|

SEVERAL of Leith’s former

industries have passed out of existence in the Port. Thus, for instance,

although Leith does an enormous business in the rectifying, blending,

bonding, and exporting of spirits, yet there are nowadays no distilleries

within the bounds of the Port. Nor does it now contain a single working

brewery. Enormous quantities of ale are exported from Leith to nearly

every country in the world, but none of it is brewed in Leith itself. It

is all made in Edinburgh, which, with its twenty-four breweries, is the

principal centre of the brewing industry in Scotland.

Leith used to possess a

flourishing cane sugar refining business, but it is many a day since the

last of the Port’s sugar refineries closed down. This was the

sugar-house in Breadalbane Street, which in its palmy days carried on an

extensive trade, turning out two hundred and fifty tons of refined sugar

every week. Another industry which flourished in Leith for over two

centuries was the glass-bottle trade. One record shows us that in 1777

there were almost sixteen thousand hundredweights of bottles made in

Leith. The remains of one of the old cones or furnaces may still be seen

at Salamander Street, which owes its arresting name to what was once its

chief industry.

It is interesting to note

that at the present time there is a suggestion of reviving the

sugar-refining and glass-bottle trades in Leith. It is thought that a beet

sugar factory might well turn out a product able to compete successfully

against the cane sugar coming from Cuba and other West Indies sources. It

is also believed that Leith is well adapted for the successful prosecution

of the glass trade, and that a large and flourishing glass industry could

again be established in the Port. Whether these ideas will ever take

practical shape remains for the future to disclose.

Leith’s leading

industries in our own day are shipbuilding, the wine trade, flour milling,

biscuit making, rope making, and the timber trade, and with each of these

we shall now deal in turn.

Shipbuilding

Although the Forth ranks

next to the Clyde among Scottish shipbuilding districts, yet the

shipbuilding industry in Leith has not kept pace with the progress of the

Port. During the first half of the nineteenth century Leith gave promise

of being one of the great shipbuilding centres of the country, but the

Clyde seems to have drawn the trade away from the Port. It has five

shipyards in which vessels up to four hundred feet can be built and

engined, but now most work is done in the branch of ship repairing. It has

six public and two private dry docks, all thoroughly equipped for cleaning

and repairing ships. Vessels can there be overhauled without shifting

port, a great convenience and economy.

One of the oldest

shipbuilding firms in Leith was Messrs. Sime and Rankin’s, which built

several warships in the days of the old "wooden walls." Their

yard, now built on, was opposite the Custom House, but their dry dock,

dating from 1720, and the oldest in Leith still remains, between the Shore

and Sandport Street, and now forms the repairing dock of Messrs. Marr and

Company.

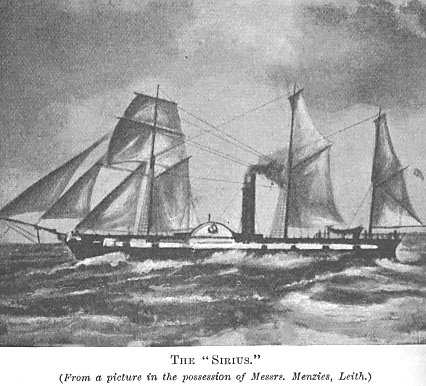

At

the Old Dock gates is the yard of Messrs. Menzies, a firm which has been

established for over a century, and which has sent out many fine ships in

its day. In 1837 Messrs. Menzies built the Sirius, the first

steamship to cross the Atlantic, which she did in eighteen days, arriving

a few hours before the Great Western, which had set out three days

after her. The Sirius ran out of coal, and had to keep her furnaces

going with timber and resin. The picture of the launch of the Royal Mail

steamship Forth, of one thousand nine hundred and forty tons, from

the yard of Messrs. Menzies in 1841—a painting greatly prized by the

firm—shows that the launching of a vessel in Leith in those times, like

the annual departure of the whaling fleet on its perilous voyage, was a

notable event—the day being quite a gala day. At

the Old Dock gates is the yard of Messrs. Menzies, a firm which has been

established for over a century, and which has sent out many fine ships in

its day. In 1837 Messrs. Menzies built the Sirius, the first

steamship to cross the Atlantic, which she did in eighteen days, arriving

a few hours before the Great Western, which had set out three days

after her. The Sirius ran out of coal, and had to keep her furnaces

going with timber and resin. The picture of the launch of the Royal Mail

steamship Forth, of one thousand nine hundred and forty tons, from

the yard of Messrs. Menzies in 1841—a painting greatly prized by the

firm—shows that the launching of a vessel in Leith in those times, like

the annual departure of the whaling fleet on its perilous voyage, was a

notable event—the day being quite a gala day.

