|

MAKING A PREMIER

Quite a settlement had

been formed along the Penetang' Road north of Barrie ten years before

settlement began even at the southern end of Innisfil, the township

forming the west shore of the lower end of Lake Simcoe. There were two

reasons for this. The first was due to comparative ease of

communication; the second, to market facilities. The old military

highway between Lake Ontario and Georgian Bay followed the line of Yonge

Street to Holland Landing, thence up Lake Simcoe to Kempenfeldt Bay and

then again overland to Penetanguishene. Hence it was a comparatively

easy matter to reach the country about Crown Hill, Dalston, and

Craighurst several years before the opening of the lower section of the

Penetang' Road between Holland Landing and Barrie provided for the

settlement of Innisfil.

The principal reason for

the earlier settlement in the more northerly section was based on market

considerations. The naval and military post, first established at

Nottawasaga, was transferred from that point to Penetanguishene in 1818

and somewhat later the post at Drummond Island was added. The presence

of a military and naval station thus made this northern port a centre of

commercial activity. It was a centre of Indian trade as well, "and there

was," as a grandson of one of the Crown Hill pioneers expressed it, "a

general belief that Penetang' was destined to be the metropolis of Upper

Canada."

The Penetang' dream of

the pioneers has not come true, but Crown Hill, which owes its origin to

the existence of the old naval station on Georgian Bay, has to its

credit something that cannot be claimed for any other rural section of

Ontario. It gave to the province the first head of the provincial

Department of Agriculture and in the son of that head the first farmer

premier of the province. The Drurys, Partridges, and Hicklings were

among the first to come in along the upper end of the Penetang' Road,

settling in 1819 near where Crown Hill now is; the Lucks, another large

connection, corning in a year later. The Drurys came from England; the

Lucks and Partridges, from Albany, N.Y.

"When Grandfather

Partridge moved in, lie brought his wife and two children with him as

far as Holland Landing," one of the third generation told me. "From

Holland Landing he walked alone all the way to Penetang,' his route

around the west side of Lake Simcoe to Kempenfeldt Bay being over a

blazed trail. After satisfying himself as to the future of Penetang' he

started to walk back, digging into the soil at intervals by the way in

order to learn its quality. He walked twenty-five miles before finding

what suited him, and finally located near Crown Hill, taking up four

hundred acres in all, half on the Oro and half on the Vespra side.

Having built a log cabin he went back to Holland Landing for his wife

and children and began family life in the new home in the bush in

October. Afterwards, when the road was fully opened out, lie found that

his cabin was almost in the middle of the King's highway. Hardships m

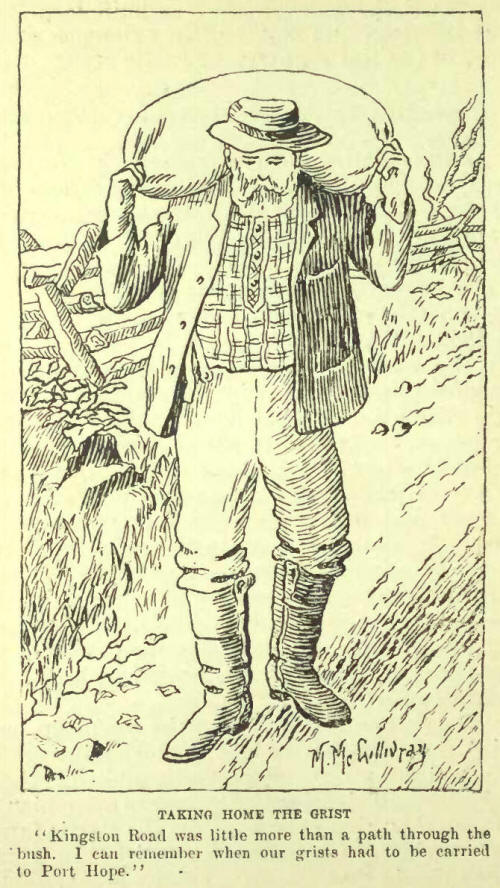

You can judge of general conditions at that time when I relate one fact

told me by my grandfather. He packed his first grist on his back from

Crown Hill to the east end of what is now Barrie and then paddled it in

a dugout the rest of the way, twenty miles, to the old Red Mill at

Holland .Landing."

One hundred years ago

Penetang' Road was an Indian highway, as well as a military road, the

Indians traversing it on their way to Toronto for the annual

distribution of presents by the Government. On one occasion, as narrated

by Hunter in his "History of Simcoe County," a number of drunken red men

called at the home of James White, while his wife was alone in the

house, and were promptly chased out again by Mrs. White, who had armed

herself with a pair of tongs.

Adventures with bears

there were, too, one of these being narrated by Hunter. Gideon

Richardson, to protect his pigs against the black marauders, built a pen

opposite the door of his cabin and kept a log fire burning at night

beyond the pen. One night, after a rain, the fire could not be lighted

and bruin took advantage of the situation to raid the pen. In the course

of the attack one pig was hurled through the door of the cabin into the

midst of the sleeping inmates. There was no more sleep for the family

that night.

One of the first cares of

the settlement about Crown Hill was to make provision for the

educ'a.tion of the children, and some time before 1837 a voluntary

school was established, with William Crae as the first teacher. Crown

Hill pioneers were also among the first to take advantage of the

Education Acts of 1841-43, under which an annual provincial

appropriation of twenty thousand pounds was made to assist in the work

of primary education. In fact, a school was established on the Vespra

side as early as 1842 with Edward Luck as the first teacher, a position

he filled for twenty-two years. The selection of Mr. Luck was peculiarly

fitting in at least one respect as, from first to last, no fewer than

fifteen of his own children passed under the rod in that same school.

"The building was, of

course, of log," said i grandson of one of the pioneers, "and the

benches were of plank with home-made legs supporting them. In the

beginning the building was used for a church as well as a school, and

there was a pulpit in one corner for the church services. Pastor Ardagh

and Canon Morgan were the first to officiate. Marriage services were

performed there, and on such occasions the benches were moved back and

boys and girls lined up in front of the pulpit as witnesses."

The old minute book of

the section, dating back to 1844, is still in existence. This records

that Thomas Ambler, George Caldwell, and Jonathan Sissons, the latter

grandfather of Professor Sissons of Victoria College, were the trustees

in 1845. The record further shows that the salary paid Mr. Luck in that

year was twenty-five pounds currency "over and above Government

allowance and taxes." In order to make tip the amount required to keep

the school going, sixteen of the settlers agreed to pay one pound for

each child sent to school by them, the largest single contributor being

William Larkin, who paid four pounds. Among the other contributors were

Jonathan Sissons, Thomas Mairs (one of the first. importers of "Durham"

cattle), Charles Partridge, Charles Hickling, Thomas Drury, and Richard

Drury, the latter being the grandfather of Premier E. C. Drury.

The amounts contributed

by these enlightened pioneers for the education of their children may

seem small to those of the present generation, but they were in reality

relatively larger than similar contributions to-day. Incomes were small.

By that time local production had exceeded the requirements of the local

market at Penetang' and an outlet had to be found at Toronto, seventy

miles away over rough roads. The prices obtained for farm produce in

general at the provincial capital may be gauged by the fact that oats

teamed there, reaped with a cradle and threshed with a flail, sold for

twenty-five cents per bushel.

Among the first purchases

in the way of supplies for the new school, as an ancient record further

informs us, were "two grammars, costing four shillings, two and one-half

pence" and "three dictionaries costing five shillings, seven and

one-half pence." In 1852, eleven families raised sixteen pounds, fifteen

shillings and nine-pence for the school, the largest contributor in that

year being Richard Drury, who gave two pounds, nineteen shillings and

three-pence. At the annual school meeting held on January 31st, 1853,

with Jonathan Sissons in the chair, it was decided, on motion of G.

Hickling and E. Luck, that there "shall be a free school." This

resolution does not seem to have gone into effect at once as nine of

those present voluntarily bound themselves to "raise any amount needed

in excess of the legislative grant and municipal levy. Among the nine

guarantors were J. Sissons, Charles Hickling, Charles Partridge, 'Thomas

Drury, and Richard Drury. In 1855, a further forward step was taken when

the trustees were empowered to buy maps of the world and of America as

well as books to be distributed as prizes at the next examination of

pupils.

