This could not but add

greatly to the prosperity and commercial importance of Leith. Yet James

II. does not seem to have had such close association with the Port as his

father had through his foundation and building of the Kingís Wark, his

fondness for pleasure-cruising on the waters of the Firth, and his

interest in shipbuilding and commerce which he did so much to encourage.

Perhaps we might have heard more of the interest of James II. in Leith,

and his connection with it, had the chronicles of his reign not been so

meagre and scanty. Legend, however, sometimes comes to our aid, and we

have a very picturesque one describing Jamesís first recorded visit to

Leith, although he must often have been in the town with his parents and

sisters on their way across the Firth to Perth.

Sir William Crichton, the

Governor of Edinburgh Castle, who, you remember, was one of the

benefactors of St. Anthonyís Hospital, had the queen-mother and the

little king so completely in his power in Edinburgh Castle that they were

virtually prisoners. But Crichton was cleverly outwitted by the queen, who

pretended she was going on a pilgrimage to pray for her sonís health,

and earnestly commended him to his tender care during her absence.

Starting early in the morning she placed her luggage in one chest and the

little king in another, and slung them both from the back of a sumpter

horse. Instead of riding to the shrine of Our Lady at Whitekirk, however,

she galloped to the Kingís Wark on the Shore, and embarking, perhaps in

the kingís barge, perhaps in her own "new little ship," and

sailing under a fair breeze, she was well on her way to Stirling Castle

before Crichton discovered how the queen had proved too clever for him.

In spite of the strife and

disorder that prevailed even in our own neighbourhood between Crichton and

the Forresters of Corstorphine, the trade and commerce of Leith steadily

increased. In 1438, the very first year of Jamesís reign, we get a

glimpse of her growing wool trade with Flanders in the regulations

enjoining all traders sailing outward from the port to give a sack freight

in support of the Scots chaplain at St. Ninianís Chapel in the Carmelite

church at Bruges. Although we have scant record of any association of

James Mm-self with our town, yet he did much to encourage its commerce.

Like his father, King James

granted a charter to the merchant burgesses of Edinburgh, empowering them

to levy certain tolls and dues on the shipping for the upkeep of the

harbour, whose state of disrepair had been the cause of much loss of life.

The Leithers, being "unfree," were again treated as strangers in

their own town, and had to pay the double dues of foreigners. This, of

course, was in strict accordance with the laws and customs of the time,

and, while the Leithers might try to evade the higher charges, they did

not regard them as unjust, for they were equally ready when occasion arose

to prevent strangers from sharing any of the few privileges they

themselves possessed.

There was constant coming

and going of embassies for the promotion of trade between Leith and

Flanders throughout the whole of James II.ís reign. To add Iustre to one

of these, the king sent with it his own sister Mary, when he, no doubt,

came down from Holyrood to the Shore with a company of nobles to see her

off. In her honour splendid receptions were held at Bruges, and the trade

between Leith and that noted seat of commerce was placed on a more

flourishing basis. Another frequent voyager between Leith and Flanders on

business of state, mostly connected with trade, was Alexander Napier, upon

whom for his many services James bestowed the lands of Merchiston, which,

with the old castle of the same name, the family still possess.

Two events of this time

were to place the peoples of Scotland and the Netherlands on a very

friendly footing all through Jamesís reign. The first of these was the

marriage of the kingís sister Mary in 1444 with the Lord of Veere, in

Holland. There is a tradition that the Princess Mary, as we would expect,

encouraged Scots traders to come to Veere. However this may be, Veere some

time after became the chief centre of Leithís commercial intercourse

with the Continent, and continued to hold this position right down to the

period of tile Napoleonic wars.

The second and more

important of the two events that drew into closer alliance the people of

Scotland with those of the Netherlands was the marriage of James II.

himself to Mary, the only daughter and heiress of the wealthy Duke of

Gueldres. Leith was the natural port of arrival for distinguished

foreigners on their way to the Court at Holyrood, and it was to Leith that

this beautiful and accomplished princess came in 1449, the first of

several foreign princesses who landed at the Shore of Leith to become

Scottish queens. Her departure from Holland had been delayed by fear of

attacks from English warships, which were ever ready, even in times of

peace, to waylay ships sailing to and from Scotland. The fleet arrived

safely at Leith, however, where the princess and her brilliant train were

met by the Provost of Edinburgh and a great concourse of citizens as she

stepped ashore at the Kingís Wark.

We can picture to ourselves

the gay and splendid scene on the Shore on that sunny day in June, when

Sir William Crichton, who had been sent to accompany her to Scotland,

introduced the princess to the provost and the gay company of lords and

ladies who had ridden down from Holyrood to meet her. It is difficult for

us in our day, when dress is so simple in form and sober in colour, to

realize the pomp and splendour of a royal progress in medieval times, when

costume was so gay, and so extravagant in fashion, and its costly

materials showed, as they no longer do in our time, the rank and wealth of

their wearers. The arrival of the kingís chosen bride aroused the

greatest interest and enthusiasm. The people crowded the narrow

thoroughfares, that did duty for streets in the Leith of those days, and

the galleries and outside stairs of the quaint, timber-fronted houses,

which were gaily decorated with flowers and tapestry.

