I got this file from the

Project Guttenberg and you can download the text

file here.

CONTENTS

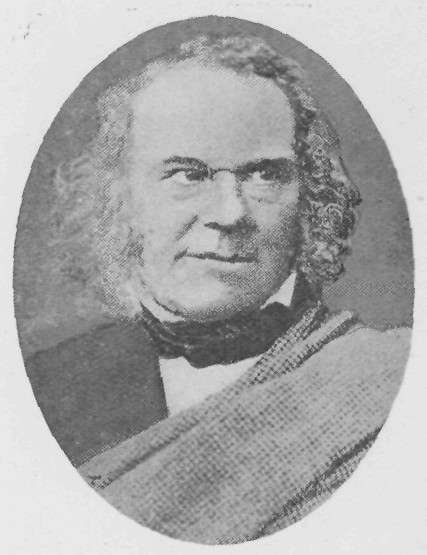

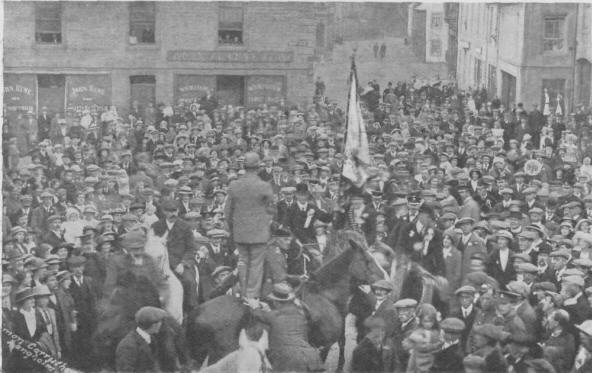

FROM A PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN DURING HIS CANDIDATURE FOR THE

REPRESENTATION OF THE CARNAVON BOROUGHS 1906

FROM JOHN O' GROAT'S TO LAND'S END

OR 1372 MILES ON FOOT

A BOOK OF DAYS AND CHRONICLE OF ADVENTURES BY TWO PEDESTRIANS ON TOUR

1916

FOREWORD

When Time, who steals our hours away.

Shall steal our pleasures too;

The memory of the past shall stay

And half our joys renew.

As I grow older my thoughts often revert to the past, and

like the old Persian poet, Khosros, when he walked by the churchyard and

thought how many of his friends were numbered with the dead, I am often

tempted to exclaim: "The friends of my youth! where are they?" but there

is only the mocking echo to answer, as if from a far-distant land,

"Where are they?"

"One generation passeth away; and another generation

cometh," and enormous changes have taken place in this country during

the past seventy years, which one can only realise by looking back and

comparing the past with the present.

The railways then were gradually replacing the

stage-coaches, of which the people then living had many stories to tell,

and the roads which formerly had mostly been paved with cobble or other

stones were being macadamised; the brooks which ran across the surface

of the roads were being covered with bridges; toll-gates still barred

the highways, and stories of highway robbers were still largely in

circulation, those about Dick Turpin, whose wonderful mare "Black Bess"

could jump over the turnpike gates, being the most prominent, while

Robin Hood and Little John still retained a place in the minds of the

people as former heroes of the roads and forests.

Primitive methods were still being employed in

agriculture. Crops were cut with scythe and sickle, while old

scythe-blades fastened at one end of a wooden bench did duty to cut

turnips in slices to feed the cattle, and farm work generally was

largely done by hand.

At harvest time the farmers depended on the services of

large numbers of men who came over from Ireland by boat, landing at

Liverpool, whence they walked across the country in gangs of twenty or

more, their first stage being Warrington, where they stayed a night at

Friar's Green, at that time the Irish quarter of the town. Some of them

walked as far as Lincolnshire, a great corn-growing county, many of them

preferring to walk bare-footed, with their shoes slung across their

shoulders. Good and steady walkers they were too, with a military step

and a four-mile-per-hour record.

The village churches were mostly of the same form in

structure and service as at the conclusion of the Civil War. The old oak

pews were still in use, as were the galleries and the old "three-decker"

pulpits, with sounding-boards overhead. The parish clerk occupied the

lower deck and gave out the hymns therefrom, as well as other notices of

a character not now announced in church. The minister read the lessons

and prayers, in a white surplice, from the second deck, and then, while

a hymn was being sung, he retired to the vestry, from which he again

emerged, attired in a black gown, to preach the sermon from the upper

deck.

The church choir was composed of both sexes, but not

surpliced, and, if there was no organ, bassoons, violins, and other

instruments of music supported the singers.

The churches generally were well filled with worshippers,

for it was within a measurable distance from the time when all

parishioners were compelled to attend church. The names of the farms or

owners appeared on the pew doors, while inferior seats, called free

seats, were reserved for the poor. Pews could be bought and sold, and

often changed hands; but the squire had a large pew railed on from the

rest, and raised a little higher than the others, which enabled him to

see if all his tenants were in their appointed places.

The village inns were generally under the shadow of the

church steeple, and, like the churches, were well attended, reminding

one of Daniel Defoe, the clever author of that wonderful book Robinson

Crusoe, for he wrote:

Wherever God erects a house of prayer,

The Devil always builds a chapel there;

And 'twill be found upon examination,

The Devil has the largest congregation.

The church services were held morning and afternoon,

evening service being then almost unknown in country places; and between

the services the churchwardens and other officials of the church often

adjourned to the inn to hear the news and to smoke tobacco in long clay

pipes named after them "churchwarden pipes"; many of the company who

came from long distances remained eating and drinking until the time

came for afternoon service, generally held at three o'clock.

The landlords of the inns were men of light and leading,

and were specially selected by the magistrates for the difficult and

responsible positions they had to fill; and as many of them had acted as

stewards or butlers—at the great houses of the neighbourhood, and

perhaps had married the cook or the housekeeper, and as each inn was

required by law to provide at least one spare bedroom, travellers could

rely upon being comfortably housed and well victualled, for each

landlord brewed his own beer and tried to vie with his rival as to which

should brew the best.

Education was becoming more appreciated by the poorer

people, although few of them could even write their own names; but when

their children could do so, they thought them wonderfully clever, and

educated sufficiently to carry them through life. Many of them were

taken away from school and sent to work when only ten or eleven years of

age!

Books were both scarce and dear, the family Bible being,

of course, the principal one. Scarcely a home throughout the land but

possessed one of these family heirlooms, on whose fly-leaf were recorded

the births and deaths of the family sometimes for several successive

generations, as it was no uncommon occurrence for occupiers of houses to

be the descendants of people of the same name who had lived in them for

hundreds of years, and that fact accounted for traditions being handed

down from one generation to another.

Where there was a village library, the books were chiefly

of a religious character; but books of travel and adventure, both by

land and sea, were also much in evidence, and Robinson

Crusoe, Captain Cook's Three Voyages round the World, and the Adventures

of Mungo Park in Africa were

often read by young people. The story of Dick Whittington was another

ideal, and one could well understand the village boys who lived near the

great road routes, when they saw the well-appointed coaches passing on

their way up to London, being filled with a desire to see that great

city, whose streets the immortal Dick had pictured to himself as being

paved with gold, and to wish to emulate his wanderings, and especially

when there was a possibility of becoming the lord mayor.

The bulk of the travelling in the country was done on

foot or horseback, as the light-wheeled vehicles so common in later

times had not yet come into vogue. The roads were still far from safe,

and many tragedies were enacted in lonely places, and in cases of murder

the culprit, when caught, was often hanged or gibbeted near the spot

where the crime was committed, and many gallows trees were still to be

seen on the sides of the highways on which murderers had met with their

well-deserved fate. No smart service of police existed; the parish

constables were often farmers or men engaged in other occupations, and

as telegraphy was practically unknown, the offenders often escaped.

The Duke of Wellington and many of his heroes were still

living, and the tales of fathers and grandfathers were chiefly of a

warlike nature; many of them related to the Peninsula War and Waterloo,

as well as Trafalgar, and boys were thus inspired with a warlike and

adventurous spirit and a desire to see the wonders beyond the seas.

It was in conditions such as these that the writer first

lived and moved and had his being, and his early aspirations were to

walk to London, and to go to sea; but it was many years before his

boyish aspirations were realised. They came at length, however, but not

exactly in the form he had anticipated, for in 1862 he sailed from

Liverpool to London, and in 1870 he took the opportunity of walking back

from London to Lancashire in company with his brother. We walked by a

circuitous route, commencing in an easterly direction, and after being

on the road for a fortnight, or twelve walking days, as we did not walk

on Sundays, we covered the distance of 306 miles at an average of

twenty-five miles per day.

We had many adventures, pleasant and otherwise, on that

journey, but on the whole we were so delighted with our walk that, when,

in the following year, the question arose. "Where shall we walk this

year?" we unanimously decided to walk from John o' Groat's to Land's

End, or, as my brother described it, "from the top of the map to the

bottom."

It was a big undertaking, especially as we had resolved

not to journey by the shortest route, but to walk from one great object

of interest to another, and to see and learn as much as possible of the

country we passed through on our way. We were to walk the whole of the

distance between the north-eastern extremity of Scotland and the

south-western extremity of England, and not to cross a ferry or accept

or take a ride in any kind of conveyance whatever. We were also to

abstain from all intoxicating drink, not to smoke cigars or tobacco, and

to walk so that at the end of the journey we should have maintained an

average of twenty-five miles per day, except Sunday, on which day we

were to attend two religious services, as followers of and believers in

Sir Matthew Hale's Golden Maxim:

A

Sabbath well spent brings a week of content

And Health for the toils of

to-morrow;

But a Sabbath profaned,

WHATE'ER MAY BE GAINED.

Is a certain forerunner of

Sorrow.

With the experience gained in our walk the previous year,

we decided to reduce our equipment to the lowest possible limit, as

every ounce had to be carried personally, and it became a question not

of how much luggage we should take, but of how little; even maps were

voted off as encumbrances, and in place of these we resolved to rely

upon our own judgment, and the result of local inquiries, as we

travelled from one great object of interest to another, but as these

were often widely apart, as might be supposed, our route developed into

one of a somewhat haphazard and zigzag character, and very far from the

straight line.

We each purchased a strong, black leather handbag, which

could either be carried by hand or suspended over the shoulder at the

end of a stick, and in these we packed our personal and general luggage;

in addition we carried a set of overalls, including leggings, and armed

ourselves with stout oaken sticks, or cudgels, specially selected by our

local fencing master. They were heavily ferruled by the village

blacksmith, for, although we were men of peace, we thought it advisable

to provide against what were known as single-stick encounters, which

were then by no means uncommon, and as curved handles would have been

unsuitable in the event of our having to use them either for defensive

or offensive purposes, ours were selected with naturally formed knobs at

the upper end.

Then there were our boots, which of course were a matter

of the first importance, as they had to stand the strain and wear and

tear of a long journey, and must be easy fitting and comfortable, with

thick soles to protect our feet from the loose stones which were so

plentiful on the roads, and made so that they could be laced tightly to

keep out the water either when raining or when lying in pools on the

roads, for there were no steam-rollers on the roads in those days.

In buying our boots we did not both adopt the same plan.

I made a special journey to Manchester, and bought the strongest and

most expensive I could find there; while my brother gave his order to an

old cobbler, a particular friend of his, and a man of great experience,

who knew when he had hold of a good piece of leather, and to whom he had

explained his requirements. These boots were not nearly so smart looking

as mine and did not cost as much money, but when I went with him for the

boots, and heard the old gentleman say that he had fastened a piece of

leather on his last so as to provide a corresponding hole inside the

boot to receive the ball of the foot, I knew that my brother would have

more room for his feet to expand in his boots than I had in mine. We

were often asked afterwards, by people who did not walk much, how many

pairs of boots we had worn out during our long journey, and when we

replied only one each, they seemed rather incredulous until we explained

that it was the soles that wore out first, but I had to confess that my

boots were being soled the second time when my brother's were only being

soled the first time, and that I wore three soles out against his two.

Of course both pairs of boots were quite done at the conclusion of our

walk.

Changes of clothing we were obliged to have sent on to us

to some railway station, to be afterwards arranged, and soiled clothes

were to be returned in the same box. This seemed a very simple

arrangement, but it did not work satisfactorily, as railways were few

and there was no parcel-post in those days, and then we were always so

far from our base that we were obliged to fix ourselves to call at

places we did not particularly want to see and to miss others that we

would much rather have visited. Another objection was that we nearly

always arrived at these stations at inconvenient times for changing

suits of clothes, and as we were obliged to do this quickly, as we had

no time to make a long stay, we had to resort to some amusing devices.

We ought to have begun our journey much earlier in the

year. One thing after another, however, prevented us making a start, and

it was not until the close of some festivities on the evening of

September 6th, 1871, that we were able to bid farewell to "Home, sweet

home" and to journey through what was to us an unknown country, and

without any definite idea of the distance we were about to travel or the

length of time we should be away.

HOW WE GOT TO JOHN O' GROAT'S

Sept. 7. Warrington to Glasgow by

train—Arrived too late to catch the boat on the Caledonian Canal for

Iverness—Trained to Aberdeen.

Sept. 8. A day in the "Granite City"—Boarded the s.s. St.

Magnus intending to

land at Wick—Decided to remain on board.

Sept. 9. Landed for a short time at Kirkwall in the Orkney

Islands—During the night encountered a storm in the North Sea.

Sept. 10. (Sunday).

Arrived at Lerwick in the Shetland Islands at 2 a.m.

Sept. 11. Visited Bressay Island and the Holm of Noss—Returned to St.

Magnus at night.

Sept. 12. Landed again at Kirkwall—Explored Cathedral—Walked across

the Mainland of the Orkneys to Stromness, visiting the underground

house at Maeshowe and the Standing Stones at Stenness on our way.

Sept. 13. Visited the Quarries where Hugh Miller made his wonderful

geological researches—Explored coast scenery, including the Black

Craig.

Sept. 14. Crossed the Pentland Firth in a sloop—Unfavourable wind

prevented us sailing past the Old Man of Hoy, so went by way of Lang

Hope and Scrabster Roads, passing Dunnet Head on our way to Thurso,

where we landed and stopped for the night.

Sept. 15. Travelled six miles by the Wick coach and walked the

remaining fifteen miles to John o' Groat's—Lodged at the "Huna Inn."

Sept. 16. Gathered some wonderful shells on the beach and explored

coast scenery at Duncansbay.

Sept. 17. (Sunday).

