|

Roe: Mischief done by — Fawns — Tame Roe — Boy killed by Roe — Hunting

Roe: Artifices of — Shooting Roe — Unlucky shot — Change of colour —

Swimming — Cunning Roe.

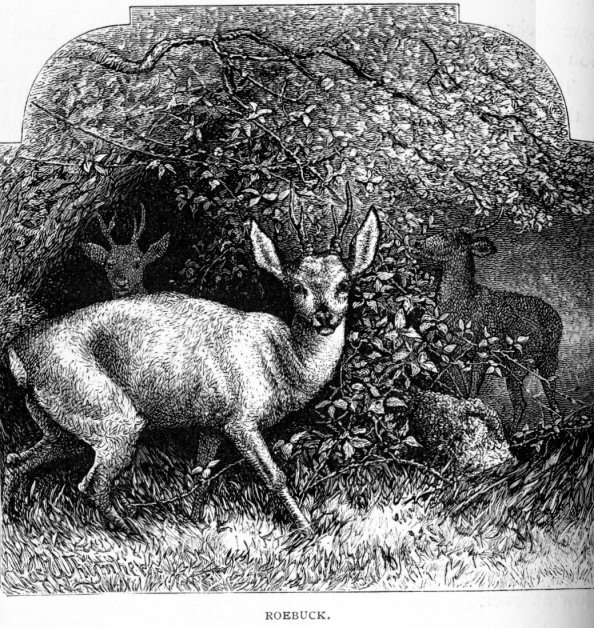

As the spring advances, and the larch and

other deciduous trees again put out their foliage, I see the tracks of roe

and the animals themselves in new and unaccustomed places. They now betake

themselves very much to the smaller and younger plantations, where they

can find plenty of one of their most favourite articles of food—the shoots

of the young trees. Much as I like to see these animals (and certainly the

roebuck is the most perfectly formed of all deer), I must confess that they commit great havoc

in plantations of hard wood. As fast as the young oak trees put out new

shoots the roe nibble them off, keeping the trees from growing above three

or four feet in height by constantly biting off the leading shoot. Besides

this, they peel the young larch with both their teeth and horns, stripping

them of their bark in the neatest manner imaginable. One can scarcely

wonder at the anathemas uttered against them by proprietors of young

plantations. Always graceful, a roebuck is peculiarly so when stripping

some young tree of its leaves, nibbling them off one by one in the most

delicate and dainty manner. I have watched a roe strip the leaves off a

long bramble shoot, beginning at one end and nibbling off every leaf My

rifle was aimed at his heart and my finger was on the trigger, but I made

some excuse or other to myself for not killing him, and left him

undisturbed—his beauty saved him. The leaves and flowers of the wild

rose-bush are another favourite food of the roe. just before they produce

their calves the does wander about a great deal, and seem to avoid the

society of the buck, though they remain together during the whole autumn

and winter. The young roe is soon able to escape from most of its enemies.

For a day or two it is quite helpless, and frequently falls a prey to the

fox, who at that time of the year is more ravenous than at any other, as

it then has to find food to satisfy the carnivorous appetites of its own

cubs. A young roe, when caught unhurt, is not difficult to rear, though

their great tenderness and delicacy of limb makes it not easy to handle

them without injuring them. They soon become perfectly tame and attach

themselves to their master. When in captivity they will eat almost

anything that is offered to them, and from this cause are frequently

destroyed, picking up and swallowing some indigestible substance about the

house. A tame buck, however, becomes a dangerous pet; for after attaining

to his full strength he is very apt to make use of it in attacking people

whose appearance he does not like. They Particularly single out women and

children as their victims, and inflict severe and dangerous wounds with

their sharp-pointed horns, and notwithstanding their small size, their

strength and activity make them a very unpleasant adversary. One day, at a

kind of public garden near Brighton, I saw a beautiful but very small

roebuck in an enclosure fastened with a chain, which seemed strong enough

and heavy enough to hold and weigh down an elephant. Pitying the poor

animal, an exile from his native land, I asked what reason they could have

for ill-using him by putting such a weight of iron about his neck. The

keeper of the place, however, told me that small as the roebuck was, the

chain was quite necessary, as he had attacked and killed a boy of twelve

years old a few days before, stabbing the poor fellow in fifty places with

his sharp-pointed horns. Of course I had no more to urge in his behalf. In

its native wilds no animal is more timid, and eager to avoid all risk of

danger. The roe has peculiarly acute organs of sight, smelling, and

hearing, and makes good use of all three in avoiding its enemies.

In shooting roe, it depends so much on the

cover and other local causes whether dogs or beaters should be used, that

no rule can be laid down as to which is best. Nothing is more exciting

than running roe with beagles, where the ground is suitable, and the

covers so situated that the dogs and their game are frequently in sight.

