|

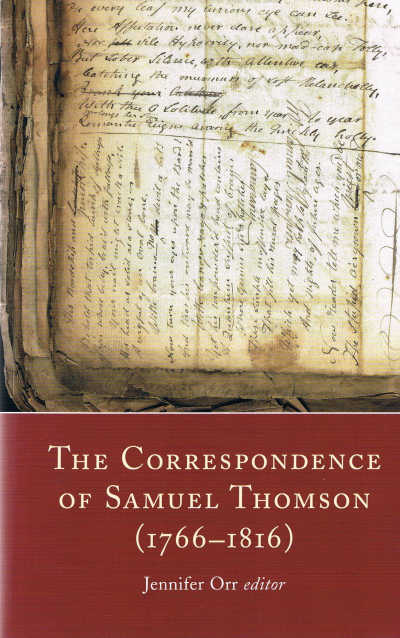

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

This

has been a fun book to read and writing the book review has been equally

enjoyable! It weaves an interesting story of a group of Irish poets

corresponding with each other. A big topic of conversation among some of

them is the Scottish poet Robert Burns. The poets write about books, buying

and borrowing them, “the expense of postage”, and ‘the selfish consideration

that the sooner I write to you, the sooner I will be gratified with the

receipt of a letter from you”. Naturally their writings are about each

others books or poetry and the political situation where writing by code

became, for obvious reasons, the order of the day for some of them. This

has been a fun book to read and writing the book review has been equally

enjoyable! It weaves an interesting story of a group of Irish poets

corresponding with each other. A big topic of conversation among some of

them is the Scottish poet Robert Burns. The poets write about books, buying

and borrowing them, “the expense of postage”, and ‘the selfish consideration

that the sooner I write to you, the sooner I will be gratified with the

receipt of a letter from you”. Naturally their writings are about each

others books or poetry and the political situation where writing by code

became, for obvious reasons, the order of the day for some of them.

The relationships of the inner circle seems to

border on the ‘you buy mine and I’ll buy yours” scenario or the “here is a

list of subscribers for your book or your poem, and I hope you can do the

same for me” idea. One poet interjects a time limit on how long his friend

can borrow his book, three months actually, and it must be returned by

August 1st which comes and goes – another reminder is sent - and

then another later on. I have found no record the book was ever returned.

Lesson? Be careful who you loan your books to, even good friends, much less

your family! The correspondence of this circle of bards centered on Samuel

Thomson’s cottage, Crambo Cave. Thomson was the one at the center of the

poets group and was described as “the father of a northern school of Irish

poets.”

But all is not fun and games in this book by

Jennifer Orr, and soon tension builds concerning the political climate in

Ireland. Before too long a few of the poets find themselves living in

Philadelphia or Charleston or other countries for their own safety as well

as that of their families. Unfortunately an execution or two takes place,

cooling the radical arguments about freedom from some of them, Thomson

included. The poetry they write raises eyebrows and the government takes

action against some of them after they publish their poems in newspapers

like the Northern Star, a radical United Irishmen publication which

has its press destroyed. Thomson is described as “practically the poet

laureate” of the newspaper.

His friend James Dalrymple felt the Irish

political situation would mean “much blood (to) be spilt before you enjoy

political freedom and whether it is worth the sacrifice you in Ireland must

judge.” Again, some in the group paid with their lives! The 1798 Rebellion

was a trend setter, and they were aware of the thin ice they walked upon

leaving Thomson and others in the circle more cautious about publishing

their writings from then on. The United Irish Movement was not so united but

the United Kingdom was.

Editor, Dr. Jennifer Orr

For Burnsians like myself, lay people, I found

the correspondence about Burns to be exciting because these poets were

contemporaries of his and their comments make the book come alive as they

discuss Burns just as you and I would discuss a friend among our own circle

of acquaintances. Let’s take a look at a few instances regarding Burns and

these poets as we skip among the references.

Burns received a couple of letters from Thomson

discussing political subjects, thus reminding us that both were radicals at

times.

Samuel Thomson found his way from Co. Antrim to

Dumfries in 1794 to meet with Burns in his home and he leaves with several

original poems by Burns, among them was Clarinda, Mistress of My Soul.

You have to wonder what political topics were discussed by these two

outspoken men.

Packet boat owner James Lemon carried a number

of parcels to Burns from Thomson, but unfortunately there is no mention of

what they contained.

Here is an interesting item. Did Burns dip snuff

? Either he did or he passed it on to someone because mention is made of

suggestion to “send him a pound of snuff known by the name of Blackguard.