Visited a distant kirk with the landlord and his wife and listened

to a wonderful sermon.

OUR ROUTE FROM JOHN O' GROAT'S TO LAND'S END

¶ Indicates the day's journey. ¶¶ Indicates where Sunday

was spent.

FIRST WEEK'S JOURNEY — Sept. 18 to 24.

"Huna Inn" — Canisbay — Bucholie Castle — Keiss — Girnigoe —

Sinclair — Noss Head — Wick — or ¶ Wick Harbour — Mid Clyth —

Lybster — Dunbeath ¶ Berriedale — Braemore — Maidens Paps Mountain —

Lord Galloway's Hunting-box — Ord of Caithness — Helmsdale ¶ Loth —

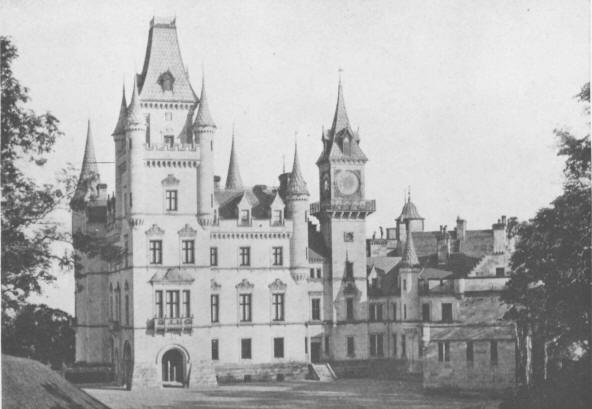

Brora — Dunrobin Castle — Golspie ¶ The Mound — Loch Buidhee — Bonar

Bridge — Dornoch Firth — Half-way House [Aultnamain Inn] ¶ Novar —

Cromarty Firth — Dingwall — Muir of Ord — Beauly — Bogroy Inn —

Inverness ¶¶

SECOND WEEK'S JOURNEY — Sept. 25 to Oct. 1.

Tomnahurich — Loch Ness — Caledonian Canal — Drumnadrochit ¶

Urquhart Castle — Invermoriston — Glenmoriston — Fort Augustus —

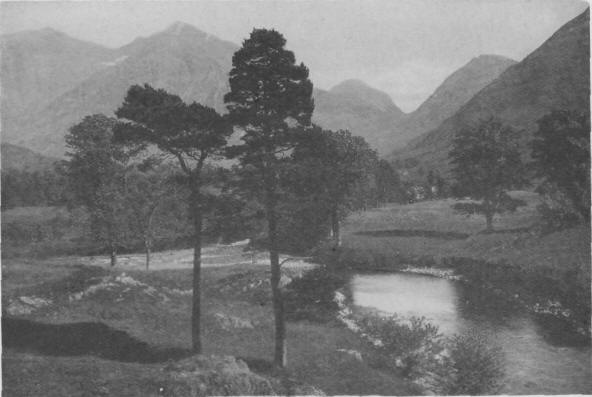

Invergarry ¶ Glengarry — Well of the Heads — Loggan Bridge — Loch

Lochy — Spean Bridge — Fort William ¶ Inverlochy Castle — Ben Nevis

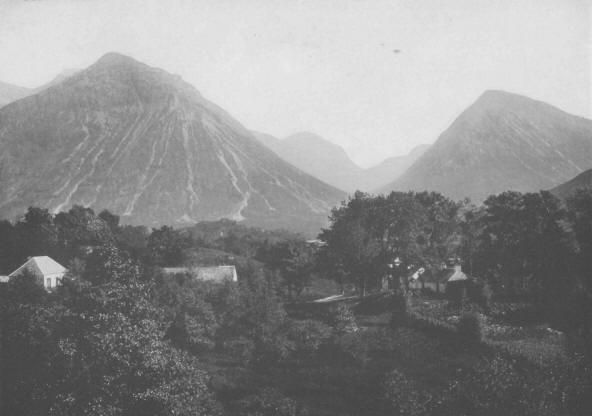

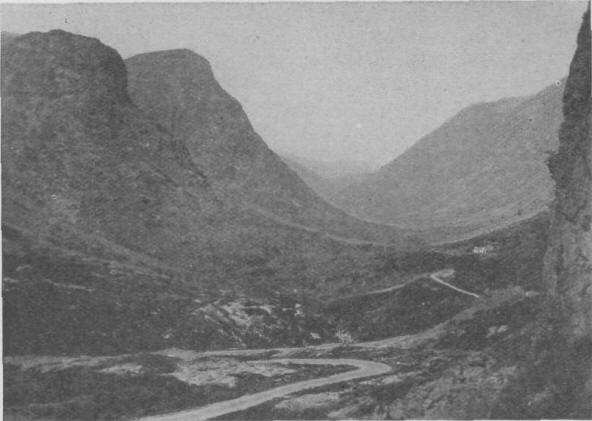

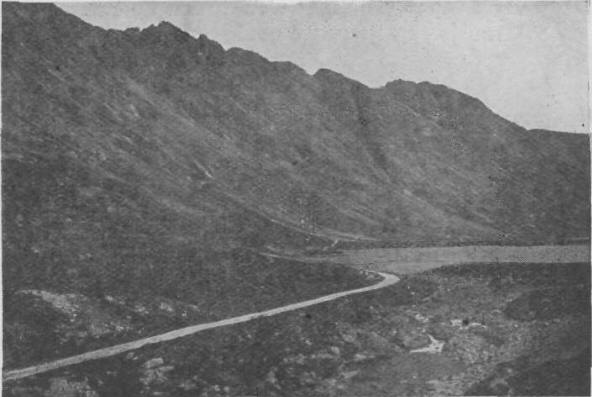

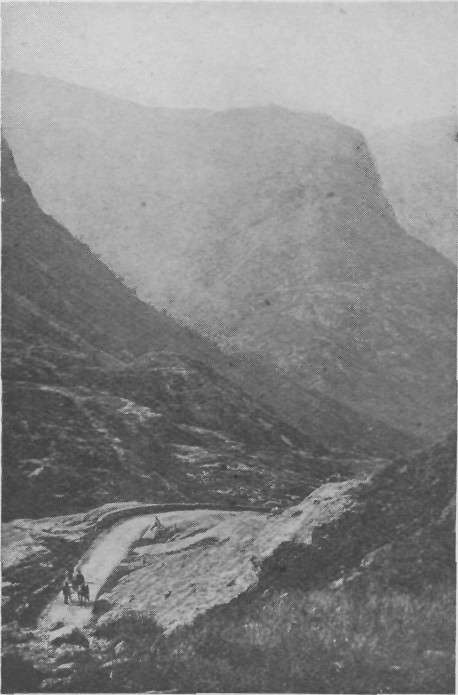

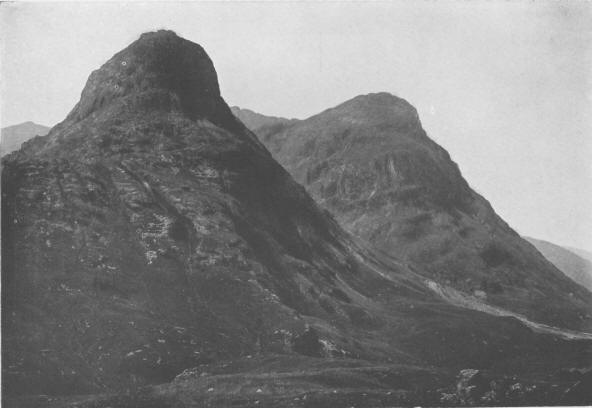

— Fort William ¶ Loch Linnhe — Loch Leven — Devil's Stair — Pass of

Glencoe — Clachaig Inn ¶ Glencoe Village — Ballachulish — Kingshouse

— Inveroran — Loch Tulla — Bridge of Orchy — Glen Orchy ¶ Dalmally

¶¶

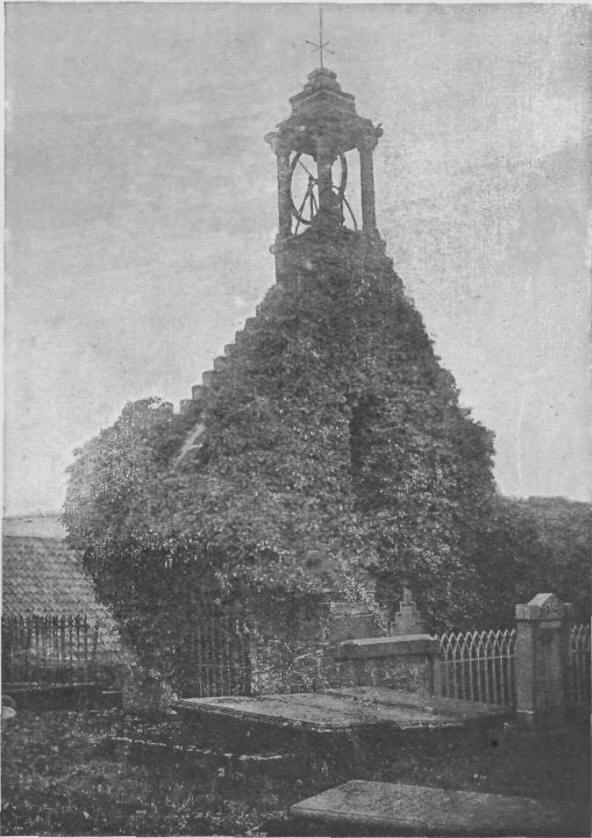

THIRD WEEK'S JOURNEY — Oct. 2 to Oct. 8.

Loch Awe — Cruachan Mountain — Glen Aray — Inverary Castle —

Inverary — Loch Fyne — Cairndow Inn ¶ Glen Kinglas — Loch Restil —

Rest and be Thankful — Glen Croe — Ben Arthur — Loch Long — Arrochar

— Tarbet — Loch Lomond — Luss — Helensburgh ¶ The Clyde — Dumbarton

— Renton — Alexandria — Balloch — Kilmaronock — Drymen ¶ Buchlyvie —

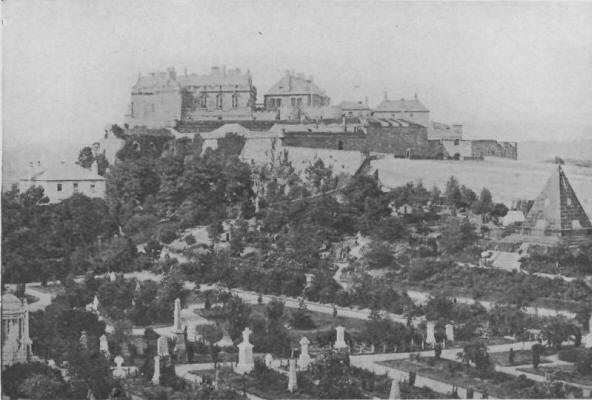

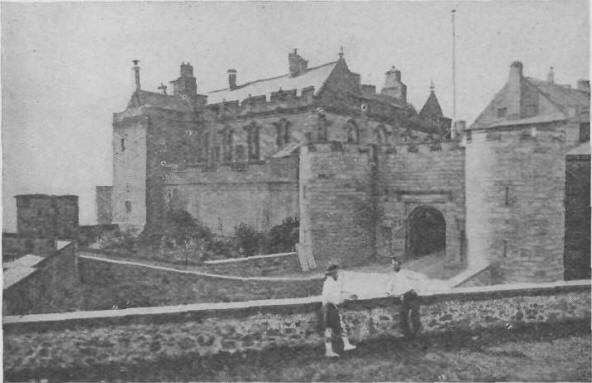

Kippen — Gargunnock — Windings of the Forth — Stirling ¶ Wallace

Monument — Cambuskenneth — St. Ninians — Bannockburn — Carron —

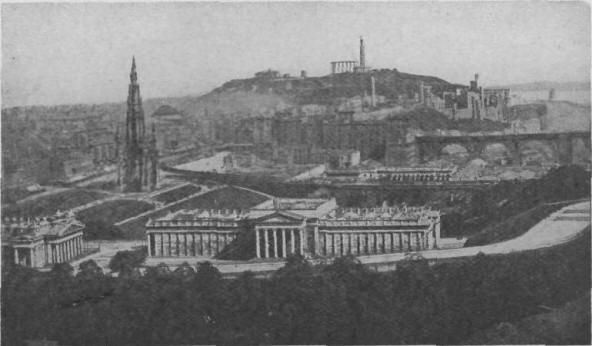

Falkirk ¶ Laurieston — Polmont — Linlithgow — Edinburgh ¶¶

FOURTH WEEK'S JOURNEY — Oct. 9 to Oct. 15.

Craigmillar — Rosslyn — Glencorse — Penicuik — Edleston — Cringletie

— Peebles ¶ River Tweed — Horsburgh — Innerleithen — Traquair —

Elibank Castle — Galashiels — Abbotsford — Melrose — Lilliesleaf ¶

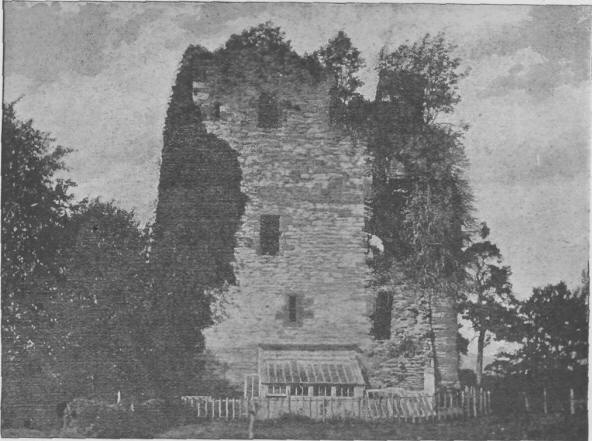

Teviot Dale — Hassendean — Minto — Hawick — Goldielands Tower —

Branxholm Tower — Teviothead — Caerlanrig — Mosspaul Inn — Langholm

— Gilnockie Tower — Canonbie Colliery ¶ River Esk — "Cross Keys Inn"

— Scotch Dyke — Longtown ¶ Solway Moss — River Sark — Springfield —

Gretna Green — Todhills — Kingstown — Carlisle — Wigton — Aspatria ¶

Maryport — Cockermouth — Bassenthwaite Lake — Portinscale — Keswick

¶¶

FIFTH WEEK'S JOURNEY — Oct 16 to Oct. 22.