I remember once hearing

one of the faculty of Cornell University say that lie could have made a

much better man of a certain student had lie been given the selection of

that individual's grandparents. The present Premier of Ontario was

fortunate in the selection of his ancestors. In the arduous work of the

pioneer days his grandfather and great-grandfather had their full share.

in the midst of blackened stumps, and with the primeval forest still

unconquered, as the old school record quoted from shows, they bore the

heavy end of the burden in providing for the education of the children

of the pioneer settlement. In establishing municipal government the

Drury family also took part ; Thomas Drury having been a member of one

of the early councils of Oro, while Richard Drury served as Reeve on

different occasions, and Charles Drury, father of the Premier, beginning

as reeve of Oro ended his political career as Minister of Agriculture

for the province. It is not by one of fortune's freaks that E. C. Drury

to-day holds the position of first citizen of the wealthiest and most

populous province of Canada.

VILLAGES THAT ARE NO MORE

Few men had a wider or

more varied knowledge of early days in Simcoe County than William Hewson,

who told me his story in Barrie in the summer of 1900. Mr. Hewson had

seen Canadian voyageurs on their way to Montreal with pelts, when Lake

Simcoe was a link in one of the chief highways between the Upper Lakes

and the Gulf; he had seen the annual movement of Indians back and forth

between Toronto and Georgian Bay; his father's home was one of the

halting points for British soldiers on their way to and from Penetang',

and he was eye-witness of the beginning of the white migration to the

country surrounding the lake which bears the name of Upper. Canada's

first governor.

Mr. Hewson was located at

a particularly favourable place for viewing these movements, having

settled with his father on Big Bay Point in 1820. From that date until

after the last century ended he lived almost continuously in Simcoe

County.

"When I was a lad," said

Mr. Hewson, "one of the great receiving depots in the days of the fur

trade was maintained by Alfred Thompson, of Penetang'. Mr. Thompson's

winter receipts of pelts had an aggregate value of from thirty thousand

to forty thousand dollars. When ready to sell he advertised in England

and Germany, 'and representatives of European firms came out to submit

tenders, the highest being accepted. Our home at `The Point' was on the

highway connecting Toronto and Georgian Bay. Past our door Canadian

voyageurs, employed by a Montreal firm, paddled their canoes loaded to

the limit with rich furs taken in the hunting grounds of the great north

country. It was a day's journey by canoe from Lake Couchiching to 'The

Point,' and when the Indians were on their return journey from Toronto

after receiving their annuity money, I have seen seven hundred camped on

our farm at one time. Soldiers on their way to and from the fort at

Penetang' also made our home a resting place. Later on, when the tide of

white immigration began to flow into the country about Lake Simcoe a

good deal of that tide swept around our farm. At that time two or three

bateaux, carrying settlers and their effects, made regular trips between

Holland Landing and Barrie, and we could see these as they rounded `The

Point'.

"The most picturesque

scenes and exciting times were furnished by the Indians. In summer the

clothing of the men was limited to breech cloths and that of the women

to petticoats, the body being left bare from the waist up. On the whole

journey from Toronto northward rascally traders plied the Indians with

whiskey, obtaining in exchange the guns, blankets, and tomahawks which

the Indians had received from the Government. By the time Big Bay Point

was reached the Indians, soaked with whiskey, were ready to quarrel on

slight provocation. When a general scrimmage began, the squaws grabbed

the papooses and ran for the bush. Strange to say, all this fighting was

done with fists; I never once saw guns or knives used. The Indians were

usually chaste in their domestic relations, but one old chief, John

Essence, had three wives. When converted to Methodism he was told he

would have to put away two of these, and the old polygamist sought a way

out. On being told that he could retain all three wives if he became a

Catholic, he promptly abjured Methodism for what seemed to him a more

liberal faith."

This talk led up to tales

of early marriages among the whites. Mr. Hewson's father was a

magistrate and as such was authorized to perform the marriage ceremony.

His field covered the whole country from Holland Landing to Penetang.

"One of the first marriage ceremonies performed by my father was when he

declared his neighbour David Soules legally wedded. Soules had gone to

Pickering for his bride, a Miss Yeomans, and the trip across Lake Simcoe

was made in a boat rowed by the prospective groom.

"The law required the posting of notices of intention to marry in three

prominent places for three weeks before marriage. A widower, a Quaker

about to remarry, put up one of his notices in the cleft of a tree,

hoping thereby to comply with the law while at the same time avoiding

publicity. It happened, however, that a search party, while hunting for

a man who had been lost in the bush, came across this notice and soon

made it public enough to comply with the most rigid of legal

requirements. One day, when father was away from home, a negro came to

our place to be married. When this man found father was away he wanted

my mother to act, on the ground that the Bible pronounced man and wife

one. He contended, therefore, that what one could do the other could

surely do as well. However, the colored man was told he would not only

have to wait until father returned but until notice could be given also.

Three weeks later, after legal notice had been given, when father went

to perform the ceremony, he found the couple already living together as

man and wife. One couple, far from either minister or magistrate, did

not have the ceremony performed in their case until one of their sons

was grown up.

"The first Methodist

minister in Innisfil township was Hardy by name, and he was hardy by

nature. His field was from 'Penetang' to 'The Landing'; he covered that

distance twice a week on foot and held nine services in the seven days.

"There were few better stands of pine in Ontario than that of Innisfil

when the first settlers came in. Near the site of the Twelfth Line

Church a man named Pratt had a particularly good lot of pine trees and

lie offered these, as they stood, at one cent per log to Robert

Thompson, who then had a mill at Painswick. But pine was worth so little

at the time that the offer was refused. When the old Northern Railway

was built, pine did begin to have a value, and quite an active lumbering

industry sprang

up in the township. Sage

and Grant, who introduced bob-sleighs into Innisfil, had a mill at Belle

Ewart that at one time employed seventy men. Mills were also established

at `The Point', Tollendale, Craigvale, the Seventh Line, Gilford and

Lakeland. At Lakeland, iii addition to the mill, there was at dock,

hotel, store, and a really attractive group of homes with locusts

ornamenting the front yards."

But all these mills have

disappeared long since. and Lakel<aiid and Belle Ewart, would be mere

sand beaches to-day had it not been for the development of the Lake

Simcoe ice trade in winter and tourist traffic in summer.

At the time that Mr.

Hewson related to me his stories of the days when Lake Simcoe was an

important link in a great highway between north and south I obtained

from Dr. B. Paterson, then of Barrie, some further particulars regarding

the beginning of the Toronto Penetang route. According to Dr. Paterson

the journey between these two places was at times made by an entirely

overland route as early as 1814.

"At that time," Dr.

Paterson said, "my father had a contract for transporting supplies from

Toronto for the garrison of two hundred men at Penetang'. The entire

journey was made by an overland route, passing to the westward of the

bay at Barrie. Over part of that route, however, axes had to be carried

to cut trees out of the way, and the trip occupied two weeks. Holland

River was crossed on a floating bridge, and frequently, on returning to

the river, it would be found that the bridge had been carried away, and

it was then necessary to build a new one. The only house between

Penetang' and 'The Landing' at that time was a hewed log affair at Crown

Hill.'

By Andrew Wallace, one of

the pioneers of Innisfil, I was given some further particulars about.

the Lakeland milling enterprise. "A man named Vance invested thirty

thousand dollars in that venture," Mr. Wallace said. "The mill did not

run very long and some years later, when the property had fallen into

decay, Vance visited the scene of desolation. As he was standing on the

wreck of the wharf looking into the water below some one asked him what

was interesting him. "I am trying to discover where my thirty thousand

dollars went," was the reply.

RAFTING TIMBER ON THE ST.

LAWRENCE

The family history of Mr.

Henry Smith of Barrie, another descendant of the Simcoe pioneers, is

remarkable for its variety of colour. The name was originally Schmidt,

and the first of the name in America was Heinrich Schmidt, an officer in

the Hessian troops sent over by George III at the time of the American

Revolutionary War. This Heinrich was the grandfather of Henry Smith,

whose story follows:

"The troop-ship, on which

my grandfather sailed to America, was eighteen weeks in crossing from

Germany," said Mr. Smith. "So long was the voyage, that the officer in

command of the troops asked the admiral of the fleet if he was quite

sure that he had not passed America in the night. When my maternal

grandmother, who was also with the troops, caught sight of a field of

corn after landing, she exclaimed: `America must, indeed, be a rich

country when there are so many ribbons here.' She mistook the leaves of

the ripening corn, glistening in the evening sun. for ribbons hung out

to dry.

