|

Birds that come in Spring — The Pewit: Pugnacity; Nests of; Cunning —

Ring Dotterel — Redshank — Oyster-Catcher: Food; Swimming of; Nest —

Curlew — Redstart — Swallows, etc.

The pewit is the first bird

that visits us for the purpose of nidification. About the middle of

February a solitary pewit appears or perhaps a pair, and I hear them in

the evening flying from the shore in order to search for worms in the

field. Towards the end of the month great flocks arrive and collect on the

sands, always, however, feeding inland. It is altogether a nocturnal bird

as far as regards feeding: at any hour of the night, and however dark it

is, if I happen to pass through the grass-fields, I hear the pewits rising

near me. Excepting to feed, they do not take much to the land till the end

of March, when, if the weather is mild, I see them all day long flying

about in their eccentric circles—generally in pairs; immediately after

they appear in this manner, they commence laying their eggs, almost always

on the barest fields, where they scratch a small hole just large enough to

contain four eggs — the usual number laid by all waders; it is very

difficult to distinguish these eggs from the ground, their colour being a

brownish-green mottled with dark spots. I often see the hooded crows

hunting the fields frequented by the pewits, as regularly as a pointer,

flying a few yards above the ground, and searching for the eggs. The

cunning crow always selects the time when the old birds are away on the

shore; as soon as he is perceived, however, the pewits all combine in

chasing him away: indeed, they attack fearlessly any bird of prey that

ventures near their breeding-ground ; and I have often detected the locale

of a stoat or weasel by the swoops of these birds : also, when they have

laid their eggs, they fight most fiercely with any other bird of their own

species which happens to alight too near them. I saw a cock pewit one day

attack a wounded male bird which came near his nest; the pugnacious little

fellow ran up to the intruder, and taking advantage of his weakness,

jumped on him, trampling upon him and pecking at his head, and then

dragging him along the ground as fiercely as a game-cock.

The hen pewit has a

peculiar instinct in misleading people as to the whereabouts of her nest:

as soon as any one appears in the field where the nest is, the bird runs

quietly and rapidly in a stooping posture to some distance from it, and

then rises with loud cries and appearance of alarm, as if her nest was

immediately below the spot she rose from. When the young ones are hatched

too, the place to look for them is not where the parent birds are

screaming and fluttering about, but at some little distance from it; as

soon as you actually come to the spot where their young are, the old birds

alight on the ground a hundred yards or so from you, watching your

movements. If, however, you pick up one of the young ones, both male and

female immediately throw off all disguise, and come wheeling and screaming

round your head, as if about to fly in your face. The young birds, when

approached, squat flat and motionless on the ground, often amongst the

weeds and grass in a shallow pool or ditch, where, owing to their colour,

it is very difficult to distinguish them from the surrounding objects.

Towards the end of March,

the ring-dotterel, the redshank, the curlew, the oyster-catcher, and some

other birds of the same kind, begin to frequent their breeding-places. On

those parts of the sandhills which are covered with small pebbles, the

ring-dotterels take up their station, uttering their plaintive and not

unmusical whistle for hours together, sometimes flitting about after each

other with a flight resembling that of a swallow, and sometimes running

rapidly along the ground, every now and then jerking up their wings till

they meet above their back. Both the bird and its eggs are exactly similar

in colour to the ground on which they breed ; this is a provision of

nature, to preserve the eggs of birds that breed on the ground from the

prying eyes of their numerous enemies, and is observable in many different

kinds; the colour of the young birds is equally favourable to their

concealment.

The redshank does not breed

on the stones or bare ground, but in some spot of rough grass; their

motions are very curious at this time of year, as they run along with

great swiftness, clapping their wings together audibly above their heads,

and flying about round and round any intruder with rapid jerks, or

hovering in the air like a hawk, all the time uttering a loud and peculiar

whistle. They lead their young to the banks of any pool or ditch at hand,

and they conceal themselves in the holes and corners close to the water's

edge.