Falls of Lodore — Derwentwater — Bowder Stone — Borrowdale — Green

Nip — Wythburn — Grasmere ¶ Rydal — Ambleside — Windermere —

Hawkshead — Coniston — Ulverston ¶ Dalton-in-Furness — Furness Abbey

— Barrow Monument — Haverthwaite ¶ Newby Bridge — Cartmel Fell —

Kendal ¶ Kirkby Lonsdale — Devil's Bridge — Ingleton — Giggleswick —

Settle — Malham ¶ Malham Cove — Gordale Scar — Kilnsey — River

Wharfe — Grassington — Greenhow — Pateley Bridge ¶¶

SIXTH WEEK'S JOURNEY — Oct. 23 to Oct. 29.

Brimham Rocks — Fountains Abbey — Ripon — Boroughbridge — Devil's

Arrows — Aldeborough ¶ Marston Moor — River Ouse — York ¶ Tadcaster

— Towton Field — Sherburn-in-Elmet — River Aire — Ferrybridge —

Pontefract ¶ Robin Hood's Well — Doncaster ¶ Conisborough —

Rotherham ¶ Attercliffe Common — Sheffield — Norton — Hathersage —

Little John's Grave — Castleton ¶¶

SEVENTH WEEK'S JOURNEY — Oct. 30 to Nov. 5.

Castleton — Tideswell — Miller's Dale — Flagg Moor — Newhaven —

Tissington — Ashbourne ¶ River Dove — Mayfield — Ellastone — Alton

Towers — Uttoxeter — Bagot's Wood — Needwood Forest — Abbots Bromley

— Handsacre ¶ Lichfield — Tamworth — Atherstone — Watling Street —

Nuneaton ¶ Watling Street — High Cross — Lutterworth — River Swift —

Fosse Way — Brinklow — Coventry ¶ Kenilworth — Leamington —

Stoneleigh Abbey — Warwick — Stratford-on-Avon — Charlecote Park —

Kineton — Edge Hill ¶ Banbury — Woodstock — Oxford ¶¶

EIGHTH WEEK'S JOURNEY — Nov. 6 to Nov. 12.

Oxford — Sunningwell — Abingdon — Vale of White Horse — Wantage —

Icknield Way — Segsbury Camp — West Shefford — Hungerford ¶

Marlborough Downs — Miston — Salisbury Plain — Stonehenge — Amesbury

— Old Sarum — Salisbury ¶ Wilton — Compton Chamberlain — Shaftesbury

— Blackmoor Vale — Sturminster ¶ Blackmoor Vale — Cerne Abbas —

Charminster — Dorchester — Bridport ¶ The Chesil Bank — Chideoak —

Charmouth — Lyme Regis — Axminster — Honiton — Exeter ¶ Exminster —

Star Cross — Dawlish — Teignmouth — Torquay ¶¶

NINTH WEEK'S JOURNEY — Nov. 13 to Nov. 18.

Torbay — Cockington — Compton Castle — Marldon — Berry Pomeroy —

River Dart — Totnes — Sharpham — Dittisham — Dartmouth — Totnes ¶

Dartmoor — River Erme — Ivybridge — Plymouth ¶ Devonport — St.

Budeaux — Tamerton Foliot — Buckland Abbey — Walkhampton — Merridale

— River Tavy — Tavistock — Hingston Downs — Callington — St. Ive —

Liskeard ¶ St. Neot — Restormel Castle — Lostwithiel — River Fowey —

St. Blazey — St. Austell — Truro ¶ Perranarworthal — Penryn —

Helston — The Lizard — St. Breage — Perran Downs — Marazion — St.

Michael's Mount — Penzance ¶ Newlyn — St. Paul — Mousehole — St.

Buryan — Treryn — Logan Rock — St. Levan — Tol-Peden-Penwith —

Sennen — Land's End — Penzance ¶¶

HOMEWARD BOUND — Nov. 20 and 21.

HOW WE GOT TO JOHN O' GROAT'S

Thursday, September 7th.

It was one o'clock in the morning when we started on the

three-mile walk to Warrington, where we were to join the 2.18 a.m. train

for Glasgow, and it was nearly ten o'clock when we reached that town,

the train being one hour and twenty minutes late. This delay caused us

to be too late for the steamboat by which we intended to continue our

journey further north, and we were greatly disappointed in having thus

early in our journey to abandon the pleasant and interesting sail down

the River Clyde and on through the Caledonian Canal. We were, therefore,

compelled to alter our route, so we adjourned to the Victoria Temperance

Hotel for breakfast, where we were advised to travel to Aberdeen by

train, and thence by steamboat to Wick, the nearest available point to

John o' Groat's.

We had just time to inspect Sir Walter Scott's monument

that adorned the Square at Glasgow, and then we left by the 12.35 train

for Aberdeen. It was a long journey, and it was half-past eight o'clock

at night before we reached our destination, but the weariness of

travelling had been whiled away by pleasant company and delightful

scenery.

We had travelled continuously for about 360 miles, and we

were both sleepy and tired as we entered Forsyth's Hotel to stay the

night.

Friday, September 8th.

After a good night's rest, followed by a good breakfast,

we went out to inquire the time our boat would leave, and, finding it

was not due away until evening, we returned to the hotel and refreshed

ourselves with a bath, and then went for a walk to see the town of

Aberdeen, which is mostly built of the famous Aberdeen granite. The

citizens were quite proud of their Union Street, the main thoroughfare,

as well they might be, for though at first sight we thought it had

rather a sombre appearance, yet when the sky cleared and the sun shone

out on the golden letters that adorned the buildings we altered our

opinion, for then we saw the "Granite City" at its best.

We spent the time rambling along the beach, and, as

pleasure seekers generally do, passed the day comfortably, looking at

anything and everything that came in our way. By no means sea-faring

men, having mainly been accustomed to village life, we had some

misgivings when we boarded the s.s. St.

Magnus at eight o'clock

in the evening, and our sensations during the night were such as are

common to what the sailors call "land-lubbers." We were fortunate,

however, in forming the acquaintance of a lively young Scot, who was

also bound for Wick, and who cheered us during the night by giving us

copious selections from Scotland's favourite bard, of whom he was

greatly enamoured. We heard more of "Rabbie Burns" that night than we

had ever heard before, for our friend seemed able to recite his poetry

by the yard and to sing some of it also, and he kept us awake by

occasionally asking us to join in the choruses. Some of the sentiments

of Burns expressed ideals that seem a long time in being realised, and

one of his favourite quotations, repeated several times by our friend,

dwells in our memory after many years:

For a' that an' a' that

It's coming, yet, for a' that,

That man to man the war-ld o'er

Shall brithers be for a' that.

During the night, as the St.

Magnus ploughed her way

through the foaming billows, we noticed long, shining streaks on the

surface of the water, varying in colour from a fiery red to a silvery

white, the effect of which, was quite beautiful. Our friend informed us

these were caused by the stampede of the shoals of herrings through

which we were then passing.

The herring fishery season was now on, and, though we

could not distinguish either the fishermen or their boats when we passed

near one of their fishing-grounds, we could see the lights they carried

dotted all over the sea, and we were apprehensive lest we should collide

with some of them, but the course of the St.

Magnus had evidently been

known and provided for by the fishermen.

We had a long talk with our friend about our journey

north, and, as he knew the country well, he was able to give us some

useful information and advice. He told us that if we left the boat at

Wick and walked to John o' Groat's from there, we should have to walk

the same way back, as there was only the one road, and if we wished to

avoid going over the same ground twice, he would advise us to remain on

the St. Magnus until

she reached her destination, Lerwick, in the Shetland Islands, and the

cost by the boat would be very little more than to Wick. She would only

stay a short time at Lerwick, and then we could return in her to

Kirkwall, in the Orkney Islands. From that place we could walk across

the Mainland to Stromness, where we should find a small steamboat which

conveyed mails and passengers across the Pentland Firth to Thurso in the

north of Scotland, from which point John o' Groat's could easily be

reached, and, besides, we might never again have such a favourable

opportunity of seeing the fine rock scenery of those northern islands.

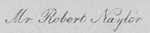

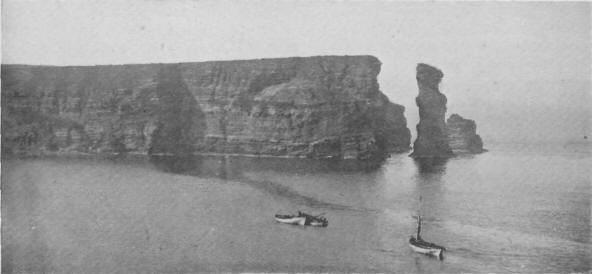

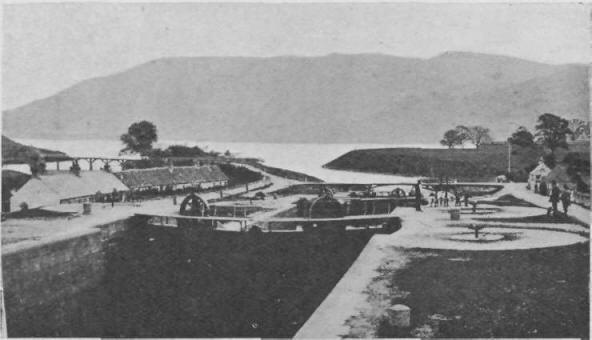

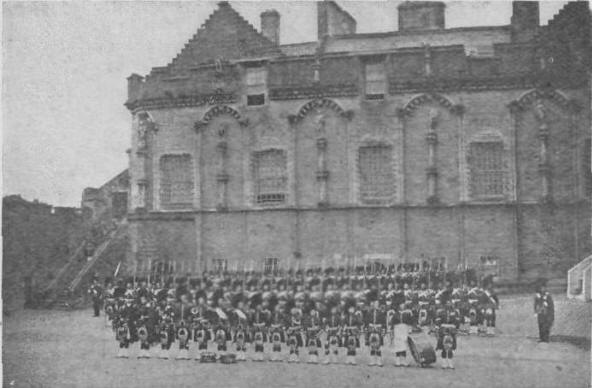

WICK HARBOUR.

From a photograph taken in 1867.

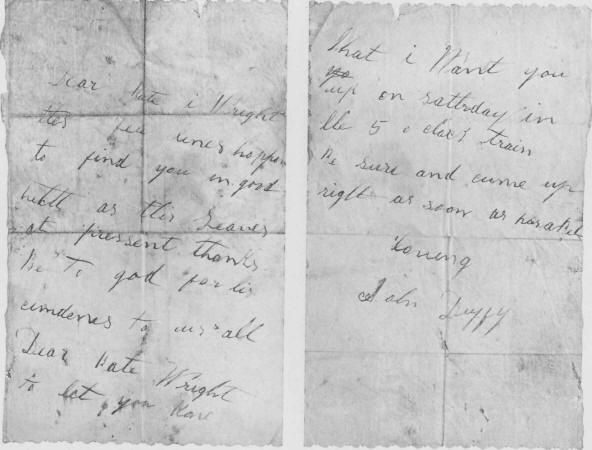

We were delighted with his suggestion, and wrote a

hurried letter home advising our people there of this addition to our

journey, and our friend volunteered to post the letter for us at Wick.

It was about six o'clock in the morning when we neared that important

fishery town and anchored in the harbour, where we had to stay an hour

or two to load and unload cargo. Our friend the Scot had to leave us

here, but we could not allow him to depart without some kind of ceremony

or other, and as the small boat came in sight that was to carry him

ashore, we decided to sing a verse or two of "Auld Lang Syne" from his

favourite poet Burns; but my brother could not understand some of the

words in one of the verses, so he altered and anglicised them slightly:

An' here's a haund, my trusty friend,

An' gie's a haund o' thine;

We'll tak' a cup o' kindness

yet,

For the sake o' auld lang

syne.

Some of the other passengers joined in the singing, but

we never realised the full force of this verse until we heard it sung in

its original form by a party of Scots, who, when they came to this

particular verse, suited the action to the word by suddenly taking hold

of each other's hands, thereby forming a cross, and meanwhile beating

time to the music. Whether the cross so formed had any religious

significance or not, we did not know.

Our friend was a finely built and intelligent young man,

and it was with feelings of great regret that we bade him farewell and

watched his departure over the great waves, with the rather mournful

presentiment that we were being parted from him for ever!

Saturday, September 9th.

There were signs of a change in the weather as we left

Wick, and the St. Magnus rolled

considerably; but occasionally we had a good view of the precipitous

rocks that lined the coast, many of them having been christened by the

sailors after the objects they represented, as seen from the sea. The

most prominent of these was a double-headed peak in Caithness, which

formed a remarkably perfect resemblance to the breasts of a female giant

with nipples complete, and this they had named the "Maiden's Paps." Then

there was the "Old Man of Hoy," and other rocks that stood near the

entrance to that terrible torrent of the sea, the Pentland Firth; but,

owing to the rolling of our ship, we were not in a fit state either of

mind or body to take much interest in them, and we were very glad when

we reached the shelter of the Orkney Islands and entered the fine

harbour of Kirkwall. Here we had to stay for a short time, so we went

ashore and obtained a substantial lunch at the Temperance Hotel near the

old cathedral, wrote a few letters, and at 3 p.m. rejoined the St.

Magnus.

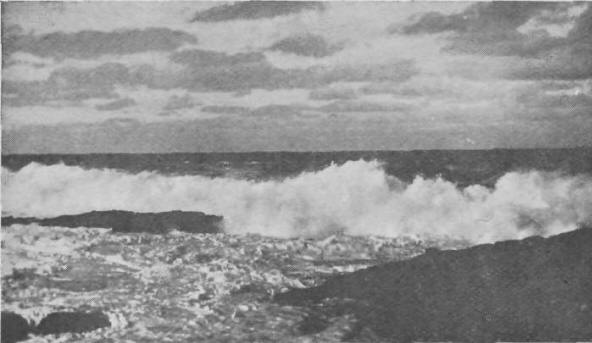

The sea had been quite rough enough previously, but it

soon became evident that it had been smooth compared with what followed,

and during the coming night we wished many times that our feet were once

more on terra firma.

