FRASER,

sometimes written Frazer, a surname derived from the French word

fraizes or fraises, strawberries, seven strawberry flowers

forming part of the armorial bearings of families of this name. The

first of this surname in Scotland was of Norman origin, and came over

with William the Conqueror. The Chronicles of the Fraser family pretend

that their ancestor was one Pierre Fraser, seigneur de Troile, who in

the reign of Charlemagne, came to Scotland with the ambassadors from

France to form a league with King Achaius, and that his son, in the year

814, became thane of the Isle of Man, but all this is mere fable. Their

account of the creation of their arms is equally an invention. According

to their statement, in the reign of Charles the Simple of France, Julius

de Berry, a nobleman of Bourbon, entertaining that monarch with a dish

of fine strawberries, was, for the same, knighted, the strawberry

flowers, fraises, given him for his arms, and his name changed

from de Berry to Fraiseur or Frizelle. They claim affinity with the

family of the duke de la Frezeliere, in France. The first of the name in

Scotland is understood to have settled there in the reign of Malcolm

Canmore, when surnames first began to be used, and although the Frasers

afterwards became a powerful and numerous clan in Inverness-shire, their

earliest settlements were in East Lothian and Tweeddale.

In the reign

of David the First, Sir Simon Fraser possessed half of the territory of

Keith in East Lothian (from him called Keith Simon), and to the monks of

Kelso he granted the church of Keith. He had a daughter, Eda, married to

Hugh Lorens, and their daughter, also named Eda, became the wife of

Hervey, the king’s marechal, proprietor of the other half of the

territory of Keith, called after him Keith Hervey. He was the ancestor

of the north country Keiths, earls Marischal. A member of the same

family, Gilbert de Fraser, obtained the lands of North Hailes, also in

East Lothian, as a vassal of the earl of March and Dunbar, and is said

to be a witness to a charter of Cospatrick to the monks of Coldstream,

during the reign of Alexander the First. He also possessed large estates

in Tweeddale. His eldest son, Oliver de Fraser, who flourished between

1175 and 1199, built Oliver castle, in the shire of Peebles, celebrated

in history as the stronghold of the heroic companion of Wallace, Sir

Simon Fraser, of whom a memoir is given afterwards. Dying without issue,

Oliver was succeeded by his nephew, Adam de Fraser, He was the son of

Udard Fraser, Gilbert’s second son, who had settled in Peebles-shire.

His son, Laurence Fraser, is witness to a charter of the ward of East

Nisbet, by Patrick earl of Dunbar to the monks of Coldingham, in 1261.

Laurentius Fraser, dominus de Drumelzier, possessed the lands of

Mackerston in Roxburghshire. His son, also named Laurence, lived during

the wars of succession, and with his eldest daughter the estate of

Drumelzier went by marriage into the family of Tweedie. The second

daughter, maarying Dougal Macdougall, carried to him the estate of

Mackerston, in the reign of David the Second, and it now belongs to a

descendant of his on the female side.

In the reign

of Alexander the Second the chief of the family was Bernard de Fraser,

supposed to have been the grandson of the above-named Gilbert, by a

third son, whose name is conjectured to have been Simon. [Anderson’s

Hist. Acc. of the frasers, p. 8.] Bernard was a frequent witness to

the charters of Alexander the Second, and in 1234 was made sheriff of

Stirling, an h onour long hereditary in his family. By his talents he

raised himself from being the vassal of a subject to be a tenant in

chief to the king. He acquired the ancient territory of Oliver castle,

which he transmitted to his posterity. He was one of the magnates of

Scotland who swore to the performance of the treaty of peace agreed upon

between Alexander the Second and Henry the Third of England at York in

1237, and is said to have married Mary Ogilvie, daughter of Gilchrist,

thane of Angus, whose mother, Marjory, was the sister of Kings Malcolm

the Fourth and William the Lion, and the daughter of Prince Henry. He

was succeeded by his son Sir Gilbert Fraser, who was sheriff or

vicecomes of Traquair during the reigns of Alexander the Second and his

successor. He had three sons; Simon, his heir; Andrew, sheriff of

Stirling in 1291 and 1293; and William, chancellor of Scotland from 1274

to 1280, and bishop of St. Andrews from 1279 to his death in 1297. He

was first dean of Glasgow, and was consecrated bishop at Rome by Pope

Nicholas the Third in 1280. In 1283, according to Wintoun, (Chronicles,

p. 528,) he obtained for the bishops of St. Andrews, from Alexander

the Third, the privilege of coining money. After the death of that

monarch, he was one of the lords of the regency chosen by the states of

Scotland, during the minority of the infant queen Margaret, styled “the

maiden of Norway;” and as such was appointed to treat with the Norwegian

plenipotentiaries on her affairs. On the death of that princess in 1291,

he rendered a compelled homage to Edward the First of England, by whom

he was created one of the guardians of Scotland. He was one of the early

assertors of the independence of his country, and within a month after

the accession of John Baliol to the throne, bishop Fraser joined with

several others in a complaint against the English monarch for

withdrawing causes out of Scotland contrary to his engagement and

promises, and in prejudice of Baliol’s sovereign rights and authority.

It was at the command of this patriotic bishop that Sir William Wallace,

when guardian of the kingdom, put all the English who held them, out of

their church benefices in Scotland. In 1295 he was one of the

commissioners who concluded the fatal treaty with King Philip of France,

by which the latter agreed to give Baliol his niece, the eldest daughter

of Charles count of Anjou, in marriage to his son and heir, a treaty,

styled by Lord Hailes, “the groundwork of many more equally honourable

and ruinous to Scotland.” [Annals, vol. i. p. 234.] Bishop Fraser

died at Arteville in France, 13th September 1297. His body

was buried in the church of the friars predicants in Paris, but his

heart, enclosed in a rich box, was brought to Scotland by his successor,

Bishop Lamberton, and entombed in the wall of the cathedral of St.

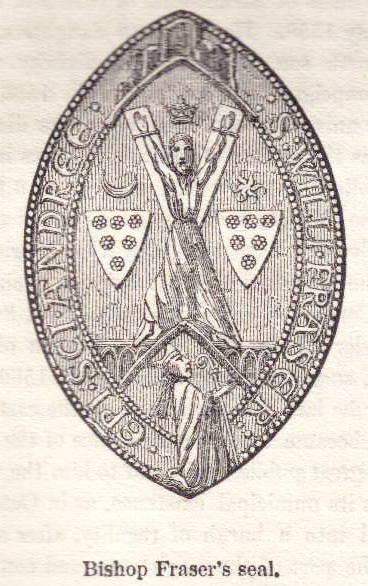

Andrews. Following is a representation of his seal from Anderson’s

Diplomata Scotiae, plate 100, the smallest one there.

[Bishop Fraser’s seal]

Sir Simon Fraser, the eldest son, was a man of great influence and

power. He possessed the lands of Oliver castle, Niedpath castle, and

other lands in Tweeddale; and accompanied King Alexander the Second in a

pilgrimage to Iona, a short time previous to the death of that monarch.

He was knighted by Alexander the Third, who, in the beginning of his

reign, conferred on him the office of high sheriff of Tweeddale, which

he held from 1263 to 1266. He was one of the magnates Scotiae

who, in 1285, engaged to support Margaret of Norway as the successor of

Alexander the Third. He sat in the famous parliament of Brigham in 1290,

when the marriage of Margaret with Prince Edward of England was

proposed. He supported the title of Baliol to the throne till basely

surrendered by himself, and in conjunction with his brothers, William

and Sir Andrew, and his cousin Sir Richard Fraser, was appointed an

arbiter by Baliol for determining the right of the several competitors

to the crown, 5th June 1291. He swore fealty to Edward the

First at Norham on the 12th of the same month, and again on

23d July at the monastery of Lindores. He died the same year. He had an

only son, Sir Simon Fraser, the renowned patriot, of whom a memoir is

given below. With him may be said (in 1306) to have expired the direct

male line of the south country Frasers, after having been the most

considerable family in Peebles-shire during the Scoto-Saxon period of

our history, from 1097 to 1306. The ruins of Oliver castle, and the

castles of Fruid, Drummelzier, and Niedpath, (views of the last two may

be seen in Grose’s Antiquities,) attest their ancient greatness. Sir

Simon had two daughters, who divided his extensive possessions between

them. The elder, Mary, married Sir Gilbert Hay of Locherworth, ancestor

of the noble family of Tweeddale, on whom devolved, in her right, the

office of sheriff of Peebles. The younger became the wife of Sir Patrick

Fleming, progenitor of the earls of Wigton. Each of these families

quartered the arms of Fraser with their paternal arms.

