, and, by Her Majesty’s own command, at a

slow pace, that she might have leisure to contemplate the scene,

which was indeed magnificent. The approach is partly covered by

trees, so that the train of carriages and cavalry were at first only

seen at intervals, but it crossed the bridge under the triumphal

arch, and approached so slowly, that all present had a perfect view

of the Queen. When the Royal carriage drew nigh, and the heads of

the leaders had come within the square of gravel, the deep silence

was broken b} Lord Breadalbane’s loud command— “Highlanders, prepare

to salute!” "With one simultaneous jerk, the sword arms were fully

thrown forward, with the claymores held vertically, and with their

points upwards. The carriage advanced towards the great door, and

his Lordship gave the second command—“Salute!” at which every

claymore, slowly describing a semicircle, presented itself with the

point downwards, the Highlanders at the same time raising the edge

of their left hands to their foreheads. The standards and peunons

were lowered to the ground. The 91st regiment presented arms—their

band playing “God Save the Queen!” The pipes struck up the Highland

Salute, and the Marquess ran nimbly round the horses’ heads to the

right door of the carriage, to assist the Queen to alight. The Queen

shook Lord Breadalbane warmly by the hand, as did also Prince

Albert. Lady Breadalbane then stepped forward to make her obeisance,

when Her Majesty saluted her in an affectionate manner. The Marquess

then presented some sprigs of the Highland myrtle to the Queen,

saying, “As your Majesty has done me the high honour of coming to

Taymouth, may I beg that you will deign to accept from my hand the

badge of the clan Campbell.” This the Queen received most

graciously, and Lady Breadalbane presented the same to the Prince.

The Queen remained at the door for a few minutes, bowing to the

distinguished persons who stood uncovered on the Gothic balcony

above, and graciously acknowledging the joyous acclamations of the

assemblage in front, and exclaimed, “How grand this is!” And if the

combination of the features of nature, the works of art, and the

animation of human life, by which the Queen was surrounded, was

enough to call forth such an expression of admiration from Her

Majesty, whose eyes had been from infancy accustomed to grandeur,

what must it have been to those of the masses who had never beheld

any thing like it before, and to whom she herself was the great

point of attraction!

The Queen now entered the castle, and at that moment the two

Admiralty bargemen stood ready on the western tower to lower the

Breadalbane flag from the flag-staff, and to hoist the Royal

standard in its place, which was done amidst the loud cheers of a

hearty welcome from Celt and Southron on the lawn, whilst the fort,

high up among the towering woods in front, was blazing away in a

royal salute, and the two batteries in the valley below were

answering it, producing one continued roar of thunder all around the

hills, which ran up the trough of Loch Tay, ruffling its pellucid

mirror, and roused the distant echoes of Benlawers.

As the Queen passed between the files of the chosen halberdiers who

lined the entrance hall, she turned and said, “What fine looking

Highlanders!” Her Majesty then ascended the grand stair and entered

the drawing-room, in which were assembled some of the most

distinguished nobility. Among these were—the Duchess of Sutherland,

with her daughter Lady Elizabeth Gower, the Duke and Duchess of

Buccleuch, the Duke and Duchess of Roxburghe, the Marquess and

Marchioness of Abercorn, the Marquess of Lorne, the Earl and

Countess of Kinnoull and Lady Louisa Hay, the Earl of Morton, the

Earl of Aberdeen, the Earl of Lauderdale, the Earl of Liverpool,

Lord and Lady Belhaven, the Hon. Mr. and Mrs. Fox Maule, and others.

Her Majesty saluted the Duchess of Sutherland, and shook hands with

Lady Elizabeth Gower, and the Duchess of Roxburghe; and having

received the homage and compliments of the rest of the party, she

went out on a platform, covered with crimson cloth, on the Gothic

balcony, accompanied by Prince Albert, and attended by Lord and Lady

Breadalbane and a numerous retinue. On the Queen’s right stood the

chief of MacDougall, with a royal standard in his hand, which

floated over Her Majesty’s head. At first the Queen had somewhat of

an air of lassitude, but she had not looked for a moment at the

splendid scene before her, until its animating effect filled her

eyes with delight. The band and the pipers were still playing—the

guns were still firing— the thunders of the mountains were still

running their tremendous round, so that the cheers of the assembled

multitude were scarcely heard, though the commotion made in the air,

by the upheaving of caps and bonnets, and the whirling of

handkerchiefs, scarfs, and shawls, was sufficiently apparent to

testify the exuberant joy of those loyal sons and daughters of the

mountains. Her Majesty seemed much affected, and bowed with the

greatest cordiality of expression. And what a sight it was to see

that magnificent array!—their arms glancing in the sober light of

evening, which was already embrowning the wooded hills in front of

the castle, from whose face successive flashes of the red artillery

were pouring,—whilst their summits were half veiled by the curling

smoke dispersing itself over them! The whole of this reception was

considered by the Queen as the finest thing she had seen in

Scotland. Returning into the drawing-room, Her Majesty retired to

her private apartments, and having done so, she gave way to the

natural impulse of her heart, and despatched a letter to her royal

mother the Duchess of Kent.