The greater part of the new

tonnage launched at Leith is usually from the yard of Messrs. Ramage and

Ferguson. The firm have built about ninety high-class steam yachts, and it

is in connection with yacht building that their name is best known; but,

in addition to yachts, they have also turned out many fine types of

sailing ships, and passenger and cargo steamers, including light-draft

passenger vessels for service in China.

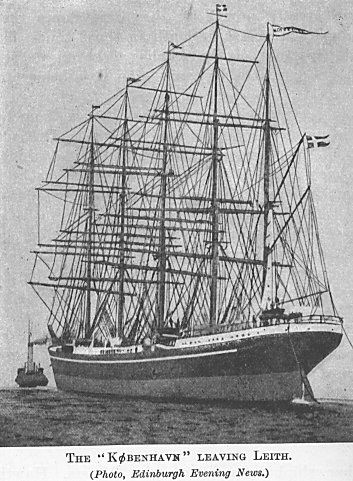

A notable vessel recently

built was the five-masted sailing ship KØbenhavn, built for the

East Asiatic Company, Copenhagen, and which is unique in being fitted with

a 650 h.p. Diesel engine. The vessel is one of the largest sailing ships

in the world. Messrs. Ramage and Ferguson’s engine works have recently

been modernized, and a large number of new machines fitted which enable

them to cope with all branches of marine engineering. The boiler shop is

capable of building boilers of the largest size.

Other shipbuilding firms

are Messrs. Hawthorns, Messrs. Cran and Somerville, Messrs. Robb, and

Messrs. Morton. Since the war a principal feature of the work of all the

firms we have named has been the altering and equipping of the vessels

surrendered by the Germans. In 1919, for instance, Messrs. Cran and

Somerville alone dealt with over thirty surrendered merchant ships. The

Port has also had a large share in refitting for their ordinary commercial

service those merchant ships which the Admiralty had called into its

service, and which had done splendid duty in patrolling, mine-sweeping, or

transport.

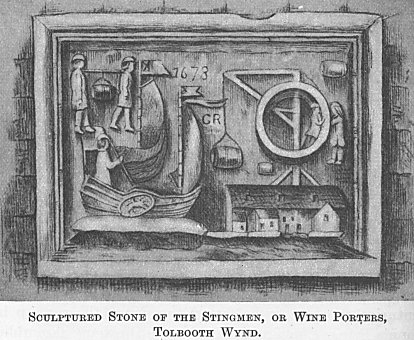

The Wine Trade

As early as the twelfth

century, as we have seen,

the mariners of Leith brought wine

from abroad for the use of the Abbot and Canons of Holyrood. In the days

of the early Stuart kings, after Holyrood had become their court, the king’s

wines all came via Leith. The duties payable by merchants on goods

landed at Leith were exceedingly moderate in those times, for we find that

in 1477 the duty on a tun of wine was only 1s. 4d. Scots (about 5d. of our

money).

In the days of Mary Queen

of Scots, when there was so much coming and going between Scotland and

France, claret from France was the chief wine imported into Leith. This

trade continued to grow for about two hundred and fifty years until the

time of the Napoleonic wars, when it increased greatly in price owing to

the duty imposed on it by the British Government. Sherry from Spain and

port from Portugal then began to be imported in increasing quantities.

In our own day Leith is one of the

chief wine-importing ports of the kingdom, and houses a large number of

wine firms, well known as importers of wines of the finest qualities, and

most of them long established. For instance, in the old ledgers of Messrs.

Bell, Rannie, and Company, who began business in 1715, now over two

centuries ago, are to be found the wine bills run up by Bonnie Prince

Charlie for his gay and brilliant assemblies in ‘Forty-five times. The

chief wines coming into Leith are claret and burgundy from Bordeaux,

champagne from Bordeaux and Dunkirk, sherry from Cadiz, port from Oporto,

and burgundy from Australia. Champagne comes already bottled, but the

other varieties are usually imported in the cask. The export of whisky

from, and the import of wine into Leith, has given it a large trade in

coopering. In his Bride of Lammermoor Sir Walter Scott speaks of

"Peter Puncheon that was cooper to

the queen’s stores at the Timmer Burse (that is, Timber Bush) at

Leith."