The male representation of the principal family of Fraser devolved, on

the death of the great Sir Simon, on the next collateral heir, his

uncle, Sir Andrew, second son of Sir Gilbert Fraser, above mentioned. In

June 1291 he swore a forced allegiance to King Edward the First at

Dunfermline, and he was present when Baliol did homage to Edward, 26th

December 1292. He possessed the lands of Touch in Stirlingshire, which

it is probable were conferred on him when he became sheriff of that

county. He had also received from King Edward the First the manor of

Struthers and other lands in Fife. He and his son are frequently

mentioned in the annals of the period for their valorous exploits in

defence of their country against the English usurper. He is supposed to

have died about 1308, surviving his renowned nephew, Sir Simon, only two

years. He was, says the historian of the family, “the first of the name

of Fraser who established an interest for himself and his descendants in

the northern parts of Scotland, and more especially in Inverness-shire,

where they have ever since figured with such renown and distinction.” [Anderson’s

Hist. Acc. p. 35.] He married a wealthy heiress in the county of

Caithness, then and for many centuries thereafter comprehended within

the sheriffdom of Inverness, and in right of his wife he acquired a very

large estate in the north of Scotland. He had four sons, namely, Simon,

the immediate male ancestor of the lords Lovat (see LOVAT, Lord), and

whose descendants and dependents (the clan Fraser), after the manner of

the Celts, took the name of MacShimi, or sons of Simon; Sir Alexander,

who obtained the estate of Touch, as the appanage of a younger son, of

whom afterwards; and Andrew, and James, slain with their brother, Simon,

at the disastrous battle of Halidonhill, 22d July 1338.

The second son, Sir Alexander, swore fealty to Edward the First at

Berwick, 28th August, 1296. Among sixteen persons of the name

of Fraser, Frizel, or Fresle, whose names occur in the Ragman Roll as

having sworn fealty to King Edward, was Sir Richard Freser, styled del

Conte de Dumfries, who was probably a cousin of the great Sir Simon

Fraser. Sir Alexander joined King Robert at his coronation in March

1306, and was taken prisoner by the English at the battle of Methven, 19th

June following. He soon, however, recovered his liberty, and was with

Bruce in most of his battles, and particularly at Bannockburn. From that

monarch he received charters of various lands in the shires of

Kincardine, Stirling, and Aberdeen, and was sheriff of Kincardine. His

signature appears at the famous letter sent to the Pope in 1320,

asserting the independence of Scotland. Alexander Frisel was one of the

guarantees of a truce with the English 1st June 1323. He

married, about 1316, Lady Mary Bruce, a sister of King Robert, and widow

of Sir Niel Campbell of Lochow, and held the appointment of great

chamberlain of Scotland from 1325 to the death of his royal

brother-in-law in 1329. He fell at the battle of Duplin, 12th

August 1332. His line terminated, before 1355, in a female descendant,

Margaret, who inherited all his estates, and carried them into other

families. She married Sir William Keith, great marischal of Scotland;

and their son, John Keith, left by his wife, a daughter of King Robert

the Second, one son, Robert, whose daughter and heiress, Jean, married

Alexander, first earl of Huntly, on which account (as the dukes of

Gordon, before that title was extinct, did) the marquises of Huntly,

quarter the Fraser arms with their own.

_____

The ancient family of the Frasers of Philorth, in Aberdeenshire, who

have enjoyed since 1669 the title of Lord Saltoun, is immediately

descended from William, son of an Alexander Fraser, who flourished

during the early part of the fourteenth century, and inherited from his

father the estates of Cowie and Durris in Kincardineshire. This William

is stated erroneously in Douglas’ Peerage, (Wood’s edition, vol. ii. p.

473,) to have been a son of Sir Alexander, the chamberlain, above

mentioned. On the 7th July 1296, among other barons of that

part of the country, he swore fealty to Edward the First, at Fernel, now

Farnel, in Forfarshire, being described as “the son of the late

Alexander Fraser.” His father, therefore, must have been dead long

before Sir Alexander, the chamberlain, commenced his career. [Anderson’s

Hist. Acc. of the Frasers, p. 38, note.] From the loss of documents,

the precise relationship between him and the original Frasers of

Tweeddale cannot now be ascertained. William Fraser was one of the party

who, under the knight of Liddesdale, took by stratagem the castle of

Edinburgh, 17th April 1341. He was killed at the battle of

Durham, 17th October 1346.

His son, Sir Alexander Fraser of Cowie, had a safe-conduct, 13th

October 1366, to go to England, with eight in his company, to study at

the university of Oxford. From David the Second he had a grant of the

office of sheriff of Aberdeen. He signalized himself at the battle of

Otterbourne in 1388, and died not long after 1408. His wife was Lady

Janet Ross, second daughter and coheiress of William, earl of Ross, and

from her sister, Euphemia, countess of Ross, and her husband, Sir Walter

de Lesley, he had charters of various lands in the earldom of Ross, the

whole being called the barony of Philorth, which thenceforth became the

chief designation of the family. By Lady Janet he had a son, Sir

William, who succeeded him. By a second wife, Elizabeth, daughter of Sir

David de Hamilton of Cadzow, he had another son, Alexander, ancestor of

Sir Peter Fraser of Durris, whose daughter and heiress, Carey, was the

first wife of Charles Mordaunt, the celebrated earl of Peterborough and

Monmouth.

Sir William Fraser of Philorth, the elder son, succeeded his father

before 1413, when he sold the barony of Cowie to William Hay of Errol,

constable of Scotland. He died before 1441. By his wife, Lady Mary or

Eleanor Douglas, second daughter of the third earl of Douglas, he had a

son, Sir Alexander, and a daughter, Agnes, married, in 1423, to Sir

William Forbes of Kinnaldie, who obtained with her the barony of

Pitsligo.

The son, Sir Alexander Fraser of Philorth, was knighted by King James

the Second, and accompanied his kinsman, the eighth earl of Douglas, to

the jubilee at Rome in 1450. He died 7th April 1482. He had

two sons; Alexander, and James. The latter obtaining from his father the

lands of Memsey, was ancestor of the Frasers of Memsey, an estate which,

after being in their possession for upwards of three centuries, was sold

by the late Col. Fraser to Lord Saltoun.

Alexander, the elder son, was succeeded by his son, Sir William Fraser

of Philorth, who died at Paris 5th September 1513. His son,

Alexander Fraser of Philorth, (died 12th April 1569,) had

four sons. Alexander, the eldest, died in 1564, before his father,

leaving (by his wife, Lady Beatrix Keith, fifth daughter of the third

earl Marischal) a son, named after him. William the second son, was

ancestor of the Frasers of Techmuiry. Thomas, the third son, had a

charter of the lands of Strathechin or Strichen, in Aberdeenshire, 11th

May 1558. He had two daughters, coheiresses. John, the fourth son, a

bachelor of divinity, was abbot of Noyon or Compeigne in France, and in

1596, was elected rector of the university of Paris, where he died 19th

April 1609. He was the author of several treatises in philosophy, and of

the following two works, namely, ‘An Offer to Subscribers to the

Ministers of Scotland’s Religion, if they can prove themselves to have

the True Kirk,’ Paris, 1604, 8vo; ‘Epistles to the Ministers of Great

Britain, against Subscription to their Confession of Faith,’ Paris,

1605, 8vo.

