|

Edited by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Greater Atlanta, GA, USA

Email: jurascot@earthlink.net

Craig Lamont is from Glasgow. He earned his

MA and Master of Research degrees at the University of Strathclyde,

moving to the University of Glasgow to work with Prof. Murray Pittock on

his PhD, completed in November 2015. His PhD thesis, titled “Georgian

Glasgow: the city remembered through literature, objects, and cultural

memory theory,” was part of an AHRC-funded collaborative project between

the University and Glasgow Life, which included a major exhibition How

Glasgow Flourished: 1714-1837 at the Kelvingrove Gallery and Museum. In

the fall of 2016, Craig will be teaching in the department of Scottish

Literature at the University of Glasgow.

This is a different type article for Robert Burns Lives!, one like I’ve

never seen before and one which will open up new work by Lamont and

others and hopefully some of our own readers. You will see how they go

about their research by comparing one, two or three copies of previous

original works. I have found the efforts in this brief article to be of

great interest and will add another dimension to the study of Burns for

us all. It is a treat to welcome Craig Lamont to the pages of Robert

Burns Lives! and I look forward to his return in the future.

My thanks to Patrick Scott for the introduction paragraph above on Craig

and for providing me with his article below. (FRS: 9.14.16)

Burns in the heat of the South:

rare books and modern technology

By Craig Lamont

Recently, I was able to make a two-week

visit to the G. Ross Roy Collection of Robert Burns, at the University

of South Carolina. For the past eight months, I have been working on a

new bibliography of the early Burns editions, to update and expand

Egerer’s long-standard work published in 1964. This project is some of

the preliminary research already underway for the later volumes in the

new AHRC-funded Burns edition, headed by Gerard Carruthers. The new

bibliography, which I have written about for the next Burns Chronicle,

is currently focused on the early editions (1706-1802), but it goes

beyond Egerer’s level of description, for instance by providing full

contents lists, showing not just the first time a Burns poem was

published in book form but each time it was included after that.

So far, the research had kept me mostly in

Glasgow, consulting editions in the Mitchell Library and the

University’s own special collections, and then taking trips also to

Alloway to the Birthplace Museum, and, more frequently, to Edinburgh to

the National Library of Scotland. As I learned from studying Elizabeth

Sudduth’s published catalogue, however, the Roy Collection has both a

large number of the early editions and some rarities that are not

available (or extant) in Scotland.

The main library entrance, University of

South Carolina\

I arrived in the middle of July. The

temperature reached 98.6°F (37°C) on the first day, and stayed around

100° for the rest of my stay, with occasional relief from late afternoon

thunderstorms. Suddenly, writing “Burns” under “research topic” on the

library sign-in sheet felt more appropriate than ever. The library

itself is kept cool, and there was a shelf-full of editions ready for me

to begin work. It reminded me of the Glasgow library between semesters:

that eerie silence interrupted by the creak of a centuries-old page,

printed on with centuries-old ink. You might imagine that there is

little left to say about the story of these books, but these early books

invite a different sense of awe from a manuscript, and tell a much

different (sometimes much larger) story. The visit to South Carolina

also allowed me to work directly with Patrick Scott (who is one of the

project advisers) as questions came up, rather than by email as in

previous months. Columbia and the University were more than welcoming.

I’ve felt right at home, despite the consistent appearance of that

unusual simmering object in the sky.