When the wine arrives at

Leith it is first clarified and then bottled. It then takes on its bouquet

or aroma, as it would not do if allowed to remain in the cask. In many

parts of Leith there are huge cellars in which are stored, bin after bin,

a huge array of wine bottles, each on its side.

In this position they lie for from ten to fifteen years, their contents

slowly maturing. The temperature of these wine cellars remains the same,

day after day, and year after year, never being allowed to vary from a

certain standard. So extensive are some of these vaults that a visitor to

one of them, after traversing long avenues of bins, may peer out of a

grating into a street a considerable distance away from that at which

he entered. Stores representing fortunes lie unsuspected beneath the feet

of Leithers as they walk their streets.

The oldest building

associated with the wine trade in Leith is the Vaults between Giles Street

and St. Andrew Street, for long years the business premises, as they are

still, of Messrs. J. G. Thomson and Company. This building is locally

known as the "Vouts," a name which, in spelling and

pronunciation, carries us back to the troubled days of Mary Queen of

Scots, when this building seemed to be as gloomy in appearance as it is

to-day, for, as we have already seen, it was then known as the Black Vouts.

The oldest date on the Vaults to-day is 1682, when the great building,

much lower then than now, was either reconstructed or rebuilt. Messrs. J.

G. Thomson began business here in 1785. It was they who raised the Vaults

to their present height. But this historic building had been associated

with the wine trade long years before Messrs. J. G. Thomson’s time, as

is shown by the richly decorated walls and ceiling of the original office,

small in size compared with the present counting-house. The plaster

decoration in the earlier office is very largely symbolical of the wine

trade.

Milling

Leith has long been noted

for flour making, its prominence in this industry being of course largely

due to the fact that it is so conveniently situated for the importation of

foreign grain. In pre-war times Leith imported four hundred and fifty

thousand tons of grain annually.

The wheat used in the Leith

mills is almost entirely foreign, although native wheat also enters into

the mixture. Home-grown wheat is of good colour and flavour, but is soft

and lacking in gluten. Flour made from it alone looks pretty, but is so

starchy and weak that it is good only for scones and other bakers’ goods

known as "smalls." A baker could never get his loaf to

"rise" who made it from flour of this nature. The strongest

wheat we get nowadays is Canadian Springs, and this forms the basis of the

mixture for bakers’ flour. Some Russian and Hungarian wheats are also

strong, but are unobtainable meantime. Leith flour millers also use wheat

from the United States, Argentina, Australia, and Manchuria, while Indian

also comes into the Leith market at times.

When wagons laden with

wheat come alongside one or other of the various Leith mills the wheat is

emptied on to long bands of cloth, which move on rollers, and carry the

wheat into the mill. Then it is caught in elevators, which are just like

the buckets of a dredger, and these empty the wheat into huge tanks called

silos. Below, these silos end in spouts, which the miller opens when he

pleases. He opens two or three together, so as to mix the different wheats.

Then other travelling bands take the wheat to be ground. The wheat passes

through grooved rollers that crush the wheat between them, and then

through fanning machines which blow away the chaff. The wheat is then

ground small between smooth rollers, and, lastly, the flour is driven by a

fan through meshes of very fine silk, and is ready for use.

While the above gives a

general idea of what goes on in a Leith flour mill, it must not be

supposed that the processes of modern milling are as simple as they would

appear to be from the description just given. In reality flour milling is

of a highly technical nature, and a flour mill contains vast arrays of

highly intricate and delicate machinery, all designed to produce the

highest qualities of flour at the lowest possible cost. In spite of the

great advances made in flour milling in the last forty years, millers do

not yet rest content with the position they have achieved. New methods and

new machinery are continually being introduced into the mills. Of all the

improvements made in flour milling the greatest has been the introduction,

in 1881, of steel rollers for grinding the wheat. From the earliest times

until the latter part of last century millstones were used for wheat

grinding. The substitution of steel rollers for these millstones has

produced nothing less than a revolution in flour milling. The millstone is

practically obsolete to-day for wheat-grinding purposes, though it is

still used in the manufacture of Scotch oatmeal.

The

Leith Flour Mills (locally known as Tod’s Mills) in Commercial Street

are the largest in the Port. The original mills were burned down in 1874.

Leithers still remember and speak of this fire as one of the most

destructive in the history of the town, the damage amounting to £168,000.