Lundy Fool in Dublin is the famous Manufacturer of it.” This occurred in

1791 and we know Thomson also sent another packet of snuff to Burns in March

1794. (It is reported that Burns requested the first gift of snuff after

giving Thomson a copy of Fergusson’s POEMS.)

John Rabb, another Irish poet, writes Thomson

asking “will you call and tell me where Burns lives now?” as Rabb is

interested in opening correspondence with Burns.

Evidently James Hogg was not the only one who

felt he could replace Burns as Thomson would later market himself as the

successor to the Scottish bard just as Burns felt he could establish himself

as Fergusson’s successor.

Our old friend William Magee shows his ugly head

in the book as a Belfast printer working with Thomson and other poets

publishing their works. Those familiar with Magee know he pirated the works

of Burns and published them in Ireland with poor Burns never receiving a

penny. The greedy Magee got it all!

Burns actually met Irish poet Thomas Sloan while

traveling from Ayrshire to Ellisland and a delightful friendship developed.

Burns later had to inform Sloan that he was unable to resolve financial

assistance Sloan needed when Burns turned to John Ballantine on behalf of

Sloan.

John Gillespie visited Burns carrying snuff from

Thomson. “I’m just going to scold Mr. Burns this mail”, Thomson wrote, but

nothing in Thomson’s letters backs up his claim of scolding Burns. Thomson

does pen the words of Italian poet Ariosto at the end of this letter saying,

“No form so graceful can your eyes behold / For nature made him and

destroy’d the mould.”

In a post script, Luke Mullan writes this to

Thomson: “I have seen Mr. Burns and spoke to him…I endeavoured to learn as

much about his character as possible - he is not much respected in Dumfries

on account of his infidelities to his wife - but as an officer of the excise

he is said to be very humane to poor people. I believe he writes little now

- he offers some to the Dumfries Papers and is not accepted - so little are

great men thought in their own country and in their lifetime…”

I must conclude with these little gems about

Burns and refer you to the book where the beat goes on and on and moves,

according to John Gray, from “adulation to discord”.

This is a magical book, and Jennifer Orr has

done a masterful job of portraying the relationship between these Irish

poets as well as their relationship to Burns in their correspondence. In

response to an email of mine, Jennifer wrote, “I too was amazed at the

reflections on Robert Burns contained within and, particularly, the idea

that Thomson may have had a key role in shaping the Bard’s reputation in

Ireland.” Indeed he did. BUT, you should remember there is much more to this

book than just the relationship between the Irish poets and Robert Burns.

Much more! (FRS: 5.4.12)

Now I want to share with

you some of Jennifer’s thoughts which will be a great asset to you regarding

The Correspondence of Samuel Thomson. In an email dated April 30th,

Jennifer wrote…

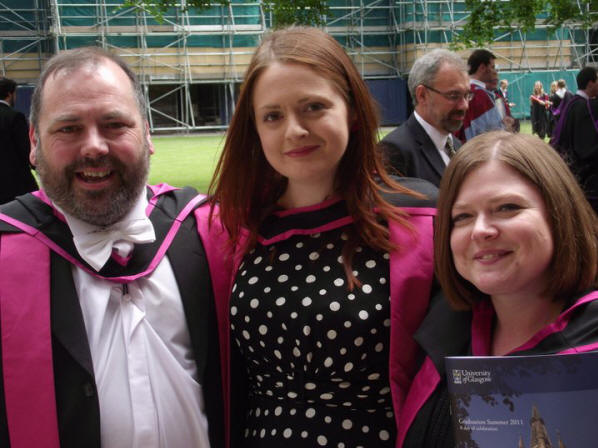

L-R: Dr. Gerard Carruthers, Dr. Jennifer Orr

upon receiving her PhD, and Dr. Rhona Brown, all from the University of

Glasgow.

Regarding your questions for the article, my

attraction both to Burns and the Ulster poets was strongly rooted in a

shared sense of mixed identity. Scottish and Irish heritage has always been

strongly bound up together in Ulster and, like Samuel Thomson; I have always

had a strong sense both of my Irish and Scottish heritage. Names within my

family include Shields (which I'm told is a Donegal name), Bell, Campbell,

Mechan and Duncan. Most of them had been around in Ulster for centuries but

the latter were coal merchants from Scotland and moved to Ireland in the

Victorian ear when Belfast became a central industrial city within the

British Empire.

