|

DRUMMOND,

a surname derived originally from the parish of Drymen, in what is now the

western district of Stirlingshire. The Gaelic name is Druiman,

signifying a ridge, or high ground. One of the Scottish clans, which, like

the Gordons, resided on the borders of the Highlands rather than in the

Highlands themselves, possessed this surname, and their particular clan

badge, anciently worn as the distinguishing mark of the chief, was the

holly.

The origin of

the Drummonds is traditionally traced to a nobleman of Hungary, named

Maurice, who is said to have accompanied Edgar Atheling and his two

sisters to Scotland, in 1068, when they fled to avoid the hostility of

William the Conqueror. The vessel which contained the royal fugitives was

piloted by this Maurice, but was cast, by stress of weather, on the coast

of Fife. They were received with royal munificence by Malcolm Canmore, who

married Margaret the elder of the two princesses, and conferred on the

Hungarian Maurice large possessions, particularly Drymen or Drummond in

Stirlingshire, from whence his descendants took their surname. This

Maurice was the progenitor of the earls of Perth. [See PERTH, earl of.] He

was by Malcolm Canmore appointed seneschal or steward of Lennox.

An ancestor of

the noble family of Perth thus fancifully interprets the origin of the

name: Drum in Gaelic signifies a height, and onde a wave,

the name being given to Maurice the Hungarian, to express how gallantly he

had conducted through the swelling waves the ship in which prince Edgar

and his two sisters had embarked for Hungary, when they were driven out of

their course, on the Scottish coast. There are other conjectural

derivations of the name, but the territorial definition above-mentioned

appears to be the correct one.

The chief of the

family at the epoch of their first appearing in written records was

Malcolm Beg, (or the little) chamberlain on the estate of Levenax, and the

fifth from the Hungarian Maurice, who married Ada, daughter of Malduin,

third earl of Levenax, by Beatrix, daughter of Walter lord high steward of

Scotland, and died before 1260.

Two of his

grandsons are recorded as having sworn fealty to Edward the First.

The name of one

of them, Gilbert de Dromund, “del County de Dunbretan,” appears in

Prynne’s copy of the Ragman Roll. He was Drummond of Balquapple in

Perthshire, and had a son, Malcolm de Drummond, who also swore fealty to

Edward in 1296, and was father of Bryce Drummond, killed in 1330 by the

Monteiths.

The other, the

elder brother of Gilbert, named Sir John de Dromund, took the oath to

Edward, by an obvious compulsion, as he was the same year carried prisoner

to England, and confined in the castle of Wisbeach, but was released in

1297, on condition of serving Edward against the French. He married his

relation, a daughter of Walter Stewart, earl of Menteith, and countess in

her own right.

His eldest son,

Sir Malcolm de Drummond, attached himself firmly to the cause of Bruce,

and about the time of his father’s death, he was taken prisoner by Sir

John Segrave, an English knight; on hearing which “good news” Edward, on

25th August 1301, offered oblations at the shrine of St. Mungo,

in the cathedral church of Glasgow. King Robert, after the battle of

Bannockburn, bestowed upon him certain lands in Perthshire. Sir Robert

Douglas thinks that the caltrops (or three-spiked pieces of iron, with the

motto, “Gang warily”) in the armorial bearings of the Drummonds, afford a

presumption that Sir Malcolm had been active in the use of these

formidable, and on that occasion very destructive, weapons. In the

parliament held by Bruce in 1315 at Ayr, he sat as one of the great barons

of the kingdom. He married a daughter of Sir Patrick Graham of Kincardine,

elder brother of Sir John Graham, and ancestor of the family of Montrose.

He had a son, Sir Malcolm Drummond, who died about 1346. The latter had

three sons, John, Maurice, and Walter. The two former married heiresses.

Maurice’s lady

was sole heiress of Concraig and of the stewardship of Strathearn, to both

of which he succeeded.

The wife of

John, the eldest son, was Mary, eldest daughter and co-heiress of Sir

William de Montefex, with whom he got the lands of Auchterarder,

Kincardine in Monteith, Cargill, and Stobhall in Perthshire. He had four

sons, Sir Malcolm and Sir John, who both succeeded to the possessions of

the family; William, who married Elizabeth, one of the daughters and

co-heiresses of Airth of Airth, with whom he got the lands of Carnock; and

from him the Drummonds of Carnock, Meidhope, Hawthornden, and other

families of the name are descended; and Dougal, bishop of Dunblane about

1398; and three daughters, namely, Anabella, married, in 1357, John, earl

of Carrick, high steward of Scotland, afterwards King Robert the Third,

and thus became queen of Scotland, and the mother of David, duke of

Rothesay, starved to death in the palace of Falkland, in 1402, and of

James the First, as well as of three daughters; Margaret, married to Sir

Colin Campbell of Lochow; Jean, to Stewart of Donally, and Mary, to

Macdonald of the Isles.

A portrait of

Queen Annabella is given in the second volume of Pinkerton’s Scottish

Gallery, taken from a drawing in colours by Johnson, after Jamieson, in

the collection at Taymouth. Pinkerton thinks it probable that Jamieson had

some archetype from her tomb at Dunfermline, or some old limning. A

woodcut of it is given below.

[woodcut of Anabella Drummond]

From the

weakness and lameness of her husband, Queen Annabella had considerable

influence, and supported the whole dignity of the court. Her letters to

Richard the Second of England have been printed in the Appendix to volume

I. of the History of Scotland, under the Stuarts. London, 1797, 4to.

Fordun states that Annabella, and Traill, bishop of St. Andrews, managed

with eminent prudence the affairs of the kingdom; appeasing discords among

the nobles, and receiving foreigners with hospitality and munificence; so

that on their death is was a common saying that the glory of Scotland was

departed. They both died in 1401.

In May 1360, in

consequence of a feud which had long subsisted between the Drummonds and

the Menteiths of Rusky, a compact was entered into at a meeting on the

banks of the Forth, in presence of the two justiciaries of Scotland, and

others to whom the matter had been referred by command of David the

Second, by which Sir John Drummond resigned certain lands in the Lennox,

and shortly after, the residence of the family seems to have been

transferred from Drymen in Stirlingshire, where they had chiefly lived for

about two hundred years, to Stobhall, in Perthshire, which had come years

before come into their possession by marriage.