Sir Alexander Fraser of Philorth, the son of the rector’s eldest

brother, succeeded his grandfather in 1569, and in the following year he

laid the foundation of the castle of Fraserburgh, which became the chief

residence of the family. He was a man of great public spirit, and to him

the town of Fraserburgh owes its municipal existence, as in October 1613

he got it erected into a burgh of regality, after an unavailing attempt

on the part of the magistrates and council of Aberdeen to prevent it.

The parish in which it is situated was originally called Philorth, but

the name was changed to Fraserburgh, in honour of Sir Alexander the

superior. The cross, the jail – now a ruinous edifice – and the

court-house, were erected by him. In 1592 he obtained a charter from the

Crown, containing powers to erect and endow a college and university at

Fraserburgh; and in 1597, the General Assembly recommended Mr. Charles

Ferme, then minister of Fraserburgh, to be principal, but nothing

further was ever done in the matter. An old quadrangular tower of three

stories, which formed part of a large building intended for the proposed

college, still stands at the west end of the town. Sir Alexander was in

great favour with King James the Sixth, to whom he advanced several

large sums of money, about the time of his marriage with the princess

Anne of Denmark. He was knighted in 1594, at the baptism of Prince

Henry, and died at Fraserburgh, 12th April 1623. A portrait

of him by Jameson is at Philorth house, near Fraserburgh, the seat of

his descendant Lord Saltoun. From another painting in the possession of

Mr. Urquhart of Craigston, an engraving was taken for Pinkerton’s

Scottish Gallery of Portraits, (vol. ii.) Of which the subjoined is a

woodcut:

[woodcut of Sir Alexander Fraser]

Sir

Alexander married Magdalen, only daughter of Sir Walter Ogilvy, of

Dunlugas, and had four sons and three daughters. Thomas, the youngest

son, was an antiquary, and wrote a history of the family.

The eldest son, also Sir Alexander, married Margaret, eldest daughter of

George, seventh Lord Abernethy of Saltoun, and, with two daughters, had

a son, Sir Alexander Fraser of Philorth, who, on the death of his

cousin, Alexander, ninth Lord Abernethy of Saltoun, in 1669, succeeded

to that peerage as heir of line, and became tenth Lord Saltoun. See

SALTOUN, Lord.

_____

FRASER, Baron,

a title (now dormant) in the peerage of Scotland, conferred by patent,

dated at Holyroodhouse, 29th June 1633, on Andrew Fraser, son

of Andrew Fraser of Kilmundy, Stanywood, and Muchells, Aberdeenshire,

descended from a branch of the house of Philorth, to him and his heirs

male for ever, bearing the name and arms of Fraser. He died 10th

December 1636.

His son, also named Andrew, second Lord Fraser, supported the cause of

the Covenant, and when Montrose proceeded to Aberdeen on the 30th

March 1639, with a commission from the Tables, (as the boards of

representatives, chosen respectively by the nobility, gentry, burghs,

and clergy, were called,) he was joined among others by Lord Fraser. On

the departure of Montrose’s army to the south, the Covenanters of the

north appointed a committee meeting to be held at Turriff on Wednesday,

24th April, consisting of the earls Marischal and Seaforth,

Lord Fraser, the master of Forbes, and some of their kindred and

friends. The meeting was afterwards adjourned till the 20th

May, which led to the historical incident styled “the Trot of Turray,”

the old name of Turriff, which is distinguished as the place where blood

was first shed in the civil wars. On the 11th of June

following, the royalist army under the Viscount Aboyne proceeded to the

house of Muchells, belonging to Lord Fraser, but hearing of a rising in

the south, Aboyne abandoned his intention of besieging it, and returned

to Aberdeen. Lord Fraser was one of the parliamentary commissioners

appointed 19th July 1644, for suppressing the insurrection in

the north, and for proceeding against rebels and malignants. In the

following year he was also one of the committee of Estates, and in 1649

he was a member of the committee for putting the kingdom in a posture of

defence. He died 24th May 1674. By his wife, a daughter of

Haldane of Gleneagles, he had a son, Andrew, third Lord Forbes, who

married Catherine, third daughter of Hugh eighth Lord Lovat, relict of

Sir John Sinclair of Dunbeath, and of Robert first viscount of Arbuthnot.

He died about the end of 1682.

His son, Charles, fourth Lord Fraser, was tried before the high court of

justiciary at Edinburgh, 29th March 1693, on a charge of high

treason, for proclaiming King James at the cross at Fraserburgh in June

or July 1692, drinking his health and that of his son, the pretended

prince of Wales, forcing others to do the same, and cursing King William

and his adherents, amid the firing of guns and pistols, and the

brandishing of swords. He was found guilty only of drinking the healths

of King James and his son. On the 16th May the court fined

him for the offence two hundred pounds. On his trial the lord advocate,

Sir James Stewart, protested for an assize of wilful error, if the jury

should acquit the prisoner, which, if acceded to, would have subjected

them to an indictment for giving an impartial and unbiased verdict in

his favour; but Lord Fraser, on his part, protested in the contrary,

because the committee of Estates, which had declared King James to have

‘forfaulted’ the crown and bestowed the same on William and Mary,

solemnly enacted and declared ‘that assizes of error are a grievance.’ [Arnot’s

Criminal Trials, pp. 77 and 78.] Four of the jury, evidently

apprehensive of being brought to an assize for the verdict delivered in,

desired it to be marked in the record that they found the proclamation

proved in terms of the indictment. These four were the master of Forbes,

Sir Alexander Gilmore of Craigmillar, Patrick Murray of Livingstone, and

James Ellis of Southside. Lord Bargeny was chancellor of the jury, and

it deserves to be noticed, as an indication of the feeling of the times,

that seven peers and eight gentlemen of distinction who were summoned as

jurors were fined a hundred merks each for not obeying the citation. The

middle verdict of ‘not proven,’ which is only known in the criminal

courts of Scotland, appears to have originated in the power then

possessed by the lord advocate, and too frequently exercised before the

Revolution, of subjecting an acquitting jury to an assize of wilful

error, to save them from the consequences of one of not guilty, and

prevent them from giving in one of guilty, contrary to the evidence and

their own consciences.

Lord Fraser took the oaths and his seat in parliament, 2d July 1695, and

in the parliament of 1706, he supported the union with England; but

engaged in the rebellion of 1715, and after its suppression, kept

himself concealed till his death, which happened 12th October

1720, owing to a fall from a precipice near Banff, by which his skull

was fractured, and he died immediately. He married Lady Marjory Erskine,

second daughter of the seventh earl of Buchan, relict of Sir Simon

Fraser of Inverallochy, but had no issue. The estate of Castle Fraser

was left by his lordship to her children by her first husband (see next

article). No heir male general has yet become a claimant for the title

of Lord Fraser.

_____

The family of Fraser of Castle Fraser, in Ross-shire, are descended, on

the female side, from the Hon. Sir Simon Fraser of Inverallochy, second

son of Simon, eighth Lord Lovat, but on the male side their name is

Mackenzie. Sir Simon’s grandson, Charles fraser, Esq. of Inverallochy,

heir of line to his grandmother, Lady Marjory Erskine, Lady Fraser, he

had no sons, and his eldest daughter, Martha, married Colin Mackenzie of

Kilcoy, by whom she had, with other issue, Charles, whose only son was

Sir Colin Mackenzie of Kilcoy, baronet, and Alexander Mackenzie, who

succeeded his mother in the estate of Inverallochy, and her youngest

sister, Elizabeth, in that of Castle Fraser, when he assumed the

additional surname of Fraser by royal license. He early entered the

army, and distinguished himself at the siege of Gibraltar. On the first

battalion of the 78th Highlanders, or Ross-shire Buffs,

being embodied in February 1793, he was appointed lieutenant-colonel of

it, and in September 1794 joined an expedition under Major-general Lord

Mulgrave, the object of which was to occupy Zealand. On reaching

Flushing, the 78th, with other regiments, was ordered to

reinforce the duke of York’s army on the Waal. It afterwards became part

of the garrison of Nimeguen, to which place the enemy had laid siege.

