|

1787.

ON the 10th of May,

1787, my father was settled minister of nv, Kildonan, Presbytery of

Dornoch, Sutherlandshire. The living was procured for him by the

interest of his steady and tried friend, Charles Gordon of Pulrossie.

I have been informed that, on the death of Mr. William Gunn,

minister of Golspie, that living was first procured for my father by

Mr. Gordon; but, on considering that my father was not, by his

natural capacity, well fitted for so public a place, Mr. Gordon

waived his claim in favour of Mr. Keith, then minister of Kildonan,

and, upon his translation to Golspie, my father became his

successor.

His settlement at

Kildonan was not an harmonious one. The causes of this lead me to

state candidly what I conceive to have been his personal character.

He was the sincere and uncompromising enemy of sin in every shape

and circumstance. It might present itself under all its palliatives,

alleviations, and recommendations, but his hostility to it remained

unchanged and inveterate. Then he had naturally a beautiful and

inimitable simplicity of mind, which interwove itself into his

Christian character. There was an artlessness in all he said and did

which no one could have assumed. It was in this natural simplicity

of mind, under the guidance of the Divine Spirit, that lie received

his views of Divine truth. In the confession of his faith, there was

a simplicity, solidity, and connection, all of which were

characteristic of the structure of his mind. But while I state this

as my deliberate conviction concerning him, I must also mention some

things which contributed to obscure his Christian character and to

limit his usefulness as a minister. His piety, though genuine and

vital, was slow in its growth; divine truth had made a saving

impression upon his mind, but that impression was not, at its outset

or during its progress, accompanied by any very deep convictions.

Then, again, he was not a man of intellectual force. He comprehended

a subject after much and laborious investigation, but his mental

progress was slow and tedious. His apprehension, too, was neither

quick nor far-sighted, and he was defective in the ars loquerudi.

He had a difficulty in finding words to express his ideas or to

convey his meaning, and he had a timidity amounting to shyness,

which often crippled him as a speaker. Public observation his mind

shrank from, and the effect of it upon him frequently was to make

him confused in expressing his thoughts. When he felt himself in

this uncomfortable state of mind, words invariably failed him. When

settled minister of Kildonan, therefore, his parishioners,

especially those eminent for piety, received him coldly. I may

mention specially some of those who led the opposition. The first

was an old man, an elder, who lived at Kinbrace, about six miles to

the north of the manse. The next was John MacHarlish, who lived at

Kildonan, and who was afterwards one of my father's tenants. Another

was an old man who lived at Ulbster on the Strath at Helmisdale,

about four miles to the east of the manse. Of his opponents, the

most indomitable was the eccentric John Grant, who lived at Diobal.

The opposition which all these men gave to my father's ministry was-

of the passive sort. They never attended church, but on Sabbath held

meetings of their own. They thus succeeded in alienating the minds

of my father's parishioners from his ministry, and to this might be

traced the beginning of that disaffection to the Church of Scotland

which afterwards, in my native county, prevailed so largely. This

opposition, however, was not so persevering as it was strong in its

first outset; it ultimately died away. My father's natural

disposition and manners were, to the great body of his parishioners,

irresistibly taking, and, in addition to this winning disposition,

he had also those personal attractions which never yet were

overlooked by, nor failed to have their due influence over, the mind

of a Scottish Highland Presbyterian. My mother was eminently pious.

Combined with a mild, equable temper, she possessed a deeply

reflecting and intelligent mind. In these respects, she was to my

father, who was of a temper directly the reverse, a true "helpmeet."

Their circumstances were limited, as the salary of the Dirlot

Mission never exceeded £40, and at Kildonan the stipend was under

£70. At the outset they had difficulty in getting along. Furniture

for a larger house, stocking for a considerable glebe, and a farm of

very great superficial extent, which my father took in lease,

subjected them to a far heavier outlay than they were able

adequately to meet. My mother, who; to her mild temper, united a

degree of humour, used to say, "is bochd so, is bhi bochd roimh,"

which was synonymous with the adage, "out of the fire into the

embers." My father, however, had the faculty of keeping out of debt.

He (lid not indeed succeed in avoiding it altogether, but,

notwithstanding all his difficulties, he never contracted a debt

which he could not ultimately discharge. This was owing, not to any

special shrewdness in the management of his affairs, but solely to a

native honesty, which was the leading feature of his disposition.