The rain descended, the wind increased in violence, and the waves rolled

high and broke over the ship, and we were no longer allowed to occupy

our favourite position on the upper deck, but had to descend a stage

lower. We were saturated with water from head to foot in spite of our

overalls, and we were also very sick, and, to add to our misery, we

could hear, above the noise of the wind and waves, the fearful groaning

of some poor woman who, a sailor told us, had been suddenly taken ill,

and it was doubtful if she could recover. He carried a fish in his hand

which he had caught as it was washed on deck, and he invited us to come

and see the place where he had to sleep. A dismal place it was too,

flooded with water, and not a dry thing for him to put on. We could not

help feeling sorry that these sailors had such hardships to undergo; but

he seemed to take it as a matter of course, and appeared to be more

interested in the fish he carried than in the storm that was then

raging. We were obliged to keep on the move to prevent our taking cold,

and we realised that we were in a dark, dismal, and dangerous position,

and thought of the words of a well-known song and how appropriate they

were to that occasion:

"O Pilot! 'tis a fearful night,

There's danger on the deep;

I'll come and pace the deck

with thee,

"Go down!" the Pilot cried,

"go down!

This is no place for thee;

Fear not! but trust in

Providence,

Wherever thou may'st be."

The storm continued for hours, and, as it gradually

abated, our feelings became calmer, our fears subsided, and we again

ventured on the upper deck. The night had been very dark hitherto, but

we could now see the occasional glimmering of a light a long distance

ahead, which proved to be that of a lighthouse, and presently we could

distinguish the bold outlines of the Shetland Islands.

As we entered Bressay Sound, however, a beautiful

transformation scene suddenly appeared, for the clouds vanished as if by

magic, and the last quarter of the moon, surrounded by a host of stars,

shone out brilliantly in the clear sky. It was a glorious sight, for we

had never seen these heavenly bodies in such a clear atmosphere before,

and it was hard to realise that they were so far away from us. We could

appreciate the feelings of a little boy of our acquaintance, who, when

carried outside the house one fine night by his father to see the moon,

exclaimed in an ecstasy of delight: "Oh, reach it, daddy!—reach it!" and

it certainly looked as if we could have reached it then, so very near

did it appear to us.

It was two o'clock on Sunday morning, September 10th,

when we reached Lerwick, the most northerly town in Her Majesty's

British Dominions, and we appealed to a respectable-looking passenger

who was being rowed ashore with us in the boat as to where we could

obtain good lodgings. He kindly volunteered to accompany us to a house

at which he had himself stayed before taking up his permanent residence

as a tradesman in the town and which he could thoroughly recommend.

Lerwick seemed a weird-looking place in the moonlight, and we turned

many corners on our way to our lodgings, and were beginning to wonder

how we should find our way out again, when our companion stopped

suddenly before a private boarding-house, the door of which was at once

opened by the mistress. We thanked the gentleman for his kind

introduction, and as we entered the house the lady explained that it was

her custom to wait up for the arrival of the St.

Magnus. We found the fire burning and the kettle boiling, and the

cup that cheers was soon on the table with the usual accompaniments,

which were quickly disposed of. We were then ushered to our apartments

—a bedroom and sitting or dining-room combined, clean and comfortable,

but everything seemed to be moving like the ship we had just left. Once

in bed, however, we were soon claimed by the God of Slumber, sleep, and

dreams—our old friend Morpheus.

Sunday, September 10th.

In the morning we attended the English Episcopalian

Church, and, after service, which was rather of a high church character,

we walked into the country until we came in sight of the rough square

tower of Scalloway Castle, and on our return we inspected the ruins of a

Pictish castle, the first of the kind we had seen, although we were

destined to see many others in the course of our journey.

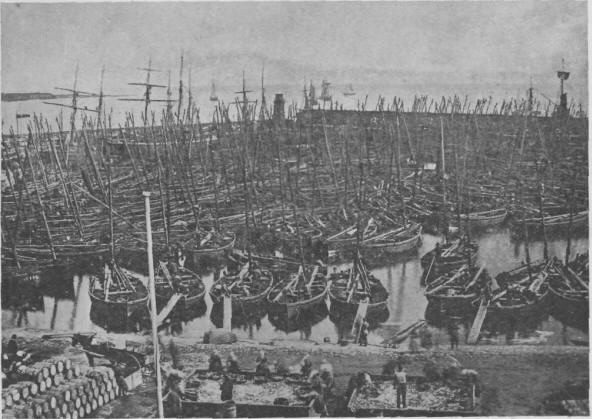

LERWICK.

Commercial Street as it was in 1871.

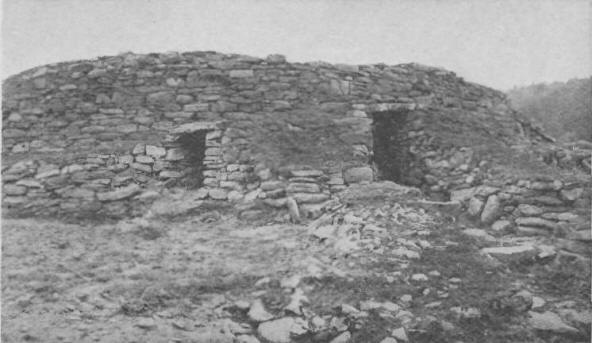

The Picts, we were informed, were a race of people who

settled in the north of Scotland in pre-Roman times, and who constructed

their dwellings either of earth or stone, but always in a circular form.

This old castle was built of stone, and the walls were five or six yards

thick; inside these walls rooms had been made for the protection of the

owners, while the circular, open space enclosed by the walls had

probably been for the safe housing of their cattle. An additional

protection had also been formed by the water with which the castle was

surrounded, and which gave it the appearance of a small island in the

middle of a lake. It was connected with the land by means of a narrow

road, across which we walked. The castle did not strike us as having

been a very desirable place of residence; the ruins had such a very

dismal and deserted appearance that we did not stay there long, but

returned to our lodgings for lunch. After this we rested awhile, and

then joined the townspeople, who were patrolling every available space

outside. The great majority of these were women, healthy and

good-looking, and mostly dressed in black, as were also those we

afterwards saw in the Orkneys and the extreme north of Scotland, and we

thought that some of our disconsolate bachelor friends might have been

able to find very desirable partners for life in these northern

dominions of Her Majesty the Queen.

The houses in Lerwick had been built in all sorts of

positions without any attempt at uniformity, and the rough, flagged

passage which did duty for the main street was, to our mind, the

greatest curiosity of all, and almost worth going all the way to

Shetland to see. It was curved and angled in such an abrupt and zigzag

manner that it gave us the impression that the houses had been built

first, and the street, where practicable, filled in afterwards. A

gentleman from London was loud in his praise of this wonderful street;

he said he felt so much safer there than in "beastly London," as he

could stand for hours in that street before the shop windows without

being run over by any cab, cart, or omnibus, and without feeling a

solitary hand exploring his coat pockets. This was quite true, as we did

not see any vehicles in Lerwick, nor could they have passed each other

through the crooked streets had they been there, and thieves would have

been equally difficult to find. Formerly, however, Lerwick had an evil

reputation in that respect, as it was noted for being the abode of

sheep-stealers and pirates, so much so, that, about the year 1700, it

had become such a disreputable place that an earnest appeal was made to

the "Higher Authorities" to have the place burnt, and for ever made

desolate, on account of its great wickedness. Since that time, however,

the softening influences of the Christian religion had permeated the

hearts of the people, and, at the time of our visit, the town was well

supplied with places of worship, and it would have been difficult to

have found any thieves there then. We attended evening service in the

Wesleyan Chapel, where we found a good congregation, a well-conducted

service, and an acceptable preacher, and we reflected that Mr. Wesley

himself would have rejoiced to know that even in such a remote place as

Lerwick his principles were being promulgated.

Monday, September 11th.

We rose early with the object of seeing all we could in

the short time at our disposal, which was limited to the space of a

single day, or until the St.

Magnus was due out in the

evening on her return journey. We were anxious to see a large cavern

known as the Orkneyman's Cave, but as it could only be reached from the

sea, we should have had to engage a boat to take us there. We were told

the cave was about fifty feet square at the entrance, but immediately

beyond it increased to double the size; it was possible indeed to sail

into it with a boat and to lose sight of daylight altogether.

The story goes that many years ago an Orkneyman was

pursued by a press-gang, but escaped being captured by sailing into the

cave with his boat. He took refuge on one of the rocky ledges inside,

but in his haste he forgot to secure his boat, and the ground swell of

the sea washed it out of the cave. To make matters worse, a storm came

on, and there he remained a prisoner in the cave for two days; but as

soon as the storm abated he plunged into the water, swam to a small rock

outside, and thence climbed to the top of the cliff and so escaped.

Since that event it had been known as the Orkneyman's Cave.

We went to the boat at the appointed time, but

unfortunately the wind was too strong for us to get round to the cave,

so we were disappointed. The boatman suggested as the next best thing

that we should go to see the Island of Noss. He accordingly took us

across the bay, which was about a mile wide, and landed us on the Island

of Bressay. Here it was necessary for us to get a permit to enable us to

proceed farther, so, securing his boat, the boatman accompanied us to

the factor's house, where he procured a pass, authorising us to land on

the Island of Noss, of which the following is a facsimile:

Allow Mr. Nailer and friends

to land on Noss.

To Walter. A.M. Walker.

Here he left us, as we had to walk across the Island of

Bressay, and, after a tramp of two or three miles, during which we did

not see a single human being, we came to another water where there was a

boat. Here we found Walter, and, after we had exhibited our pass, he

rowed us across the narrow arm of the sea and landed us on the Island of

Noss. He gave us careful instructions how to proceed so that we could

see the Holm of Noss, and warned us against approaching too near the

edge of the precipice which we should find there. After a walk of about

a mile, all up hill, we came to the precipitous cliffs which formed the

opposite boundary of the island, and from a promontory there we had a

magnificent view of the rocks, with the waves of the sea dashing against

them, hundreds of feet below. A small portion of the island was here

separated from the remainder by a narrow abyss about fifty feet wide,

down which it was terrible to look, and this separated portion was known

as the Holm of Noss. It rose precipitously on all sides from the sea,

and its level surface on the top formed a favourite nesting-place for

myriads of wild birds of different varieties, which not only covered the

top of the Holm, but also the narrow ledges along its jagged sides.

Previous to the seventeenth century, this was one of the places where

the foot of man had never trod, and a prize of a cow was offered to any

man who would climb the face of the cliff and establish a connection

with the mainland by means of a rope, as it was thought that the Holm

would provide pasturage for about twenty sheep. A daring fowler, from

Foula Island, successfully performed the feat, and ropes were firmly

secured to the rocks on each side, and along two parallel ropes a box or

basket was fixed, capable of holding a man and a sheep. This apparatus

was named the Cradle of Noss, and was so arranged that an Islander with

or without a sheep placed in the cradle could drag himself across the

chasm in either direction. Instead, however, of returning by the rope or

cradle, on which he would have been comparatively safe, the hardy fowler

decided to go back by the same way he had come, and, missing his

foothold, fell on the rocks in the sea below and was dashed to pieces,

so that the prize was never claimed by him.