The banquet was laid in the Baron’s Hall, whose, Great Gothic

window, rich in the portraits of Breadalbane ancestry, as well as in

its heraldry, being illuminated from without, had a gorgeous effect.

From the vaulted roof were suspended massive antique Gothic

lanterns, throwing a rich and subdued light upon the royal table,

laid for thirty covers, and loaded with a dazzling profusion of gold

and silver plate. The sideboards and cabinets were all groaning

beneath the weight of splendid gold and silver vases, cups, and

salvers, richly chased and of the most elegant designs, and many of

them of the most curious and elaborate workmanship. Every variety of

the most delicate viands, and of the choicest wines and fruits, were

served to the Royal party by a host of retainers in gorgeous

liveries, whilst the band, and the pipers without, were alternately

executing their various pieces of music. In addition to the Queen

and Prince Albert, and their noble host and hostess, the Royal party

this day consisted of—

The Duchess of Norfolk,

The Earl and Countess of Kinnoull,

Lady Louisa Hay,

Sir Robert Peel,

Lord and Lady Belhaven

The Hon. Sir Anthony Maitland,

The Hon. Miss Paget,

General Wemyss,

Colonel Bonverie,

Mr. George Edward Anson,

Sir James Clark.

The Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch,

The Duke and Duchess of Roxburghe,

The Duchess of Sutherland,

Lady Elizabeth Gower,

The Marquess and Marchioness of Abercorn,

The Marquess of Lorne,

The Earl of Liverpool,

The Earl of Morton,

The Earl of Aberdeen,

The Earl of Lauderdale,

The Queen was cheerful and happy, and condescended to talk very

agreeably with those around her. In addition to the royal table, two

others had been laid in different apartments, at which sat the

officers of the Highland Guard, and the numerous visitors that

filled the castle.

The Queen and the ladies having left the dining-room, and the Prince

and the gentlemen having followed in a few minutes after, the other

guests in the house joined the party in the drawingroom. The crowds

who had continued to maintain their places without, were rendered

unconscious of the transition from day to night, by the brilliant

illumination which gradually produced its effects as the darkness

came on, the gay lights of myriads of coloured lamps converting the

twilight into noonday, and burning with increasing splendour, as the

shadows of approaching night grew broader and deeper. It seemed as

if a magician’s wand had realized the fabled splendours of the

Arabian Tales. The trunks of the trees were converted into

picturesque and irregular columns of fire, and their branches became

covered with clusters of sparkling rubies, emeralds, topazes, and

diamonds, like the fairy fruit in the ideal gardens of the genii.

The variegated lamps, hung along the wire-fence of the deer park in

beautiful festoons, presented the appearance of an unsupported and

aerial barrier of living fire. The architectural bank of turf which

has been more than once mentioned, as being a little to the west of

the front of the castle, but nearly opposite to that part containing

the Queen’s apartments, exhibited on its sloping front, in many-coloured

lamps, and in the following form, the

words—“Victoria,”—“Welcome,”—“Albert,”—and these, and the other

figures and devices which strewed the lawn, looked like dew-drops

touched by the beams of the sun, and scattered abroad by some fairy

illusion. On the grassy slope of the face of the hill, the letters

V. and A., with a crown between, of the most gigantic proportions,

illumined all the trees and bushes surrounding that falling glade.

The fort among the woods above, and the tall crenelled cylindrical

tower, still higher up, were blazing with resplendent golden light.