The hounds for roe-shooting should be small and slow. Dwarf harriers are

the best, or good - sized rabbit-beagles, where the ground is not too

rough. The roe, when hunted by small dogs of this kind, does not make

away, but runs generally in a circle, and is seldom above a couple of

hundred yards ahead of the beagles, stopping every now and then to listen,

and allowing them to come very near, before he goes off again; in this

way, giving the sportsman a good chance of knowing where the deer is

during most of the run. Many people use fox-hounds for roe-shooting, but

generally these dogs run too fast, and press the roebuck so much that he

will not stand it, but leaves the cover, and goes straightway out of reach

of the sportsman, who is left to cool himself without any hope of a shot.

Besides this, you entirely banish roe from the cover if you hunt them

frequently with fast hounds, as no animal more delights in quiet and

solitude, or will less put up with too much driving. In most woods beaters

are better for shooting roe with than dogs, though the combined cunning

and timidity of the animal frequently make it double back through the

midst of the rank of beaters; particularly if it has any suspicion of a

concealed enemy, in consequence of having scented or heard the shooters at

their posts, for it prefers facing the shouts and noise of the beaters to

passing within reach of a hidden danger, the extent and nature of which it

has not ascertained. By taking advantage of the animal's timidity and

shyness in this respect, I have frequently got shots at roe in large woods

by placing people in situations where the animal could smell them but not

see them, thus driving it back to my place of concealment. Though they

generally prefer the warmest and driest part of the woods to lie in, I

have sometimes, when looking for ducks, started roe in the marshy grounds,

where they lie close in the tufts of long heather and rushes. Being much

tormented with ticks and wood-flies, they frequently in the hot weather

betake themselves not only to these marshy places, but even to the fields

of high corn, where they sit in a form like a hare. Being good swimmers,

they cross rivers without hesitation in their way to and from their

favourite feeding-places; indeed, I have often known roe pass across the

river daily, living on one side, and going to feed every evening on the

other. Even when wounded, I have seen a roebuck beat three powerful and

active dogs in the water, keeping ahead of them, and requiring another

shot before he was secured. Though very much attached to each other, and

living mostly in pairs, I have known a doe take up her abode for several

years in a solitary strip of wood. Every season she crossed a large extent

of hill to find a mate, and returned after two or three weeks' absence.

When her young ones, which she produced ever year, were come to their full

size, they always went away, leaving their mother in solitary possession

of her wood.

The roe almost always keep to woodland, but I

have known a stray roebuck take to lying out on the hill at some distance

from the covers. I had frequently started this buck out of glens and

hollows several miles from the woods. One day, as I was stalking some

hinds in a broken part of the hill, and had got within two hundred yards

of one of them, a fine fat barren hind, the roebuck started out of a

hollow between me and the red deer, and galloping straight towards them,

gave the alarm, and they all made off. The buck, however, got confused by

the noise and galloping of the larger animals, and, turning back, passed

me within fifty yards. So, to punish him for spoiling my sport, I took a

deliberate aim as he went quickly but steadily on, and killed him dead. I

happened to be alone that day, so I shouldered my buck and walked home

with him, a three hours' distance of rough ground, and I was tired enough

of his weight before I reached the house. In shooting roe, shot is at all

times far preferable to ball. The latter, though well aimed, frequently

passes clean through the animal, apparently without injuring him, and the

poor creature goes away to die in some hidden corner; whereas a charge of

shot gives him such a shock that he drops much more readily to it than to

a rifle-ball, unless, indeed, the ball happens to strike the heart or

spine. Having killed roe constantly with both rifle and gun, small shot

and large, I am inclined to think that the most effective charge is an

Eley's cartridge with No. 2 'shot in it. I have, when woodcock-shooting,

frequently killed roe with No. 6 shot, as when they are going across and

are shot well forward, they are as easy to kill as a hare, though they

will carry off a great deal of shot if hit too far behind. No one should

ever shoot roe without some well-trained dog to follow them when wounded;

as no animal is more often lost when mortally wounded.