The natural heat of his temper, however, was troublesome both to

himself and others. His parishioners were not unfrequently scorched

by it, and my mother often had difficulty in checking its violence.

Like the foam on the water's troubled surface, it appeared only

again to disappear. No judgment of my father's principles could be

worse founded than a judgment resting on the transitory ebullitions

of his temper, which, although too easily roused, somehow or other

were invariably excited on the side of truth. His parishioners knew

this, and when the more judicious and reflecting witnessed such a

triumph of "the old Adam " over him, they never nor were much

surprised at its brief outbreaks.

The members of the

Presbytery of Dornoch when my father became connected with it were,

his maternal uncle, Mr. Thomas Mackay, minister of Lairg; Messrs

George Rainy, of Creich; John Bethune, of Dornoch; Eneas Macleod, of

Rogart; William Keith, of Golspie; Walter Ross, of Clyne; George

MacCulloch, of Loth; and William Mackenzie, of Assynt. At Lairg, Mr.

Thomas Mackay was appointed assistant and successor to his father on

the 17th November, 1749; and at the death of the latter, four years

after, the whole care of the parish devolved upon him. Of deep and

fervent piety, he was profoundly versed, not only in Scripture

doctrine, but in its life-giving influence on the heart. Prayer and

the study of the Scriptures constituted the occupation of his

private hours. When he preached, every intelligent hearer could see

that "because he believed, therefore he spoke." He was recognised as

an earnest Christian when be was but a very youthful minister, and

his ministry was signally honoured in being made instrumental for

bringing many to the knowledge of the truth. Yet with these bright

features of spiritual character, Mr. Mackay was uneven in his

temper, dogmatic in his opinions, and in his judgments, severe and

harsh. My father, who was of different disposition entirely, could

never agree with him, and felt uneasy in his society. Mr. Mackay had

a family of five. His eldest daughter, Catherine, married Captain

Donald Matheson of Shiness, by whom she had a numerous family of

sons and daughters. His eldest son, John, was one of the clerks to

the Commissioners for India, and in their service he lost his sight

and retired on a pension. He purchased the small estate of Little

Tarrel in the parish of Tarbet, to which he gave the name of

Rockfield. Air. Mackay's second son, Hugh, was a captain in the

Madras Native Cavalry, and agent for carriage and draught horses to

the Indian Army under General Wellesley, afterwards Duke of

Wellington. He was killed in the battle of Assaye, assigning the

bulk of his fortune to his elder brother, John. Mr. Mackay's

youngest son, William, was a sailor, and commanded a merchant ship

trading to India. In 1795 he was one of the survivors from the

skipwreck of the Juno, on the coast of Arracan, of which he

published an interesting narrative. He died in 1804. The youngest

daughter, Harriet, married Mr. George Gordon, minister of Loth, by

whom she had five children. Mr. ,Mackay lived to be an old man.

Towards the close of his life, and when unfit to engage in his

public duties, he employed assistants. The first of them was a Mr.

William Ross, who was very popular among the humbler classes. The

people called him, by way of respect, a "Lump of Love," but the

higher classes called him "Lumpy." He died minister of the Gaelic

Chapel, Cromarty. Mr. Mackay's other assistants were the late Mr.

James Macphail, minister of Daviot; the late Mfr George Gordon, of

Loth; and Mr Angus Kennedy. The last of these succeeded him in Lairg,

but afterwards went to Dornoch. Mr. Mackay died in 1803.

My father's next

co-presbyter, in point of seniority, was Mr. George Rainy, minister

of Creich; he was settled there in 1771. A native of Aberdeenshire,

the Gaelic was not his mother-tongue, and even after practising it

during an incumbency of 45 years he could not easily get his mouth

about it. He was a truly pious man, and if he was not successful in

adding numbers to the church, yet be was an honoured instrument in

watering and refreshing the people who were committed to his

pastoral care. His great defect was his deficiency in the language

which his parishioners best understood. In other circumstances this

drawback would have been fatal to his usefulness as a minister. But

Mr. Rainy was the very model of a sincere, practical Christian ; he

preached the gospel by his life more than by his lips. What his

tongue failed fully to explain to his flock his everyday walk

clearly conveyed; and when they connected together the doctrines

which he taught in the pulpit, his personal intercourse with each,

his zeal, his sanctified dispositions, and the warmth and

overflowing tenderness of his heart, they forgot the liberties which

lie took with their language and listened with attention, because

they were convinced that they heard the truth from the lips of one

of its most faithful preachers. Mr. Rainy married a daughter of Mr.