We grew up

in Bangor, County Down, just 12 miles across the North Channel from Scotland

where the hills of the Galloway peninsula can be seen on a clear day. My

grandparents took my mother and aunt on holiday to Ayrshire, visiting Robert

Burns's cottage in Alloway, which seemed to be a frequent site of pilgrimage

for Ulster holiday makers. Robert Burns was as natural a part of my literary

heritage as William Shakespeare or William Yeats. I had little trouble

understanding the Scots language as I had heard variants of it spoken in

rural parts of Ulster.

While I was an undergraduate at Oxford, I studied Anglo-Saxon and medieval

literature but when it came to researching my undergraduate thesis, I

fancied doing something different and closer to home. I decided to write on

the topic of Irish poetry and to explore something that was personal to me.

My aunt Dr Carol Baraniuk had taken a secondment from her job as a school

teacher to work on a project with the Ulster Scots Academy at Stranmillis

College Belfast and told me of an exciting tradition of eighteenth- and

nineteenth-century Ulster poets who wrote in the language of the people.

She was particularly interested in the poet James Orr and was about to

embark on a PhD at the University of Glasgow. She mentioned that Orr's

friend and fellow poet Samuel Thomson was also an interesting figure who had

corresponded with Robert Burns.

The research that we were undertaking coincided with an exciting resurgence

of Scottish Literary studies at the University of Glasgow on the approach to

the Bicentenary of Robert Burns's birth. In May 2005 I traveled to Glasgow

to meet with Professor Gerry Carruthers who agreed to supervise a doctoral

thesis on Samuel Thomson pending my successful graduation from Oxford. Two

years later, I was successful in obtaining funding and from 2007 played a

full and active role in the exciting intellectual environment of the

Glasgow's Department of Scottish Literature, where I was also able to gain

teaching experience while undertaking research. Following my viva in May

2011, I produced The Correspondence of Samuel Thomson.

Five years ago, even those familiar with Irish literature would have

struggled to name more than five Ulster poets. Heaney, certainly. Maybe

Michael Longley and John Hewitt. In fact, it has been a commonly-held belief

that the Romantic period missed Ulster completely. While Robert Burns was

active in Scotland, why should there not have been a similar movement in

Ulster, particularly when the newspapers were full of revolutionary and

nationalist verse? Many of Thomson's poems are as good as Burns's and some

might even be better, like the masterful political allegory 'To a Hedgehog'

and 'O Scotia's Bard, my muse alas!', Thomson's skilful parody of Burns's

'Does Haughty Gaul Invasion Threat?

To a

Hedgehog

Samuel Thomson

Thou grimmest far o gruesome tykes

Grubbin thy food by thorny dykes

Gude faith, thou disna want for pikes

Baith sharp and rauckle;

Thou looks (Lord save's) arrayed in spikes,

A creepin heckle.

Sure Nick begat thee, at the first,

On some auld whin or thorn accurst;

An some horn-fingered harpie nurst

The ugly urchin;

Then Belzie, laughin like to burst,

First caad thee Hurchin.

Fowk tell how thou, sae far frae daft,

Whan wind-faan fruit be scattered saft,

Will row thysel wi cunning craft

An bear awa

Upon thy back, what fares thee aft,

A day or twa.

But whether this account be true

Is mair than I will here avow;

If that thou stribs the outler cow,

As some assert,

A pretty milkmaid, I allow,

Forsooth thou art.

Now creep awa the way ye came,

And tend your squeakin pups at hame;

Gin Colly should oerhear the same,

It might be fatal,

For you, wi aa the pikes ye claim,

Wi him to battle.

Both poets

shared a belief in the common humanity of all men regardless of class status

and exploited their hybrid knowledge of the Scots and English languages to

contribute to the rich cultural tapestry of Scottish and Irish identity

within a dislocating British constitutional context. Thomson consolidated a

group of writers during the Irish revolutionary period 1790-1798 as a means

of resisting the British state but once the Anglo-Irish Union came about in

1801, he modified his tactics to preserve Irish identity by promoting her

unique artistic and cultural status. Thomson was deeply in tune with the

print culture of his day and he knew that cultural identity was a complex

and unstable concept and could include a range of identities. His pragmatic

poetic response to turbulent historical events preserved a sense of Irish

dissenting nationalist culture that might have been swallowed into the

cultural stereotypes of Prostestant-unionist and Catholic-nationalist which

are so familiar to us from the troubled Twentieth Century.

Sorry - a bit of an essay for you here - but hopefully it will be useful!

Thank you, Jennifer, for

sharing your book as well as yours thoughts with us. This is a subject that

was begging to be presented. |