In the original and also in the rebuilt mills the wheat was ground by

millstones, but in 1882 steel roller mills were installed. Since that date

great improvements have been made in milling machinery, as we have already

said, and the Leith Mills have several times been reconstructed in order

to give effect to these improvements and to keep the mills thoroughly

up-to-date. They have now a capacity of over six hundred thousand bags per

annum. The

Leith Flour Mills (locally known as Tod’s Mills) in Commercial Street

are the largest in the Port. The original mills were burned down in 1874.

Leithers still remember and speak of this fire as one of the most

destructive in the history of the town, the damage amounting to £168,000.

In the original and also in the rebuilt mills the wheat was ground by

millstones, but in 1882 steel roller mills were installed. Since that date

great improvements have been made in milling machinery, as we have already

said, and the Leith Mills have several times been reconstructed in order

to give effect to these improvements and to keep the mills thoroughly

up-to-date. They have now a capacity of over six hundred thousand bags per

annum.

Junction Mill is a flour

mill and also an oatmeal mill. It belongs to the Scottish Co-operative

Wholesale Society, who took it over from Messrs. John Inglis and Son in

1897. The capacity of the flour mill is about fifteen sacks per hour, and

in 1920 its production Was 123,808 sacks. In the same year the oatmeal

mill produced 28,504 sacks of oatmeal, all the oats used in the mill being

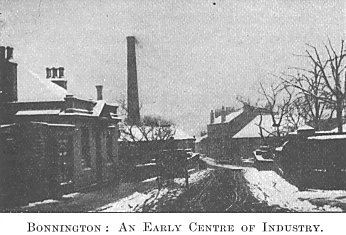

Scottish. Swanfield Mill in Bonnington Road is a flour mill, while Messrs.

Inglis have a large oatmeal mill at Bonnington. These mills, like the

others already mentioned, possess the latest types of miffing machinery.

Biscuit Making

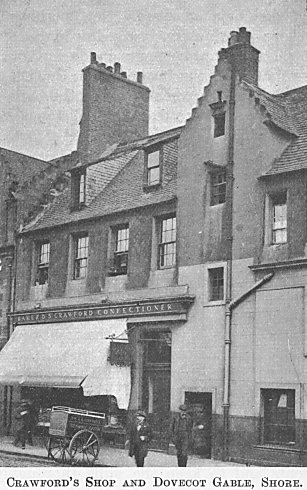

In the firm of Messrs.

William Crawford and Sons Leith possesses the oldest of the Scottish

biscuit manufacturers. It was in 1813 that Mr. William Crawford founded

the business in a small shop at the Shore of Leith, which, enlarged and

modernized, is still occupied by one of his descendants. It immediately

fronts the spot where in 1822 George IV. landed on his visit to Scotland.

As every fresh step in the science and art of bread and biscuit making,

and every improvement in machinery and method, were welcomed by the

founder of the firm, increasing trade quickly outgrew the capacity of the

original small premises at the Shore. Modern works were established in

Elbe Street. These have been frequently extended and largely rebuilt as

the firm progressed, and no trouble or expense has been spared to keep the

works equipped with all that is latest and best in machinery and

appliances. Crawford’s shortbread and Crawford’s biscuits have

attained a national reputation, and have become widely known in some of

the remotest parts of the globe. The factory affords employment to

hundreds of Leith men and girls.

Timber

The time when our own

country could supply its needs with regard to timber is long since past.

So many are the uses to which timber is nowadays put, and so many

different kinds are needed to meet all the requirements of our various

industries, that most of the timber now used in Britain comes from abroad.

Before the war we were importing over 11,000,000 tons of timber annually,

of which 7,000,000 tons came from North Russia (the Baltic States,

Finland, and Archangel), Sweden, and Norway, 2,000,000 tons from Eastern

Europe, and only slightly over 2,000,000 tons from countries outside of

Europe (mainly Canada, United States, South America, Australia and New

Zealand, India, the West Coast of Africa, the West Indies, Mexico,

Honduras, etc., and Japan).

These figures show that our

country in normal times is dependent on the Baltic and White Seas for

seven elevenths of its timber supplies, and make it quite clear how Leith,

with its advantageous position with regard to Russian, Swedish, and

Norwegian ports, has become one of the chief timber ports in the United

Kingdom. An important factor in the growth of Leith’s timber import lies

in the connection between the coal and timber trades. North Russia,

Sweden, and Norway have no coal supplies of their own, and as Leith is

situated near coalfields its ships have thus at hand for their outward

voyage exactly the kind of cargo which is required.