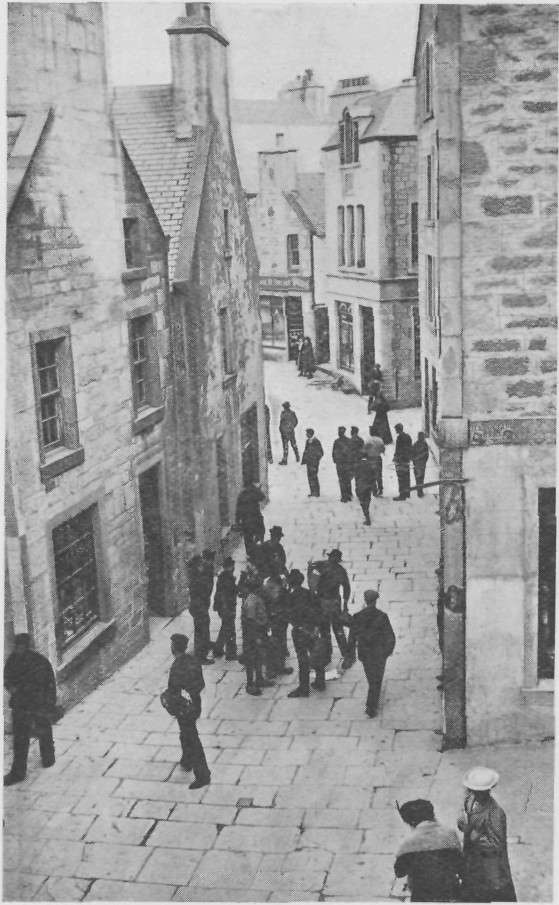

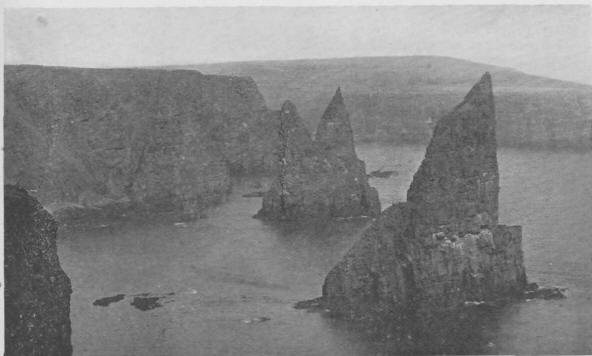

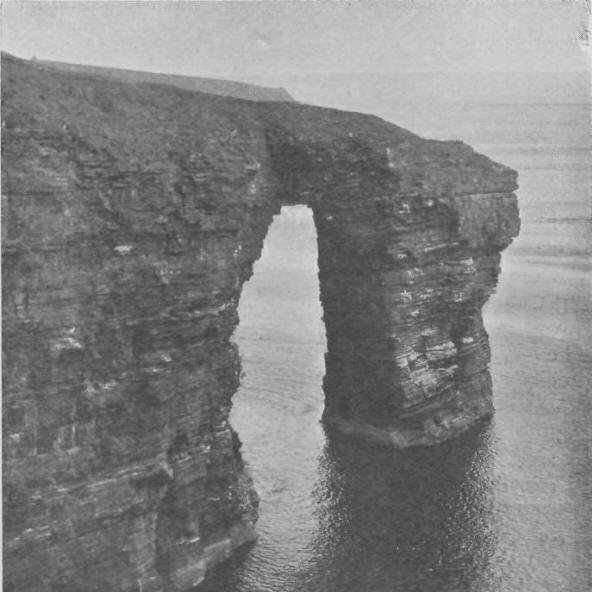

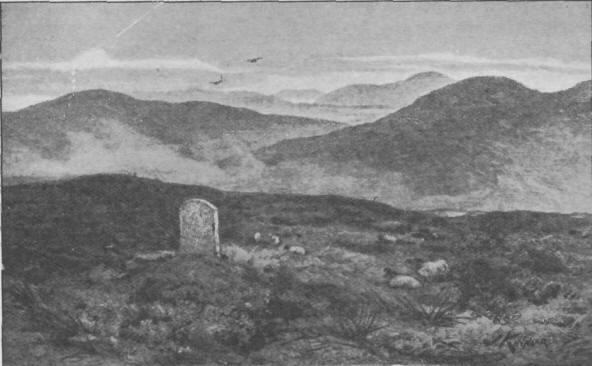

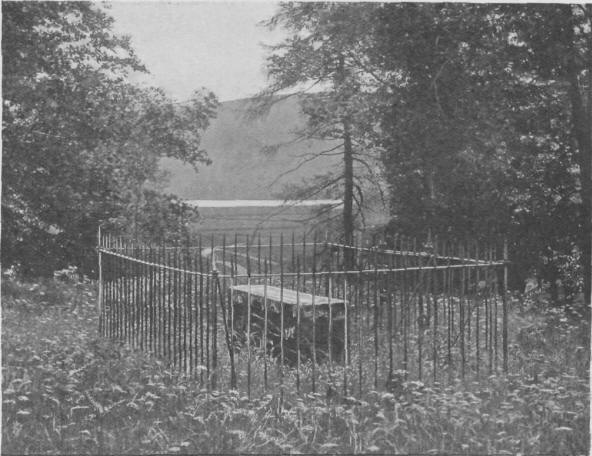

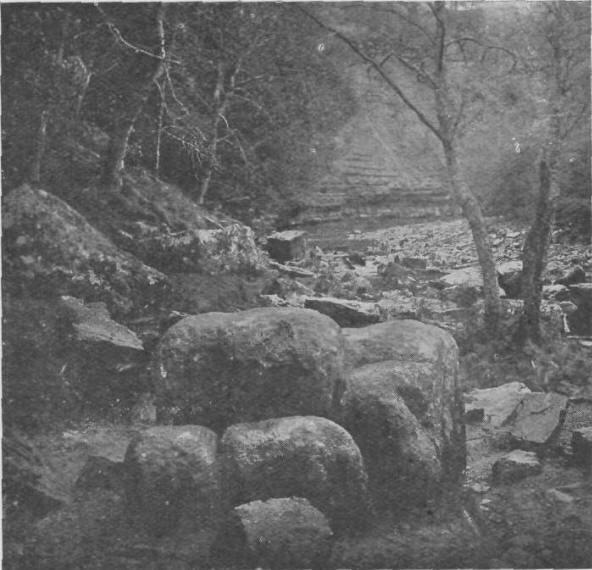

THE HOLM OF NOSS.

"It made us shudder ... as we peered down on the abysmal depths below."

We felt almost spellbound as we approached this awful

chasm, and as if we were being impelled by some invisible force towards

the edge of the precipice. It fairly made us shudder as on hands and

knees we peered down on the abysmal depths below. It was a horrible

sensation, and one that sometimes haunted us in our dreams for years

afterwards, and we felt greatly relieved when we found that we could

safely crawl away and regain an upright posture. We could see thousands

upon thousands of wild birds, amongst which the ordinary sea-gull was

largely represented; but there were many other varieties of different

colours, and the combination of their varied cries, mingled with the

bleating of the sheep, the whistling of the wind, the roaring of the

waves as they dashed against the rocks below, or entered the caverns

with a sound like distant thunder, tended to make us feel quite

bewildered. We retired to the highest elevation we could find, and

there, 600 miles from home, and perhaps as many feet above sea-level,

was solitude in earnest. We were the only human beings on the island,

and the enchanting effect of the wild scenery, the vast expanse of sea,

the distant moaning of the waters, the great rocks worn by the wind and

the waves into all kinds of fantastic shapes and caverns, the blue sky

above with the glorious sun shining upon us, all proclaimed to our minds

the omnipotence of the great Creator of the Universe, the Almighty Maker

and Giver of all.

We lingered as long as we could in these lonely and

romantic solitudes, and, as we sped down the hill towards the boat, we

suddenly became conscious that we had not thought either of what we

should eat or what we should drink since we had breakfasted early in the

morning, and we were very hungry. Walter was waiting for us on our side

of the water, as he had been watching for our return, and had seen us

coming when we were nearly a mile away. There was no vegetation to

obstruct the view, for, as he said, we might walk fifty miles in

Shetland without meeting with a bush or tree. We had an agreeable

surprise when we reached the other side of the water in finding some

light refreshments awaiting our arrival which he had thoughtfully

provided in the event of their being required, and for which we were

profoundly thankful. The cradle of Noss had disappeared some time before

our visit, but, if it had been there, we should have been too terrified

to make use of it. It had become dangerous, and as the pasturage of

sheep on the Holm had proved a failure, the birds had again become

masters of the situation, while the cradle had fallen to decay. Walter

gave us an awful description of the danger of the fowler's occupation,

especially in the Foula Island, where the rocks rose towering a thousand

feet above the sea. The top of the cliffs there often projected over

their base, so that the fowler had to be suspended on a rope fastened to

the top of the cliff, swinging himself backwards and forwards like a

pendulum until he could reach the ledge of rock where the birds laid

their eggs. Immediately he landed on it, he had to secure his rope, and

then gather the eggs in a hoop net, and put them in his wallet, and then

swing off again, perhaps hundreds of feet above the sea, to find another

similar ledge, so that his business was practically carried on in the

air. On one of these occasions a fowler had just reached a landing-place

on the precipice, when his rope slipped out of his hand, and swung away

from the cliff into the empty air. If he had hesitated one moment, he

would have been lost for ever, as in all probability he would either

have been starved to death on the ledge of rock on which he was or

fallen exhausted into the sea below. The first returning swing of the

rope might bring him a chance of grasping it, but the second would be

too far away. The rope came back, the desperate man measured the

distance with his eye, sprang forward in the air, grasped the rope, and

was saved.

Sometimes the rope became frayed or cut by fouling some

sharp edge of rock above, and, if it broke, the fowler was landed in

eternity. Occasionally two or three men were suspended on the same rope

at the same time. Walter told us of a father and two sons who were on

the rope in this way, the father being the lowest and his two sons being

above him, when the son who was uppermost saw that the rope was being

frayed above him, and was about to break. He called to his brother who

was just below that the rope would no longer hold them all, and asked

him to cut it off below him and let their father go. This he indignantly

refused to do, whereupon his brother, without a moment's hesitation, cut

the rope below himself, and both his father and brother perished.

It was terrible to hear such awful stories, as our nerves

were unstrung already, so we asked our friend Walter not to pile on the

agony further, and, after rewarding him for his services, we hurried

over the remaining space of land and sea that separated us from our

comfortable quarters at Lerwick, where a substantial tea was awaiting

our arrival.

We were often asked what we thought of Shetland and its

inhabitants.

Shetland was fine in its mountain and coast scenery, but

it was wanting in good roads and forests, and it seemed strange that no

effort had been made to plant some trees, as forests had formerly

existed there, and, as a gentleman told us, there seemed no peculiarity

in either the soil or climate to warrant an opinion unfavourable to the

country's arboricultural capacity. Indeed, such was the dearth of trees

and bushes, that a lady, who had explored the country thoroughly,

declared that the tallest and grandest tree she saw during her visit to

the Islands was a stalk of rhubarb which had run to seed and was waving

its head majestically in a garden below the old fort of Lerwick!

Agriculture seemed also to be much neglected, but

possibly the fishing industry was more profitable. The cottages also

were very small and of primitive construction, many of them would have

been condemned as being unfit for human habitation if they had existed

elsewhere, and yet, in spite of this apparent drawback, these hardy

islanders enjoyed the best of health and brought up large families of

very healthy-looking children. Shetland will always have a pleasant

place in our memories, and, as regards the people who live there, to

speak the truth we scarcely ever met with folks we liked better. We

received the greatest kindness and hospitality, and met with far greater

courtesy and civility than in the more outwardly polished and

professedly cultivated parts of the countries further south, especially

when making inquiries from people to whom we had not been "introduced"!

The Shetlanders spoke good English, and seemed a highly intelligent race

of people. Many of the men went to the whale and other fisheries in the

northern seas, and "Greenland's icy mountains" were well known to them.

On the island there were many wives and mothers who

mourned the loss of husbands and sons who had perished in that dangerous

occupation, and these remarks also applied to the Orkney Islands, to

which we were returning, and might also account for so many of these

women being dressed in black. Every one told us we were visiting the

islands too late in the year, and that we ought to have made our

appearance at an earlier period, when the sun never sets, and when we

should have been able to read at midnight without the aid of an

artificial light. Shetland was evidently in the range of the "Land of

the Midnight Sun," but whether we should have been able to keep awake in

order to read at midnight was rather doubtful, as we were usually very

sleepy. At one time of the year, however, the sun did not shine at all,

and the Islanders had to rely upon the Aurora Borealis, or the Northern

Lights, which then made their appearance and shone out brilliantly,

spreading a beautifully soft light over the islands. We wondered if it

were this or the light of the midnight sun that inspired the poet to

write:

Night walked in beauty o'er the peaceful sea.

Whose gentle waters spoke

tranquillity,

or if it had been borrowed from some more peaceful clime,

as we had not yet seen the "peaceful sea" amongst these northern

islands. We had now once more to venture on its troubled waters, and we

made our appearance at the harbour at the appointed time for the

departure of theSt. Magnus. We were, however, informed that the

weather was too misty for our boat to leave, so we returned to our

lodgings, ordered a fire, and were just making ourselves comfortable and

secretly hoping our departure might be delayed until morning, when Mrs.

Sinclair, our landlady, came to tell us that the bell, which was the

signal for the St. Magnus to

leave, had just rung. We hurried to the quay, only to find that the boat

which conveyed passengers and mails to our ship had disappeared. We were

in a state of consternation, but a group of sailors, who were standing

by, advised us to hire a special boat, and one was brought up

immediately, by which, after a lot of shouting and whistling—for we

could scarcely see anything in the fog—we were safely landed on the

steamboat. We had only just got beyond the harbour, however, when the

fog became so dense that we suddenly came to a standstill, and had to

remain in the bay for a considerable time. When at last we moved slowly

outwards, the hoarse whistle of the St.

Magnus was sounded at

short intervals, to avoid collision with any other craft. It had a

strangely mournful sound, suggestive of a funeral or some great

calamity, and we should almost have preferred being in a storm, when we

could have seen the danger, rather than creeping along in the fog and

darkness, with a constant dread of colliding with some other boat or

with one of the dangerous rocks which we knew were in the vicinity.

Sleep was out of the question until later, when the fog began to clear a

little, and, in the meantime, we found ourselves in the company of a

group of young men who told us they were going to Aberdeen.

One of them related a rather sorrowful story. He and his

mates had come from one of the Shetland Islands from which the

inhabitants were being expelled by the factor, so that he could convert

the whole of the island into a sheep farm for his own personal

advantage. Their ancestors had lived there from time immemorial, but

their parents had all received notice to leave, and other islands were

being depopulated in the same way. The young men were going to Aberdeen

to try to find ships on which they could work their passage to some

distant part of the world; they did not know or care where, but he said

the time would come when this country would want soldiers and sailors,

and would not be able to find them after the men had been driven abroad.

He also told us about what he called the "Truck System," which was a

great curse in their islands, as "merchants" encouraged young people to

get deeply in their debt, so that when they grew up they could keep them

in their clutches and subject them to a state of semi-slavery, as with

increasing families and low wages it was then impossible to get out of

debt. We were very sorry to see these fine young men leaving the

country, and when we thought of the wild and almost deserted islands we

had just visited, it seemed a pity they could not have been employed

there. We had a longer and much smoother passage than on our outward

voyage, and the fog had given place to a fine, clear atmosphere as we

once more entered the fine harbour of Kirkwall, and we had a good view

of the town, which some enthusiastic passenger described as the

"Metropolis of the Orcadean Archipelago."

Tuesday, September 12th.

We narrowly escaped a bad accident as we were leaving the St.

Magnus. She carried a large number of sheep and Shetland ponies on

deck, and our way off the ship was along a rather narrow passage formed

by the cattle on one side and a pile of merchandise on the other. The

passengers were walking in single file, my brother immediately in front

of myself, when one of the ponies suddenly struck out viciously with its

hind legs just as we were passing. If we had received the full force of

the kick, we should have been incapacitated from walking; but

fortunately its strength was exhausted when it reached us, and it only

just grazed our legs. The passengers behind thought at first we were

seriously injured, and one of them rushed forward and held the animal's

head to prevent further mischief; but the only damage done was to our

overalls, on which the marks of the pony's hoofs remained as a record of

the event. On reaching the landing-place the passengers all came forward

to congratulate us on our lucky escape, and until they separated we were

the heroes of the hour, and rather enjoyed the brief notoriety.