Gilbert Robertson, minister of Kincardine. Mrs. Rainy was pious, the

impersonation of motherly kindness, the beau ideal of a minister's

wife.

The next member of

the Presbytery whom I would mention is air. Eneas Macleod, minister

of Rogart. His father I have already noticed as the author of "Caberfeidh,"

the Gaelic satire, and well known in his native parish of Lochbroom

as a poet, by the name of "Tormaid Ban," or the fair-haired orman.

Mr. Macleod of Rogart was his second son. His eldest son was

Professor of Hebrew in the University of Glasgow, and bequeathed his

valuable library to King's College, Aberdeen, of which both he and

his brother, the minister of Rogart, were alumni. The latter was

admitted minister of that parish in 1774. Mr. Macleod was not a

popular, nor a very evangelical preacher. He had a rich vein of

humour added to great penetration and solidity of judgment, and,

though not himself a poet, he possessed a high taste for the art,

and ardently patronised it. With Rob Donn he was intimate, and he

committed to writing the poems of that hard from the poet's personal

recital. It is to this manuscript that we are indebted for the

edition of Rob Donn's poems, edited in 1829 by Dr. Mackay. Dfr.

Macleod married Jane Mackay, the daughter of a respectable farmer

who occupied the place of Clayside, now a part of the extensive

ducal manor of Dunrobin. This Mr. Mackay was a connoisseur in

card-playing, and was therefore recognised among his associates

under the name of "Hoyle." By his wife ,Mr. Macleod had four sons,

Donald, William, Hugh, and Wemyss, and three daughters, Esther,

Jean, and Elizabeth. He died on the 18th of May, 1791, and was

succeeded by the Rev. Alexander Urquhart.

John Bethune, D.D.,

minister, first of Harris, and afterwards of Dornoch, and son of Mr.

Bethune of Glenshiel, my grandfather's contemporary, "ministear na

tunn" (the barrel minister) was my father's co-presbyter for upwards

of thirty years. He was translated from Harris to Dornoch in the

year 1778. He married Barbara, daughter of Mr. Joseph Munro,

minister of Edderton in Ross-shire, by whom he had five sons, John,

Joseph, Matthew, Walter, and Robert, and three daughters, Christian,

Barbara, and Janet. Dr. Bethune was an elegant classical scholar, a

sound preacher, and one of the most finished gentlemen I ever

remember to have seen. His manners were so easy and dignified that

they would have graced the first peer of the realm, and his English

sermons, which he always read, were among the neatest compositions I

ever heard. In preaching in the Gaelic language, he used very full

notes, as his mind was of that highly-intellectual character that it

could not submit to, nor indeed be brought to work in, mere

extempore or unconnected discussions. With all his other

qualifications he had a delicate sense of propriety, and from

anything, even the slightest word, come from what quarter it might,

that touched upon this terra sacra, he shrunk back as from something

positively loathsome. He was a model Christian minister in the eye

of the world; but with all his natural talents and acquirements,

with all his orthodoxy and sentiment, and with his high sense of

moral propriety, before the keen glance of Christian penetration, he

sank at once to a much lower level. To the anxious and sincere

enquirer after truth, his sermons presented only a dreary prospect

of cold and doubtful uncertainty.