Sir Malcolm

Drummond, the eldest son, had four hundred francs for his share of the

forth thousand sent from France, to be distributed among the principal men

in Scotland in 1385, being designed in the acquittance “Matorme de Drommod.”

He was at the battle of Otterbourne in 1388, when his brother-in-law,

James, second earl of Douglas and Mar, was killed, on which event he

succeeded to the earldom of Mar in right of his wife, Lady Isabel Douglas,

only daughter of William, first earl of Douglas. Wyntoun calls him –

“Schyre Malcolm of Drummond, lord of Mar,

A manfull knycht, baith wise and war.”

That is, wary. From

King Robert the Third he received a charter, in which the king styles him

his “beloved brother,” of a pension of £20 furth of Inverness, in

satisfaction of the third part of the ransom (which exceeded six hundred

pounds) of Sir Randolph Percy, brother of Hotspur, who appears to have

been made prisoner by his assistance at the above-named battle. His death

was a violent one, having been seized by a band of ruffians and imprisoned

till he died “of his hard captivity.” This happened before 27th

May, 1403, as one that date his countess granted a charter in her

widowhood. Subsequent transactions may help to explain the causes of his

fate, as well as create suspicion as to the actual perpetrators. Not long

after his death, Alexander Stewart, a natural son of “the Wolf of Badenoch,”

a bandit and robber by profession, having cast his eyes on the lands of

the earldom, stormed the countess’ castle of Kildrummie, and either by

violence or persuasion obtained her in marriage. Fearing, however, that

for this bold act he might be called in question, he, on 19th

September 1404, presented himself at the castle gate, and surrendered the

castle and all within it to the countess, delivering at the same time the

keys into her hands, whereupon she, of her own free will, openly and

publicly chose him for her husband, when he assumed the title of earl of

Mar, and took possession accordingly. [See MAR, earl of.]

As Sir Malcolm

Drummond had died without issue, his brother, John, succeeded him. He held

the office of justiciary of Scotland, and had a safe-conduct into England

to meet his nephew King James the First at Durham, 13th

December 1423. He died in 1428. By his wife, Elizabeth Sinclair, daughter

of Henry, earl of Orkney, he had several sons, the youngest of whom, John,

left Scotland about 1418, and settling in the island of Madiera, prospered

there. He was known by the name of John Escortio, supposed to be a

corruption of Escossio, the Portuguese word for a Scotsman. Several

letters that afterwards passed betwixt his descendants and the Drummond

family in Scotland are inserted in Viscount Strathallan’s Genealogy of the

House of Drummond, 1681. One of these descendants, Manual Alphonso

Ferriara Drummond, during the minority of James the Fifth, sent from

Portugal a message by a gentleman named Thomas Drummond, then on his

travels, requesting an account of the family from which he was descended,

“with a testificate of their gentility and the coat of arms pertaining to

the name,” and stating that the number of descendants of John Escortio in

the Portuguese dominions was no less than two hundred. In reply to this

request, David Lord Drummond, who was then a minor, obtained from the

council of Scotland “a noble testimony under the great seal of the

kingdome, wherein the descent of the Drummonds from that first Hungarian

admiral to Queen Margaret is largely attested,” – the attesters being,

with the Archbishop of St. Andrews and the bishops of Aberdeen and

Dunblane, a number of th principal peers, knights, and barons of Scotland.

A short time after, namely, in 1533, the same Davie Lord Drummond signed a

bond, wherein he acknowledged relationship with the Campbells, who

consider the Drummonds merely a branch or offshoot from their tribe, being

descended, they say, from one Duncan Drummach, a brother of Ewen Campbell,

first knight of Lochawe. The connexion could only have been by marriage,

and does not seem to have been otherwise recognised by the head of the

Campbell clan, as the earl of Argyle of the time was among the attesters

of the above “noble testimony.”

John’s eldest

son, Sir Walter Drummond, was knighted by King James the Second, and died

in 1455. He had three sons: Sir Malcolm, his successor; John, deal of

Dunblane; and Walter of Ledcrieff, ancestor of the Drummonds of

Blair-Drummond, (now the Home Drummonds, Henry Home, the celebrated Lord

Kames, having married Agatha, daughter of James Drummond of

Blair-Drummond, and successor in the estate to her nephew in 1766); of

Gairdrum; of Newton, and other families of the name. We have already (see

art. BLAIR) referred to a feud between the Drummonds and the Blairs,

which led to George Drummond, (who had purchased the estate of Blair),

with his son, William, being set upon by more than twenty persons, and

slain in cold blood, as they were leaving the kirk of Blair in Perthshire,

on Sunday, 3d June 1554. In this outrage no less than eight persons of the

name of Blair, including the laird of Ardblair, were engaged. One son,

George Drummond, luckily survived to continue the family of

Blair-Drummond.

The eldest son

of the main trunk, that is, the Cargill and Stobhall family, Sir Malcolm

by name, had great possessions in the counties of Dumbarton, Perth, and

Stirling, and died in 1470. By his wife Marion, daughter of Murray of

Tullibardine, he had six sons. His eldest son, Sir John, was first Lord

Drummond; Walter, the second son, designed of Deanston, after being rector

of St. Andrews, became chancellor of Dunkeld, and afterwards dean of

Dunblane, and at last was appointed by James the Fourth clerk register of

Scotland. James, the third son, and Thomas, the fourth, were the ancestors

of several of the landed families of Scotland of the name of Drummond.

