|

The stranger in Edinburgh, perchance on some dull

grey day when the bitter East pours its misty breath over the

already dark wynds and closes of the ancient Scottish capital, may

be pardoned, as he trudges down the old High Street, for casting

merely a passing glance at the modern, japanned tinplate bearing the

apparently totally uninteresting words, 'Niddry Street.’ He would

not by any means be so readily pardoned if he still showed

indifference when we told him that in a hall still existing at the

foot of that street there used to regularly assemble, in the days of

long ago, a brilliant company of high-born dames and the leading men

of the period, to listen to concerts of classical and national music

rendered by an orchestra, professional and amateur, the most eminent

that the time could produce. The very walls still stand that

vibrated to the strains of the Messiak as a new oratorio, that

echoed to the tenor of Tenducci and the falsetto of Corri; in this

very hall an old gentleman was overheard to say, on hearing for the

first time a sonata of Haydn’s, ‘Poor new-fangled stuff! —I hope we

shall never hear it again’; that very cupola looked down upon the

flirtations of the beautiful Eglantine Maxwell, saw behind the

facile fan of Jane, Duchess of Gordon, and watched the rhythm of the

melody flush the damask cheek of the heavenly Miss Burnet with a

matchlessly delicate hue.

It seems a ‘far cry’ from the once narrow, tortuous,

sunless alley of the Middry Wynd, with its tall, age-stained ‘lands’

shutting out the daylight of the cold northern sky, to the bright,

sun-bathed Italian city of Parma, lit by the smiles of an eternal

blue; and yet there is one link of direct association, for the

architect of St. Cecilia’s Hall built it on the model of the

opera-house of Parma. The Teatro Farnese of Parma, long very

ruinous, was a wooden structure erected in the years r6i8 and 1619

from the designs of Aleotti d’Argenta. It held 4500 persons. The

Edinburgh of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries

was by no means that isolated, out-of the-world place which some

suppose it: its younger sons had for generations supplied soldiers

for a Royal Guard at the court of France; its best-loved, girl widow

queen had come straight from Paris to the Port of Leith; that

queen’s father had been married in Notre-Dame; that queen’s son

brought his bride by sea from Denmark; the battlefields of Sweden

and Holland knew the Scottish veterans almost better than did their

patrimonial castles; the Guises were as familiar with Edinburgh as

with their duchy; the greatest Scottish reformer knew Geneva and

Frankfort as well as he knew St. Andrews and the Netherbow; and the

most familiar cry in the streets ot Edinburgh was a corruption of a

French phrase. .

The Old Edinburgh of to-day, with sombre grey

sandstone and absence of bright colour alike on its houses and its

inhabitants, presents a very different appearance artistically from

that of mediaeval Edinburgh, which, if indeed its sky was so often

as leaden as ours—a thing to be seriously doubted,—was a city of

brilliant colouring on roofs, balconies, timber-fronts, pillars,

piazzas, and outside stairs; while its frequent royal, ecclesiastic,

and civic processions would ever and anon fill its crowded streets

with new elements of chromatism.

To all this, add the gaily coloured dress of peers

and peasants, burghers and country visitors, and you have a scene

fall of all possible colour-combinations, some of which no doubt

would have scandalised the modern aesthete; for as the sounds of

drawn swords would have clashed in his ears, so would colours in his

eyes, on the venerable High Street. A modern might doubtless find

that colours ‘killed’ each other in those days as readily as men

did.

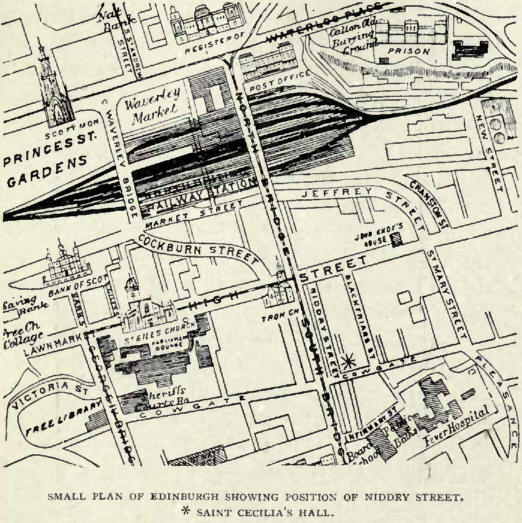

Niddry Street is the first on the right-hand side as

you descend the High Street from where ‘The Bridges’ cross it at the

Tron Church, and has been known as a street since about 1788, when

the wynd of mediaeval times was entirely swept away during the

formation of that great piece of engineerng, the South Bridge.