Mr. William Mackenzie

was settled minister of Assynt in 1765. He was licensed by the

Presbytery of Edinburgh, and preached his first sermon in the pulpit

of Dr. Hugh Blair. Settled as the pastor of a rude and

semi-barbarous people, in a wild secluded district, instead of

setting before them the right path by his precept and example, lie

too became as barbarous and intemperate as the worst of them. His

exhibitions in the pulpit were not only lame and unprofitable but

absolutely profane, calculated as they were to excite the ridicule

of his audience. His excesses reduced himself and his family to

great indigence. On one occasion his shoes were fairly worn out. It

was Saturday evening, and he had not a decent pair to wear next day

in going to church. He therefore despatched his kirk-officer with

all convenient speed to a David Macleod, a shoemaker, who lived at a

very considerable distance off, and who had made many pairs of shoes

before for the parish minister without having received one copper in

the way of remuneration. Next day, after delaying the service as

long as lie could, his bearer per express to the shoemaker not

having returned, Mr. Mackenzie was obliged to go to the pulpit

slip-shod as he was. In his sermon, such as it was, he had occasion

towards the close to refer to some incident in the life of David,

King of Israel. "And what said David, think ye, my hearers?" He was,

in due course, about to answer the question himself, but just at

that moment his bearer to David, the Assynt shoemaker, who had

returned, was entering in at the church door. Hearing the minister's

question he shouted out, loud enough to be heard by the whole

congregation, " What did David say?—he said indeed what I thought he

would say, that never a pair of new shoes will you get from him

until you pay the old ones." Towards the close of his life he became

quite helpless, and an assistant and successor was provided for him

in the person of Mr. Duncan Macgillivray in the year 1813. Mr.

Mackenzie died in 1816, at the advanced age of 82.

Mr. William Keith,

minister of Golspie, my father's immediate predecessor in Kildonan,

was admitted minister there in 1776. Previous to his settlement in

that parish, he was first a missionary in the county of Argyle, and

afterwards assistant to Ttr. Donald Ross, minister of Fearn. Mr.

Keith, with whom I was intimately acquainted, gave me many anecdotes

of Mr. Ross. His narrow escape from a sudden and violent death,

through the gigantic exertions of Mr. Robertson of Lochbroom (am

ministear laidir), had in his latter days considerably impaired his

judgment. Mr. Keith was not many years his assistant when, on the

death of Mr. John Ross, he was settled minister of Kildonan. He was

a man of good ability and sincere piety. His ministry as well as his

temporal circumstances at Kildonan were successful and prosperous.

Eminently practical, his doctrine did not enter very much into

theological details, but it was sound, scriptural, and edifying. He

was on the best ministerial footing with his parishioners. The

living was very small, but his wants were few. He lived frugally,

and the parishioners filled his larder with all sorts of viands,

such as mutton, eggs, butter, and cheese. He had also, as minister

of the parish, the right of fishing in the river of Helmisdale to

the extent of seven miles down its course. He married Isabella,

daughter of Mr. Patrick Grant, minister of Nigg, and had seven

children, Peter, William, and Margaret, horn at Kildonan; and

Sutherland, Elizabeth, Sophia, and Lewis, born at Golspie. Mr. Keith

was not very active among his people, being of an exceedingly easy

temperament. He was also of a very social disposition; this indeed

he indulged in to a fault. Society, good living, and the luxuries of

the table, although they never led him into any excess, yet

presented such attractions to him as often brought him in undue

intimacy with the worldly and pi ofane. After Mr. Keith had laboured

for some years at Kildonan, the parish of Golspie became vacant by

the death of Mr. Gunn; he then applied personally to the patron, who

presented him to the living. His departure was universally regretted

by the parishioners of Kildonan, who were much attached to him.

Mr. Walter Ross was

admitted minister of Clyne in the year 1777. He was the immediate

successor of Mr. Gordon. His admission was opposed by the

parishioners, who had set their affections upon a Mr. Graham, a

native of Lairg, and known to be a godly man. The then Countess of

Sutherland was an enemy of God's truth, and her practice was to

appoint, to every parish in her gift, men who in every way brought

reproach on the ministerial character. The Countess, therefore,

indignantly rejected Mr. Graham, and Mr. Ross, whose principles were

in strict accordance with those of his patron, was presented. As a

preacher, he was nothing at all, for the reason that his sermons

were not his own. As the prophet's son said of the axe, when it

dropped into the stream, so might Mr. Ross say of each of his

sermons, "Alas, master, for it was borrowed." He had a Herculean

memory, and he used to say that he had often privately read, and

afterwards, for a wager, publicly preached the sermons of his

clerical friends. His private character, as an individual, had no

moral weight, for not only was his conversation light, worldly, and

profane, but it was characterised by exaggeration and absolute

untruthfulness. He completely understood the art of money-making,

and none could exceed him in domestic and rural economy. He was a

farmer, a cattle-dealer, a housekeeper, and a first-rate sportsman;

and he knew how to turn all these different occupations to profit.