The Roy-Scott Room in Hollings Library,

University of South Carolina

(photo: Robert P. Smith)

The primary purpose of my visit was to

develop and type up bibliographical descriptions for the rare editions

in the Roy Collection. One special item that I had never previously seen

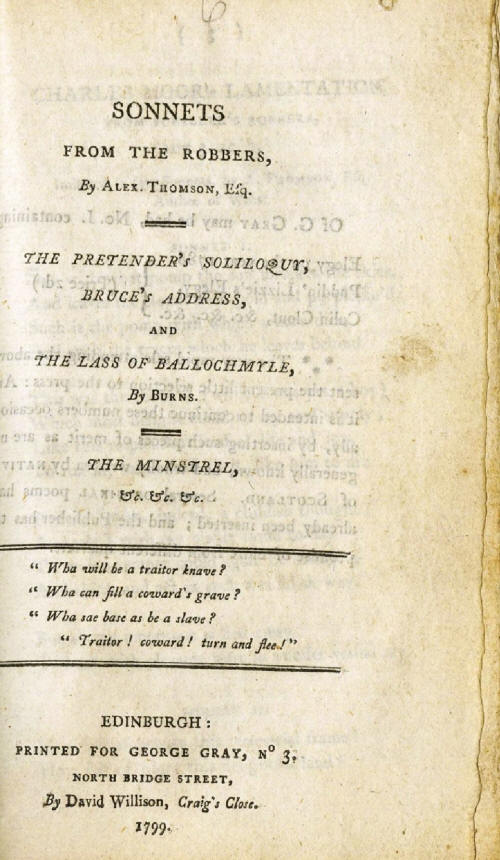

was the second of the “Gray tracts.” In 1799, George Gray, an Edinburgh

bookseller, published two small chapbooks. Egerer hadn’t seen either of

them, but included a description of one, Elegy on the Year Eighty-Eight

(Egerer 37), based on a photo copy sent him by Davidson Cook (Egerer 37,

pp. 58-59). The other one, Sonnets from the Robbers, which includes

“Bruce’s Address” (“Scots wha hae”), doesn’t even have an Egerer number,

though Egerer footnotes a newspaper report that it had once existed.

When Professor Roy found it, there was no other recorded copy, and there

are still only two others reported worldwide.

Sonnets from the Robbers ... Bruce’s Address

(Edinburgh: John Gray 1799)

Image courtesy of the G. Ross Roy Collection, University of South

Carolina Libraries

I also wanted a chance to examine additional

copies of editions I had seen in Scotland, especially where the library

copies I had used first had been rebound or seemed irregular in some

way. In Glasgow, I hadn’t been able to make a side-by-side comparison of

the 1787 copies of Burns Poems with the Belfast and Dublin imprints on

the title page, seeing a Dublin copy in the Mitchell and going across to

Edinburgh to see a Belfast, but the Roy Collection has both. Towards the

end of my first week, for instance, Patrick Scott and I sat down in the

reading room with seven copies of the 1787 Edinburgh edition (Egerer 2;

Roy). Most Burnsians know about the two type-settings for the major

portion of the edition, known from the most famous misprint as the “Skinking:”

and “Stinking” settings, but there are hundreds of other minor variants

between the two (Murdoch), and we were able to assess what kind of

research will be needed in future. Alongside work for the bibliography,

we were able to ask new questions about the story behind these variants.

How much of a role did Burns himself play while the Edinburgh edtion was

being printed and reset? What was the exact relationship between the two

Irish title-pages? My visit seeded questions for future work and let us

begin collaboration on two articles that will look at these questions in

a way that bibliography itself won’t allow (one down, one still to go:

see Scott and Lamont, forthcoming).

There is certainly more than one library where these questions could be

investigated, but the visit to the University of South Carolina let me

get experience with some technology that might help. This kind of

research involves “collation,” or close comparison, in this case of

details from multiple copies of the same edition. In Burns’s time,

printers sometimes made small changes to a page while they were

printing, so that some copies show the first variant and some the

second. (Confusingly, the word “collation” is also used in at least two

other senses, by textual editors for comparison between different

editions and manuscripts, and by bibliographers to describe the way the

sheets of a printed book are folded and assembled to form the finished

volume.) The kind of collation we needed to do for the Burns project is

tedious, and if it is done by simply looking backwards and forwards

between two copies of a book (the so-called “Wimbledon” or “ping-pong”

method), small differences often get overlooked. Over the years,

scholars have developed several optical and digital ways to tackle the

problem.