The

princess had a joyous welcome as she rode on horseback, pillionwise,

behind the Lord of Veere in accordance with the custom of the time, for

side-saddles for ladies were unknown in Scotland until Mary Queen of Scots

brought them with her from France. It was with difficulty that the

cavalcade made its way by the Rotten Row and the Kirkgate to St. Anthonyís

Hospital, where Alexander Napier, the kingís treasurer, had arranged for

refreshment before the princess set out for the city. In the Guest-house

of the Blackfriarsí Monastery, whose vaulted gateway stood at the

Cowgate end of the Blackfriarsí Wynd, the princess was warmly welcomed

by the youthful king.

The

princess had a joyous welcome as she rode on horseback, pillionwise,

behind the Lord of Veere in accordance with the custom of the time, for

side-saddles for ladies were unknown in Scotland until Mary Queen of Scots

brought them with her from France. It was with difficulty that the

cavalcade made its way by the Rotten Row and the Kirkgate to St. Anthonyís

Hospital, where Alexander Napier, the kingís treasurer, had arranged for

refreshment before the princess set out for the city. In the Guest-house

of the Blackfriarsí Monastery, whose vaulted gateway stood at the

Cowgate end of the Blackfriarsí Wynd, the princess was warmly welcomed

by the youthful king.

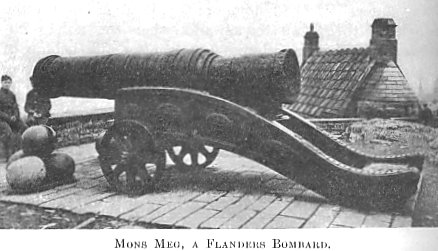

James, like his father, was

keenly interested in artillery, and during his reign "bombards,"

as the great guns of those times were called, were frequent articles of

cargo between Flanders and Leith, where they were stored in the Kingís

Wark or taken to Edinburgh Castle. Among these was the great cannon from

Mons, which, as Mons Meg, is still an object of so much interest and

curiosity to all visitors to the Castle. We can easily imagine the excited

interest Megís arrival on the Shore would arouse among all the people of

the surrounding district, and we may feel certain that, in her progress

towards Edinburgh, she would be accompanied by as large and curious crowds

as Leith showed on the arrival of the first "tank."

His interest in gunnery was

to cost James his life, for he was killed at the siege of Roxburgh Castle

in 1460 by the bursting of one of those bombards in which he used to take

such pride. We may look on Trinity College Church and the Kingís Pillar

in St. Gilesí as tributes of his sorrowing queen to the memory of her

ill-fated husband, whose untimely death plunged Scotland once more into

all the disorder and lawlessness that were wont to prevail when the king

was a child, and which did so much injury to trade and commerce.

During the minority of

James III. the country was undisturbed by foreign invasion, for England

was distracted by the Wars of the Roses, and Scotland was thus left in

peace. That is why trade and commerce still made some progress in spite of

Jamesís weak rule, for he was neither a soldier nor a statesman. As he

grew to manís estate strife and lawlessness continued, for he developed

all the Stuartsí love for favourites, and thus set the nobles against

him. One of his early favourites was Thomas Boyd, a man of great charm of

manner, whom the king had created Earl of Arran, and had married to his

sister Mary. It was this Arran who sailed from Leith on an embassy to the

Court of Denmark to arrange a treaty of marriage between King James and

the saintly Princess Margaret of that country.

His

embassy was successful in its mission. By the terms of the marriage

treaty, which is still preserved in the Register House, the Orkney and

Shetland Islands came to Scotland as Margaretís dowry, for her father

had no money to spare her. Arran conducted the princess from Denmark to

Leith in July 1469, where her landing rivalled in pomp and splendour that

of Mary of Gueldres some twenty years before. But in the pageantry of this

gala day the brilliant Arran had no share. During his absence his many

enemies had poisoned the mind of the king against him, and his life was

forfeit. Anxiously and in secret, somewhere near the Shore, his devoted

wife, the Princess Mary, awaited his arrival with the Danish fleet in

Leith Roads, and, stealing aboard, warned him of the fate awaiting him. He

had sail immediately hoisted on one of the Danish convoy ships, and,

accompanied by his wife, at once returned to Copenhagen.

His

embassy was successful in its mission. By the terms of the marriage

treaty, which is still preserved in the Register House, the Orkney and

Shetland Islands came to Scotland as Margaretís dowry, for her father

had no money to spare her. Arran conducted the princess from Denmark to

Leith in July 1469, where her landing rivalled in pomp and splendour that

of Mary of Gueldres some twenty years before. But in the pageantry of this

gala day the brilliant Arran had no share. During his absence his many

enemies had poisoned the mind of the king against him, and his life was

forfeit. Anxiously and in secret, somewhere near the Shore, his devoted

wife, the Princess Mary, awaited his arrival with the Danish fleet in

Leith Roads, and, stealing aboard, warned him of the fate awaiting him. He

had sail immediately hoisted on one of the Danish convoy ships, and,

accompanied by his wife, at once returned to Copenhagen.