The fort was especially beautiful. It had about 40,000 lamps upon

it, and it was metamorphosed into a Turkish pavilion, with the

crescent on each wing; and a representation of the girony of eight

pieces—or, and sable, produced by lamps—surmounted the centre. Ever

and anon the flash of a gun gave additional though momentary

splendour to the woods, and the boom of its report ran in sublime

echoes around the whole sides of the valley. Above all, the whole

tops of the northern hills were crowned with immense bonfires, of

which countless numbers were visible in all quarters around the

valley, so that the rugged outlines of the most distant mountains in

the background were rendered visible by their own volcanic-looking

flames. To all these blazing and sparkling wonders, the intense

darkness of the night gave additional effect. The world has, no

doubt, seen many such splendid illuminations, but it is very

questionable if anything so true magnificent, romantic, and

fairy-like, ever was produced by the hands of man, or ever could be

produced, except in some place possessing the same grandeur, and

beauty, and aptitude of natural features as are to be found at

Taymouth; and it requires no great boldness to affirm, that such a

place is not always to be met with. To those who had the good

fortune to be there at the time, it immeasurably outdid all those

magic visions created in young imaginations by those writers of

eastern tales, whose inventions are devoured with so much avidity.

The mind, indeed, was almost bewildered with the sight of the

reality, so that it is no wonder that the endeavour to convey some

idea of it in mere words, should prove weak and inefficacious. Hut

this was not all,—for precisely at ten o’clock, a regular salute

from the battery announced the commencement of the fireworks. These

were of the very highest style of excellence that the pyrotechnical

art could produce. They were displayed from the abruptly sloping

lawn that hangs towards the base of the hill, directly across the

park in front of the house. The flights of rockets were magnificent,

shooting up in fiery phalanxes to mingle with the very stars, and to

give momentary extinction to their brightness. There were green,

blue, and red lights in abundance, and in every variety of design ;

and at one time the fort had a transparent purple flame thrown over

it, succeeded by a brilliant green light, that was like the work of

some magician. All manner of curious and astonishing freaks and

fancies were performed by fire, and most of the devices had some

allusion to the Queen or Prince Albert, whose names were suddenly

produced in fiery sparks of every possible hue. One splendid effect

was created by the sudden evolution of a grand triumphal arch from

the midst of a blaze of light, crowned by the words “Long live the

Queen!” in large and brilliant letters, which produced deafening

cheers from the spectators. There were many honest citizens of

London present, who had seen the glories of Vauxhall, and who

declared that the) were all utterly extinguished by those of this

single night at Taymouth ; and if this was the case with the few

Londoners who were there, what must have been its effect on the

unsophisticated Celts, many of whom had never left their own

district? But it is a part of the character of a Highlander, as it

is of that of the North American Indian, never to permit himself to

be astonished at anything ; and there is a greatness in this

self-control.

The Queen enjoyed much of this spectacle

of matchless splendour from the windows of her own private

apartments, after which Her Majesty returned to the drawing-room.

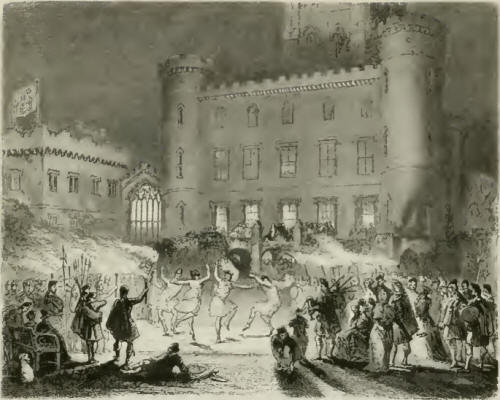

Two large wooden platforms were then brought out in front of the

castle. These were raised about a foot from the ground, to give them

spring. At each corner, one of the Clan Campbell Highlanders

supported a standard, and there too were placed colossal Celts,

bearing torches, that threw a strange glaring light on the serried

phalanx of tartan figures surrounding three sides of the platforms,

together with those forming the lane kept open as a communication

with the great entrance. On these stages commenced a series of

Highland reels, in which some of the most active dancers performed

their wild and manly steps to the shrill and spirit-stirring notes

of the bagpipes, their whole action being rendered more picturesqne

by the red glare flaring and flashing from the torches, and more

interesting by the joyous shrieks of the performers and spectators.