Sir John, the

eldest son, was a personage of considerable importance in the reigns of

James the Third and Fourth, having been concerned in most of the public

transactions of that period. He sat in parliament 6th May 1471,

under the designation fo dominus de Stobhall. IN 1483, he was one of the

ambassadors to treat with the English, to whom a safe conduct was granted

29th November of that year; again on 6th August

following, to treat of the marriage of James, prince of Scotland, and Anne

de la Pole, niece of Richard the Third. He was a commissioner for settling

border differences, nominated by the treaty of Nottingham, 22d September

1484, and on the 29th of the subsequent November, he had

another safe-conduct into England; subsequently he had three others. He

was created a peer y the title of Lord Drummond, 29th January

1487-8. Soon after he joined the party against King James the Third, and

sat in the first parliament of King James the Fourth, 6th

October 1488. In the following year he suppressed the insurrection of the

earl of Lennox, whom he surprised and defeated at Tillymoss. He was a

privy-councillor to James the Fourth, justiciary of Scotland, and

constable of the castle of Stirling. Although he wrote a paper of ‘Counsel

and Advice,’ for the benefit of those who should come after him, in which

occurs one wise maxim, namely, “In all our doings discretion is to be

observed, otherwise nothing can be done aright,” yet, upon one memorable

occasion he seems to have forgot this prudent rule, as well as the family

motto “gang warily,” as on 16th July 1515, he was committed a

close prisoner to Blackness castle, by order of the regent duke of Albany,

for having struck the lion herald on the breast, when he brought a message

to the queen-dowager from the lords of Albany’s party. The queen, on his

behalf, stated that the herald had behaved with insolence, and he was

released from prison, 22d November 1516. He died in 1519. His name

frequently occurs in the great seal register.

By his wife,

Lady Elizabeth Lindsay, daughter of David, duke of Montrose, the first

Lord Drummond, had three sons, and six daughters, the eldest of whom,

Margaret, was mistress to James the Fourth. Malcolm, the eldest son,

predeceased his father. William, the second son, styled master of

Drummond, suffered on the scaffold. In the year 1490, having been informed

that a party of the Murrays, with whom the Drummonds were at feud, were

levying teinds (for George Murray, abbot of Inchaffray) on his lands in

the parish of Monyvaird, along with Duncan Campbell of Dunstaffnage, and a

large body of followers, he hastened to oppose them. The Murrays took

refuge in the church of Monyvaird, and the master and his party were

retreating, when a shot from the church killed one of the Dunstaffnage

men, on which the Highlanders returned and set fire to the building. Being

roofed with heather, it was soon consumed, and according to the complaint

of the abbot, nineteen of the Murrays were burnt to death. James the

Fourth punished the ringleaders with death. The master of Drummond being

apprehended and sent prisoner to Stirling, was tried, convicted, and

speedily executed. His mother vainly begged his life on her knees, and his

sister, Margaret, the mistress of the king, also in vain pleaded in his

behalf. Those were ruthless times. From 1488 to 1502, the royal

treasurer’s books contain entries of gifts of jewellery, dresses, and

money to “Mistress Margret Drummond,” who seems to have lived openly with

the king, and he was so much attached to her that he would not marry while

she lived. She was poisoned in 1502, along with her two youngest sisters,

Euphemia Lady Fleming, and Sybilia, who accidentally joined her at her

last fatal repast. One of the last entries regarding her in the

treasurer’s books records a payment to the priests of Edinburgh for a

“Saule-mess for Mergratt, £5" They were buried in a vault, covered with

three fair blue marble stones in the middle of the choir of the cathedral

of Dunblane, and James soon after married the princess Margaret of

England. Sir John, the third son of the first Lord Drummond, got from his

father the lands of Innerpeffry, and had two sons, John Drummond of

Innerpeffry, and Henry, ancestor of the Drummonds of Riccartoun. John, the

eldest son, married his cousin, Margaret Stewart, natural daughter of King

James the Fourth, widow of John Lord Gordon, eldest son of the third earl

of Huntly. This lady was legitimated by letters patent under the great

seal, 1st February 1558-9.

William, the

unfortunate master of Drummond, had two sons, Walter, and Andrew, ancestor

of the Drummonds of Belyclone. Walter died in 1518, before his

grandfather. By Lady Elizabeth Graham, daughter of the first earl of

Montrose, he had a son, David, second Lord Drummond, who was served heir

to his great-grandfather, John, first lord, 17th February 1520.

His name frequently occurs in the great seal register between the years

1537 and 1571. He joined the association in behalf of Queen Mary at

Hamilton 8th May 1568, and died in 1571. On coming of age he

had married Margaret Stewart, daughter of Alexander, bishop of Moray, son

of Alexander duke of Albany, and by her he had a daughter Sybilia, married

to Sir Gilbert Ogilvy of Ogilvy. By a second marriage to Lilias, daughter

of Lord Ruthven, he had two sons and five daughters.. Jean, the eldest,

married the fourth earl of Montrose, high chancellor; Anne, the second,

the seventh earl of Mar, high treasurer; Lilias, the third, the master of

Crawford; Catherine, the fourth, the earl of Tullibardine; and Mary, the

youngest, Sir James Stirling of Keir. By marriages into the best families

the Drummonds very much increased the power, influence, and possessions of

their house. Of his two sons, Patrick, the elder, was third Lord Drummond;

James, the younger, created, 31st January 1609, Lord Maderty,

was ancestor of the viscounts of Strathallan. [See STRATHALLAN, Viscount

of.]

Patrick, third

Lord Drummond, embraced the reformed religion, and spent some time in

France. He died before 1600. He was twice married, and by his first wife,

Elizabeth, daughter of David Lindsay of Edzell, eventually earl of

Crawford, he had two sons and five daughters. The eldest daughter,

Catharine, married the master of Rothes; the second, Lilias, became

countess of Dunfermline, and the third, Jane, countess of Roxburghe; the

fourth, Elizabeth, married the fifth lord Elphinstone, and the youngest,

Anne, Barclay of Towie. The third daughter, Lady Roxburghe, a lady of

great beauty, had the honour of being celebrated by the poet Daniel, and

she was held in so high estimation for her abilities and virtue as to be

selected by James the Sixth as the governess of his children. She died in

October 1643. Her funeral was appointed for a grand gathering of the

royalists to massacre the Covenanters, but they found their numbers too

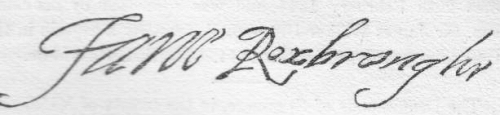

inconsiderable for the attempt. The following is her fac simile, taken frm

the Gentleman’s Magazine for February 1799, and said there to be the

signature of Jane, duchess (that is countess) of Roxburghe.