"After the Revolution my

grandfather received a grant of land in the township of Marysburg,

Prince Edward County, and that is how Smith's Bay obtained its name. A

man called Snider, who had a rather notable nose, settled on a prominent

point in the same township and hence the name, locally applied, of

Snider's Nose."

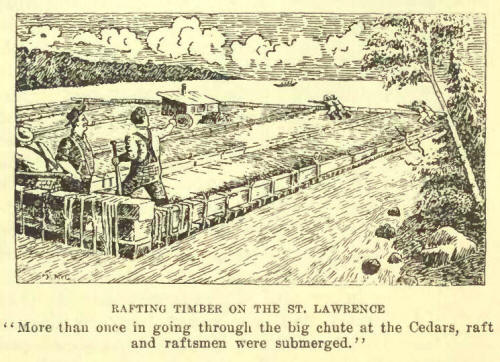

Mr. Smith's own life was

about as varied and full of adventure as that of his grandfather. As a

lad of fourteen he assisted in rafting timber down the St. Lawrence.

"More than once, in going through the big chute at the

Cedars, raft and raftsmen

were submerged in the waves, and it was then a case of sit tight or stay

under," said Mr. Smith. "Some of the timber forming the rafts came from

Prince Edward County, but more of it came down the Trent. Oak and pine

logs were rafted together, the latter helping to keep the former afloat.

A good deal of the timber was for spars. You can judge the length of

some of this spar timber, when I tell you that I have seen five, six,

and even seven saw-logs cut from one tree. The record spar, which was

one hundred and twenty feet long, came from Big Bay Point on Lake Simcoe.

Eight or ten teams were used in hauling such timbers from the bush to

the water's edge. When the rafts arrived at Montreal they were broken up

and loaded into sailing vessels for shipment to England. Those timber

vessels had large port-holes in their bows, and the timber was hauled to

these holes by horses operating a windlass and then shot into the hold.

When the timber fleet was in Montreal harbour the masts appeared like a

great forest from which the limbs had been stripped. As I went down the

river on rafts I often met immigrants coming up in bateaux or Durham

boats. These vessels were much alike save that the bateaux were open

while the Durhams were partially decked over. Men, women, and children

were huddled together in these craft by day and camped on shore at

night.

"All the lakes and rivers

were then full of fish. I helped haul in a net near Willard's Beach in

Prince Edward County that contained fourteen thousand fish, and I have

seen salmon near there that were eight inches through the body. In one

case a salmon actually broke the handle of the spear and got away, but

was afterwards caught with the fragment still in its body."

In 1847, Mr. Smith moved

to Vespra, north of Barrie. The journey from Toronto to Holland Landing

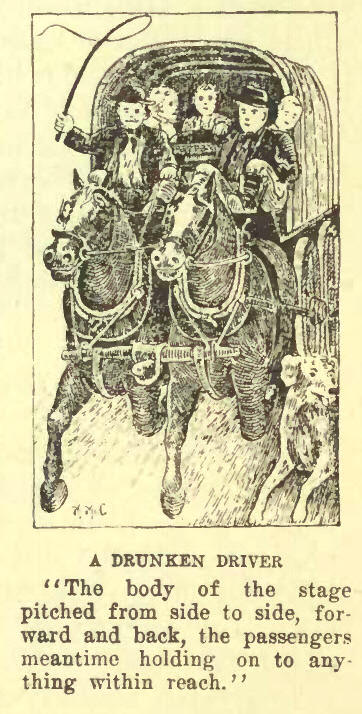

was by stage. "Near the end of the journey," said Mrs. Smith, "the

driver, who was drunk, lost control of the horses on the down grade of

one of the hills. The body of the stage pitched from side to side,

forward and back, the passengers meantime holding on to anything within

reach. It is a wonder our necks were not broken.

"From the `Landing' to

Barrie passage was taken by the steamer Beaver the remains of which are

now buried beneath the foundation of the local Grand Trunk Station. From

Barrie we followed the old Sunnidale or Nine Mile Portage Road to Willow

Creek."

I am indebted to Mr. A.

F. Hunter for the history of this old highway, which dates back to 1814,

and was built in the first place as a military highway. Early in the War

of 1812-15 a British force had captured the fort on Mackinac Island.

Later on the Americans prepared for its recapture. in order to reinforce

the Brit -ish garrison a force was despatched from Kingston in February,

1814. This force marched overland via Toronto to Holland Landing and

thence over the ice of Lake Simcoe to Barrie.

Front Barrie the Nine

Mile Portage Road was cut through to Willow Creek. There, trees, cut

from the surrounding forest, were fashioned into bateaux, and in these

improvised craft, when spring came, the relieving force floated down

Willow Creek to the Nottawasaga River, along that river to Georgian Bay,

and thence to Mackinac. Block-houses as bases of supply were built at

1-lolland Landing, Barrie, and Willow Creek; the Barrie block-house

being located where the music hall now stands. Willow Creek was quite an

important centre of settlement for years afterwards, but to-day not one

stone remains upon another. Only a few holes mark the site, these holes

having been dug in search of gold which tradition said had been buried

there.

A WAYSIDE INN'S FAMOUS

GUESTS

There is possibly no

other Ontario farm with the exception of farms along the lake frontier,

which is so prominently connected with local history as is the old

Warnica homestead,—lot thirteen on the twelfth of Innisfil,—opposite the

beautiful avenue of pines on the Penetang' Road, two miles south of

Barrie.

The farm was given to

John Stamm for his services with Button's Cavalry in the War of 1812-15,

and settlement duties on the place were begun by Stamm. Once, when on

his way to the place from Markham township, Stamm narrowly escaped

drowning in Lake Simcoe. That was enough of that location for him, and

he sold his place to the first of the Canadian Warnicas for ten dollars.

The Warnicas took possession in 1825. Shortly afterwards, because of the

growiug t raffle between north and south, the house on the place became

an mu; and, although there were only two rooms and a loft available for

travellers, some distinguished guests were entertained there. It is said

that Sir John Franklin spent a night at the inn on his overland trip to

the Arctic regions, and a voyageur sent back by Sir John sought shelter

at the same place on the return journey. Bishop Strachan, on journeys

north and south, made this a stopping place; and Sir John Colborne, when

Governor of Upper Canada, was provided with food and lodging there when

on his tour of inspection of the military post at Penetang'. So well

pleased was Sir John with the accommodation provided that he offered

each of the Warnica boys a free grant bush lot. How little such lots

were valued at the time is evidenced by the fact that the boys did not

think it worth while to go to Toronto to secure the deeds of the

property tendered them.

When the Warnicas first

settled in Innisfil, Lake Simcoe was still a connecting link on the

Toronto-Penetang' highway, and Big Bay point was located right on that

highway. David Soules, one of the first settlers on `The Point', told

Warnica he was a fool to settle so far to the west. "You will be away

off the main road," said Soules, "and the blackbirds will eat all your

crops." To-day, however, it is `The Point' that is isolated while the

old Warnica farm fronts on one of the principal provincial highways.

At the beginning the

Warnicas endured many privations. Clothing was largely made of homegrown

flax, and one of the IVarniea boys of that day had to stay in bed while

his one linen shirt was being washed.

The first grist from the

Warnica farm had to be hauled to the old "Red Mill" at Holland Landing.

Once when a grist was being taken it was intended to make the round trip

in a day, but the men were storm-stayed at Grassi Point on the return

journey. The night, however, was spent in comparative comfort, as

Indians who were camping there at the time supplied the Warnica boys

with blankets.

Running all through these

old-time sketches incidents are related in which the first settlers were

indebted to the Indians for kindness such as that shown the Warnicas.

The conduct of the aborigines stands all the more to their credit when

the manner in which they were being plundered and brutalized by white

traders is borne in mind.