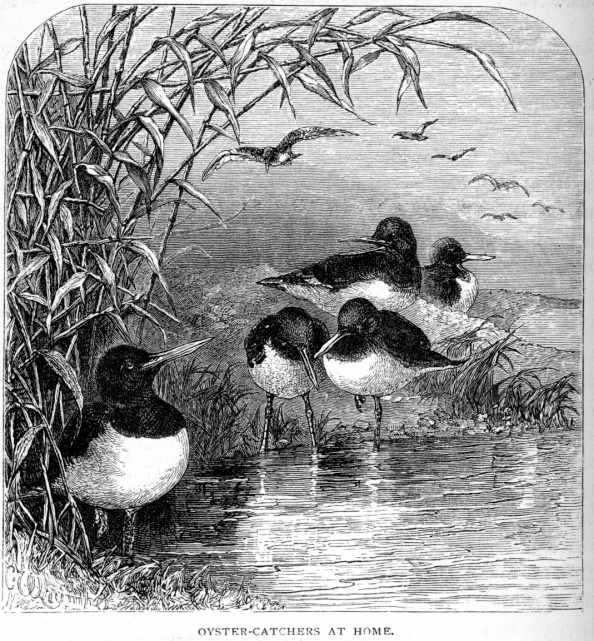

The oyster-catchers sit

quietly in pairs the chief part of the day on the banks or islands of

shingle about the river or on the shore, but resort in the evenings to the

sands in large flocks. I have often been puzzled to understand why, during

the whole of the breeding-season, the oyster-catchers remain in large

flocks along the coast, notwithstanding their duties of hatching and

rearing their young. When all the other birds are paired off, they still

every now and then collect in the same numbers as they do in winter.

They lay very large eggs,

of a greenish brown colour mottled with black; both these birds and pewits

soon become tame and familiar if kept in a garden or elsewhere, watching

boldly for the worms turned up by the gardener when digging. The

oyster-catcher's natural food appears to be shell-fish only; I see them

digging up the cockles with their powerful bill, or detaching the small

mussels from the scarps, and swallowing them whole, when not too large;

if, however, one of these birds finds a cockle too large to swallow at

once, he digs away at it with the hard point of his bill till he opens it,

and then eats the fish, leaving the shell.

It is a curious fact with

regard to this bird, that if it drops winged on the sea, it not only swims

with great ease, but dives, remaining under water for so long a time, and

rising again at such a distance, that I have known one escape out to sea

in spite of my retriever, and I have watched the bird swim gallantly and

with apparent ease across the bay, or to some bank at a considerable

distance off. The feet of the oyster-catcher seem particularly ill-adapted

for swimming, as the toes are very short and stiff in proportion to the

size of the bird. Most of the waders, when shot above the water and

winged, will swim for a short distance, but generally with difficulty;

none of them, however, excepting this bird, attempt to dive.

When in captivity the

oyster-catcher eats almost anything that is offered to it. From its

brilliant black and white plumage and red bill, as well as from its

utility in destroying slugs and snails in the garden, where it searches

for them with unceasing activity, it is both ornamental and useful, and

worthy of being oftener kept for this purpose where a garden is surrounded

by-walls ; it will, if taken young, remain with great contentment with

poultry without being confined. I have found its nest in different

localities, sometimes on the stones and sometimes on the sand close to

high-water mark — very often on the small islands and points of land about

the river, at a considerable distance from the sea; its favourite place

here is on the carse land between the two branches of the Findhorn near

the sea, where it selects some little elevation of the ground just above

the reach of the tide, but where at spring-tides the nest must be very

often entirely surrounded by the water—I never knew either this or any

bird make the mistake of building within reach of the high tides, though,

from the great difference there is in the height of the spring-tides, one

might suppose that the birds would be often led into such a scrape.

Unlike most birds of

similar kind, the sandpiper builds a substantial comfortable nest in some

tuft of grass near the riverside, well concealed by the surrounding

herbage, instead of leaving its eggs on the bare stones or sand. It is a

lively little bird, and is always associated in my mind with summer and

genial weather as it runs jerking along the water's edge, looking for

insects or flies, and uttering its clear pipe-like whistle. The young of

the sandpiper are neatly and elegantly mottled, and are very difficult to

be perceived. The eggs are brown and yellow, nearly the colour of the

withered grass and leaves with which the bird forms its nest.

Towards the end of March

the curlew begins to leave the shore, taking to the higher hills, where it

breeds, near the edge of some loch or marsh. During the season of

breeding, this-bird (though so shy and suspicious at all other times)

flies boldly round the head of any passer by with a loud screaming

whistle. The eggs are very large. When first hatched, the young have none

of the length of bill which is so distinguishing a feature in the old

bird. On the shore the curlews feed mostly on cockles and other

shell-fish, which they extract from the sand with ease, and swallow whole,

voiding the shells broken into small pieces. During open weather they

frequent the turnip and grass fields, where they appear to be busily

seeking for snails and worms.

There is no bird more

difficult to get within shot of than the curlew. Their sense of smelling

is so acute that it is impossible to get near them excepting by going

against the wind, and they keep too good a look-out to leeward to admit of

this being always done. I have frequently killed them when feeding in

fields surrounded by stone walls, by showing my hand or some small part of

my dress above the wall, when they have come wheeling round to discover

what the object was.