[signature of

Jane Roxburghe]

It is

appended to a receipt, dated 10th May 1617, for £500, part of

the sum of three thousand pounds, of his majesty’s free and princely gift

to her, in consideration of long and faithful service done to the queen,

as one of the ladies of the bedchamber to her majesty.

The elder son, James, fourth Lord Drummond, passed a considerable portion

of his youth in France, and after James the Sixth’s accession to the

English throne, he attended the earl of Nottingham on the embassy to the

Spanish court. On his return he was created earl of Perth, 4th

March 1605. John, the younger son, succeeded his brother in 1611, as

second earl of Perth. [See PERTH, earl of.]

The Hon. John Drummond, second son of James, third earl of Perth, was

created in 1685 viscount, and in 1686 earl of Melfort; [See MELFORT, earl

of] and his representative Captain George Drummond, duc de Melfort, and

Count de Lussan in France, whose claim to the earldom of Perth in the

Scottish peerage was established by the House of Lords, June, 1853, is the

chief of the clan Drummond, which, more than any other, signalized itself

by its fidelity to the lost cause of the Stuarts.

_____

The family of Drummond of Hawthornden, in Mid Lothian, are cadets of the

Perth Drummonds. In the latter part of the fourteenth century, William

Drummond, a younger son of the family, and brother to Annabella, the queen

of Robert the Third, married Elizabeth, daughter and one of the

co-heiresses of William Airth of Airth, and with her acquired the barony

of Carnock in Stirlingshire. The Carnock estate was sold by Sir John

Drummond, the last of the elder branch of that line, to Sir Thomas

Nicholson. Sir John fell in the battle of Alford in 1645, fighting under

the celebrated marquis of Montrose. The barony of Hawthornden was

purchased by John, afterwards Sir John Drummond, second son of Sir Robert

Drummond of Carnock, and he became the founder of the Hawthornden family.

In the year 1388 Hawthornden belonged to the Abernethys, by whom it was

sold to the family of Douglas, and by them disponed to Drummond of Carnock.

The families of Abernethy and Drummond became united by the marriage of

Bishop Abernethy and Barbara Drummond, only daughter and heiress of

William Drummond, Esq. of Hawthornden.

Of

William Drummond, the celebrated poet, the most remarkable of the family

of Hawthornden, a memoir is given below.

The estate afterwards came into possession of John Forbes, Esq., commander

R.N., nephew of the said Bishop Abernethy-Drummond. He married Mary,

daughter of Dr. Ogilvie, M.D. of Murtle, a lineal descendant of Sir John

Drummond, the first of Hawthornden, and heiress by special settlement of

her cousin, the above-named Mrs. Barbara Drummond, who died in 1789, upon

which Mr. Forbes assumed the additional surname and arms of Drummond. His

only surviving daughter, Margaret Anne Forbes Drummond, married in 1810,

Francis Walker, writer to the signet, eldest son of James Walker, Esq. of

Dalry, in Mid Lothian, and he also assumed the surname and arms of

Drummond. Mr. Forbes Drummond was created a baronet 27th

February 1828, with remainder to his son-in-law, and died 28th

May 1829. Sir Francis Walker Drummond, second baronet, born in 1781, died

29th February 1844, and was succeeded by his eldest son, Sir

James Walker Drummond, formerly a captain in the Grenadier guards, retired

in 1844. Married, with issue.

_____

The Drummonds of Stanmore, in the county of Middlesex, are descended from

Andrew Drummond, brother of the fourth viscount of Strathallan, and

founder of the well-known banking house of Drummond and Co. of London, who

purchased the estate of Stanmore in 1729. His great-grandson, George

Harley Drummond of Stanmore, born 23d November 1783, married Margaret,

daughter of Alexander Munro, Esq. of Glasgow, with issue, is M.P. for

Surrey. (1853.)

The Drummonds of Cadlands, Hampshire, are a branch of the same family.

_____

The Drummonds of Concraig descended from the above-mentioned Sir Maurice

Drummond, (who married the heiress of Concraig,) second son of Sir Malcolm

Drummond, tenth seneschal of Lennox, and are now represented by Drummond

of the Boyce, Gloucestershire, a modern cadet of the Drummonds of Megginch

castle, Perthshire. Allusion has already been made to the feud between the

Drummonds and the Murrays, to which the unfortunate master of Drummond,

eldest surviving son of the first Lord Drummond, fell a victim on the

scaffold. It originated in the following circumstance: In the year 1391,

Sir Alexander Moray of Ogilface (or Ogilvie) and Abercairney had

accidentally killed a gentleman named William Spalding, for which he was

summoned to take his trial before Sir John Drummond, third knight of

Concraig, justiciary-coroner and seneschal or steward of Strathearn, in a

justice court held at Foulis in Perthshire; and on pleading the privilege

of being of the kin of Macduff earl of Fife (see MACDUFF,) the matter was

referred to Lord Brechin, the lord-justice-general. That functionary

decreed that the law of clan Macduff should not protect Sir Alexander from

the jurisdiction of his ordinary justice. From that jurisdiction Alexander

and his friends and successors, used every effort to be freed, but the

family of Concraig as zealously endeavoured to hold them to it, until,

upon a new occasion, in the reign of James the Third, a liberation was

granted to some of the Murrays, and secured to their posterity. In the

meantime, Patrick Graham, having, through marriage with the heiress,

become earl of Strathearn, Sir Alexander Moray and his friends prevailed

upon him to deprive Sir John Drummond, although he was his brother-in-law,

of his office, and at the head of a large retinue, he proceeded from

Methven, his place of residence, with the determination of dispersing Sir

John’s court then sitting at the Skeall of Crieff. On receiving notice of

his approach, Sir John hastened with his attendants to meet him, and the

earl was killed at the first encounter. Sir John immediately fled to

Ireland, where it is said he died. The feuds that arose out of this

unlucky event forced the Drummonds of Concraig to maintain so many

followers, that they were obliged from the expense to part with many of

their lands. The barony of Concraig was purchased from them by Sir John

Drummond of Cargill and Stobhall, and the dignities of seneschal or

steward of Strathearn, justiciary-coroner of the whole district, and

ranger of the forest, (which heritable offices had been conferred on the

Concraig Drummonds by King David the Second,) were conveyed by Maurice

Keir-Drummond, sixth baron of Concraig (who had married a daughter of Sir

Andrew Moray of Ogilvie and Abercairney) to the first Lord Drummond.