Slowly but surely times

changed for the better. The settlement along the Penetang' Road north of

Barrie, producing beyond local needs, demanded a route all the way to

Toronto, and money was raised, apparently by public subscription, to

build around Barrie Bay a link to connect the old Penetang' Road north

of Barnie with the line north from Holland Landing. Two of the Warnica

boys were given the eon- tract of cutting out the bush from Tollendale

to Churchill, a distance of eleven miles, at five dollars per mile. That

would seem very small pay to road-builders of to-day, but five dollars

went a long way when Innisfil was young. The hardest part of the

Warnicas' task was at Stroud, which, although dry enough now, was a

difficult swamp at that time.

Previous to this the

Warnicas had made considerable money in teaming military supplies

intended for the Penetang' garrison over the Nine Mile Portage Road

between Barrie and Willow Creek. Then, when settlement began to move

into the Sunnidale and Beaver valleys, they obtained remunerative

employment in teaming the effects of the more northern settlers to their

destination.

The first of the Warnicas,

besides being a pioneer in the matter of settlement, was a participant

in the inauguration of municipal government in Innisfil. He, with

Charles Wilson and John Henry, formed the equivalent of the first local

council when Innisfil was municipally organized in 1841. He was also a

member of the Home District Council, which then met in Toronto. The

manner of election for it place in the latter body is an illustration of

the free and easy way in which elections were carried on in the early

days. Warnica and David Soules were contestants for the office and the

election was held at the old Myers tavern at Stroud. To decide the

matter it was arranged that one of the contestants should lead his

supporters south along the road from the tavern while the followers of

the other should be led north. The one that had the largest following,

and this was Warnica, was declared elected.

Some of the family

history of the Warnicas is as interesting as it that of the farm with

which the family name has been identified for a century. The first of

the family was a Dane, whose name was spelled Werneck. As a young man

Werneck possessed considerable means, which he spent largely in seeing

the world. On his return to Denmark, while telling of some of his

adventures, his word was questioned, whereupon Werneck promptly struck

down the

"Doubting Thomas." For

this he was fined forty kronen by a Danish magistrate. On paying the

fine Werneck asked if a second offence would cost the same, and was

assured it would. Another forty kronen pile was promptly counted out

with the first, and then Werneck knocked down the magistrate. At a much

later date, while playing the fiddle for a party in his Innisfil farm,

this fiery Dane had the misfortune to fall, and, when one of the party

asked if the fiddle had been broken, the fiddle was hurled at the head

of the questioner for making the first enquiry about the instrument

instead of for the life that might have been lost in the fall.

Some time after the forty

kronen incident Werneck sailed for New York, and there the family name

was changed to Warrick. On coming to Canada, at a still later date, the

"k" was changed to "a", and for three generations Warnica has been one

of the best known family names in the township of Innisfil.

While in New York State

Warnica married a German -widow named Myers. Mrs. Myers' parents, and

all of her grandparents with the exception of one grandmother, had been

killed and scalped during an Indian raid in the Mohawk Valley at the

time of the American Revolutionary War. The surviving grandmother had

been scalped and left for dead, but survived for years afterwards. Mrs.

Myers herself escaped the massacre because, as a babe, she was asleep

and was overlooked.

A combination of Danish

and German blood in the first of the family with subsequent

intermarriage amongst descendants of the English, Irish, and Scotch

pioneers of Innisfil, the Warnicas, like the old Hessian soldiers and

the descendants of the palatinates of Sunderland, furnish a striking

illustration of the varied nature of the strains entering into the

making of the Canadian commonwealth.

A. LONG WAY TO THE MILL

When I listened to the

story which follows, near the close of the last century, the country

between Barrie and Penetanguishene had long played its part in Canadian

history. Penetang' itself, like Toronto, figured in the War of 1812-15,

and the settlements between Barrie and Penetang' began almost as early

as settlements near Toronto. The Drury farm at Crown Hill, for example,

was taken up by the grandfather of the Honourable E. C. Drury in 1819,

and the Methodist Church at Dalston bears the dates 1827-97. At the same

time, not far from the road leading to Penetang,' pioneer conditions

still existed twenty-five years ago.

What is here related is

based mainly on what I was told by Thomas Craig, of Craighurst, who was

then living on the north half of lot forty-two on the first concession

of Medonte. Of that farm something could then be said that probably

could not be said of any other farm in Ontario. The lot was taken up a.s

a grant from the Crown by Mr. Craig's grandfather in 1821, and from that

time, until 1899, there was never a mortgage against the property, the

only records standing in connection therewith in the Registry Office at

Barrie being in the form of transfers from father to son.

"There were," said Mr.

Craig, "two reasons why grandfather located so far north. One was that.

the land about. Kernpenfeldt Bay was all in the hands of military

pensioners and that about Daiston in the hands of a company; the other

was that. the British garrison at Penetang' provided a convenient

market.

"Penetang' garrison was

maintained until about the middle of the century and was made up in part

of some of Wellington's veterans. One of these, Charles Collins, was in

the 52nd Regiment at Waterloo. John Hamilton was another Waterloo man.

Private McGinnis served in the Peninsular War and received his discharge

at Penetang.' He left a number of descendants in the country west of

Craighurst.

"As a boy," continued Mr.

Craig, "I saw parties of soldiers passing along the road on their way to

and from Penetang.' They travelled in small parties so as not to crowd

stopping places between Toronto and Georgian Bay. Once, when a party was

on the way north, the officer in charge swore that he would march his

men from Newmnarket to Penetang' in a. day. He did it, but two of the

men died by the wayside. One of these was literally done to death by

mosquitos and was buried near where Wye-bridge now stands.

"I have seen Indians,

hundreds and hundreds of them at a time, going along the same road on

their way to and from Toronto. In late fall they went south to make

baskets in the woods, then standing near Toronto, and to sell them in

the city. In early spring they returned to the Christian Islands to make

sugar, to fish, and later on to engage in the fall hunt. Although

drunkenness frequently occurred among the Indians, we did not fear them

as they never offered to molest the settlers."

Speaking of early,

experiences Mr. Craig went on: "Grists had to be carried all the way to

Newmarket, but the Government mill at Coldwater later on relieved us of

the necessity of snaking that journey. About 1830, Government and

settlers joined in erecting another mill at Tidhurst. For our groceries

we were still compelled to go to Newmarket, where the first of the

Cawthras then had a store. The road between here and Barrie was nothing

but a trail; from Barrie to Holland Landing we travelled on the ice in

winter and by boat in summer, and from Holland Landing to Newmarket by

Yonge Street. The round trip occupied three or four days. In the

beginning supplies were packed on the back, but later on two or three

joined in the use of an ox-team and jumper. Eventually F. C. Drury's

grandfather and my father ,joined in building a road around the bay at

Barrie, and then the entire journey could be made without crossing Lake

Simcoe.

"The first post-office

north of Newmarket was at Penetang'. There was a regular mail service

from Toronto to Newmarket, but mail for points further north was given

for delivery to the first reliable settler who happened to come along.

This volunteer carrier, the beginning of rural mail delivery,

distributed his letters as he passed up Yonge Street and time Penetang'

Road, and handed in the regular mail-bag for Penctang' when he reached

that point. Sometimes there were letters still in this bag for settlers

along the way, and these had to be sent back as chance offered."

The first wagon that

passed over this road was made in 1826 or 1827 by a man named White, of

Newmarket. It was built largely of Swedish iron and was still in

existence at the close of the last century.

HARDSHIPS OF THE

NOTTAWASAGA PIONEERS

As the country about

Creemore, in Nottawasaga, was settled at an earlier date than was Flos,

the hardships of the Nottawasaga pioneers were greater than those

sustained by the Flos pioneers.

One of the early settlers

in Nottawasaga was Joseph Galloway, who located near Creemore in 1852.

Some twenty years before that time, Mr. Galloway's father, who was then

living near Bradford, teamed flour into the northern township with oxen.

"That flour," said Mr. Joseph Galloway, "was sold to the settlers at

eight or ten dollars per barrel; but it was worth the cost as a week was

taken on the round trip, and over a great part of the way the country

was solid bush. Tt was dear flour to the settlers all the same, as some

of those who purchased it had earned the necessary money by working in

the harvest fields at `tile front' at fifty cents per day. Some were

unable to pay the price and, on one occasion, one mail weilt without

bread for nearly two weeks.

"Even when I moved into

the township one-third of the lots for the last fourteen miles of the

way had not a tree cut on them, and the others had but small clearings.