Besides the sea-birds that

come into this country to breed, such as sandpipers, pewits, terns, etc.,

there are some few of our smaller birds that arrive in the spring to pass

the summer here. Amongst these I may name the redstart, the spotted

flycatcher, the whitethroat, the wheatear, etc.

The redstart is not very

common: it breeds in several places, however, up the Findhorn; at Logie,

for instance, where year after year it builds in an old ivy-covered wall.

The young, when able to fly, appear often in my garden for a few weeks,

actively employed in doing good service, killing numbers of insects; and

every spring a pair or two of flycatchers breed in one of the fruit-trees

on the wall, building, as it were, only half a nest, the wall supplying

the other half. They cover the nest most carefully with cobwebs, to make

it appear like a lump of this kind of substance left on the wall; indeed,

I do not know any nest more difficult to distinguish. It is amusing to see

the birds as they dash off from the top of the wall in pursuit of some fly

or insect, which they catch in the air and carry to their young. The

number of insects which they take to their nest in the course of

half-an-hour is perfectly astonishing.

Another bird that comes

every spring to the same bush to breed is the pretty little whitethroat.

On the lawn close to my house a pair comes to the same evergreen, at the

foot of which on the ground, they build their nest, carrying to it an

immense quantity of feathers, wool, etc. The bird sits fearlessly, and

with full confidence that she will not be disturbed, although the grass is

mown close up to her abode; and she is visited at all hours by the

children, who take a lively interest in her proceedings. She appears quite

acquainted with them all, sitting snugly in her warmly feathered nest,

with nothing visible but her bright black eyes and sharp-pointed bill. As

soon as her eggs are hatched, she and her mate are in a great bustle,

bringing food to their very tiny offspring—flying backwards and forwards

all day with caterpillars and grubs.

Both this and the larger

kind of whitethroat which visits us have a lively and pleasing song. They

frequently make their nest on the ground in the orchard, amongst the long

grass, arching it over in the most cunning manner, and completely

concealing it. When they leave their eggs to feed, a leaf is laid over the

entrance of the nest to hide it; in fact, nothing but the eyes of children

(who in nest-finding would beat Argus himself) could ever discover the

abode of the little whitethroat. Before they leave this country, these

birds collect together, and are seen searching the hedges for insects in

considerable but scattered flocks. They frequently fly in at the open

windows in pursuit of flies, and chase them round the room quite

fearlessly. The gardener accuses them of destroying quantities of

cherries, by piercing them with their bills : they certainly do so, but I

am always inclined to suppose that it is only the diseased fruit that they

attack in this way, or that which has already been taken possession of by

small insects.

The wheatear does not

arrive till the first week of April, when they appear in considerable

numbers on the sand-hills, flying in and out of the rabbit-holes and

broken banks, in concealed corners of which they hatch. Their eggs are

peculiarly beautiful, being of a pale blue delicately shaded with a darker

colour at one end. Though of such repute in the south of England, it is

not ever sought after here. As a boy, on the Wiltshire downs, I used to be

an adept at catching them in horsehair nooses, as we used to consider them

particularly good eating. The shepherds there, as well as on the South

downs, make a considerable addition to their income by catching wheatears

and sending them to the London and Brighton markets.

The swallows and swifts

arrive also about the middle of April. It is a curious thing to observe

how a pair of swallows season after season build their nest in the same

angle of a window, or corner of a wall, coming immediately to the same

spot, after their long absence and weary flight, and either repairing

their old residence or building a new one.

Great numbers of sand

martins build in the banks of the river, returning to the same places

every year, and after clearing out their holes, they carry in a great

quantity of feathers and dried grass, which they lay loosely at the end of

their subterranean habitation.

The swifts appear always to

take up their abode about the highest buildings in the towns and villages,

flying and screaming like restless spirits round and round the church

steeple for hours together, sometimes dashing in at a small hole under the

eaves of the roof, or clinging with their hard and powerful claws to the

perpendicular walls; at other times they seem to be occupied the whole day

in darting like arrows along the course of the burn in pursuit of the

small gnats, of which they catch great numbers in their rapid flight. I

have found in the throat of both swift and martin a number of small flies

sticking together in a lump as large as a marble, and though quite alive

unable to escape. It is probably with these that they feed their young,

for the food of all swallows consisting of the smaller gnats and flies,

they cannot carry them singly to their nests, but must wait till they have

caught a good quantity.

We are visited too by that

very curious little bird the tree-creeper, Certhea familiaris,

whose rapid manner of running round the trunk of a tree in search of

insects is most amusing. Though not exactly a bird of passage, as it is

seen at all seasons, it appears occasionally to vanish from a district for

some months, and then to return, without reference to the time of year. I

found one of their nests built within an outbuilding, which the bird

entered by a small opening at the top of the door.

|