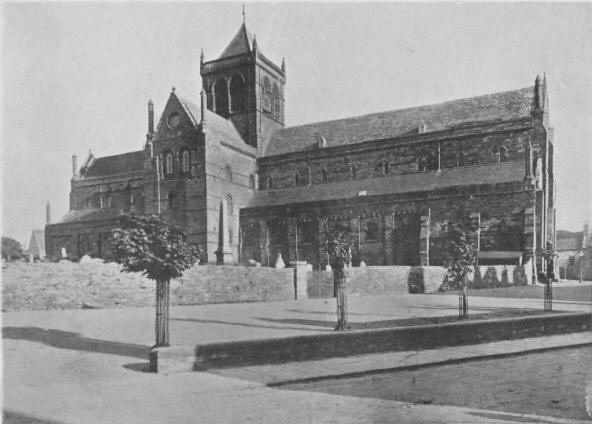

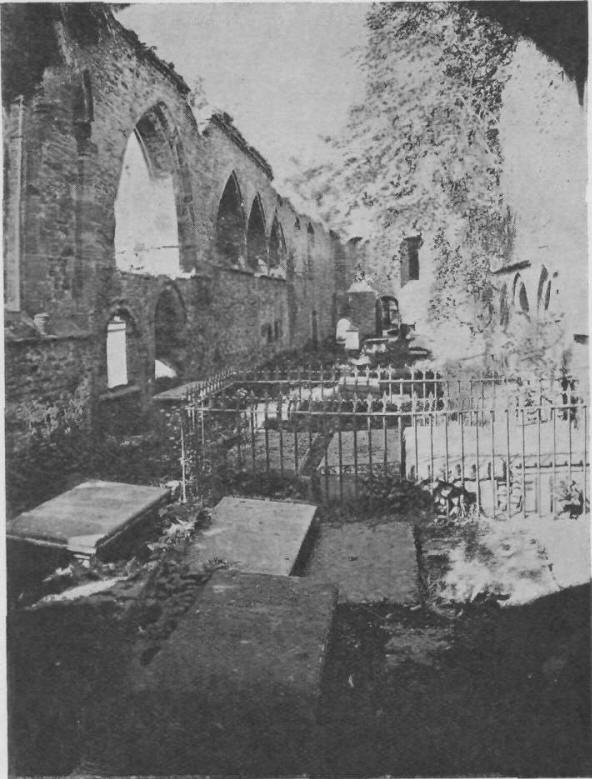

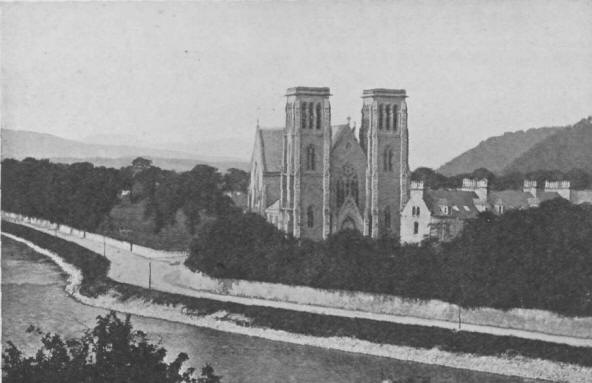

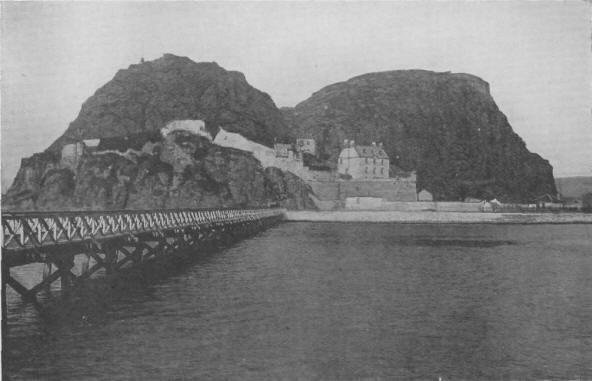

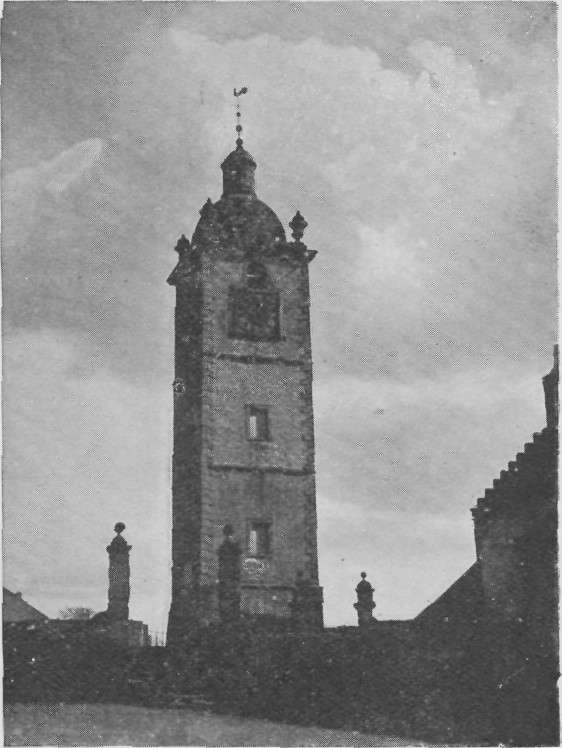

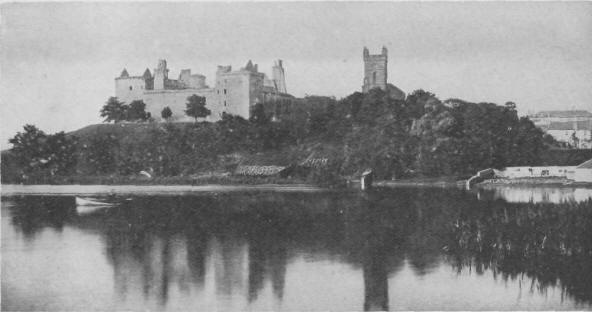

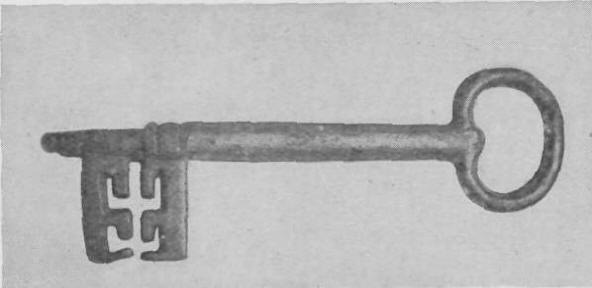

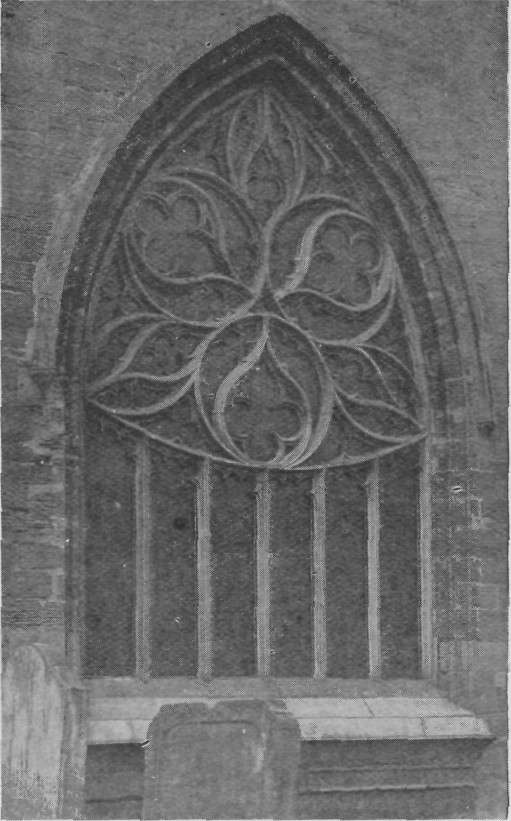

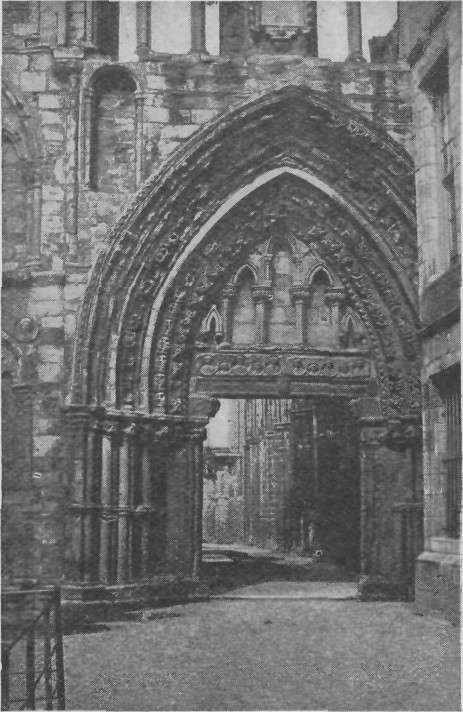

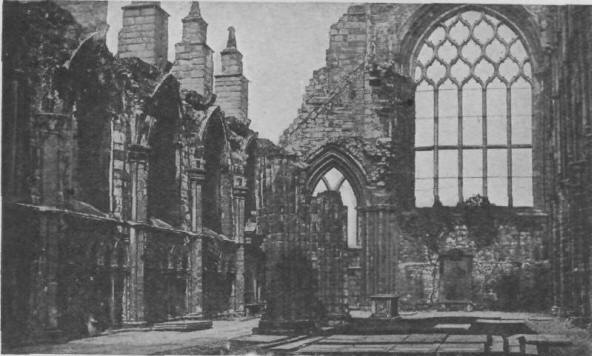

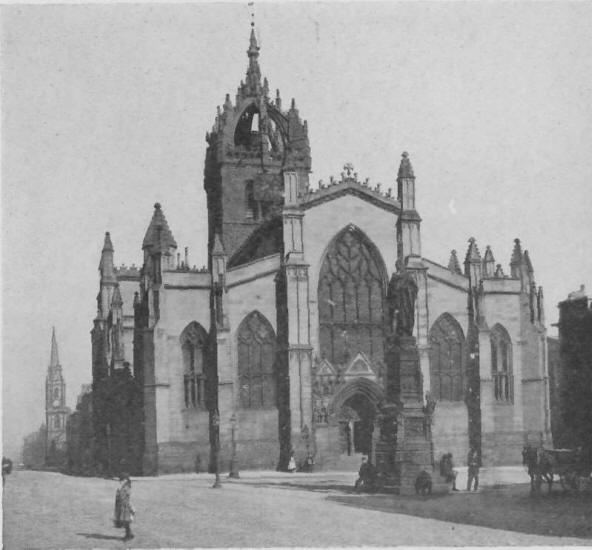

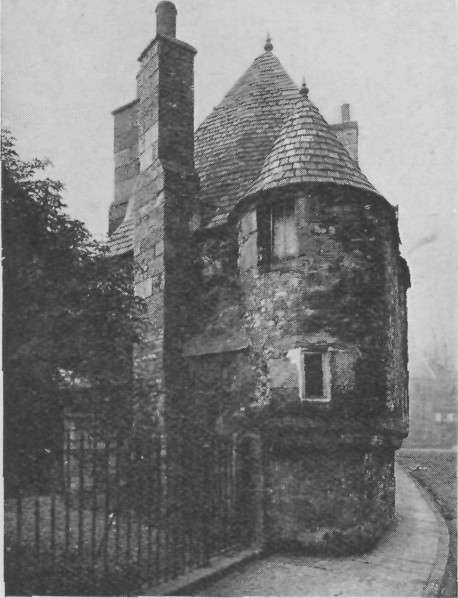

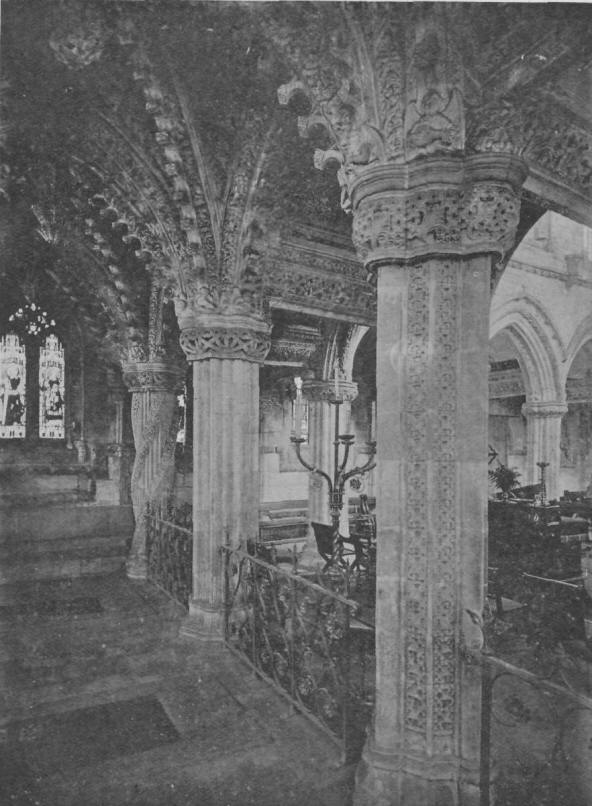

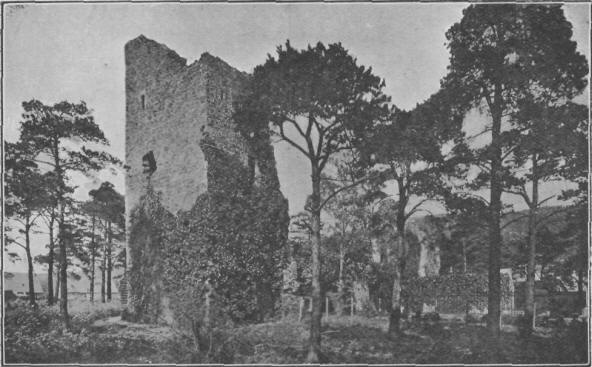

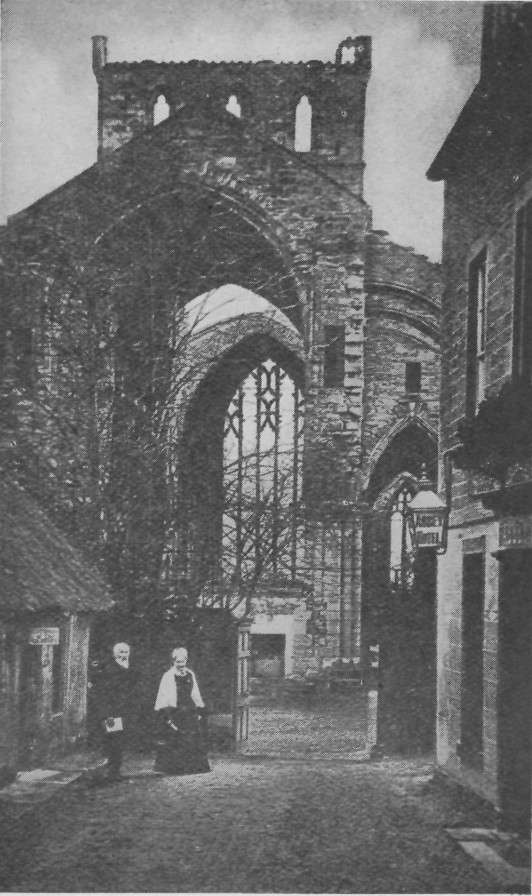

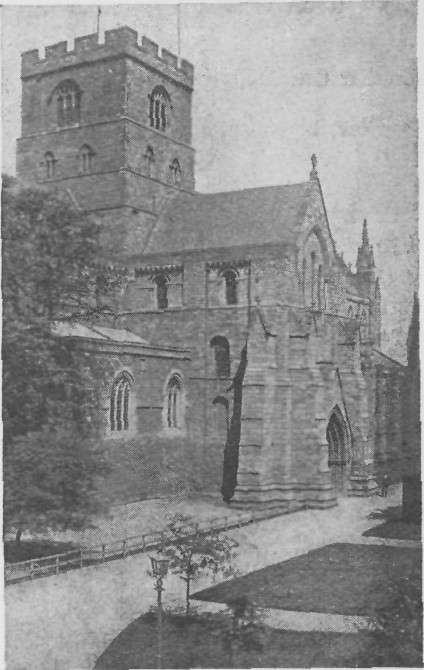

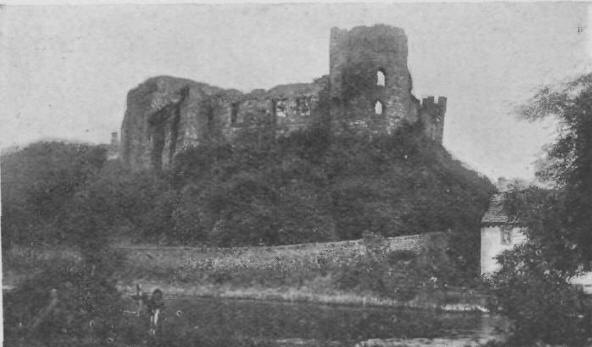

ST. MAGNUS CATHEDRAL KIRKWALL

There was an old-world appearance about Kirkwall

reminiscent of the time

When Norse and Danish galleys plied

Their oars within the Firth

of Clyde,

When floated Haco's banner

trim

Above Norwegian warriors

grim,

Savage of heart and huge of

limb.