Lord Breadalbane and Mr. Fox Maule stood by directing and

encouraging, and the torches were ordered to he held lower, for the

purpose of showing off the steps. Whilst to those without the

castle, the whole of its interior appeared in a blaze from the

intensity of the light within it, which showed the great painted

Gothic windows of its hall, in all their rich and harmonious tints,

so it had the effect of dimming external objects to those looking

out; and as the Queen began to take great interest in the dancing,

she bid defiance to the damp and drizzling air—and a chair being

placed on the platform, she went out on the balcony, with a cloak on

her shoulders, and a small scarf thrown over her head. Although the

platform was dry, it was raining slightly, and one of the ladies

held a parasol over Her Majesty’s head. But the balcony itself was

wet, and some of those present thought that the Royal experiment was

so hazardous, that they noticed it to Sir James Clark, the Queen’s

physician, who replied, that as long as Her Majesty’s feet were kept

dry, there was no danger. The appearance of the Queen on the balcony

was hailed by deafening cheers, and a new spirit was infused into

the scene. As the dancing went on, it was found that there was still

a want of light on the stages, and large house lamps were carried

out, which had the desired effect. One of these, however, was soon

demolished, by a more than ordinarily energetic fling from one of

the dancers, but as no one suffered from this accident, it only

produced a laugh. The performers made great efforts to excel, and

they were watched with extraordinary interest by their fellows, who

looked on. The rill Thullachan was danced with the greatest spirit,

and one man who executed Gillum-Callum very neatly over the cross

swords, was highly applauded. A very old man of the Clan Menzies,

also danced extremely well, considering his age. After several reels

by the men of the Highland corps, the Hon. Fox Maule, and some of

the officers, filled the platform for one reel, and performed it

with great spirit, energy, and grace, eliciting in a marked manner

the smiles and approbation of Her Majesty, and loud cheers from the

surrounding Highlanders.

The Queen was so much amused and interested by the whole scene of

the dancing, which was not only curious in itself, but extremely

pictorial in its effects of light and shadow, that, notwithstanding

the very disagreeable nature of the evening, she maintained her

position on the balcony for about an hour. Her Majesty and the

Prince watched the fine attitudes and the agile pirouettes of the

performers, with surprise and admiration, as, transported with

excitement, their animating shouts were re-echoed by loud

acclamations from the spectators. The wet, which could not dim the

lights, had no effect in damping the ardour of the dancers, and the

broad glare spread over the wild countenances of those nearest to

the stages, growing fainter as it receded among those behind, and

leaving the dark masses of the great crowd still farther off, with

no other illumination than such as partially fell on them from the

house, or from the coloured lamps in the trees, imparted to the

whole scene a most extraordinary and striking character. When the

Queen was in the act of quitting the balcony, she was again loudly

cheered. The Prince disappeared with Her Majesty, but he returned to

the balcony, and continued to enjoy the lively scene below for some

time longer.

The Queen and the Prince retired soon afterwards to their private

apartments—the castle clock tolled the hour of midnight—and although

the Highlanders were so well warmed with whisky, as to be loth to

depart, they yet voluntarily dispersed immediately, entirely from an

innate sense of propriety, and, as some of themselves said, “That

their bonny Queen might sleep in undisturbed silence and

tranquillity.” Many of them, doubtless, were contented with the

heather for their bed, and the heavens for their shelter. The duty

of watching over the Queen’s safety, which belonged to the 92d

Highlanders, was, by Her Majesty’s especial command, shared with the

Breadalbane Guard; and their vigilant sentinels surrounded the

castle with so loyal a care, that even the officers, silently

patrolling from time to time, had the pointed claymore presented to

their breasts until they made themselves known.

Many were the whimsical scenes that occurred in Kenmore, Aberfeldy,

and the hamlets and houses of the surrounding districts, from the

crowds of strangers that besieged them for beds. Every floor was

covered with shakedowns, and for each of these a charge of from ten

shillings to a sovereign was made; and many were glad to content

themselves with a chair to sit up in. The scramble for food next

morning was no less than it had been for beds, and many who had

never tasted porridge in their lives before, seized upon the wooden

bicker that contained it, and were fain to gobble it up with the

help of a horn spoon. It was pleasant to see, however, that all

these inconveniences were borne with good humour, every one

declaring that a sight of the glories of Taymouth would have been

cheaply purchased by deprivations and hardships of tenfold greater

magnitude. And, indeed, they were glories, such as, when taken

together with the magnificence of the natural theatre where they

were exhibited, are scarcely to be paralleled. The revelries at

Kenilworth, in honour of Elizabeth, were sufficiently gorgeous; but

rich as is the district in which they took place, it can no more be

compared, in point of romantic effect, with that of the bold wooded

mountains, the variegated plains, and the sparkling streams of

Taymouth, than the homely countenance and ascetic expression of the

Queen who was a guest there, can be thought of in comparison with

the lovely face that shed its smiles this night on all within the

noble castle of the Marquess and Marchioness of Breadalbane. |