Deer were more plentifill then than sheep are now. On the Currie farm,

just outside of Creemore, were `licks' to which deer came in droves. In

a nearby creek, now a

mere dribble, one could

catch a pailful of speckled trout in an hour. In one night wolves killed

fourteen sheep.

"We had the choice of

four markets—Barrie, Bradford, Holland Landing, and Newmarket. To reach

Barrie, the nearest of the four, involved a journey covering two whole

days and part of the nights. Our usual practice was to leave before

three in the morning, and if we got back at midnight of the second day

we considered ourselves lucky. Twenty-five to thirty

bushels made a load of

wheat. The price was fifty cents per bushel, and half trade at that. A

yoke of oxen, weighing over a ton each, sold in Toronto for sixty-five

dollars. A change came with the extension of the old Northern Railway to

Collingwood and with the Crimean War. In the fall of 1854 I sold wheat

for fifty cents at Bradford; the next year I got one dollar and a half

at Stayner. "It was plain living in the early days. Our log house was

eighteen feet wide by twenty-four feet deep, and eleven logs high. There

was a stone fireplace and chimney at one end, and to reach the upper

rooms a ladder was used instead of stairs. Bread was baked in a pot that

would hold half a pail of dough and the baking was done by putting the

pot in a pail of ashes on the hearth. We had a frying-pan with a long

handle in which we cooked venison and trout, the pan being placed on the

coals in the fireplace. There were wild plum trees about a mile away,

and from these we gathered two or three pails in a season."

The parents of Archie

Currie, formerly M.P.P. for West Simcoe, were also among the early

settlers in Nottawasaga, coming there from Mariposa. In moving they

crossed Lake Simcoe on the ice, and proceeded thence by way of Orillia

and Barrie to the sixth of Nottawasaga. "The clearing on the place to

which we moved was barely large enough to enable us to see the blue sky

above," Mr. Currie's mother told me. "There was no floor in the house

when we arrived, only a few boards to set the stove on; and, the doors

not being in place, we hung blankets over the openings to keep out the

winter wind. What is now Creemore was a network of tangled trees."

It was the practice of

the first settlers to go in parties when teaming their produce to Barrie

with ox-teams. There were no taverns by the roadside, and at dinner or

supper time a halt was made at a clearing. While the oxen ate their hay,

the men smoked their pipes and gossiped, an occasional drink of whiskey

causing the gossip to flow more freely. Sometimes a party would be

storm-bound in Barrie, and in that case a good deal of the scanty

receipts from the produce sold would be used up in paying for lodging.

In one instance a man was forced to send home for money to pay his way

back. In another case a settler, who had packed his load on his

shoulders, lost his way in the darkness on the road home. After vainly

groping about for some time he lay down with a pine knot for a pillow

and when he woke in the morning he found himself within a few rods of

his own door.

Nottawasaga was not, like

Flos, a prohibition township. In the former whiskey was as free as

water. It was a common practice at stores to keep a barrel on tap at

which customers were free to help themselves at will. One store at

Stayner continued this practice as late as the 'sixties and in

connection with that particular store and barrel a story is told of a

hoax perpetrated by a practical joker of the day. While the barrel was

free to all who came in, it was assumed that only such as were customers

would take advantage of the hospitality offered. There was one old chap

who seldom bought anything over the counter although he frequently drank

there and a young fellow decided to cure the old toper of the habit. So

when the thirsty one came in one day, and as usual began edging his way

to the open barrel, his attention was purposely diverted for a moment

and meantime the tin cup attached to the whiskey barrel was filled with

coal oil. The oil was taken at a gulp before the taste was noticed, but

it is probable that the weakness for free drinks was cured there and

then.

Tragedy was closely

linked with comedy in the drinking habits of pioneer days. A young -man

of eighteen, with Indian blood in his veins, was noted for his strength

and courage even in a community where these qualities were a

commonplace. He could lift a stone that a team of horses found it

difficult to move, and one of his feats was to stand on his head at the

pinnacle of a newly raised barn. He could, too, hold his own with the

hardest drinkers in carrying his load of liquor. But one day he overdid

it. He accepted a wager that he could drink a pailful at one sitting. He

swallowed the lot in three gulps, staggered to a fence corner and died.

THE RUGBY SETTLEMENT

Hardships quite as great

as those borne by most of the pioneers were endured by the first

settlers between Hawkstone and Rugby, on the west side of Lake Simcoe.

"When our people came

here in the early thirties," said Jolm Robertson, a son of one of the

Rugby pioneers, "they had to bring their flour all the way from Hog's

Hollow. The flour was teamed as far as Holland Landing and then carried

by boats, manned by Indians, to Hawk-stone. From Hawkstone the settlers

packed it on their backs to Rugby, a distance of six miles, and even to

Afedonte, six miles further on. The flour was usually carried in bags,

but on one occasion Grandfather George Robertson carTied home almost a

barrel of flour on his shoulders.

'In 1833, the Government

built a grist-mill at Coldwater. This was intended for the use of the

Indians, but it served settlers about Rugby as well. Being only fourteen

miles distant, it. proved a great convenience. Even at that, however,

two days were spent going and coming with grist. At times it took

longer, as not infrequently fifty teams would arrive at the mill in one

day, and then people had to wait their turn. While waiting, the men

cooked `chokedog', a mixture of flour and water, for their food. It was

as hard as a brick on the outside and soft as blubber in the middle."

Real comfort carne,

though, when, in 1855, a man named Dallas built a mill between Orillia

and where the Hospital for Feeble-Minded now stands. The stone

foundation for this mill was laid by the father of Duncan Anderson.

[Duncan was for years a popular Farmers' Institute lecturer and later

served three terms as mayor of Orillia.] While engaged in this

foundation work Mr. Anderson Sr., lived at home, three miles away. Still

he was always at work at the mill at seven, remained until six, and

after returning home he frequently worked in the logging field until ten

at night. The old Dallas mill disappeared long ago, but part of the

foundation still standing shows that the stones were well and truly

laid.

In the first year of the

Rugby settlement, before there was enough cleared ground on which to

grow potatoes, George Tudhope, formerly clerk of Oro Township, planted

some potatoes on shares at Holland Lauding. He pitted his share when

dug, and next spring moved them to Hawkstone by boat and from Hawkstone

carried them to Rugby on his back. One spring when potatoes were

exceptionally scarce, people actually dug up the tubers they had planted

for seed in order to secure food.

THE EARLY DAYS OF INNISFIL

"I have been here in

Innisfil longer than any man now living in the township. My memory

goes back to the time

long before the railway, when the forests, which then covered the land,

were filled with game and when Indians were as numerous around Lake

Simcoe as they still are about the north shore of Georgian Bay." It was

J. L. Warnica, then in his eightieth year, but who would have passed for

less than seventy, who made this statement. The story that followed

fully warranted the expectations aroused by the introduction. When Air.

Warnica was a young man, all the merchandise received in Barrie was

teamed there from Toronto, and much of the teaming was done by Mr.

Warnica himself. "When passing over `The Ridges' I have, from an

elevation, seen teams as far north and south as the eye could reach,"

said lair. Warnica. "It was like one huge funeral procession, and it was

made up of wagons from as far away as Medford and Penetang' on the

north, as well as wagons that had drifted in from intervening side

roads.

"The Innisfil teamsters

had two favourite stopping places in Toronto. One was the Fulljames

House, at the corner of Queen and Yonge streets, and the other was the

old Post tavern nearly opposite the St. Lawrence market. The Fulljames

place stood well back from the corner and covered practically the site

now occupied by the Eaton store. Great sheds for the accommodation of

teamsters filled the yards. The corner at that time marked the northern

limits of the city. The buildings in Toronto were scattered like those

of a village. The Queen Street asylum was two miles out of town. The

father of my first wife bought ten acres and an old tavern opposite the

main gate of the asylum for one thousand dollars.

"Yes, there were plenty

of taverns in those days," continued Mr. Warnica. "Between the head of

Kempenfeldt Bay at Barrie and Yonge Street wharf in Toronto, there were

sixty-eight licensed houses—one for each mile of the road and three to

spare, besides eight or ten unlicensed places. Distilleries were also

numerous. There was one at Tollendale, opposite Barrie, and another on

the creek that runs through Allandale. These were, however, soon snuffed

out and the bulk of the business in this line passed to the Gooderhams.