John Drummond, second son of Sir John Drummond, third knight of Concraig,

was ancestor of the Drummonds of Lennoch, in Strathearn, whose

representative in 1640, John Drummond, eighth baron of Lennoch, purchased

from Sir John Hay, ancestor of the earl of Kinnoul, the barony of Megginch

in Perthshire. Admiral Sir Adam Drummond of Megginch castle, K.C.H., the

thirteenth of Lennoch and sixth of Megginch castle, died in 1849. Born in

1770, he married in 1801, Lady Charlotte Murray, eldest daughter of John,

baronet, and had issue. His eldest son succeeded him. His brother, Sir

Gordon Drummond, C.C.B. (Created in 1817), a general in the army (1825),

died in 1854.

DRUMMOND, WILLIAM,

of Hawthornden, an elegant and ingenious poet, the son of Sir John

Drummond of Hawthornden, gentleman usher to King James the Sixth, was born

there, December 13, 1585. He was educated at the university of Edinburgh,

after which he spend four years at Bourges in France, studying the civil

law, being intended by his father for the bar. On his father’s death he

returned to Scotland in 1610, and retiring to his romantic seat of

Hawthornden, in the parish of Lasswade, Mid Lothian, and in the immediate

neighbourhood of Roslin castle, devoted himself to the perusal of the

ancient classics and the cultivation of poetry. A dangerous illness

fostered a melancholy and devout turn of mind, and his first productions

were ‘The Cypress Grove,’ in prose, containing reflections upon death, and

‘Flowers of Zion, or Spiritual Poems,’ published at Edinburgh in 1616. The

death of a young lady, a daughter of Cunninghame of Barnes, to whom he was

about to be married, overwhelmed him with grief, and to divert his

thoughts from brooding on his loss, he again proceeded to the continent,

where he remained for eight years, residing chiefly at Paris and Rome.

During his travels he made a collection of the best ancient and modern

books, which, on his return, he presented to the college of Edinburgh. The

political and religious dissensions of the times induced him to retire to

the seat of his brother-in-law, Sir John Scot of Scotstarvet, in Fife,

during his stay with whom he wrote his ‘History of the Five Jameses, Kings

of Scotland,’ a highly monarchical work, which was not published till

after his death. In his 45th year he married Elizabeth Logan,

who bore so strong a resemblance to the former object of his love that she

at once gained his affections. She was the grand-daughter of Sir Robert

Logan of Restalrig, and by her he had several children. He died December

4, 1649, in his 64th year, his death being said to have been

hastened by grief for the untimely fate of Charles the First. Among his

intimate friends and correspondents were, the earl of Stirling, Michael

Drayton, and Ben Jonson, the latter of whom walked all the way to

Hawthornden to pay him a visit, in the winter of 1618-19. Drummond has

been much blamed for having kept notes of the cursory opinions thrown out

in conversation with him by his guest, and for having chronicled some of

his personal failings, but besides being merely private memoranda, never

intended for publication, and never published by himself, a consideration

which ought to acquit him of anything mean or unworthy in the matter,

these notes are valuable as preserving characteristic traits of Ben Jonson,

which have partly been confirmed from other sources. Modern literature is

absolutely flooded with the ‘reminiscences,’ ‘diaries,’ ‘journals,’

‘correspondence,’ & c., of great and little poets, orators, and statesmen,

and no one now thinks of reprehending a system which threatens to put an

end to all friendly confidence and to all social and familiar intercourse

in literary society. Besides his History he wrote several political

tracts, all strongly in favour of royalty. It is principally as a poet,

however, that Drummond is now remembered. His poems, though occasionally

tinged with the conceits of the Italian school, possess a harmony and

sweetness unequalled by those of any poet of his time; his sonnets are

particularly distinguished for tenderness and delicacy. His works are:

Poems by that most famous wit, William Drummond of Hawthornden. London,

1656, 8vo.

Cypress Grove, Flowers of Zion, or Spiritual Poems. Edin. 1623, 1630, 4to.

The History of Scotland from the year 1423 until the year 1542: and

several memorials of State during the reigns of James VI. and Charles I.;

with an introduction by Mr. Hall. London, 1655, fol. Reprinted with cuts.

Lond. 1681, 8vo. Both editions very inaccurate as to names and dates.

Memorials of State, Familiar Epistles, Cypress Grove, &c. London, 1681,

8vo.

Polemo Middinia, or the Battle of the Dunghill, (a rare example of

burlesque, and the first macaronic poem by a native of Great Britain,)

published with Latin notes, by Bishop Gibson. Oxf. 1691, 4to. By Messrs.

Foulis of Glasgow. 1768. This piece has been republished, with some other

Tracts on the same subject, entit. Carminum Rariorum Macaronicorum

Delectus. In usum Ludorum Apollinarum. Edinburgi, 1801, 8vo.

The subjoined woodcut of Drummond of Hawthornden is from a portrait in

Pinkerton’s Scottish Gallery:

[William

Drummond of Hawthornden]

DRUMMOND, GEORGE,

a benevolent and public-spirited citizen of Edinburgh, the son of George

Drummond of Newton, was descended from the old and knightly house of

Stobhall, through a younger son of the cadet branch of Newton of Blair,

and was born June 27, 1687. He received his education at Edinburgh, and

was early distinguished for his proficiency in the science of calculation.