For the Burns editions, I tried out three different optical “collating

machines” (Smith 2002). These all use a system of mirrors so that the

image from one copy of a book is seen as superimposed over the image of

the same page in another copy, and you can notice even small changes

such as a new comma, apostrophe, or spelling correction. I tried first

with a Lindstand Comparator, a large, desktop, contraption with a

stereoscopic eyepiece like a pair of binoculars, developed by a

professor at South Carolina in the late 1960s, but it is bulky and I

found it tricky to use.

I had better luck with a more recent

invention, Carter Hailey’s Comet. Professor David Lee Miller, a

distinguished colleague of Patrick Scott’s, has a Comet for his research

on Elizabethan editions of Spenser, and he kindly set it up in the

library’s Roy-Scott Room for me to try. The Comet is portable (folded

up, it fits into a small briefcase), and it allows you to compare a

printed book in one library with the digital image on a laptop of a

different copy elsewhere. I tried it out for sample pages from a copy of

the Edinburgh edition and the digitized version (ECCO) available in the

Glasgow library. Like the Lindstrand, the Comet works like a

stereoscope, meaning you need two good eyes, but it doesn’t have an

eyepiece. The mirrors are like anglepoise lamps, so that it takes a

great deal of practice to get them aligned just right, till you can lean

in and get the two pages, one seen with each eye, to merge. However, the

effect is quite impressive when you trick your brain into letting it

happen.

Prof. David Miller demonstrating the Comet,

in the Roy-Scott Room

(photo: John Sawvell)

The third collator I used, the Hinman, is

the oldest but still the gold standard for optical collation. It was

invented in 1946 by Charlton Hinman, who had spent the war in naval

intelligence. The long-running story was that he got his idea from the

way aerial photos were compared before and after bombing raids. The more

recent account is that he adapted the key element from a device that let

astronomers compare successive time-lapse photos of distant galaxies

(Smith, 2000). Hinman himself famously used his invention to collate

fifty-five copies of the Shakespeare first folio, discovering hidden

variants on one page out of every six. Between 1946 and 1979, Hinman and

his collaborator, a retired engineer, manufactured and sold just over

fifty machines, mostly to libraries, but some to pharmaceutical

companies, and probably one to the CIA (don’t ask). The Hinman machine

now at South Carolina (they used to own two) was purchased in 1973.

Craig Lamont comparing two Edinburgh

editions on the Hinman Collator

(photo: John Sawvell)

The Hinman is huge (about six foot high and

five feet across), it’s certainly not portable, and it requires a nearby

electrical outlet. Instead of relying on stereoscopic vision, it

alternates images from the two pages so the differences stand out. Its

accuracy also comes from using permanently aligned mirrors and

eyepieces, and from lighting up the pages being compared. You place the

two copies in the two book-cradles, with the pages held flat by glass

covers, switch on, and line the images up by moving the right-hand

cradle. Then, when you nudge against a lever in the knee-hole, the bulbs

flash intermittently, images of the two pages alternate second by

second, and you see the differences. I found it to be the most effective

of the three collators. It was particularly good in doing comparison of

the two 1787 Irish title-pages, and to my surprise it also worked to

identify variants between the two different settings of the Edinburgh

edition.