He took a Highland grazing at Grianan, on the river Brora, about ten

miles to the north of his manse, where he reared black cattle, and

sold them to great advantage, lie resided here during the summer

months, and preached on the Sabbaths, in a tent, to the inhabitants

of the more remote districts of the parish. His skill in domestic

management recommended him to the late Sir Charles Ross of Balnagown,

and so entirely did Sir Charles give up to him the economy of his

household, and so much was Mr. Ross engrossed with this, that he was

an almost constant resident at Balnagown Castle, to the total

neglect of his parochial duties. Mr. Ross was, in short, like not a

few clergymen of his party in the church of that day, such a

minister as Rob Donn, in his satire on the clergy, has so

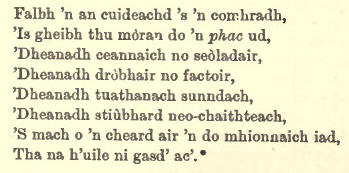

graphically depicted:—

Mr. Ross married,

some years after his settlement at Clyne, Elizabeth, daughter of

Captain John Sutherland, the occupier of the farm of Clynelish in

the vicinity of his manse, by whom he had a son and daughter. He

died in 1825, aged about 74 years.

My father's next

neighbour and co-presbyter was Mr. George Macculloch, minister of

Loth. With this short, keen, argumentative old man my earliest

recollections are associated. His youth was spent at Golspie, of

which he was the parochial schoolmaster. A native of the Black Isle,

Ross-shire, he understood the Gaelic language but imperfectly. When

at Golspie, he was the stated hearer of Mr. John Sutherland, who

afterwards became minister of Tain. Mr. Sutherland was an eminently

pious man, and a truly scriptural and orthodox divine. [Mr. John

Sutherland was translated from Golspie to Tain on 23rd June, 1752.

He died 25th Nov., 1769, in the 39th year of his ministry. He was

intimately associated with the eminent Mr. Balfour of Nigg in the

remarkable revival of true religion which, under God, by their

instrumentality, took place in Ross-shire at that period. He also

boldly contended for the rights of the Christian people in the

calling of ministers. His father was Mr. Arthur Sutherland. minister

of Edderton, a man of kindred evangelical spirit, who died in 1708,

aged 54 years; and his son was Mr. William Sutherland, minister of

Wick.—Ed.] To the doctrines of free grace he gave a more than

ordinary prominence, but this, instead of converting the

schoolmaster, only had the contrary effect of setting him to reason

against such doctrines, so that he ultimately settled down into a

bigoted and rationalistic system of Arminianism. He married

Elizabeth Forbes, daughter of the gardener at Dunrobin, by whom he

had sons and daughters. His sermons, both in Gaelic and English,

were intensely controversial. His Calvinistic antagonist stood

continually in his "mind's eye," like a phantom, and to this fancied

opponent he preached, but not to his congregation. They were

entirely neutral, and listened to his arguments and repelling of

objections very much after the manner of Uallio, who " cared for

none of these things." He argued right on, and while he wearied

himself by the "greatness of the way," he came at last to exhaust

the patience of his hearers. No friend, lay or clerical, who might

casually visit him, could remain for two hours under his roof

without being dragged into the "Arminian controversy." As he

advanced in years, although age did not cool his combative

propensities, yet his views of divine truth underwent a gradual but

most decided change. In his latter days he was much confined to his

room, and there, under the sanctified influence of bodily suffering,

he applied for strength and and patience to the volume of

inspiration. In these circumstances, his his arguments were

exchanged for deep reflection, the pride of intellect for

self-abasement, penitence, prayer, and self-enquiry. Into this

ethereal fire, the favourite "Arminian Controversy" was at last

thrown, and reduced to ashes. He died on the '27th December, 1800,

in the forty-fifth year of his ministry.

Fit for

pedlars or sailors,

Fit for drovers or factors,

Fit for active shrewd farmers,

Fit for stewards not wasteful;

Their sworn calling excepted,

Fit for everything excellent.

|