The chief timber importers

and sawmillers in Leith are Park, Dobson, and Company, Eastern Sawmills,

Easter Road; John Walker, Lochend Road; Garland and Roger, Baltic Street;

Fergus Harris, Morton Street; and John Mitchell and Company, Leith Walk.

During 1912, 1913, 1914, and 1920 these firms imported timber as follows:

1912, 90,412 tons; 1913, 100,941 tons; 1914, 80,096 tons; 1920, 117,245

tons.

The timber used to be

imported into Leith in the form of logs, roughly squared by means of the

adze; but with the introduction of machinery, however, the timber is now

brought into the Port in the shape of sawn planks, deals, battens, and

boards of various sizes, the amount imported in the log being very small

nowadays. Indeed, so great has the change been in the form in which timber

is imported that sometimes material is brought into Leith in a fully

dressed state. Thus, especially from Sweden, we get flooring boards,

doors, window frames, and mouldings of every kind, all ready for the use

of the joiner and carpenter.

The wood brought into Leith

from the Baltic and White Sea ports is nearly all of the pine family, and

is known in the timber trade as red or yellow deal. Red and yellow pines

are also imported into Leith direct from Canada and the United States.

While the principal timber trade of Leith is connected with the woods just

mentioned, known as soft woods, it has also a share in the hard wood

branch of the trade. Of the hard woods the chief are oak (from the Baltic,

America, and Japan), mahogany (from Mexico, Central America, the West

Indies, and West Africa), teak from Burma, and ash from Japan. These hard

woods are not shipped to Leith direct—except those which come from the

Baltic—but reach it via some other port, such as Glasgow or Liverpool.

Rope, Twine, and Sail

Making

The making of ropes, twines, and

sailcloths forms one of Leith’s largest and most specialized industries.

The well-known Edinburgh Roperie and Sailcloth Company was founded in

Leith in 1750 by a number of Edinburgh and Leith merchants who combined to

advance the interests of the industry. The company was encouraged in its

enterprise by obtaining at reasonable rates

grants of land at the north-east corner of the Links. From a small

beginning the trade has now reached immense proportions, the enormous

development of the Company’s business having given to Leith a celebrity

in the manufacture of ship rigging unsurpassed in any country in the

world. During the hundred and seventy years that have elapsed since the

establishment of the firm, the scene of their earliest operations has from

time to time been extended, till now the works in Bath Street cover an

area of twenty-five acres.

In 1805 the company

established the Malleny Mills, eleven miles from Edinburgh, where abundant

supplies of water for bleaching purposes existed, and where the flax and

yarns were prepared for the manufacturing operations of the Leith works.

These mills were used for this purpose for many years, until the increased

supply of water brought in by the Edinburgh and District Water Trust

enabled the company to concentrate their whole works in Leith. About the

same time the works at Glasgow (where fishing lines, etc., were

principally made) were also transferred to Leith, so that the whole

business is now housed in the Port, local control and economical

management being thus secured.

It may be mentioned that an

uncle of William Ewart Gladstone was formerly a managing partner in the

business, while Sir John Gladstone, the father of the great statesman,

gained his earliest commercial experience in the counting-house of the

Edinburgh Roperie and Sailcloth Company, of which he was afterwards one of

the leading partners.

At the present day the

business is composed of two great divisions—cordage and sailcloth

making. In the cordage departments are manufactured: (1) Ropes of all

descriptions in Manila, New Zealand, and Russian hemp, and in jute fibres.

Yacht Manila ropes, steamer and railway ropes, and tarred trawl ropes for

trawl fishing are manufactured, but a very large part of the company’s

cordage business consists in the manufacture of large Manila ropes—up to

twenty-four inches in circumference, and in length up to two hundred

fathoms— used as towing ropes for large ships. (2) Fishing-lines for

deep-sea, coast, and river fishing. These are distributed over the entire

fishing world. (3) Shop twine. (4) Binder twine, used by self-binding

reaping machines. Large consignments of the twine are sent from Leith

Docks to the Canadian harvest fields. (5) Trawl twine, used in the

manufacture of trawl nets. This twine is made of the finest Manila fibre,

as none but the best of materials will withstand the strain of trawl-net

fishing.

In the sailcloth

departments are made as many as ten different brands of sailcloth, the

Leith sailcloth having attained an enviable reputation among ship-owners

and being known the world over. With the place of the sailing ship,

however, taken by the steamer the output of sailcloth for ships’ sails

has fallen off a good deal, and the company has had to look in other

directions for the disposal of its manufactures, with the result that in

addition to sailcloth it now manufactures large quantities of canvas, etc.

|