for it was at the palace there that Haco, King of Norway,

died in 1263. There was only one considerable street in the town, and

this was winding and narrow and paved with flags in the centre,

something like that in Lerwick, but the houses were much more foreign in

appearance, and many of them had dates on their gables, some of them as

far back as the beginning of the fifteenth century. We went to the same

hotel as on our outward journey, and ordered a regular good "set out" to

be ready by the time we had explored the ancient cathedral, which, like

our ship, was dedicated to St.

Magnus. We were directed to call at a cottage for the key, which was

handed to us by the solitary occupant, and we had to find our way as

best we could. After entering the ancient building, we took the

precaution of locking the door behind us. The interior looked dark and

dismal after the glorious sunshine we had left outside, and was

suggestive more of a dungeon than a place of worship, and of the dark

deeds done in the days of the past. The historian relates that St.

Magnus met his death at the hands of his cousin Haco while in the church

of Eigleshay. He had retired there with a presentiment of some evil

about to happen him, and "while engaged in devotional exercises,

prepared and resigned for whatever might occur, he was slain by one

stroke of a hatchet. Being considered eminently pious, he was looked

upon as a saint, and his nephew Ronald built the cathedral in accordance

with a vow made before leaving Norway to lay claim to the Earldom of

Orkney." The cathedral was considered to be the best-preserved relic of

antiquity in Scotland, and we were much impressed by the dim religious

light which pervaded the interior, and quite bewildered amongst the dark

passages inside the walls. We had been recommended to ascend the

cathedral tower for the sake of the fine view which was to be obtained

from the top, but had some difficulty in finding the way to the steps.

Once we landed at the top of the tower we considered ourselves well

repaid for our exertions, as the view over land and sea was very

beautiful. Immediately below were the remains of the bishop's and earl's

palaces, relics of bygone ages, now gradually crumbling to decay, while

in the distance we could see the greater portion of the sixty-seven

islands which formed the Orkney Group. Only about one-half of these were

inhabited, the remaining and smaller islands being known as holms, or

pasturages for sheep, which, seen in the distance, resembled green

specks in the great blue sea, which everywhere surrounded them.

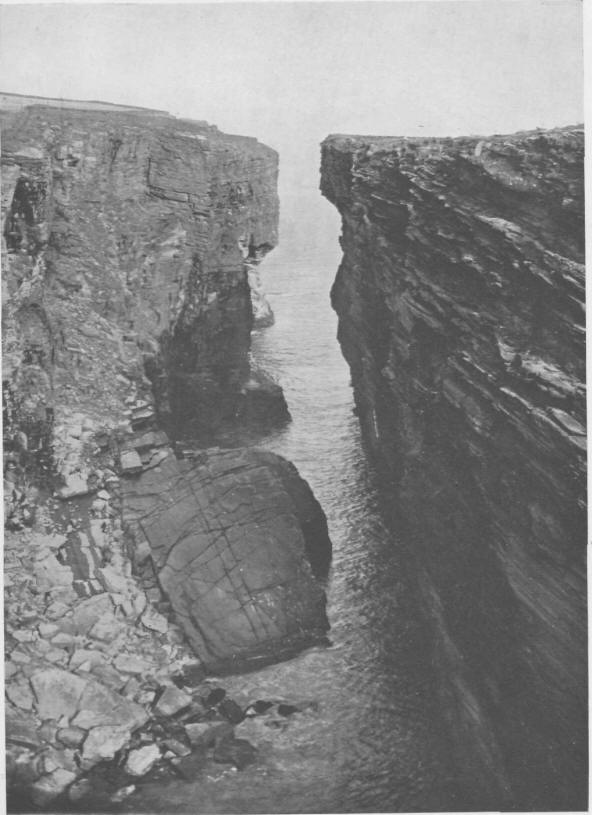

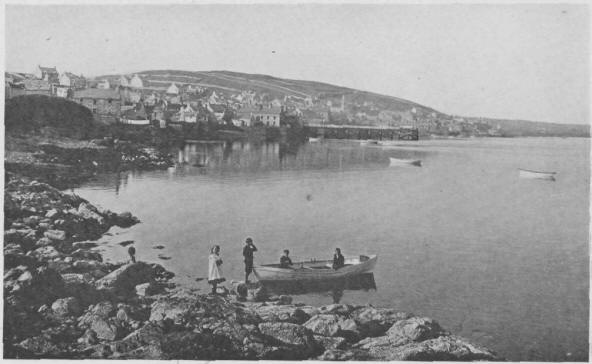

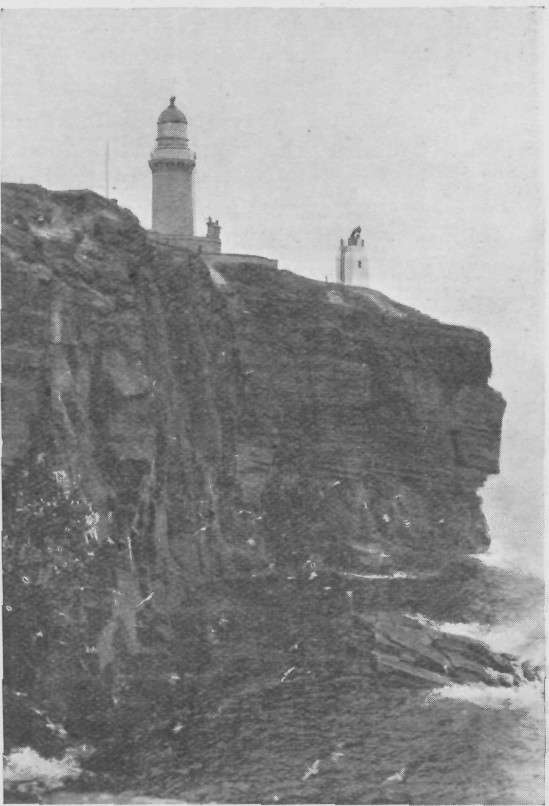

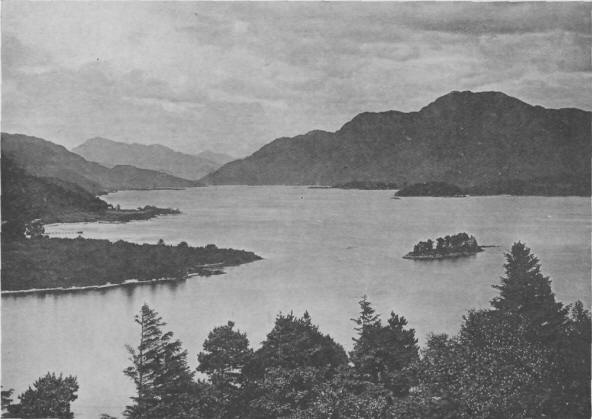

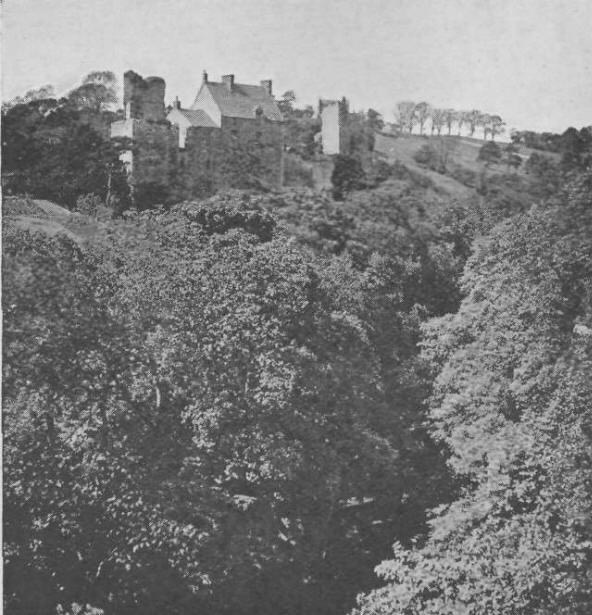

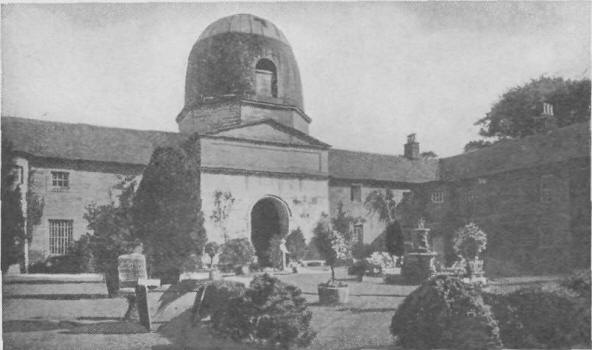

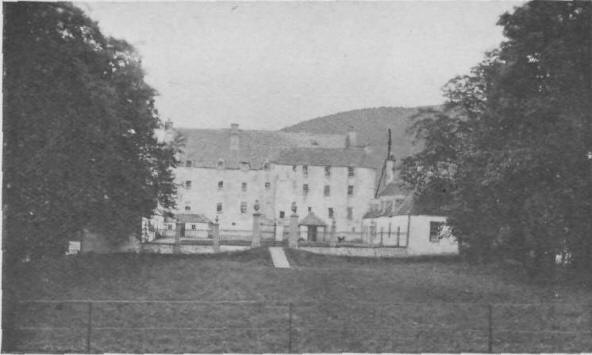

STROMNESS

I should have liked to stay a little longer surveying

this fairy-like scene, but my brother declared he could smell our

breakfast, which by this time must have been waiting for us below. Our

exit was a little delayed, as we took a wrong turn in the rather

bewildering labyrinth of arches and passages in the cathedral walls, and

it was not without a feeling of relief that we reached the door we had

so carefully locked behind us. We returned the key to the caretaker, and

then went to our hotel, where we loaded ourselves with a prodigious

breakfast, and afterwards proceeded to walk across the Mainland of the

Orkneys, an estimated distance of fifteen miles.

On our rather lonely way to Stromness we noticed that

agriculture was more advanced than in the Shetland Islands, and that the

cattle were somewhat larger, but we must say that we had been charmed

with the appearance of the little Shetland ponies, excepting perhaps the

one that had done its best to give us a farewell kick when we were

leaving the St. Magnus.

Oats and barley were the crops chiefly grown, for we did not see any

wheat, and the farmers, with their wives and children, were all busy

harvesting their crops of oats, but there was still room for extension

and improvement, as we passed over miles of uncultivated moorland later.

On our inquiring what objects of interest were to be seen on our way,

our curiosity was raised to its highest pitch when we were told we

should come to an underground house and to a large number of standing

stones a few miles farther on. We fully expected to descend under the

surface of the ground, and to find some cave or cavern below; but when

we got to the place, we found the house practically above ground, with a

small mountain raised above it. It was covered with grass, and had only

been discovered in 1861, about ten years before our visit. Some boys

were playing on the mountain, when one of them found a small hole which

he thought was a rabbit hole, but, pushing his arm down it, he could

feel no bottom. He tried again with a small stick, but with the same

result. The boys then went to a farm and brought a longer stick, but

again failed to reach the bottom of the hole, so they resumed their

play, and when they reached home they told their parents of their

adventure, and the result was that this ancient house was discovered and

an entrance to it found from the level of the land below.

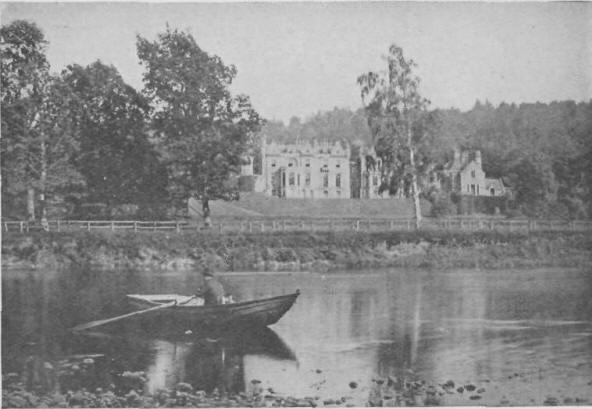

SHETLAND PONIES.

We went in search of the caretaker, and found him busy

with the harvest in a field some distance away, but he returned with us

to the mound. He opened a small door, and we crept behind him along a

low, narrow, and dark passage for a distance of about seventeen yards,

when we entered a chamber about the size of an ordinary cottage

dwelling, but of a vault-like appearance. It was quite dark, but our

guide proceeded to light a number of small candles, placed in rustic

candlesticks, at intervals, round this strange apartment. We could then

see some small cells in the wall, which might once have been used as

burial places for the dead, and on the walls themselves were hundreds of

figures or letters cut in the rock, in very thin lines, as if engraved

with a needle. We could not decipher any of them, as they appeared more

like Egyptian hieroglyphics than letters of our alphabet, and the only

figure we could distinguish was one which had the appearance of a winged

dragon.