When only eighteen years of age he was employed by the committee of the

Scots parliament to give his assistance in arranging the national accounts

previous to the Union; and, in 1707, on the establishment of the excise,

he was appointed accountant-general. In 1715, when the earl of Mar raised

the standard of rebellion, he was the first to give notice to government

of that nobleman’s proceedings, being one of the very few gentlemen of his

Jacobite clan who appeared in arms for the reigning dynasty. Collecting a

company of volunteers, he joined the royal forces, and fought at

Sheriffmuir. The earliest notice of Argyle’s victory was despatched by him

to the magistrates of Edinburgh, in a letter written on horseback on the

field of battle. In the same year he was promoted to a seat at the board

of excise, and, in April 1717, was appointed one of the commissioners of

the board of customs. In 1725 he was elected lord provost of Edinburgh, an

office which he filled six times with uniform popularity and credit. In

1727 he was named one of the commissioners and trustees for improving the

fisheries and manufactures of Scotland, and, in October 1737, was created

one of the commissioners of excise; an office which he held till his

death. To his public spirit and patriotic zeal the city of Edinburgh is

indebted for many of its improvements. He was the principal agent in the

erection of the Royal Infirmary, and, by his exertions, a charter was

procured in August 1736, the foundation-stone being laid August, 2, 1738.

In 1745, upon the approach of the rebels, Mr. Drummond again joined the

army, and was present at the battle of Prestonpans. In September 1753, as

Grand Master of the Freemasons in Scotland, he laid the foundation of the

Royal Exchange . In 1755 he was appointed one of the trustees of the

forfeited estates, and elected a manager of the Select Society for the

encouragement of Arts and Sciences in Scotland. In October 1763, during

his sixth provostship, he laid the foundation-stone of the North Bridge,

which connects the New Town of Edinburgh with the Old. He died November 4,

1766, in the 80th year of his age, while filling the office of

lord provost, and was buried in the Canongate churchyard, being honoured

with a public funeral. To Provost Drummond Dr. Robertson, the historian,

owed his appointment as principal of the university of Edinburgh, which

was also indebted to him for the institution of five new professorships. A

few years after his death, a bust of him, by Nollekens, was erected in

their public hall by the managers of the Royal Infirmary, bearing the

following inscription from the pen of Principal Robertson: “George

Drummond, to whom this country is indebted for all the benefit which it

derives frm the Royal Infirmary.” Drummond Street, the street at the back

of the Infirmary, takes its name from him, as does also Drummond Place, in

the new town, his villa of Drummond Lodge having stood almost in the

centre of that modern square. His brother, Alexander, who was some time

British consul at Aleppo, was the author of ‘Travels through different

Cities of Germany, Italy, Greece, and several parts of Asia, as far as the

banks of the Euphrates.’ London, 1754. The provost’s daughter was married

to the Rev. John Jardine, D.D., one of the ministers of the Tron Church,

Edinburgh, and was the mother of Sir Henry Jardine, at one period king’s

remembrancer in Exchequer for Scotland, who died 11th August

1851.

DRUMMOND, ROBERT HAY,

a distinguished prelate of the Church of England, the second son of George

Henry, seventh earl of Kinnoul, by Lady Abigail Harley, second daughter of

Robert, earl of Oxford, lord high treasurer of England, was born in London

November 10. 1711. After being educated at Westminster school, he was

admitted a student of Christ church, Oxford, and having taken his degree,

he accompanied his cousin, the duke of Leeds, on a tour to the continent.

In 1735 he returned to college, and soon after entered into holy orders,

when he was presented by the Oxford family to the rectory of Bothall in

Northumberland. In 1737, on the recommendation of Queen Caroline, he was

appointed chaplain in ordinary to the king, George the Second. In 1739, he

assumed the name of Drummond, as heir of entail of his great-grandfather,

William, first viscount of Strathallan, by whom the estates of Cromlix and

Innerpeffrey were settled on the second branch of the Kinnoul family. In

1743 he attended the king when his majesty joined the army on the

continent, and on 7th July of that year, he preached the

thanksgiving sermon before him at Hanover after the victory at Dettingen.

On his return to England, he was installed prebendary of Westminster, and

in 1745, was admitted B.D. and D.D. In 1748 he was consecrated bishop of

St. Asaph. In 1753, in an examination before the privy council, he made so

eloquent a defence of the political conduct of his friends, Mr. Stone and

Mr. Murray, (afterwards Lord Chief Justice Mansfield) that the king, on

reading the examination, is said to have exclaimed, “That is indeed a man

to make a friend of!” In May 1761, he was translated to the see of

Salisbury, and in the same year he preached the coronation sermon of

George the Third. In the following November he was enthroned Archbishop of

York, and soon after was sworn a privy councillor and appointed high

almoner. He died at his palace of Bishopthorpe December 10, 1776, in the

66th year of his age, leaving the character of an amiable man

and highly estimable prelate. He had married on 31st January

1748, the daughter and heiress of Peter Auriol, merchant in London, by

whom he had a daughter, Abigail, who died young, and is commemorated in

one of the epitaphs of Mason the poet, and six sons, the eldest of whom,

Robert Auriol, became ninth earl of Kinnoul. The youngest, the Rev. George

William Hay Drummond, prebendary of York, and author of a volume of poems

entitled ‘Verses Social and Domestic,’ (Edin. 1802) was editor of his

father’s sermons, six in number, which, with a letter on Theological

Study, appeared in one volume 8vo in 1803, with a life prefixed. He was

unfortunately drowned off Bideford, while proceeding from Devonshire to

Scotland, in 1807.

DRUMMOND, WILLIAM ABERNETHY, D.D.,

bishop of Edinburgh was descended from the family of Abernethy of Saltoun,

in Banffshire, and on his marriage with the heiress of Hawthornden, in the

county of Edinburgh, he assumed the name of Drummond in addition to his

own. He at first studied medicine, but was subsequently, for many years,

minister of an episcopalian church in Edinburgh. Having paid his respects

to Prince Charles Edward, when he held his court at Holyroodhouse, he was

afterwards exposed to much annoyance and danger on that account, and was

even glad to avail himself of his medical degree, and wear for some years

the usual professional costume of the Edinburgh physicians of that period.