Where numerous, roe are very mischievous to

both corn and turnips, eating and destroying great quantities, and as they

feed generally in the dark, lying still all day, their devastations are

difficult to guard against. Their acute sense of smelling enables them to

detect the approach of any danger, when they bound off to their coverts,

ready to return as soon as it is past. In April they go great distances to

feed on the clover-fields, where the young plants are then just springing

up. In autumn, the ripening oats are their favourite food, and in winter,

the turnips, wherever these crops are at hand, or within reach from the

woods. A curious and melancholy accident happened in a parish situated in

one of the eastern counties of Scotland a few years ago. Perhaps the most

extraordinary part of the story is that it is perfectly true. Some idle

fellows of the village near the place where the catastrophe happened

having heard that the roe and deer from the neighbouring woods were in the

habit of feeding in some fields of high corn, two of them repaired to the

place in the dusk of the evening with a loaded gun, to wait for the

arrival of the deer at their nightly feeding ground. They had waited some

time, and the evening shades were making all objects more and more

indistinct every moment, when they heard a rustling in the standing corn

at a short distance from them, and looking in the direction, they saw some

large animal moving. Having no doubt that it was a deer that they saw, the

man who had the gun took his aim, his finger was on the trigger, and his

eye along the barrel; he waited, however, to get a clearer view of the

animal, which had ceased moving. At this instant, his companion, who was

close to him, saw, to his astonishment, the flash of a gun from the spot

where the supposed deer was, and almost before he heard the report his

companion fell back dead upon him, and with the same ball he himself

received a mortal wound. The horror and astonishment of the author of this

unlucky deed can scarcely be imagined when, on running up, he found,

instead of a deer, one man lying dead and another senseless and mortally

wounded. Luckily, as it happened, the wounded man lived long enough to

declare before witnesses that his death was occasioned solely by accident,

and that his companion, at the moment of his being killed, was aiming at

the man who killed them. The latter did not long survive the affair.

Struck with grief and sorrow at the mistake he had committed, his mind and

health gave way, and he died soon afterwards.

The difference in the colour and kind of hair

that a roe's skin is covered with, at different seasons of the year, is

astonishingly great. From May to October they are covered with bright red

brown hair, and but little of it. In winter their coat is a fine dark

mouse-colour, very long and close, but the hair is brittle, and breaks

easily in the hand like dried grass. When run with greyhounds, the roebuck

at first leaves the dogs far behind, but if pressed and unable to make his

usual cover, he appears to become confused and exhausted, his bounds

become shorter, and he seems to give up the race. In wood, when driven,

they invariably keep as much as they can to the closest portions of the

cover, and in going from one part to another follow the line where the

trees stand nearest to each other, avoiding the more open parts as long as

possible. For some unknown reason, as they do it without any apparent

cause, such as being hard hunted, or driven by want of food, the roe

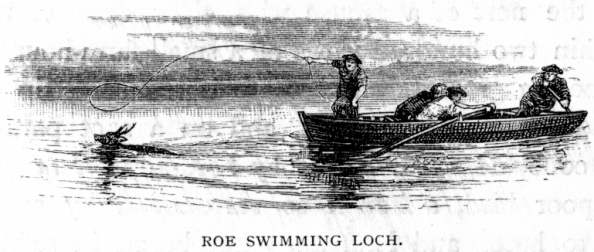

sometimes take it into their heads to swim across wide pieces of water,

and even arms of the sea. I have known roe caught by boatmen in the

Cromarty Firth, swimming strongly across the entrance of the bay, and

making good way against the current of the tide, which runs there with

great rapidity. Higher up the same firth, too, roe have been caught when

in the act of crossing. When driven by hounds, I have seen one swim Loch

Ness. They are possessed of great cunning in doubling and turning to elude

these persevering enemies. I used to shoot roe to fox-hounds, and one day

was much amused by watching an old roebuck, who had been run for some time

by three of my dogs. I was lying concealed on a height above him, and saw

the poor animal go upon a small mound covered with young fir-trees. He

stood there till the hounds were close on him, though not in view; then

taking a great leap at right angles to the course in which he had before

been running, he lay flat down with his head on the ground, completely

throwing out the hounds, who had to cast about in order to find his track

again; when one bitch appeared to be coming straight upon the buck, he

rose quietly up, and crept in a stooping position round the mound, getting

behind the dogs. In this way, on a very small space of ground, he managed

for a quarter of an hour to keep out of view of, though close to, three

capital hounds, well accustomed to roe-hunting. Sometimes he squatted flat

on the ground, and at others leaped off at an angle, till having rested

himself, and the hounds having made a wide cast, fancying that he had left

the place, the buck took an opportunity to slip off unobserved, and

crossing an opening in the wood, came straight up the hill to me, when I

shot him.

The greatest drawback to preserving roe to any

great extent is, that they are so shy and nocturnal in their habits that

they seldom show themselves in the daytime. I sometimes see a roe passing

like a shadow through the trees, or standing gazing at me from a distance

in some sequestered glade; but, generally speaking, they are no ornament

about a place, their presence being only known by the mischief they do to

the young plantations and to the crops. A keeper in Kincardineshire this

year told me that he had often early in the morning counted above twenty

roe in a single turnip-field. As for the sport afforded by shooting them,

I never killed one without regretting it, and wishing that I could bring

the poor animal to life again. I do not think that roe are sufficiently

appreciated as venison, yet they are excellent eating when killed in

proper season, between October and February, and of a proper age. In

summer the meat is not worth cooking, being dry, and sometimes rank.

|