A large number of vary old, and no doubt very

insanitary, but at the same time historical and picturesque,

mansions were pulled down to make way for monotonous and commonplace

blorks of houses. The wynd had been, in a Pickwickian sense,

‘improved,’ but improved off the face of the earth. Into the vexed

question of how far, in a city like Edinburgh, we are warranted in

listening to the claims of Hygiene while remaining deaf to those of

History, ^Estheticism, and Archaeology, we must not at present

enter: suffice it to say that, for the last thirty years, ‘Ichabod’

may be said to have been ‘ writ large ’ upon the sky of the Niddry

Wynd. Although we may discover many a more romantic and historical

locality in Old Edinburgh, Niddry Wynd has had its full share of

both romance and history.

First as to the name itself: there can be little

doubt that the ground on which the wynd came to be buiit was the

intramural possession of some landed proprietor of the name of

Niddry. In charters of David II. a Henry Niddry is mentioned, and in

those of Robert III. a John Niddry is found owning land both at

Cramond and at Pentland Muir. The Wauchopes of Niddry in Midlothian

— the oldest family in the county, having come to Scotland in the

eleventh century with Margaret, queen of Malcolm Canmore—have

evidently existed long enough to have had a town-house in this wynd

so named from the circumstance—a very common source of the names of

old Edinburgh closes, e.g. Strichen’s from the Frasers of Strichen,

Tweeddale Court from the Hays of Tweed-dale, Libcrton’s from the

Littles of Liberton, Warris-ton’s from the lairds of Warriston, and

so on. In the reign of James III., Niddry Wynd was where the Salt

Market was held.

The most notable family whose mansion stood in the

wynd itself was that of Lockhart of Carnwath, the head of which at

the time of the Union was George Lockhart (born 1673, died 1731),

who figured very prominently in those stirring days, being one of

four representatives for the county of Edinburgh ;n the last

Scottish Parliament. Their mansion was built in 1591 by a Nicol

Edward or Udward, round four sides of a court (later known as

Lockhart Court) on the west side of the wjnd about half-way down. It

was demolished in 1785 to allow of the construction of the South

Bridge, the new southern approach to the city. According to the late

Sir Daniel Wilson, this house seems to have been one of the most

magnificent residences of the old town, which is sajing a good deal,

for at this date almost every wynd had in it one or more houses very

richly decorated. The Lockharts of Oarnwdth must be distinguished

from the Lockharts of Lee, whose mansion was in Old Bank Close. In

what was later the Lockhart mansion, James vi. and Anne of Denmark

were entertained, at their own request, in January 1591 by Nicol

Edward. King James was often the self-invited guest of his wealthy

subjects, and had been indeed entertained in another house in this

same wynd in 1584 by Provost Black of Balbi. This latter place was

nearer the 1 heid o’ the wynd,’ and it was from here that the King

walked in state to hold a Parliament in the Old Tolbooth. From the

Lockhart mansion it was that the Earl of Huntly, on February 7,

1593, fled to a deed of blood—the murder of the ‘Bonny Earl of

Moray’ at Donibristle, while at a much later date there lived here

Bruce of Kinnaird, the famous traveller to the sources of the Nile

(1770).

The old Niddry Wynd was likewise the home in the

metropolis of another Scottish family, the mention of whose name

recalls a tale of violence and mystery— the Erskines of Grange.

Their mansion stood on the other side, almost opposite Lockhart

Court. The story is a well-known one in Edinburgh annals under the

title ‘ Banishment of Lady Grange ’; but the lady in question had in

reality no title, being the wife of the Hon. James Erskine, a Lord

of Session with the judicial or territorial title of Lord Grange.

James V., who instituted the College of Justice, while admitting

that he had ‘made the carls Lords,’ once asked, ‘Wha the deil made

the carlines Ladies?’ We have thus the matter of titles of the wives

of Lords of Session settled by one who was perhaps the chief

lady’s-man in a dynasty which cannot be truthfully reproached with

lack of gallantry.

Told as briefly as possible, the story is that Lord

Grange, after thirty years of wedded life, banished his wife to the

remote island of St. Kilda, where he kept her a prisoner for seven

years. It seems pretty clearly proved that the lady was carried off

with considerable violence from her house in the Niddry Wynd by

certain persons in the service of Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, a man

whose own record in matters matrimonial was highly discreditable.