After the evacuation of that place, the 78th entered the

third brigade of reserve, which was under the command of

Lieutenant-colonel Mackenzie Fraser. With his regiment he was engaged in

all the subsequent movements of the army, and in the retreat to Bremen.

He afterwards served in La Vendee, and in India, which he left in 1800.

When the second battalion of the regiment was raised in 1804, he was

made colonel of it. Early in 1807, when major-general, he commanded the

armament which was fitted out in Sicily for the purpose of occupying

Alexandria, Rosetta, and the adjoining coast of Egypt. The force under

his command on this occasion consisted of a detachment of artillery, the

20th light dragoons, the 31st, 35th, 78th,

and two other regiments. On the 16th of March he arrived with

a portion of his force off the Arab’s Tower to the west of Alexandria,

and having disembarked his troops, the town, on being summoned,

surrendered to him on the 20th of that month. He was

subsequently promoted to be lieutenant-general, and sat in several

parliaments as member for Ross-shire, his native county. He died in

1809, having married Helen, sister of Francis Lord Seaforth, and, with 2

daughters, had two sons; Charles, his heir, and Frederic Alexander

Mackenzie, lieutenant-colonel in the army, and assistant quarter-master

general to the forces in Canada, married 1st, second daughter

of Hume MacLeod of Harris, issue; 2dly, a daughter of Sir Charles Bagot,

Governor of Canada.

The elder son, Charles Fraser of Inverallochy and Castle Fraser, born

June 9, 1792, entered the army young, and served in the Peninsula in

1808-9, in the 52d foot, and in 1812, in the Coldstream guards, in which

regiment he was a captain. He was also colonel of the Ross-shire

militia. He was M.P. for Ross-shire from 1815 to 1819. He married Jane,

4th daughter of Sir John Hay, Bart. of Hayston, issue, 4 sons

and 5 daughters.

_____

The proper Highland clan Fraser, – in Gaelic Na Friosalaich, –

whose badge is the yew, and battle-cry was “Castle Downie,” (the

residence of their chief, from Duna, a camp or fortified

dwelling,) was that headed by the Lovat branch in Inverness-shire, as

above mentioned. Simon being the name of the first of them who settled

in the Highlands, and a common name for their chiefs, they adopted the

Gaelic designation of MacShimei, that is, the sons of Simon. They are

also sometimes called MacImmies. Unlike the Aberdeenshire or Saltoun

Frasers, the Lovat branch, the only branch of the Frasers that became

Celtic, founded a tribe or clan, and all the natives of the purely

Gaelic districts of the Aird and Stratherrick came to be called by their

name. The Simpsons, sons of Simon, are also considered to be descended

from them, and the Tweedies of Tweeddale are supposed, on very plausible

grounds, to have been originally Frasers. Logan’s conjecture that the

name of Fraser is a corruption of the Gaelic Friosal, from

frith, a forest, and siol, a race, the th being

silent, (that is, the race of the forest,) however pleasing to the clan

as proving them an indigenous Gaelic tribe, may only be mentioned here

as a mere fancy of his own.

The Frasers had their own share of clan feuds and battles, but the most

remarkable as well as the most sanguinary conflict in which they were

ever engaged was in 1544, with the MacDonalds of Clanranald, who had put

their chief Dougal MacRanald to death, and excluded his children from

the succession. Lord Lovat being the uncle of the young Ranald, Dougal’s

eldest son, called Ranald Galda, or the stranger, his cause was espoused

by the Frasers, four hundred of whom, the flower of the clan, with Lord

Lovat at their head, joined the earl of Huntly, the king’s lieutenant in

the north, when, with a numerous force, he marched to crush a threatened

insurrection of the Clanranald. After penetrating as far as Inverlochy

in Lochaber, and putting Ranald Galda in possession of Moydert, Huntly

retraced his steps, and on arriving at the mouth of Glenspean, Lovat

left him with his own vassals, accompanied by Ranald Galda and a few

followers of the latter. Near the head of the loch they were attacked by

a body of the Clanranald, amounting to nearly five hundred men. The

battle that ensued was one of the most bloody and destructive in clan

annals. It began with the discharge of arrows at a distance, but when

these were spent, both parties rushed to close combat, and attacked each

other furiously with their two-handed swords and Lochaber axes. So great

was the heat of the weather, it being the month of July, that the

combatants threw off their coats, and fought in their shirts; whence the

battle received the name of Blar-nanlein, ‘The field of shirts.’ All the

Frasers were killed, except one gentleman, James Fraser of Foyers (who

was severely wounded, and left for dead), and four common men, while it

is said, though this is considered incorrect, that only eight of the

Macdonalds survived the battle. The bodies of Lord Lovat, his son, the

Master, who had joined his father soon after the commencement of the

action, and Ranald Galda, were, a few days after, removed by a train of

mourning relatives, and interred at the priory of Beauly in the Aird. [Gregory’s

Highlands, p. 161.]

The clan Fraser formed part of the army of the earl of Seaforth when in

the beginning of 1645 that nobleman advanced to oppose the great

Montrose, who designed to seize Inverness, previous to the battle of

Inverlochy, in which the latter defeated the Campbells under the marquis

of Argyle in February of that year. After the arrival of King Charles

the Second in Scotland in 1650, the Frasers, to the amount of eight

hundred men, joined the troops raised to oppose Cromwell, their chief’s

son, the master of Lovat being appointed one of the colonels of foot for

Inverness and Ross. In the summer of 1652 they submitted to Monk, and as

Balfour says, “condescendit to pay cesse,” while other Highland clans

stood out, and laughed the English to scorn. [Balfour’s Annals,

vol. iv. p. 349.] In the rebellion of 1715, under their last famous

chief, Simon Lord Lovat (beheaded at Towerhill in 1747, of whom a memoir

is given below), they did good service to the government by taking

possession of Inverness, which was then in the hands of the Jacobites.

In 1719 also, at the affair of Glenshiel, in which the Spaniards were

defeated on the west coast of Inverness-shire, the Frasers fought

resolutely on the side of government, and took possession of the castle

of Brahan, the seat of the earl of Seaforth. On the breaking out of the

rebellion of 1745, they did not at first take any part in the struggle,

but after the battle of Prestonpans, on the 21st September,

Lord Lovat “mustered his clan,” and their first demonstration in favour

of the Pretender was to make a midnight attack on the castle of

Culloden, but found it garrisoned and prepared for their reception. On

the morning of the battle of Culloden six hundred of the Frasers, under

the command of the master of Lovat, a fine young man of nineteen,

effected a junction with the rebel army, and behaved during the action

with characteristic valour. When the Highlanders were forced to retreat,

the Frasers marched off with banners flying and pipes playing in the

face of the enemy. After the battle Charles Fraser, younger of

Inverallochy, the lieutenant-colonel of the Fraser regiment, was

savagely slain by order of the duke of Cumberland. When riding over the

field, the duke observed this brave youth lying wounded. Raising himself

upon his elbow, he looked at the duke, when the latter thus addressed

one of his officers, who afterwards became a more distinguished

commander than himself: “Wolfe, shoot me that Highland scoundrel who

thus dares to look on us with so insolent a stare.” Wolfe replied, that

his commission was at his royal highness’ disposal, but that he would

never consent to become an executioner. Other officers refusing to

commit this act of butchery, a private soldier, at the inhuman command

of the duke, shot the hapless youth before his eyes.