The history of the place was unknown, but we were

afterwards told that it was looked upon as one of the most important

antiquarian discoveries ever made in Britain. The name of the place was

Maeshowe. The mound was about one hundred yards in circumference, and it

was supposed that the house, or tumulus, was first cut out of the rock

and the earth thrown over it afterwards from the large trench by which

it was surrounded.

"STANDING STONES OF STENNESS."

Our guide then directed us to the "Standing Stones of

Stenness," which were some distance away; but he could not spare time to

go with us, so we had to travel alone to one of the wildest and most

desolate places imaginable, strongly suggestive of ghosts and the

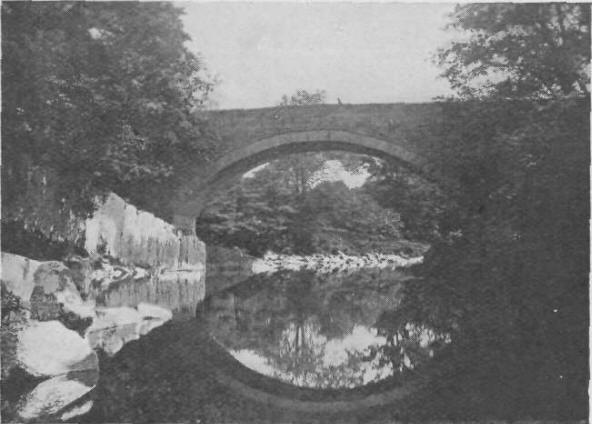

spirits of the departed. We crossed the Bridge of Brogar, or Bruargardr,

and then walked along a narrow strip of land dividing two lochs, both of

which at this point presented a very lonely and dismal appearance.

Although they were so near together, Loch Harry contained fresh water

only and Loch Stenness salt water, as it had a small tidal inlet from

the sea passing under Waith Bridge, which we crossed later. There were

two groups of the standing stones, one to the north and the other to the

south, and each consisted of a double circle of considerable extent. The

stones presented a strange appearance, as while many stood upright, some

were leaning; others had fallen, and some had disappeared altogether.

The storms of many centuries had swept over them, and "they stood like

relics of the past, with lichens waving from their worn surfaces like

grizzly beards, or when in flower mantling them with brilliant orange

hues," while the areas enclosed by them were covered with mosses, the

beautiful stag-head variety being the most prominent. One of the poets

has described them:

The heavy rocks of giant size

That o'er the land in circles

rise.

Of which tradition may not

tell,

Fit circles for the Wizard

spell;

Seen far amidst the scowling

storm

Seem each a tall and phantom

form,

As hurrying vapours o'er them

flee

Frowning in grim security,

While like a dread voice from

the past

Around them moans the

autumnal blast!

These lichened "Standing Stones of Stenness," with the

famous Stone of Odin about 150 yards to the north, are second only to

Stonehenge, one measuring 18 feet in length, 5 feet 4 inches in breadth,

and 18 inches in thickness. The Stone of Odin had a hole in it to which

it was supposed that sacrificial victims were fastened in ancient times,

but in later times lovers met and joined hands through the hole in the

stone, and the pledge of love then given was almost as sacred as a

marriage vow. An antiquarian description of this reads as follows: "When

the parties agreed to marry, they repaired to the Temple of the Moon,

where the woman in the presence of the man fell down on her knees and

prayed to the God Wodin that he would enable her to perform, all the

promises and obligations she had made, and was to make, to the young man

present, after which they both went to the Temple of the Sun, where the

man prayed in like manner before the woman. They then went to the Stone

of Odin, and the man being on one side and the woman on the other, they

took hold of each other's right hand through the hole and there swore to

be constant and faithful to each other." The hole in the stone was about

five feet from the ground, but some ignorant farmer had destroyed the

stone, with others, some years before our visit.

There were many other stones in addition to the circles,

probably the remains of Cromlechs, and there were numerous grass mounds,

or barrows, both conoid and bowl-shaped, but these were of a later date

than the circles. It was hard to realise that this deserted and

boggarty-looking place was once the Holy Ground of the ancient

Orcadeans, and we were glad to get away from it. We recrossed the Bridge

of Brogar and proceeded rapidly towards Stromness, obtaining a fine

prospective view of that town, with the huge mountain masses of the

Island of Hoy as a background, on our way. These rise to a great height,

and terminate abruptly near where that strange isolated rock called the

"Old Man of Hoy" rises straight from the sea as if to guard the islands

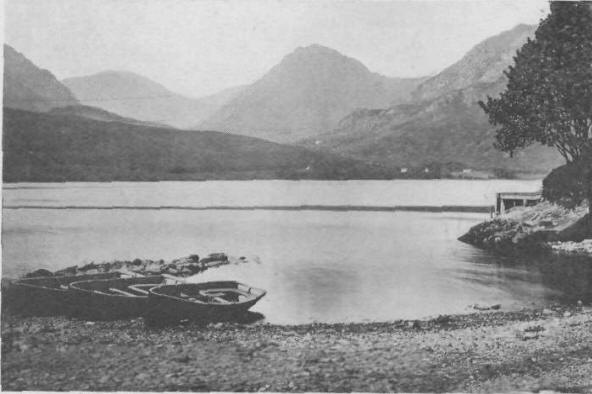

in the rear. The shades of evening were falling fast as we entered

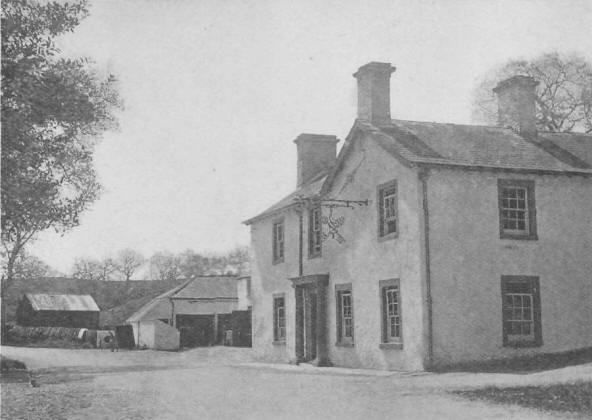

Stromness, but what a strange-looking town it seemed to us! It was built

at the foot of the hill in the usual irregular manner and in one

continuous crooked street, with many of the houses with their

crow-stepped gables built as it were over the sea itself, and here in

one of these, owing to a high recommendation received inland, we stayed

the night. It was perched above the water's edge, and, had we been so

minded, we might have caught the fish named sillocks for our own

breakfast without leaving the house: many of the houses, indeed, had

small piers or landing-stages attached to them, projecting towards the

bay.

We found Mrs. Spence an ideal hostess and were very

comfortable, the only drawback to our happiness being the information

that the small steamboat that carried mails and passengers across to

Thurso had gone round for repairs "and would not be back for a week, but

a sloop would take her place" the day after to-morrow. But just fancy

crossing the stormy waters of the Pentland Firth in a sloop! We didn't

quite know what a sloop was, except that it was a sailing-boat with only

one mast; but the very idea gave us the nightmare, and we looked upon

ourselves as lost already. The mail boat, we had already been told, had

been made enormously strong to enable her to withstand the strain of the

stormy seas, besides having the additional advantage of being propelled

by steam, and it was rather unfortunate that we should have arrived just

at the time she was away. We asked the reason why, and were informed

that during the summer months seaweeds had grown on the bottom of her

hull four or five feet long, which with the barnacles so impeded her

progress that it was necessary to have them scraped off, and that even

the great warships had to undergo the same process.

Seaweeds of the largest size and most beautiful colours

flourish, in the Orcadean seas, and out of 610 species of the flora in

the islands we learned that 133 were seaweeds. Stevenson the great

engineer wrote that the large Algæ, and especially that one he named the

"Fucus esculentus," grew on the rocks from self-grown seed, six feet in

six months, so we could quite understand how the speed of a ship would

be affected when carrying this enormous growth on the lower parts of her

hull.

Wednesday, September 13th.

We had the whole of the day at our disposal to explore

Stromness and the neighbourhood, and we made the most of it by rambling

about the town and then along the coast to the north, but we were seldom

out of sight of the great mountains of Hoy.

Sir Walter Scott often visited this part of the Orkneys,

and some of the characters he introduced in his novels were found here.

In 1814 he made the acquaintance of a very old woman near Stromness,

named Bessie Miller, whom he described as being nearly one hundred years

old, withered and dried up like a mummy, with light blue eyes that

gleamed with a lustre like that of insanity. She eked out her existence

by selling favourable winds to mariners, for which her fee was sixpence,

and hardly a mariner sailed out to sea from Stromness without visiting

and paying his offering to Old Bessie Miller. Sir Walter drew the

strange, weird character of "Norna of the Fitful Head" in his novel The

Pirate from her.

The prototype of "Captain Cleveland" in the same novel

was John Gow, the son of a Stromness merchant. This man went to sea, and

by some means or other became possessed of a ship named the Revenge,

which carried twenty-four guns. He had all the appearance of a brave

young officer, and on the occasions when he came home to see his father

he gave dancing-parties to his friends. Before his true character was

known—for he was afterwards proved to be a pirate—he engaged the

affections of a young lady of fortune, and when he was captured and

convicted she hastened to London to see him before he was executed; but,

arriving there too late, she begged for permission to see his corpse,

and, taking hold of one hand, she vowed to remain true to him, for fear,

it was said, of being haunted by his ghost if she bestowed her hand upon

another.

It is impossible to visit Stromness without hearing

something of that famous geologist Hugh Miller, who was born at Cromarty

in the north of Scotland in the year 1802, and began life as a quarry

worker, and wrote several learned books on geology. In one of these,

entitledFootprints of the Creator in the Asterolepis of Stromness,

he demolished the Darwinian theory that would make a man out to be only

a highly developed monkey, and the monkey a highly developed mollusc. My

brother had a very poor opinion of geologists, but his only reason for

this seemed to have been formed from the opinion of some workmen in one

of our brickfields. A gentleman who took an interest in geology used to

visit them at intervals for about half a year, and persuaded the men

when excavating the clay to put the stones they found on one side so

that he could inspect them, and after paying many visits he left without

either thanking them or giving them the price of a drink! But my brother

was pleased with Hugh Miller's book, for he had always contended that

Darwin was mistaken, and that instead of man having descended from the

monkey, it was the monkey that had descended from the man. I persuaded

him to visit the museum, where we saw quite a number of petrified

fossils. As there was no one about to give us any information, we failed

to find Hugh Miller's famous asterolepis, which we heard afterwards had

the appearance of a petrified nail, and had formed part of a huge fish

whose species were known to have measured from eight to twenty-three

feet in length. It was only about six inches long, and was described as

one of the oldest, if not the oldest, vertebrate fossils hitherto

discovered. Stromness ought to be the Mecca, the happy hunting-ground,

or the Paradise to geologists, for Hugh Miller has said it could furnish

more fossil fish than any other geological system in England, Scotland,

and Wales, and could supply ichthyolites by the ton, or a ship load of

fossilised fish sufficient to supply the museums of the world. How came

this vast number of fish to be congregated here? and what was the force

that overwhelmed them? It was quite evident from the distorted portions

of their skeletons, as seen in the quarried flags, that they had

suffered a violent death. But as we were unable to study geology, and

could neither pronounce nor understand the names applied to the fossils,

we gave it up in despair, as a deep where all our thoughts were drowned.

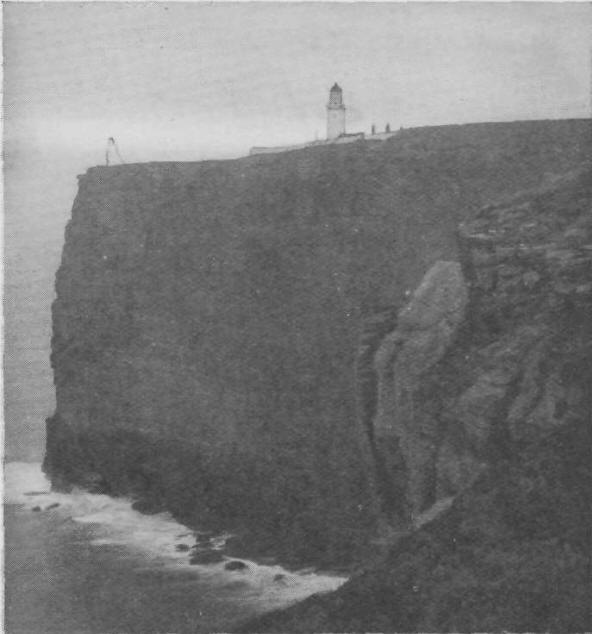

We then walked along the coast, until we came to the

highest point of the cliffs opposite some dangerous rocks called the

Black Craigs, about which a sorrowful story was told. It happened on

Wednesday, March 5th, 1834, during a terrific storm, when the Star

of Dundee, a schooner of about eighty tons, was seen to be drifting

helplessly towards these rocks. The natives knew there was no chance of

escape for the boat, and ran with ropes to the top of the precipice near

the rocks in the hope of being of some assistance; but such was the fury

of the waves that the boat was broken into pieces before their eyes, and

they were utterly helpless to save even one of their shipwrecked

fellow-creatures. The storm continued for some time, and during the

remainder of the week nothing of any consequence was found, nor was any

of the crew heard of again, either dead or alive, till on the Sunday

morning a man was suddenly observed on the top of the precipice waving

his hands, and the people who saw him first were so astonished that they

thought it was a spectre. It was afterwards discovered that it was one

of the crew of the ill-fated ship who had been miraculously saved. He

had been washed into a cave from a large piece of the wreck, which had

partially blocked its entrance and so checked the violence of the waves

inside, and there were also washed in from the ship some red herrings, a

tin can which had been used for oil, and two pillows. The herrings

served him for food and the tin can to collect drops of fresh water as

they trickled down the rocks from above, while one of the pillows served

for his bed and he used the other for warmth by pulling out the feathers

and placing them into his boots. Occasionally when the waves filled the

mouth of the cave he was afraid of being suffocated. Luckily for him at

last the storm subsided sufficiently to admit of his swimming out of the