Most of my freight, when I was teaming, consisted of Gooderham whiskey.

Six barrels made a load and, after being hauled all the way to Barrie,

it retailed at twenty-five cents per gallon.

"But then the freight

bill was not very high," Mr. Warnica went on. "The regular charge for

teaming a load of whiskey to Barrie was eight dollars. Out of that the

teamster had to pay for the feed of his horses, board for himself, and

the fee at seven toll gates. I remember once, when another teamster and

myself had a miscellaneous lot of merchandise for a Barrie merchant, we

were charged with the loss of a box of ribbons. I do not believe we ever

received the box, but we had to pay for it all the same. On that

occasion, when expenses had been deducted, there was just seventy-five

cents to divide between us for the round trip. After that we preferred

to haul whiskey as there was no chance of loss on that.

"If freights were not

high, expenses incurred by freighters were not extravagant either.

Supper and bed for a man and hay for his team cost fifty cents at a

wayside tavern. It is true that it was not exactly royal fare. There

were three beds in each room and two people slept in each bed. There

were no stationary wash-stands, in fact, not so much as a washstand of

any kind. A basin stood in the bar and each man took his turn in going

out to the pump for a clean up.

"Some of these stopping

places were not too warm. I well remember one night spent at McLeod's

tavern, a little north of Aurora. The building was of frame and not

plastered at that. There were two thin cotton sheets and one quilt, and

a very thin one it was, on the bed. I had

to rub my toes to keep

them from freezing in the night.

The accommodation north

of Barrie was poorer still. Once, early in March, father and I undertook

to move a camp of Indians from Tollendale to Rana. There was at that

time a tavern, known as The Half Way House, about midway between Barrie

and Orillia. We proposed to stop there for dinner, but the Highland

landlord informed us that he had no flour. `I have plenty of good

whiskey, though,' he said, evidently wondering what a man wanted to eat

for so long as he could get plenty to drink. Unable to get dinner we

decided to push on to Orillia. There we ordered dinner and supper in one

and took our Indian charges over to Rama while the meal was being

prepared. When we returned to the tavern I found, after unhitching, that

I could not get my horses into the only stable in the place as the door

was too low for the animals to pass in. The landlord proposed that I

should let them stand in the shed all night, but I was afraid that they

would perish with cold after the hard drive. So when supper was over I

started for home, where I arrived at five next morning, after having

been nearly twenty-four hours on the road.

"The roads, south as well

as north of our place, were as poor as the tavern accommodation. The low

places on Yonge Street and the Penetang' Road were covered with

corduroy, and as the logs were of uneven size you can imagine what it

was like driving over them. A little before my time a party of traders

on their way north to trade with the Indians reached Grassi. Point

toward evening. On their arrival one of the traders was taken ill, but

next day they went on to where the old Sixth Line Church now stands. The

man's condition became worse and that night he died. His body was buried

at the foot of a giant maple, which then stood just inside the present

cemetery grounds. From the tragic nature of the trader's death there

arose a story that the place was haunted, and a half-breed who then

carried the mail between Penetang' and Toronto quit his job because he

had to pass the place at night.

"I once had a bad fright,

there myself. I was on my way from 'Toronto, accompanied by my uncle in

another wagon, with a load of freight. We had been held up at Bradford

by a thunderstorm and when we reached the sixth line it was pitch dark.

A fire had been started by some men engaged during the day in improving

the road and this fire spread to the hollow stub, all that remained of

the big maple marking the grave of the trader. As I came near the spot I

beheld what seemed to be a light moving slowly up and down. I at once

thought of the spook story and my hair stood on end with fear. What I

really did see was a succession of fitful flames showing first at one

hole in the maple stub and then at another higher up or lower down. It

was all right when the explanation came but exceedingly uncomfortable

before learning the cause of the light.

"No, I was not born in

Innisfil," said Mr. Warnica as the conversation drifted off in another

direction. "I was born near Thornhill. My grandfather (Lyon) on my

mother's side established a grist-mill there before the time of Thorne,

after whom the place was named. A Pennsylvania Dutchman, Kover by name,

took a couple of stones from the creek and dressed them for grinding.

Before that we did our grinding in a coffee-mill we had brought with us.

Before that again people crushed wheat with the head of an axe in a hole

made in the top of an oak stump. This stump was on the third of Markham,

near Buttonville, and I remember quite well seeing the hole in it and

hearing the story. To my Grandfather Lyon was issued one of the first

two Crown deeds granted in Markham."

Turning once more to the

early days near Barrie, Mr. Warnica had something to say of Indian life

and the abundance of game that then filled the woods. "I have seen," he

said, "as many as one hundred Indian tepees in the woods about

Tollendale on the south side of Kempenfeldt Bay. It was an interesting

sight to watch the making of an Indian home in winter. The head of the

family, carrying bow and arrow, tomahawk and knife, strode ahead. The

mother, carrying one or two papooses on her back, as well as the

household belongings, followed. When the site selected for the camp was

reached, the Indian chopped down a few saplings with crotched tops. The

squaw meantime, with a cedar shovel, formed a circular hole in the snow.

The crotched sticks were set up around this and covered with bark or

evergreens; a fire was started in the middle of the tent, evergreen

boughs were spread on the ground and covered with fur, and, in half an

hour, the house was ready for occupation. While the work of preparation

was going on the papooses, strapped to flat hoards, were hung up on

trees by hooks at the heads of the boards. If one cried the mother would

stop work for a moment and soothe the child with a gentle rocking

accompanied by a lullaby.

"Game—bear, deer,

partridge, and pigeons—was more than abundant. I have killed partridges

with a club. I once struck down a pigeon with an ox-goad; another time,

with two shots—one fired into a flock of pigeons as they were feeding on

the ground and the other as they rose—I secured twenty-nine birds; I

have frequently brought down ten or a dozen at a single shot.

"As a boy, I have heard

the wolves howling in the woods at night, and in the morning the sweat

would pour from me with fear as I went into these same woods to hunt for

the cows. On one occasion I helped capture two young bears on the

Penetang' road opposite our place, a little south of Barrie. We cut down

the trees in which the animals had taken refuge and then killed them

with clubs.

"What became of the

pigeons? I do not know, but I have a theory. At theory is that all this

game was placed here for the use of man when no other form of food was

available and that it disappeared when the need for it no longer

existed.

"I have witnessed almost

all the changes that have taken place in Innisfil," said Mr. Warnica as

he concluded his story. "I was here at the beginning of the settlement,

and I was already a young man when the railway came. I bought my first

overcoat with money earned in making pick- and axe-handles, and cart

shafts, for use in the work of construction. I came here as an infant,

and the longest time I have spent away from home was when I put in

twenty-eight days at the World's Fair at Chicago. I was always

interested in fairs; I attended twenty-two out of twenty-four of the old

Provincials in the days when the fair was held alternately at London,

Kingston, and other places."

Mr. Warnica's first wife

was a niece of John Montgomery of Montgomery's Tavern and his second, a

niece by marriage of Samuel Lount, one of the martyrs of 'Thirty-Seven.

But Mr. Warnica himself was a mere child in the troubled times of the

'thirties and all he knew of the period before the rebellion was a mere

matter of hearsay. He told of one incident, however, that throws some

light on the conditions that helped to fan the flames of revolt.

"My uncle William," he

said, "was one of the first advocates of free schools and he once

broached the subject at a meeting at Barrie. `What do you need such

schools for?' stuttered one of the Family Compact champions. `There will

always be enough well educated Old Countrymen to transact all public

business, and we can leave Canadians to clean up the bush.' "

The sentiment thus

expressed is not wholly dead yet, although it exists in a somewhat

different form. There are still those who think they were made to ride

while others were made to he ridden.

REMINISCENCES OF A

SUNNIDALE PIONEER

One of the most

interesting and instructive accounts of pioneer life of Upper Canada

during the early part of the last century is contained in Reminiscences

of a Canadian Pioneer, by Samuel Thompson. Thompson was a man of some

education, having served a seven years' apprenticeship in London,

England, at the printing trade. He was a writer of ability and no mean

poet, and during his later years in Canada was an editor and publisher.