Lord Lovat’s eldest son, Simon Fraser, master of Lovat, afterwards

entered the service of government, and rose to the rank of

lieutenant-general in the army. He was at the university of St. Andrews,

pursuing his studies, when the rebellion broke out, and was sent for by

his father to head the clan in support of the Pretender, which he most

reluctantly did. It was stated by a witness on Lord lovat’s trial, that

while he was preparing one of his lordship’s deceptive letters to the

lord president Forbes, complaining of the obstinacy of his son in

rushing into the rebellion, the master of Lovat came in, and on reading

what he had written at the dictation of his father, said, “If this

letter goes, I will go and put the saddle on the right horse.” After the

battle of Culloden, he surrendered himself, and was confined in the

castle of Edinburgh till August 1747, when he proceeded to Glasgow,

there to remain during the king’s pleasure. Being proved to have been

forced into the rebellion, he in 1750 received a full and free pardon

from government. Soon after he refused an offer which was made to him of

a regiment in the French service; but he requested permission to be

employed in the British army, and in 1756, though not possessed of an

inch of land, his father’s estates being under forfeiture, in a few

weeks he raised among his own kinsmen and clan, a regiment of fourteen

hundred men, called the 78th or Fraser’s Highlanders, of

which he was appointed lieutenant-colonel, 5th January 1757.

On the regiment’s arrival at Halifax the following June, as the Highland

garb was judged unfit for the climate of North America, it was proposed

to change it for some warmer uniform, but the officers and soldiers

having set themselves against the plan, and being strongly supported in

their opposition by Colonel Fraser, it was abandoned. “Thanks to our

gracious chief,” said a veteran of the regiment, “we were allowed to

wear the garb of our fathers, and, in the course of six winters, showed

the doctors that they did not understand our constitution; for, in the

coldest winters, our men were more healthy than those regiments who wore

breeches and warm clothing.” He distinguished himself at Louisburg, and

in the attack on Quebec, where the regiment suffered much, and where he

himself was wounded. In the second battle on the Heights of Abraham,

under General Murray, Wolfe’s successor, Colonel Fraser commanded the

left wing of the British army, and was again wounded. In 1761, during

his absence in America, he was chosen M.P. for the county of Inverness,

and was constantly rechosen till his death. In the force sent to

Portugal, in 1762, to defend that kingdom against the Spaniards, he was

a brigadier-general. His regiment having been disbanded, Fraser’s

Highlanders were, in 1773, after the breaking out of the American

revolutionary war, again embodied, under the auspices of their former

chief, the Hon. General Fraser, who, in reward of his services, had, the

previous year, received from George the Third, a grant of the forfeited

Lovat estates, his own patrimony. The title, however, of Lord Lovat, was

not restored. The new regiment, of which he was appointed colonel,

consisted of two battalions of two thousand three hundred and four

Highlanders, and were numbered the 71st. When mustered at

Glasgow in April 1762, for embarkation to America, a body of one hundred

and twenty men, who had been raised on the forfeited estate of Lochiel,

with the view of securing the latter a company, finding that their own

chief had not, from illness, been able to join the regiment, hesitated

to embark without him, but General Fraser addressing them in Gaelic,

succeeded in removing their scruples. General Stewart relates that when

he had finished speaking, an old Highlander present, who had accompanied

his son to Glasgow, walked up to him, and with that easy familiar

intercourse which in those days subsisted between the Highlanders and

their superiors, shook him by the hand, exclaiming, “Simon, you are a

good soldier, and speak like a man; as long as you live Simon of Lovat

will never die;” alluding to the general’s address and manner, which, as

was said, resembled much that of his father, Lord Lovat. He was

eventually promoted to the rank of lieutenant-general, and died, without

issue, 8th Feb. 1782. Mrs. Grant of Laggan states that in him

a pleasing exterior covered a large share of his father’s character, and

that “no heart was ever harder, – no hands more rapacious than his.”

General Fraser was succeeded by his half-brother, Colonel Archibald

Campbell Fraser of Lovat, appointed consul-general at Algiers in 1766,

and chosen M.P. for Inverness-shire, on the general’s death in 1782. By

his wife, Jane, sister of William Fraser, Esq. of Leadclune, F.R.S.,

created a baronet, 27th November 1806, he had five sons, all

of whom he survived. On his death, in December 1815, the male

descendants of Hugh ninth Lord Lovat, became extinct, and the male

representation of the family, as well as the right to its extensive

entailed estates, devolved on the junior descendant of Alexander sixth

lord, Thomas Alexander Fraser, of Lovat and Struchen, who claimed the

title of Lord Lovat in the peerage of Scotland, and in 1837 was created

a peer of the United Kingdom, by that of Baron Lovat of Lovat. [See

LOVAT of Lovat, Lord.]

His lordship’s great-grandfather, Alexander Fraser of Strichen, the son

of Thomas Fraser of Strichen and Emilia Stewart, second daughter of

James Lord Doune, was an eminent judge of the court of session. He

passed advocate 23d June 1722, and was afterwards one of the

commissaries of Edinburgh. Admitted a lord of session 5th

June 1730, he took his seat by the title of Lord Strichen, and was

appointed a lord of justiciary, 11th June 1735. Being one of

the judges at the autumn circuit court at Inverness that year, he was

met a few miles from the town, by his kinsman Simon Lord Lovat, attended

by a great retinue, eager to honour and congratulate him on his new

judicial dignity. Having been appointed general of the Scottish Mint in

1764, he resigned his seat as a justiciary judge, but retained his

office in the court of session till his death. He is remarkable for

having sat the unusually long period of forty-five years on the bench.

At the time of the great Douglas cause in 1768, he was the oldest

Scottish judge, being of no less than twenty-four years longer standing

than any of his brethren. He is supposed to have been one of the judges

at the famous trial of Effie Deans in 1736, on which Scott’s novel of

‘The Heart of Mid Lothian’ is founded. He married in 1731, the countess

of Bute, and died at Strichen house, Aberdeenshire, 15th

February 1776, at the age of 76. [Scots Mag. vol. xxxvii. p.

111.]

_____

Sir William Fraser, of Leadclune, created a baronet in 1806, above

mentioned, descended from Alexander, 2d son of Hugh 2d Lord Lovat, was

in the naval service of the East India Company, and commanded two of

their ships, ‘the Lord Mansfield,’ in 1772, which was lost in coming out

of the Bengal river in 1773; and ‘the Earl of Mansfield,’ from 1777 to

1785. He had 3 sons and 11 daughters, and died 10th Feb.

1818.

His eldest son, Sir William Fraser, second baronet, died unmarried, 23d

Dec. 1827, in India, where he had an official appointment. Sir William’s

surviving brother, Sir James John Fraser, third baronet, a

lieutenant-colonel in the army, served with the 7th hussars

in Spain, and was on the staff at Waterloo. He married Charlotte Anne,

only daughter of David Craufurd, Esq., and niece of the gallant

Major-general Robert Craufurd, killed at Cuidad Rodrigo. He died 5th

June 1834, leaving three sons.

The eldest son, Sir William Augustus Fraser, fourth baronet, born in

1826, was educated at Christ church, Oxford, and in 1847 was appointed

an officer in the first life guards. In 1852 he was elected M.P. for

Barnstaple. His brother, Charles Craufurd, major in the army (1858), was

at one time aide-de-camp to the lord-lieutenant of Ireland, and highly

distinguished himself in India. The 3d brother, James Keith, is a

captain first life guards (1860).

FRASER, SIR SIMON,

a renowned warrior and patriot, the son of Sir Simon Fraser, last lord

of Tweeddale and Oliver castle, Peebles-shire, who died in 1299, and

Mary, eldest daughter of Sir John Bisset of Lovat, the chief of the

Bissets, was born in 1257. With his father and family he adhered

faithfully to the interest of John Baliol, till the latter himself

betrayed his own cause. In 1296, when Edward the First invaded Scotland,

Sir Simon was one of those true-hearted patriots whom the English

monarch carried with him to England, where he continued close prisoner

for eight months. In Jun 1297 he and his cousin, Sir Richard Fraser,

submitted to Edward, and engaged to accompany that monarch in his

designed expedition to France, but requested permission to go for a

short time to Scotland, pledging themselves to deliver up their wives

and children for their faithful fulfilment of the engagement.

On his return to his native country, Sir Simon, not considering his

forced obligation with King Edward binding in conscience, joined Sir

William Wallace, guardian of the kingdom, and gave so many distinguished

proofs of his valour and patriotism, that when that illustrious hero, in

a full assembly of the nobles at Perth, resigned his double commission

of general of the army and guardian of the kingdom, Sir Simon Fraser was

chosen his successor in the post of commander of the Scots army, while

Sir John Comyn of Badenoch, Wallace’s greatest enemy, was appointed

guardian, on account of his near relation to the crown.