Lord Grange talked of the affair as a ‘

sequestration,’ under which guise it almost appears as though he had

done something heroic; but the fact that a Lord of Session so lately

as 1732 could with impunity banish his wife, without even the

semblance of a trial, to a lonely ;sland, is not only a curious

commentary upon the temper and manners of legal luminaries of that

period, but is a striking indication of the hypnotic state of public

opinion.

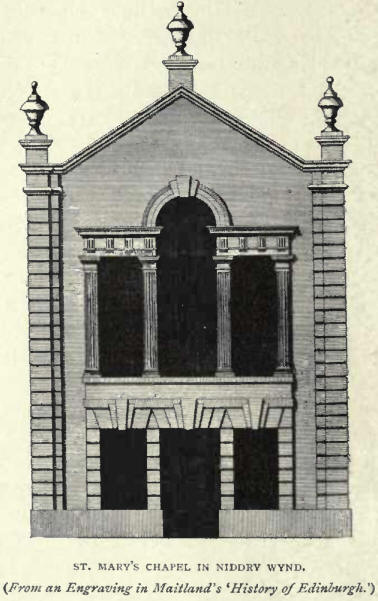

The ecclesiastical antiquities of the wynd are not

without interest. At the time Arnot wrote his History (1779) there

still stood, a little below Lockhart Court and on the opposite side,

an ancient chapel—St. Mary’s—dedicated to God and the Blessed

Virgin, and built in 1505 by ‘Elizabeth, Countess of Ross.’ In 1618

the Corporation of Wrights and Masons purchased it, and for long

used it as their place of meeting. Later they came to be known as

the ‘ United Incorporations of Mary’s Chapel,’ and in Arnot’s time

were meeting in the old place. Not long afterwards a new chapel was

built, and was the scene of certain religious services in 1770

promoted by the zealous Lady Glenorchy. In 1779 the Rev. John Logan

of South Leith, a poet of some repute in his day, gave a course of

lectures in the chapel upon the ‘Philosophy of History,’ prior to

offering himself as a candidate for the Chair of Civil History in

the University of Edinburgh.

Even in the days of the original chapel, the

Freemasons had met in it, and there has for long existed ‘a masonic

lodge of Mary’s Chapel.’ There met the Musical Society, which was

not only the direct predecessor but the parent of the St. Cecilia’s

Society, for whom the hall was built at the foot of the wynd. We

shall have a good deal to say of this Society when tracing the

development of the Concert in Edinburgh.

The Niddry Wynd is always mentioned in connection

with Allan Ramsay’s first Edinburgh house and shop at the sign of

the Mercury opposite the head of the Niddry Wynd. Prior to 1725 he

here conducted his business; and it was here that he published

the Gentle Shepherd—a work of which it has been well said, It has

only just escaped being a classic.’

Again the Niddry Wynd figures in the short, sad life

of Edinburgh’s youthful poet, Robert Fergusson, better known,

unfortunately, as Burns’s model for metre than for anything he

himself wrote. This Fergusson was born (5th September 1750) in the

‘Cap and Feather Close ’in a high land ’on the east side of

Halkerston’s Wynd, and was sent in 1756 naturally to the nearest

school. This happened to be one somewhere in the Niddry Wynd, opened

in 1750 by a Mr. Philp—‘Teacher of English.’

The Niddry Wynd comes up in connection with the town

house of the noted Edinburgh surgeon, Benjamin Bell—one of the early

luminaries who contributed to give the Edinburgh school of Medicine

that prestige which to this day it has never lost. Writing in

September 1777, he tells how he had ‘got fixed at last in a very

good house, weil aired and lighted, with an easy access of one story

from Niddry’s Wynd, and an entry from Kinloch’s Close without any

stairs.’ This Benjanvn Bell was the great-grandfather of the

well-known and no less well-beloved Edinburgh surgeon of the present

day, Dr. Joseph Bell, whose remarkable intuitions with regard to his

patients suggested to his pupil Conan Doyle the character which he

afterwards amplified as ‘Sherlock Holmes.’ St. Cecilia’s Hall

extended from the Niddry Wynd on the west through to Dickson’s Close

on the east, both the wynd and the close running between the High

Street and the Cowgate. Kinloch’s Close, which also descended from

the High Street towards the Cowgate, did not extend further than the

north elevation of St. Mary’s Chapel, and was thus not a

thoroughfare. |