He remained but a short time in the bush, but the account of his

experiences throw much light on pioneer conditions.

A settler to reach Canada

from the British Isles had in nearly every case trying experiences.

Little thought was given to the comfort of the emigrants by the

transportation companies of those days, and the journey across the

Atlantic was not the least of the trials the early settlers had to

endure. Thompson's case was no exception. He and his two brothers,

Thomas and Isaac, sailed from London in the spring of 1833 in the Asia

of 500 tons, a large ship for those days. Buffeted by head winds, the

Asia spent a fortnight in the English Channel, but, a favourable breeze

springing up, they made an excellent run until the banks of Newfoundland

was reached, when it seemed that their voyage was about ended. Here they

encountered a furious storm, against which the Asia could make no

progress. To make matters worse, the vessel sprang a leak, the ballast

shifted, and. lying at an angle of fifteen degrees, she wallowed in the

tumbling waves. Crew and passengers manned the pumps continuously, but

still the water gained on them. The captain discovered that the leak was

in such a position that when running before the wind it -would be out of

water, and so to save his ship he turned about and made for the Irish

coast and succeeded in reaching Galway Bay. Here the damage was

repaired, and with the addition of some wild Irish, Roman Catholics and

Orangemen, to her list of passengers the Asia once more headed

Canadawards. On the passage the vessel was almost wrecked, when passing

through a field of icebergs, "by the sudden break-down of a huge mass as

big as a cathedral."

When Quebec was reached,

the passengers of the Asia were transferred to a fine steamer for

Montreal. At Lachine, bateaux were provided to carry them up the St.

Lawrence. While at Lachine they had a picturesque reminder of the

vastness . of the land in which they were about. to make their homes.

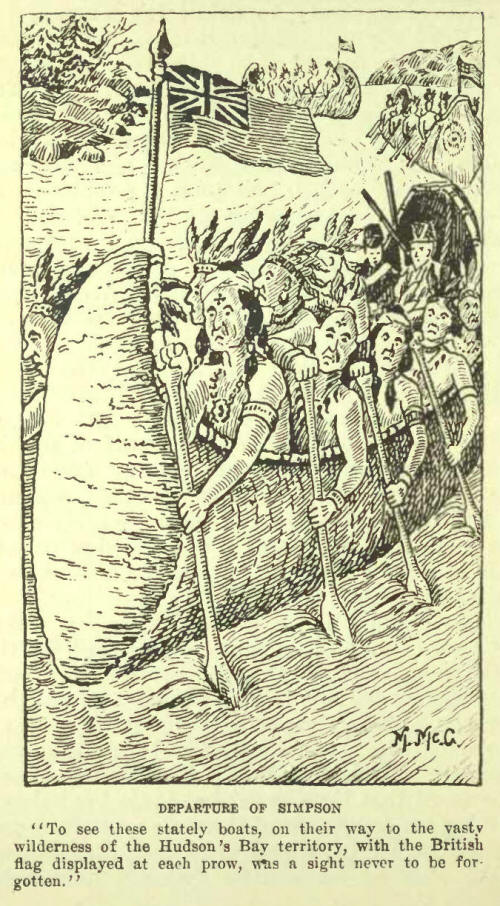

"While loading up," says

Thompson, "we were favoured with one of those accidental `bits' —as a

painter would say—which occur so rarely in a life-time. The then despot

of the North-West, Sir George Simpson, was just starting for the seat of

his government via the Ottawa River. With him were some half-dozen

officers, civil and military, and the party was escorted by six or eight

Nor'-West canoes—each thirty or forty feet long, manned by some

twenty-four Indians, in the full glory of war-paint, feathers, and most

dazzling costumes. To see these stately boats, with their no less

stately crews, gliding with measured stroke, in gallant procession, on

their way to the vasty wilderness of the Hudson's Bay territory, with

the British flag displayed at each prow, was a sight never to be

forgotten."

It is unnecessary to

detail the Thompsons' westward voyage, similar to that of other settlers

already described in this book. Sufficient to say that they reached

Little York on the steamer United Kingdom during the first week in

September, 1833, four months after leaving London. "Muddy Little York,"

as it was not undeservedly called, had then a population of about 8,500.

According to Thompson, "in addition to King street the principal

thoroughfares were Lot, Hospital, and Newgate Streets, now more

euphoniously styled Queen, Richmond, and Adelaide Streets respectively."

Where the Prince George Hotel now stands was "a wheat-field." "So well,"

writes Thompson, "did the town merit its muddy soubriquet, that in

crossing Church Street near St. James' church, boots were drawn off the

feet by the tough clay soil; and to reach our tavern on Market Lane (now

Colborne Street), we had to hop from stone to stone placed loosely along

the roadside. There was rude flagged pavement here and there, but not a

solitary planked footpath throughout the town."

The Thompsons purchased a

location ticket for twenty pounds sterling, and set out for the Lake

Simcoe district "in an open wagon without springs, loaded with the

bedding and cooking utensils of intending settlers." After a day's

journey, they reached Holland Landing and from there crossed to Barrie

in a small steamer. Barrie, at that time, consisted of "a log bakery,

two log taverns,—one of them also a store,—and a farm-house, likewise

log. Other farm-houses there were at some little distance hidden by

trees." So desolate was the prospect that some members of the party

turned back, but the Thompsons pressed on "for the unknown forest, then

reaching, unbroken, from Lake Simcoe to Lake Huron." To the Nottawasaga

river, eleven miles, "a road had been chopped and logged sixty-six feet

wide; beyond the river nothing but a bush path existed."

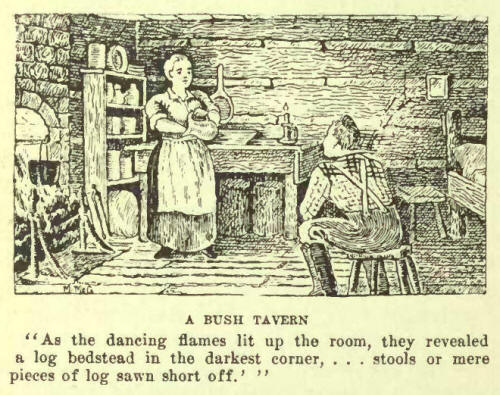

They toiled on until

nightfall, covering a distance of eight miles and at a clearing in the

forest came on a bush tavern, "a log building of a single apartment."

"The floor," writes Thompson, "was of loose split logs, hewn into some

approach to evenness with an adze; the walls of logs entire, filled in

the interstices with chips of pine, which, however, did not prevent an

occasional glimpse of the objects visible outside, and had the

advantage, moreover, of rendering a window unnecessary; the hearth was

the bare soil, the ceiling slabs of pine wood, the chimney a square hole

in the roof; the fire was literally an entire tree, branches and all,

cut into four-feet lengths, and heaped up to the height of as many

feet." As the dancing flames lit up the apartment, they revealed "a log

bedstead in the darkest corner, a small red-framed looking-glass, a

clumsy comb suspended from a nail by a string,. . . stools of various

sizes and heights, on three legs or on four, or mere pieces of log sawn

short off." The tavern was kept by a Vermonter, named Dudley Root, and

his wife, "a smart, plump, good-looking little Irish woman." The pair

evidently knew how to cater for the occasional guests, as the breakfast

provided for the Thompsons proved,—` `fine dry potatoes, roast wild

pigeon, fried pork, cakes, butter, eggs, milk, `China tea,' and

chocolate—which last (declined by the Thompsons) was a brown-coloured

extract of cherry-tree bark, sassafras root, and wild sarsaparilla."

On through the forest

they trudged looking about for a favourable location, and finally

selected a hard-wood lot in the centre of the township of Sunnidale.

Here, with the help of a hired, expert axe-man, they soon had half an

acre cleared of its "splendid maples and beeches

which it seemed almost a

profanation to destroy." In quick order they erected a log shanty,

twenty-five feet long and eighteen wide, "roofed with wooden troughs and

`chinked' with slats and moss .... At one end an open fire-place at the

other sumptuous beds laid on flatted logs, cushioned with soft hemlock

twigs, redolent of turpentine and health."