In summer 1302, two separate English armies were sent into Scotland, the

one commanded by King Edward in person, and the other by the prince of

Wales, his son (afterwards the unfortunate Edward the Second), but the

Scots, prudently avoiding a regular engagement, contented themselves

with intercepting the English convoys, and cutting off detached parties

of the enemy. In the meantime a truce was agreed upon till November 30,

which was prolonged till Easter 1303. But the English general broke the

truce, and passed the borders in February, at the had of thirty thousand

well-appointed soldiers. Meeting with no opposition on their march, for

the convenience of forage, and to enable them to harass the country the

more effectually, they divided into three bodies, and on the 24th

of that month, advanced to Roslin near Edinburgh, where they encamped at

a considerable distance from each other. The Scots leaders, Sir John

Comyn and Sir Simon Fraser, hastily collecting about ten thousand men

together, marched from Biggar during the night, and next day defeated in

succession the three divisions of the English army, or rather the three

separate armies of English. This happened February 25, 1302-3. This

victory raised the character of the Scots for courage all over Europe;

and Sir Simon Fraser’s conduct on the occasion is spoken of in high

terms by our ancient historians. Fordun, in his Scotichronicon, says,

that he was not only the main instrument in gaining this remarkable

battle, but in keeping Sir John Comyn to his duty as guardian during the

four years of his administration.

Highly incensed at this threefold defeat at Roslin, Edward entered

Scotland in May following, at the head of a vast heterogeneous host,

consisting of English, Irish, Welsh, Gascons, and some recreant Scots.

Not being able to cope with such a force in the open field, most of the

nation betook themselves to strong castles and mountains inaccessible to

all but themselves, while the English monarch penetrated as far as

Caithness. Being thus in a manner in possession of the country, the

guardian, Sir John Comyn, and many of the nobility, submitted to him in

February 1303-4; but Sir Simon Fraser refusing to do so, was among those

who were expressly excepted from the general conditions of the

capitulation made at Strathorde on the 9th of that month. It

was also provided that he should be banished for three years not only

from Scotland but from the dominions of Edward, including France; and he

was ordered, besides, to pay a fine of three years’ rent of his lands.

Sir Simon, in the meantime, concealed himself in the north till 1306,

when he joined Robert the Bruce, who in that year asserted his right to

the throne. It is probable that he was present at King Robert’s

coronation at Scone, as we find him at the fatal battle of Methven soon

after; on which occasion the king owed his life to his valour and

presence of mind, having been by him three times rescued and remounted,

after having had three horses killed under him. He escaped with the

king, whom he attended into Argyleshire, and was with him at the battle

of Dalry. On the separation of the small party which accompanied King

Robert, Sir Simon, it is thought, also left him for a short period. But

after the king had lurked for some time among the hills, Sir Simon, with

Sir Alexander his brother, and some of his friends, rejoined him, when

they attacked the castle of Inverness, and then marched through the

Aird, afterwards the country of the clan Fraser, to Dingwall, taking the

castle there, and thereafter through Moray, all the fortresses

surrendering to Bruce on their way.

In 1307 Sir Simon was, with Sir Walter Logan of the house of Restalrig,

treacherously seized by some of the adherents of the earl of Buchan, one

of the chiefs of the Comyns, who sent them in irons to London. When such

men as the earl of Athol; Niel, Thomas, and Alexander Bruce, the king’s

brothers; Sir Christopher Seton, and his brother John; Herbert Norham;

Thomas Bois; Adam Wallace, brother of Sir William, and that great hero

himself, were put to death, Sir Simon Fraser and Sir Walter Logan had

nothing to expect from Edward’s mercy. Accordingly they were both

beheaded, but Sir Simon’s fate was more severe than was than of any of

the rest. He was kept in fetters while in the Tower, and on the day of

execution he was dragged through the streets as a traitor, hanged on a

high gibbet as a thief, and his head cut off as a murderer. His body,

after being exposed for twenty days to the derision of the mob, was

thrown across a wooden horse, and consumed by fire, while his head was

fixed on the point of a lance, and placed near that of Sir William

Wallace on London Bridge. Against these merciless executions, which were

more dishonouring to Edward’s memory than to the illustrious patriots,

his victims, the lord chief justice of England remonstrated with

dignity, declaring to the savage monarch, “That he had no authority to

put prisoners of war to death.” But Edward turned a deaf ear to all such

remonstrances. For Simon’s issue see the previous.

FRASER, SIR ALEXANDER,

physician to Charles the Second, belonged to the ancient family of

Fraser of Durris. He was educated in Aberdeen, and by his professional

gains and fortunate marriage was enabled to re-purchase the inheritance

of his forefathers. We are told that “he was wont to compare the air of

Durris to that of Windsor, reckoned the finest in England.” He

accompanied Charles the second in his expedition to Scotland in 1650,

and seems to have been particularly obnoxious to the Covenanters. On the

27th September of that year he and several others, described

as “profaine, scandalous, malignant, and disaffected persons,” were

ordered by the committee of Estates to remove from the court within

twenty-four hours, under pain of imprisonment. His name is conspicuous

in the Rolls of the Scottish parliament during the reign of Charles the

Second, and occurs occasionally in the pages of Papys. Spottiswoode, in

his History of the Church of Scotland, speaks highly of his learning and

medical skill. He died in 1681.

FRASER, SIMON, 12th Lord Lovat,

one of the most remarkable of the actors in the rebellion of 1745, was

the second son of Thomas Fraser, styled of Beaufort, by Sybilla,

daughter of Macleod of Macleod, and was born in 1667. Beaufort was

another name of Castle Counie, the chief seat of the family, and did not

belong to Simon’s father at the time of his birth. He had a small house

in Tanich, in the parish of Urray, Ross-shire, where it is supposed that

the future Lord Lovat was born. At the proper age he became a student at

King’s college, Old Aberdeen, the favourite university of the Celts, and

in 1694, while prosecuting his studies, he accepted of a commission in

the regiment of Lord Murray, afterwards earl of Tullibardine, procured

for him by his cousin, Hugh Lord Lovat. Having, in 1626, accompanied the

latter to London, he found means to ingratiate himself so much with his

lordship, that he was prevailed upon to make a universal bequest to him

of all his estates in case he should die without make issue. On the

death of Lord Lovat soon after, Simon Fraser began to style himself

master of Lovat, while his father, “Thomas of Beaufort,” took possession

of the honours and estates of the family. To render his claims

indisputable, however, Simon paid his addresses to the daughter of the

late lord, who had assumed the title of baroness of Lovat, and having

prevailed on her to consent to elope with him, would have carried his

design of marrying her into execution, had not their mutual confident,

Fraser of Tenechiel, after conducting the young lady forth one winter

night in such precipitate haste, that she is said to have walked

barefooted, failed in his trust, and restored her again to her mother.

The heiress was then removed out of the reach of his artifices by her

uncle, the marquis of Athol, to his stronghold at Dunkeld.