He was consecrated bishop of Brechin at Peterhead, September 26, 1787, and

a few months afterwards, was elected to the see of Edinburgh, in which

charge he continued till 1805, when, on the union of the two classes of

Episcopalians, he resigned in favour of Dr. Sandford. He retained,

however, his pastoral connection with the clergy in the diocese of Glasgow

till hi death, which took place August 27, 1809. Keith says his

intemperate manner defeated in most cases the benevolence of his

intentions, and only irritated those whom he had wished to convince. [Scottish

Bishops, App. p. 545.] He wrote several small tracts, and was a good

deal engaged in theological controversy both with Protestants and Roman

Catholics.

DRUMMOND, SIR WILLIAM,

an eminent scholar and antiquary, belonged to a family settled at Logie-Almond

in Perthshire, where he possessed an estate. The date of his birth is not

known, nor the circumstances of his early life. At the close of 1795, he

was returned to parliament on a vacancy in the representation of the

borough of St. Mawes, Cornwall, and in the two following parliaments,

which met in 1796 and 1801, he sat for Lostwithiel. At the time of his

second election he had been appointed envoy extraordinary and minister

plenipotentiary at the court of Naples, and soon after he was sent to

Constantinople as ambassador to the Sultan. In 1801 he was invested with

the Turkish order of the Crescent, which was confirmed by royal license

inserted in the London Gazette September 8, 1803. In 1808, while residing

as envoy at the court of Palermo, he embarked in a scheme with the duke of

Orleans (subsequently king of the French) to secure the regency of Spain

to Prince Leopold of Sicily, a project which failed at the very outset,

and for his share in which he has been severely censured in Napier’s

History of the Peninsular War [vol. i. p. 177.] In his latter years, for

the benefit of his health, which required a warmer climate than that of

England, he resided almost constantly on the continent, chiefly at Naples,

and he died at Rome March 29, 1828. He was a member of the privy council,

and a fellow of the royal societies of London and Edinburgh. Of modest,

retiring, and unobtrusive manners, he was a close and assiduous student,

and published various works, principally in the department of antiquities,

an account of which, with a memoir, is given in the Encyclopedia

Britannica, seventh edition; but his reputation as a scholar and antiquary

will chiefly rest on his ‘Origin of several Empires, States, and Cities,’

mentioned afterwards. The following is a list of his writings:

A

Review of the Government of Sparta and Athens. London, 1794, large 8vo.

The Satires of Perseus, translated. London, 1798. This work appeared about

the same time as Mr. Gifford’s version of the same poet, and in freedom

and fidelity was thought to be equal to it.

Academical questions. London, 1805, 4to. A metaphysical work; to which he

intended a subsequent volume to complete its design, but it never

appeared.

Herculanensia, or Archaeological and Philological Dissertations concerning

a Manuscript found among the Ruins of Herculaneum. London, 1810, 4to.

Published in conjunction with Robert Walpole, Esq.

An

Essay on a Punic Inscription found in the Island of Malta. London, 1811,

royal 4to.

Odin, a Poem. Part i. London, 1818, 4to. The object of this unfinished

poem, which soon fell into oblivion, was to embody in verse some of the

more striking features of the Scandinavian mythology.

Origines, or Remarks on the Origin of several Empires, States, and Cities.

London, 3 vols. 8vo. The first volume, embracing the origin of the

Babylonian, the Assyrian, and the Iranian Empires, appeared in 1824; the

second, which is wholly devoted to the subject of Egypt, including the

modern discoveries in hieroglyphics, came out in 1825; and the third,

which treats of the Phoenicians and Arabia, was published in 1826.

In

1811, he had printed for private circulation, but not published, a sort of

philological treatise entitled ‘Ædipus Judaicus,’ designed to show that

some of the narratives in the Old Testament are merely allegorical, and a

copy of it having fallen into the hands of the Rev. Dr. George Doyley,

that gentleman published an answer under the title of “Letters to the

Right Hon. Sir William Drummond, in defence of particular passages of the

Old Testament, against his late work entitled ‘Ædipus Judaicus.’ The work

was also attacked in the Edinburgh Review.

He

was also an occasional contributor to the Classical Journal, in which his

papers on subjects of antiquity, particularly the zodiac of Denderah,

attracted the general admiration of the learned of his time.

DRUMMOND, THOMAS,

the inventor of the brilliant “light” that bears his name, was born in

Edinburgh in October 1797. He was the second of three sons, and after his

father’s death, which happened whilst he was yet an infant, his mother

removed to Musselburgh, where she resided for many years. He received his

education At the High School of his native city, and at this time formed

an acquaintance with Professors Playfair, Leslie, and Brewster, and also

with Professors Wallace and Jardine, whose pupil he more especially was.

In February 1813, he was appointed to a cadetship at Woolwich, where he

soon became distinguished for his mathematical abilities. So rapid was his

progress that at Christmas of the same year he entered the second academy,

having commenced at the sixth. His friend and master at Woolwich,

Professor Barlow, thus sketched his mathematical character at this period:

“Mr. Drummond, by his amiable disposition, soon gained the esteem of the

masters under whom he was instructed; with the mathematical masters in

particular his reputation stood very high, not so much for the rapidity of

his conception as for his steady perseverance, and for the original and

independent views he took of the different subjects that were placed

before him. there were among his fellow-students some who comprehended an

investigation quicker than Drummond, but there was no one who ultimately

understood all the bearings of it so well. While a cadet in a junior

academy, not being satisfied with a rather difficult demonstration in the

conic sections, he supplied one himself on an entirely original principle,

which at the time was published in Leybourne’s ‘Mathematical Repository,’

and was subsequently taken to replace that given in Dr. Hutton’s ‘Course

of Mathematics,’ to which he had objected. This apparently trifling event

gave an increased stimulus to his exertions, and may perhaps be considered

the foundation-stone of his future scientific fame. After leaving the

academy he still continued his intercourse with his mathematical masters,

with whom he formed a friendship which only terminated in his much

lamented death.”

During his preliminary and practical instruction in the special duties of

the engineer department, his talent for mechanical combination became

conspicuous, and he also largely devoted his attention to the acquisition

of military knowledge, Jomini and Bousmard being his favourite authors.