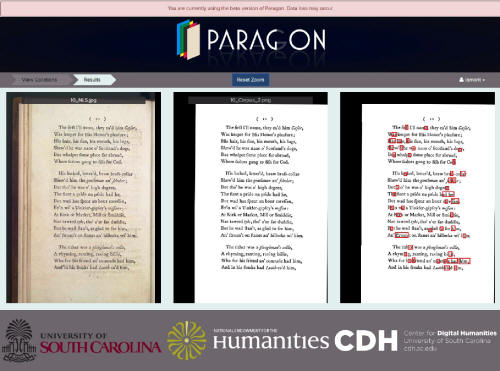

What we hadn’t anticipated was the chance to try out a fourth method, a

new digital alternative to the optical machines. Professor Miller is not

only an English professor but also Director of the University’s Center

for Digital Humanities, and he arranged a demo for us of a new software

model, Paragon, that they have been developing for work on the Spenser

project (Miller and Wang). Paragon is an intelligent digital collator

that does much of the work for you, once you have obtained good digital

scans of the texts you want to compare. While there are different kinds

of comparison (pages from two copies, pages from multiple copies against

a single master copy, and so on), for each comparison Paragon produces a

screen of at least three images: one for each original page, and a third

Paragon-made image with red boxes around the differences it has

detected.

Using PARAGON to collate two copies of the

Kilmarnock Burns

Image courtesy of Center for Digital Humanities, University of South

Carolina

After the initial demo, I tried it out with

sample pages from the Kilmarnock copies that had been digitized by

Glasgow and the NLS. Paragon doesn’t interpret what it finds, so if

there is a small ink-smudge, or if one letter has got damaged, on one of

the copies, it picks that “variant” up as “difference.” The differences

highlighted in the right hand image shown here are just that, not the

kind of variants that show Burns making corrections during printing. But

if it picks up differences as small as these, you can bet it will pick

up any actual printing variants—wording or spelling (including

vernacular vs formal spelling), punctuation, misprints that got

corrected midway through printing. It gives you the chance to analyse

the results of something, without having to rely on your ability to see

every difference for yourself. Paragon is a new beginning in collation,

potentially enabling new research into how the Kilmarnock was printed.

With all these new experiences and ideas, I headed back to Scotland. The

original bibliographical project is now almost complete, but the work

has highlighted the potential for a lot more detailed investigation into

the early printing history of individual editions. The last attempt at a

full comparison of variants between the two settings of the 1787

Edinburgh edition appears to have been in 1895, and there seems never to

have been a systematic collation of multiple copies of the 1786

Kilmarnock edition. Getting to use the Comet, the Hinman, and the

preliminary version of Paragon, gives me new ideas about how such

investigation could be done. And if Ross Roy could find a

previously-unrecorded copy of a chapbook that had eluded Egerer, perhaps

another unrecorded Burns pamphlet still lurks awaiting a lucky visitor

on the dusty shelves of some unsuspecting (and one hopes airconditioned)

library.

References

Murdoch, J. Barclay, “The Second Edition of Burns,” Burns Chronicle, 1st

series, 4 (1895), 107-120:

http://www.rbwf.org.uk/digitised-chronicles/

Egerer, J. W., A Bibliography of Robert Burns (Edinburgh: Oliver and

Boyd, 1964; Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1965).

Lamont, Craig, “The beginning of a new bibliography of Robert Burns

editions,” Burns Chronicle for 2017 (forthcoming).

Miller, David Lee, and Song Wang, “Paragon,” Center for Digital

Humanities, University of South Carolina:

https://sc.edu/about/centers/digital_humanities/projects/paragon.phpARAGON

Roy, G. Ross, “How Many Copies Were Printed of Burns’s Second

(Edinburgh) Edition?,” Robert Burns Lives!, 150 (August 29, 2012), at:

http://www.electricscotland.com/familytree/frank/burns_lives150.htm

Sudduth, Elizabeth, The G. Ross Roy Collection of Robert Burns, An

Illustrated Catalogue (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press,

2009).

Smith, Steven Escar, “’The Eternal Verities Verified’: Charlton Hinman

and the Roots of Mechanical Collation,” Studies in Bibliography, 53

(2000), 129-162.

________________, “’Armadillos of Invention’: A Census of Mechanical

Collators,” Studies in Bibliography, 55 (2002), 133-170.

Scott, Patrick, and Craig Lamont, “The First Irish Edition of Robert

Burns: A Reexamination,” Scottish Literary Review (forthcoming). |