Determined not to be baulked in his object, the master of Lovat resolved

upon marrying the lady Amelia Murray, dowager baroness of Lovat; but as

she would not consent to the match, he had recourse to compulsory

measures, and, entering the house of Beaufort, or Castle Dounie, where

the lady resided, he had the nuptial ceremony performed by a clergyman

whom he brought along with him, and immediately afterwards, it is said,

forcibly consummated the marriage before witnesses. He afterwards

conveyed her, her brother Lord Mungo Murray and Lord Saltoun, whom he

had forcibly seized at the wood of Bunchrew, on his return from a visit

to her at Castle Dounie, to the island of Aigas, where he kept them for

some time prisoners. Having by these proceedings incurred the enmity of

the marquis of Athol, who was the brother of the dowager Lady Lovat, he

was, in consequence of a representation made to the privy council,

intercommuned, letters of “fire and sword” were issued against him and

all his clan, and on Sept. 5, 1698, he and ten other persons of the name

were tried, in absence, before the high court of justiciary for high

treason, rape, and other crimes, when being found guilty of treason, to

which the lord advocate restricted the charges in the indictment, they

were condemned to be executed, and their lands declared forfeited. His

father having died in 1699, he assumed the title of Lord Lovat, but in

consequence of the proceedings against him he was compelled to quit the

kingdom. After a short stay in London, he went to France, for the

purpose of lodging a complaint against the marquis of Athol with the

exiled king at St. Germains; after which he had the address to obtain an

interview with King William, who was then at Loo in the United

Provinces; and having obtained, through the influence of the duke of

Argyle, a remission of his sentence, and a pardon of all crimes that

could be alleged against him, – which, however, was restricted, on

passing the Scottish seals, to the crime of which he had been found

guilty, – he ventured to return to Scotland. He was immediately cited

before the high court of justiciary, on 17th February 1701,

for the outrage done to the dowager Lady Lovat, and, not appearing, he

was outlawed. On the 19th February 1702 her ladyship

presented a petition against him for letters of intercommuning, for

levying the rents of the Lovat estates, which a second time were granted

against him and his abettors. He now deemed it advisable to return to

France, which he reached in July of that year, after the accession of

Queen Anne to the throne. Previous to his departure from Scotland, he

had visited several of the chiefs of clans and principal Jacobites in

the lowlands, and engaged them to grant him a general commission

engaging to take up arms in support of the Stuart cause; possessed of

which he immediately joined in all the intrigues of the exiled court of

St. Germains, and even managed to obtain some private interviews with

Louis the Fourteenth. By that monarch a valuable sword and some other

tokens of reminiscence were bestowed on him as a mark of his confidence.

He had also some meetings with two of the French ministers of state, on

a project which he had proposed to the ex-queen, Mary of Modena, acting

in her son’s name, a boy at that time only fourteen years of age, for

the invasion of Scotland and the raising of the Highland clans.

He returned to Scotland in 1703, with a colonel’s commission in the

Pretender’s service, and accompanied by John Murray, brother of Murray

of Abercairney, who was authorised to ascertain if Lovat’s

representations, as to the intentions of the Jacobite chiefs, had been

warranted by them. Immediately after his return he had interviews with

his cousin Stuart of Appin, Cameron of Lochiel, the laird of MacGregor,

Lord Drummond, and others, on the subject of a rising, but meeting with

little encouragement, he resolved to betray the whole plot to

government; which he did in a secret audience with the duke of

Queensberry, who was then at the head of Scottish affairs. On his

re-appearance in Scotland, letters of “fire and sword” had again been

issued against h im and his followers, and he prevailed on Queensberry

to grant him a pass to London, that he might be out of the reach of

danger. With his grace he had some more secret interviews in London, and

soon after he returned to France, by way of Holland, with the object of

obtaining for government further secret information about the projects

of the exiled court. In passing through Holland he assumed the disguise

of an officer in the Dutch service, but soon after his arrival in Paris,

he was, by the french government, at the instance of the exiled queen,

arrested, sent to the Bastille, and afterwards imprisoned for three

years in the castle of Angouleme, and seven years in the city of Saumur,

where he is said to have taken priest’s orders, and become a renowned

popular preacher.

After making many fruitless efforts to regain his liberty, – the exiled

court having refused to sanction his release, – he at last resolved, on

the death of Queen Anne, to endeavour to make his escape, which he

effected with the aid of Major Fraser, one of his kinsmen, who had been

sent over by his clan to discover where he was, and to learn his

intentions, in the event of an insurrection in favour of the Stuarts.

Reaching Boulogne in safety, and there hiring a boat, they sailed on 14th

November 1714, and after a storm, landed at Dover next afternoon. On his

arrival in London, he kept himself concealed for some time; but at the

instigation of his enemy the marquis of Athol, a warrant was issued

against him, and on the 11th of the following June, he was

arrested in his lodgings in Soho Square, and, with the major, kept for

some time in a sponging house, but at last obtained his liberty, on the

earl of Sutherland, John Forbes of Culloden, and some other gentlemen,

becoming bail for him to the extent of £5,000.

He remained in London till October 1715, when the rebellion having

broken out, he returned to Scotland as one of his brother john’s

attendants, being still under the sentence of outlawry. In a vindication

of his conduct addressed to Lord Islay he says, that on this occasion he

was taken prisoner at Newcastle, Longtown, near Carlisle, Dumfries, and

Lanark, but succeeded in reaching Stirling. He proceeded thence to

Edinburgh, to embark at Leith for the north, but had not been there two

house when he was apprehended by order of the lord justice clerk, and

would have been sent to the castle had he not been delivered, he does

not say how, by Provost John Campbell. A few days after he sailed from

Leith with John Forbes of Culloden, but their vessel was pursued and

fired upon by several large Fife boats in possession of the rebels. On

arriving in his own country, he was just in time to be of considerable

service to the royal cause and to his own interests. Joining two hundred

of his clan who were waiting for him under arms in Stratherrick, he

concerted a plan with the Grants, and Duncan Forbes of Culloden,

afterwards president of the court of session, for recovering Inverness

from the rebels, in which they were successful. For his zeal and

activity on this occasion he had his reward. The young baroness of Lovat

had married, in 1702, Alexander Mackenzie, younger of Prestonhall, who

thereupon assumed the name of Fraser of Fraserdale; but engaging in the

rebellion of 1715, he was obliged to leave the country, and being

outlawed and attainted, his liferent of the estate of Lovat was

bestowed, by a grant from the Crown, dated 23d August 1716, on Simon,

Lord Lovat, “for his many brave and loyal services done and performed to

his majesty,” particularly in the late rebellion. A memorial in his

lordship’s favour, signed by about seventy individuals, including the

earl of Sutherland, the members of parliament and the sheriffs of the

northern counties, having been presented to the king, George the First,

his pardon had been granted on the 10th of the preceding

March, and on the 23d June following he had a private audience with his

majesty. In 1721 he voted by list at the election of a representative

peer, when his title was questioned. His vote was again objected to at

the general elections of 1722 and 1727. In consequence of which, he

brought a declaration of his right to the title before the court of

session, and their judgment, pronounced July3, 1730, was in his favour.

To prevent an appeal, a compromise was entered into with Hugh Mackenzie,

son of the baroness, who, on the death of his mother, had assumed the

title, whereby, for a valuable consideration, he ceded to Simon Lord

Lovat his claim to the honours and his right to the estate after his

father’s death.

Although Lord Lovat had deemed it best for his own purposes to join the

friends of the government in 1715, he was, nevertheless, throughout his

whole career, a thorough Jacobite in principle; and in 1740 he was the

first to sign the Association for the support of the Pretender, who

promised to create him duke of Fraser, and lieutenant-general, and

general of the Highlands. On the breaking out of the rebellion in 1745,

he sent his eldest son, much against the young man’s inclination, with a

body of his clan to join the army under Prince Charles, while he himself

remained at home. After the disastrous defeat at Culloden, the young

Pretender took refuge, on the evening of the battle, at Gortuleg, the

house of one of the gentlemen of his clan, near the Fall of Foyers,

where his lordship was then living, and not at Castle Dounie, as

erroneously supposed by Sir Walter Scott. According to Mrs. Grant of

Laggan’s account of the meeting, Lovat expressed attachment to him, but

at the same time reproached him with great asperity for declaring his

intention to abandon the enterprise entirely. “‘Remember,” said he

fiercely, “your great ancestor, Robert Bruce, who lost eleven battles,

and won Scotland by the twelfth.” Lovat himself afterwards retired from

the pursuit of the king’s forces to the mountains, but not finding

himself safe there, he escaped in a boat to an island in Loch Morar.

Thither he was pursued, taken prisoner, being found concealed in a

hollow tree, with his legs muffled in flannel, and carried to London.