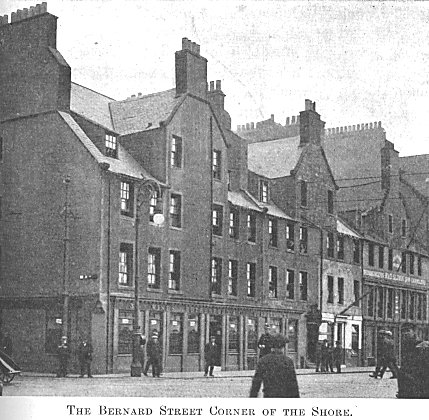

In the Picture Gallery at Holyrood may be

seen four fine examples of Flemish painting of this period, which

originally formed the altar-piece of the Church of tile Holy Trinity,

built by Mary of Gueldres to commemorate her ill-fated husband, James II.

Two of these paintings show full-length portraits of James III. and his

queen, the Princess Margaret of Denmark, whose reception at the Kingís

Wark amid so many demonstrations of welcome on that far-off July day of

1469 forms one of the many brilliant pageants that have been witnessed by

the Bernard Street corner of the Shoreóa street that in many ways still

has about it much of the spell of ancient days, and seems ever to remind

us of our long and close commercial intercourse with the Netherlands in

centuries gone by. In walking here we might almost believe ourselves to be

on the quayside street of some old Flemish port. And how much more real

must the resemblance have seemed in the days before the formation of the

now extensive docks, when the Shore was the only harbour and its quays

were crowded with great ships, while the sky overhead was chequered with

the picturesque outlines of their masts, yards, and cordage.

Arran was not the only great personage of

Jamesís reign to whom Leith offered a ready means of escape when his

life was forfeit. The king, for reasons we do not fully know, had

imprisoned his brother, the Duke of Albany, in Edinburgh Castle. His

friends, knowing his life to be in danger, endeavoured to effect his

escape. Just at this time a French vessel laden with Gascon wine had

opportunely arrived, and was riding at anchor off the pier of Leith. From

the French vessel they sent him two runlets of wine, which, luckily, were

passed by his guards unexamined and untasted. In one of these was a rope

and a waxen roll enclosing a letter intimating that he was to die ere next

dayís sunset, and urging him to make an immediate endeavour to escape,

when a boat from the French vessel would come ashore for him at Leith.

Albany knew he must either do or die. He

invited his guards to join him in doing honour to the wine, whose

excellence was their undoing, for, when they had become tipsy, they were

slain by Albany. He then escaped to the ramparts overlooking Princes

Street. But in the descent by means of the rope his servant fell and broke

his leg. Albany was unwilling to leave his faithful servant to the tender

mercies of his enemies. Being a man of unusual size and strength, he put

him over his shoulders, and, aided by the darkness, carried him safely to

Leith, where a boat from the French trader awaited them. Daylight revealed

the rope dangling over the Castle rock; but by this time Albany was well

on his way down the Firth to his own Castle of Dunbar, from which

he eventually escaped to France.

James III. became more and

more at odds with his nobles as the years passed. They accused him, among

other misdeeds, of debasing the coinage by mixing brass and lead in the

silver money, and making it pass as fine silver. Like other needy kings,

both before and after him, this he had undoubtedly done. That is why a

pound in Scots money gradually deteriorated in value until it was worth

only a twelfth of our British sovereign. This debasing of the coinage

greatly hampered Leith shipmen and Edinburgh merchants trading abroad, yet

King James III. had no more loyal subjects than the people of these two

towns, and, when the nobles imprisoned him in Edinburgh Castle after the

belling of the cat at Lauder Bridge in 1482, it was the provost and

citizens of Edinburgh who were the chief agents in effecting his freedom.

The grateful monarch, believing, as he said, that "we should bestow

most on those by whom we are most beloved," in return for this and

other services granted to the city the deed known as the "Golden

Charter," an incident depicted in one of the picture panels

decorating the City Chambers.

The Golden Charter

conferred many benefits upon the citizens. We are not concerned with these

further than they affected our town of Leith. This Golden

Charter, whose name is an estimate of how highly it was valued by the

citizens of Edinburgh, conferred upon them the right to levy many new

tolls and dues on the shipping of Leith, with the ownership of the land

along the shore for several miles on both sides of the harbour, and all

the roads leading thereto. As in the charter granted by James I., the dues

chargeable to strangers (foreigners) were to be twice those of freemen.

Now the folk of Leith, being "unfree," had to pay the same

double dues as foreigners in shipping goods into the harbour of their own

town. This was not a decree of the city of Edinburgh. It was a provision

of the kingís charter, and that provision was there because the law of

the land in those days conferred rights and privileges on the freemen of

royal burghs like Edinburgh that it denied to the unfreemen of those

burghs and to dwellers in towns like Leith, which were considered unfree

because they were not numbered among the favoured royal burghs.