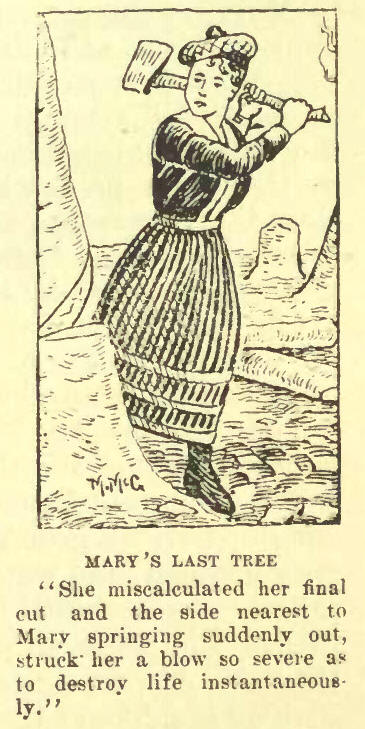

Thompson gives an

interesting account of the method of clearing the land, and in this

connection points out that in the Sunnidale district some of the young

women were almost as expert with the axe as the men. One of these,

Nary—, "daughter of an emigrant from the county of Galway ... became in

time a 'firstrate' chopper,

and would yield to none

of the new settlers in the dexterity with which she would fell, brush,

and cut up maple or beech." She and her elder sister, "neither of them

older than eighteen, would start before day-break to the nearest store,

seventeen miles off, and return the same evening laden each with a full

sack flung across the shoulder, containing about a bushel and a half, or

ninety pounds weight of potatoes." One of Mary's neighbours a young lad,

Johnny, a son of one of the earl- Scotch settlers in the Newcastle

district, who was about her own age, was a famous axe-man. Mary was

anxious to try her skill with the young Scot and got her brother, Patsy,

who was Johnny's working-mate, to vacate his place for her. She proved

herself quite as skillful as Johnny, and, it would seem, lost her heart

to him. The sequel shows to what perils the women of Ontario were

subjected in pioneer days. One day Mary was felling a huge yellow birch.

As she neared the end of her work, her mind seemed to wander from her

task and "she miscalculated her final cut and the birch, overbalancing,

split upwards, and the side nearest to Mary, springing suddenly out,

struck her a blow so severe as to destroy life instantaneously .... In a

decent coffin, contrived after many unsuccessful attempts by Johnny and

Patsy, the unfortunate girl was carried to her grave, in the same field

which she had assisted to clear." Thompson adds: "Many years have rolled

away since I stood by Mary's fresh-made grave, and it may be that Johnny

has forgotten his first love; but I was told, that no other has yet

taken the place of her, whom he once hoped to make his `bonny bride.' "

The Thompsons had some

heart-breaking experiences. "We lead," writes Thompson, "'with infinite

labour managed to clear off a small patch of ground, which we sowed with

spring wheat, and watched its growth with most intense anxiety until it

attained a height of ten inches, and began to put forth tender ears ...

. But one day in August, occurred a hailstorm such as is seldom

experienced in half a century. A perfect cataract of ice fell upon our

hapless wheat crop. Flattened hailstones, measuring two and a half

inches in diameter and seven and a half in circumference, covered the

ground several inches deep. Every blade of wheat was utterly destroyed,

and with it all our hopes of plenty for that year."

One of the worst pests

the early settlers had to contend with was the wild pigeons, a bird

that, so far as is known, is now extinct. These swept down on the land

in myriads and grain and pea fields were stripped clean by them. In

several other cases in this book these birds have been referred to, but

Thompson's account of them is most interesting. There was a pigeon-roost

a few miles distant from where he and his brothers had settled. To this

roost at the proper season "men, women, and children went by the

hundred, some with guns, but the majority with baskets, to pick up the

countless birds that had been disabled by the fall of great branches

broken off by the weight of their roosting comrades overhead. The women

skinned the birds, cut off the plump breasts, throwing the remainder

away, and packed them in barrels with salt, for keeping."

Thompson points out that

these pigeons were an important factor in connection with the vegetation

of these early days. He noticed that when land had been burnt over it

was almost immediately followed by "a spontaneous growth, first of

fireweed or wild lettuce, and secondly by a crop of young cherry trees,

so thick as to choke one another. At other spots, where pine trees had

stood for a century, the outcome of their destruction by fire was

invariably a thick growth of raspberries, with poplars of the aspen

variety." Thompson was not content with merely observing this seemingly

miraculous growth of new vegetation, he investigated the matter. ``I

scooped up," he writes, ``a panful of black soil from our clearing,

washed it, and got a small tea-cupful of cherry stones, exactly similar

to those growing in the forest." He naturally concluded that the pigeons

were responsible for the strange growth of cherry and raspberry in the

burnt, lands.

Becoming dissatisfied

with their Sunuidale lot, the Thompsons exchanged it for one in

Nottawasaga in the settlement called the Scotch line, where dwelt

Campbells, McGillivrays, McDiarmids, etc., very few of whom were able to

speak a word of English. Their life here was similar to that of other

settlers whose stories have already been told. One incident is worthy of

record as it shows the primitive condition of things in a community only

thirty-four miles from Barrie. Flora McAlmon, the wife of Malcolm

McAlmon, the most popular woman in the Scotch line settlement, died in

childbirth, largely due to the fact that no skilled physician or

experienced midwife was at hand. Her brother came to the Thompsons to

borrow pine boards to make a coffin. Excepting for some pine they had

cut down and sawn up, "there was not," says Thompson, "a foot of sawn

lumber in the settlement, and scarcely a hammer or a nail either, but

what we possessed ourselves. So, being very sorry for their affliction,

I told them they should have the coffin by next morning; and I set to

work myself, made a tolerably handsome bow, stained in black, of the

right shape and dimensions, and gave it to them at the appointed hour."

And in this rude coffin the weeping bearers bore the remains of fair

Flora McAlmon "through tangled brushwood and round upturned roots and

cradle-holes ... to the chosen grave in the wilderness where now, I

hear, stands a small Presbyterian Church in the village of Duntroon."

On several occasions

Samuel Thompson had walked to Toronto, a distance of ninety miles. In

1834, before leaving Sunnidale, he made his first trip, "equipped only

with an umbrella and a blue bag, . .. containing some articles of

clothing." The first part of his way was over a road strewn with logs

over which he had to jump every few feet. Rain came on, and as night

approached he found himself far from any human habitation. He returned

to "a newly-chopped and partially-logged clearing" he had passed on the

way. Here he found a small log hut in which the axe-men, who had been at

work, had left some fire. He "collected the half-consumed brands from

the still blazing log-heaps, to keep some warmth during the night, and

then lay down on the round logs in the hope of wooing sleep."

"But," he adds, "this was

not to be. At about nine o'clock there arose in the woods, first a sharp

snapping bark, answered by a single yelp; then two or three at

intervals. Again a silence, lasting perhaps five minutes. This kept on,

the noise increasing in frequency, and coming nearer and again nearer,

until it became impossible to mistake it for aught but the howling of

wolves. The clearing might be five or six acres. Scattered over it were

partially or wholly burnt log-heaps. I knew that wolves would not be

likely to venture among the fires, and that I was practically safe ....

I, however, kept, up my fire very assiduously, and the evil brutes

continued their concert of fiendish discords ... for many, many long

hours, until the glad beams of morning peeped through the trees; when

the wolves ceased their serenade, and I fell fast asleep, with my damp

umbrella for a pillow."

When he awoke, he

continued his journey to Bradford, where he was hospitably entertained

by Mr. Thomas Drury, and given a. letter of introduction to a man of

whom he "had occasionally heard in the bush, one William Lyon

Mackenzie." The remainder of his journey was "accomplished by stage—an

old-fashioned conveyance enough, swung on leather straps, and subject to

tremendous jerks from loose stones on the rough road, innocent of

Macadam, and full of the deepest ruts."

When the Thompsons left

London for Canada, they were sanguine "of returning in the course of six

or seven years, with plenty of money to enrich," and perhaps bring back

with them, their mother and unmarried sisters. In the meantime the

sisters came to Canada and found life on the bush farm totally unsuited

to their tastes. The brothers, too, were far from satisfied. Their

holding promised them only years of unremitting toil, with but a small

return. They saw other opportunities and so disposed of their property,

Thomas and Isaac moving with their sisters to a rented farm at Bradford

and Samuel going to Toronto, where he was long to play an active part in

the business and intellectual life of the community. |