His trial for high treason commenced before the House of Lords, March 7,

1747, He was found guilty on Marcy 18; sentence of death was pronounced

next day; and he was beheaded on Tower Hill, April 9, 1747, in the

eightieth year of his age. His behaviour while in the Tower was cheerful

and collected. When advised by his friends to petition the king for

mercy, he absolutely refused, saying he was old and infirm, and his life

was not worth asking. His estates and honours were forfeited to the

Crown, but the former were restored in 1774 to h is eldest son, as

already mentioned earlier.

Lord Lovat’s appearance, in his old age, was grotesque and singular.

Besides his forced marriage with the dowager Lady Lovat above described,

he entered twice, during that lady’s life, into the matrimonial state;

first, in 1717, with Margaret, fourth daughter of Ludovick Grant of

Grant, by whom he had two sons and two daughters; and, secondly, in

1733, after that lady’s death, with Primrose, fifth daughter of John

Campbell of Mamore, brother to the duke of Argyle. By this lady he had

one son. The lady’s objections to the marriage he is said to have

overcome by the following stratagem: She received a letter purporting to

be from her mother, in a dangerous state of health, desiring her

presence in a particular house in Edinburgh. On hastening to the house

indicated, she found Lovat waiting for her there, when he informed her

that the house was devoted to purposes which stamped infamy on any

female who was known to h ave entered it. To save her character, she

married, him, but is said to have been treated by him with so much

barbarity as to be obliged to leave his house, when he was forced to

allow her a separate maintenance. Of the eldest son, General Simon

Fraser, born 19th October, 1726, an account has been already

given. The second son, Alexander, born in 1729, after serving in the

army abroad, returned to the Highlands with the title of brigadier.

Janet, the elder daughter, married Macpherson of Clunie. Sybilla, the

younger, died unmarried. On the faith of his ‘Memoirs written by himself

in the French language,’ Lord Lovat has been admitted into Walpole’s

list of Royal and Noble Authors. The subjoined woodcut is taken from his

well-known portrait by Hogarth:

[portrait of Lord Lovat]

FRASER, ROBERT, F.R.S.,

an eminent statistical writer, eldest son of the Rev. George Fraser,

minister, first of Redgorton, and afterwards of Monedie, Perthshire, a

lineal descendant of one of the Frasers of Farraline in Stratherrick,

was born in the manse of Redgorton, about 1760. At an early age he was

sent, with his cousin, the celebrated antiquarian, Thomas Thomson, Esq.,

of the General Register House, Edinburgh, to the university of Glasgow,

and placed under the care of their uncle, Professor Traill of that

college. Here he became remarkable for the accuracy and extent of his

scholarship, and was admitted to the degree of master of arts before he

was fifteen years of age. He studied for the Church of Scotland, but on

leaving college he went as a tutor to a family in the Isle of Man, and

afterwards proceeded to London, where he attracted the notice of Mr.

Pitt, then prime minister, and was employed by the government in various

statistical inquiries regarding the Isle of Man, and the counties of

Devon and Cornwall. He subsequently obtained an official appointment in

the establishment of the prince of Wales (afterwards George the Fourth).

As he had shown considerable zeal and ability in his endeavours to

increase the resources of the country, by improvements in the fisheries

and mining interests of Great Britain and Ireland, he was applied to, in

1791, by the earl of Breadalbane, to accompany him on a tour through the

Western Isles and Highlands of Scotland, with a view to the discovery of

the best means of promoting the welfare of the inhabitants. On making

application for leave to the prince of Wales, he received from his royal

highness a note, of which the following is an extract: “Whatever neglect

may happen in the department intrusted to you in my affairs, I think it

is of so much consequence to the improvement of those counties that the

earl of Breadalbane should interest himself about them, that you have

not only my leave, but my best wishes for your success, and if on your

return you have anything you would wish to report, I myself will take it

to the king, as I know there is nothing nearer his majesty’s heart than

the desire of promoting the happiness and prosperity of those parts of

the kingdom.”

Mr. Fraser was subsequently chosen by the government to carry out a

series of statistical surveys in Ireland, and he was the means of

originating several important works in that country, among others the

celebrated harbour of Kingstown, (sometimes called Queenstown,) in the

neighbourhood of Dublin. He died in 1831. His eldest son, the Rev.

Robert William Fraser, M.A., became, in 1844, minister of the parish of

St. John’s, Edinburgh. His next brother, Major William Fraser, Hon. East

India Company’s service, founded the celebrated stud of the Company at

Pusa, of which he was appointed superintendent. He was on the staff of

Sir David Baird at the storming of Seringapatam, and translated from the

Persian, a valuable work on horsemanship, which was printed at Calcutta

in 1802, 4to.

Mr. Fraser’s works are:

Statistical Account of the County of Wexford, 8vo.

General View of the Agriculture and Mineralogy of the County of Wicklow,

Dublin, 1801, 8vo.

Gleanings in Ireland; particularly respecting its Agriculture, Mines,

and Fisheries. London, 1802, 8vo.

Letter to the Right Hon. Charles Abbot, Speaker of the House of Commons,

on the most effectual Means for the Improvement of the Coasts and

Western Islands of Scotland, and the extension of the Fisheries. London,

1803, 8vo.

The Statistical Account of the Counties of Devon and Cornwall, drawn up

and printed by order of the House of Commons. London, 1804, 4to.

Review of the Domestic Fisheries of Great Britain and Ireland.

Edinburgh, 1818, 4to.

FRASER, ROBERT,

an ingenious poet, remarkable also for his facility in the acquisition

of languages, the son of a sea-faring man, was born June 24, 1798, in

the village of Pathhead, parish of Dysart, Fifeshire. In the summer of

1802 he was sent to a school in his native village, and after being

eighteen months there, and about four years at another school, he went

to the town’s school of Pathhead, and early in 1809 commenced the study

of the Latin language. In 1812 he was apprenticed to a wine and spirit

merchant in Kirkcaldy, with whom he remained four years. In the summer

of 1813 he was afflicted with an abscess in his right arm, which

confined him to the house for several months, during which time he

studied the Latin language more closely than ever, and afterwards added

the Greek, French, and Italian; and acquired a thorough knowledge of

general literature.

In 1817, on the expiry of his apprenticeship, he became clerk or

book-keeper to a respectable ironmonger in Kirkcaldy, and in the spring

of 1819 he commenced business as an ironmonger in that town, in

partnership with Mr. James Robertson. In March 1820 he married Miss Ann

Cumming, who, with eight children, survived him. His leisure time was

invariably devoted to the acquisition of knowledge; and in September

1825 he commenced the study of the German language. About this period

his shop was broken into during the night, and jewellery to the value of

£200 stolen from it, of which, or of the robbers, no trace was ever

discovered.

Having made himself master not only of the German but of the Spanish

languages, he translated from both various pieces of poetry, which, as

well as some original productions of his, evincing much simplicity,

grace, and tenderness, appeared in the Edinburgh Literary Gazette, the

Edinburgh Literary Journal, and various of the newspapers of the period.

In August 1833 his copartnership with Mr. Robertson was dissolved, and

he commenced business on his own account. Owing, however, to the sudden

death, in 1836, of a friend in whose pecuniary affairs he was deeply

involved, and the decline of this own health, his business,

notwithstanding his well-known steadiness, industry, and application,

did not prosper, and, in 1837, he was under the necessity of compounding

with his creditors. It is much to his credit that several respectable

merchants of his native town offered to become security for the

composition.

In March 1838, he was appointed editor of the Fife Herald, and on

leaving Kircaldy he was, on August 31st of that year,

entertained at a public dinner by a numerous party of his townsmen, when

he was presented with a copy of the Encyclopedia Britannica, seventh

edition, as a testimonial of respect for his talents and private

character. Declining health prevented him from long exercising the

functions of an editor, and on being at last confined to bed, the duties

were performed for him by a friend. In the intervals of acute pain he

employed himself in arranging his poems with a view to publication; and

among the last acts of his life was the dictation of some Norwegian or

Danish translations. He died May 22, 1839. His ‘Poetical Remains,’ with

a well written and discriminating memoir of the author by Mr. David

Vedder, was published soon after his death.