After serving for a short time at Plymouth, he went to Chatham, and during

this period he obtained leave of absence for the purpose of visiting the

army of occupation in France, and attending one of the great reviews.

After his Chatham course was completed he was stationed at Edinburgh,

where his duties were of an ordinary character, relating merely to the

charge and repair of public works, but he eagerly availed himself of the

opportunity afforded him of pursuing the higher mathematical studies at

the college and classes, and among the scientific society for which his

native city was at that period distinguished. His prospects of promotion

at this time were, however, so disheartening that he seriously meditated

leaving the army for the English bar, and with this view had actually

entered his name at Lincoln’s Inn.

In

the autumn of 1819 he fortunately became acquainted with Colonel Colby,

when that officer was passing through Edinburgh, on his return from the

trigonometrical operations in the Scottish Highlands, and in the course of

the following year, an offer from him to take part in the trigonometrical

survey was gladly accepted. He had now the advantage of a residence during

each winter in London, and besides devoting himself more closely to the

study of the higher branches of mathematics, he began the study of

chemistry, in which he was destined to achieve his greatest and most

enduring triumph. He attended the lectures of Professors Brande and

Faraday, and soon made his new knowledge available to the duties on which

he was employed. The writer of a memoir of Captain Drummond in the Penny

Cyclopedia (supplement), to which this sketch of him is largely indebted,

thus describes the useful and important invention known by the name of

“Drummond’s light.” “The incandescence of lime,” he says, “having been

spoken of in one of the lectures, the idea struck him that it could be

employed to advantage as a substitute for argand lamps in the reflectors

used on the survey for rendering visible distant stations; because, in

addition to greater intensity, it afforded the advantage of concentrating

the light as nearly as possible into the focal point of the parabolic

mirror; by which the whole light would be available for reflecting in a

pencil of parallel rays, whereas of the argand lamp only the small portion

of rays near the focus was so reflected. On this subject his first

chemical experiments were formed. On the way from the lecture he purchased

a blowpipe, charcoal, &c., and that very evening set to work. At this

period (1824), a committee of the House of Commons recommended that the

survey of Ireland should be begun, and that Colonel Colby should make

arrangements for carrying it on. For this survey instruments of improved

construction were required. Among others, a means of rendering visible

distant stations was desirable. The recent experience of the Western

Islands had shown the probability that in a climate so misty as Ireland

the difficulty of distant observations would be greatly increased, and

Colonel Colby at once saw the important results which might follow such an

improvement of the lamp as that which Drummond had devised. Under his

judicious advice the experiments were prosecuted, and were rapidly

attended with success. Their progress and results are detailed by the

author in the ‘Philosophical Transactions’ for 1826, as well as the first

application of the lamp to actual use in Ireland. When a station. Slieve

Snaught in Donegal, had long in vain been looked for from Davis mountain,

near Belfast, the distance being sixty-six miles, and passing across the

haze of Lough Neagh, Mr. Drummond took the lamp and a small party to

Slieve Snaught, and by calculation succeeded so well in directing the axis

of the reflector to the instrument that the light was seen, and its first

appearance will long be remembered by those who witnessed it. The night

was dark and cloudless, the mountain and the camp were covered with snow,

and a cold wind made the duty of observing no enviable task. The light was

to be exhibited at a given hour, and to guide the observer, one of the

lamps formerly used, an argand in a lighthouse reflector, was placed on

the tower of Randalstown church, which happened to be nearly in the line

at fifteen miles. The time approached and passed, and the observer had

quitted the telescope, when the sentry cried, ‘The light!’ and the light

indeed burst into view, a steady blaze of surpassing splendour, which

completely effaced the much nearer guiding beacon.” Mr. Drummond’s

original heliostat was not completed till 1825. Various improvements were

afterwards made on it. He also directed his attention to the improvement

of the barometer, and made a syphon with his own hands, which performed

remarkably well. Indeed, at this period, so active was his mind and so

constant his application that, we are told, scarcely an instrument existed

that he did not examine and consider, with a view to render it useful for

the purposes of the survey.

Owing to a severe illness, brought on by his close application to his

duties, Mr. Drummond was compelled to leave Ireland, and return for a time

to Edinburgh. He had taken much pains to perfect his light, and with the

view of adapting it to lighthouses, the corporation of Trinity house

placed at his disposal a small lighthouse at Purfleet, and the experiments

he made, with their success, are detailed in the ‘Philosophical

Transactions’ for 1830. His attention, however, was soon directed away

from it, and it had never yet been applied to them. His name had been

recommended by Mr. Bellenden Ker, who was employed in the preparation of

the details of the Reform Bill, to Lord Brougham, then lord chancellor, as

a person eminently qualified to superintend the laborious operations

necessary to perfecting the schedules, and he was at once appointed to

this commission. These schedules were based upon the calculations made by

him relative to the boundaries of the old and new boroughs. He was at this

time but a lieutenant of the engineers, but his talents and scientific

attainments were well known.

After

the passing of the Reform Bill (in 1832) he returned to his duties on the

survey in Ireland, but was soon appointed private secretary to Lord

Althorp )afterwards earl Spencer), then chancellor of the exchequer. On

the dissolution of the Reform ministry, he obtained, through the influence

of Lord Brougham, a pension of three hundred pounds a-year.

In

1835 he was appointed under-secretary for Ireland. He was at the head of

the commission on Irish railways, and distinguished himself greatly in the

report on the same. One striking remark of his, that “property has its

duties as well as its rights,” has been often quoted. He died April 15,

1840, and soon after his death there was a subscription for a statue of

him, executed at Rome, to be placed at Dublin. Both Lord Spencer and Lord

John Russell have borne ample testimony to his attainments and estimable

qualities, the latter in the House of Commons.

REPORT ON THE MANUSCRIPTS OF CHARLES STIRLING-HOME-DRUMMOND

MORAY, ESQUIRE, OF BLAIRDRUMMOND, AT BLAIR-DRUMMOND, AND ARDOCH, BOTH IN

THE COUNTY OF PERTH, BY WILLIAM FRASER, LL.D., EDINBURGH.

Manuscripts |