|

Edited by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Greater Atlanta, GA, USA

Email: jurascot@earthlink.net

My good friend Patrick Scott, retired

professor at the University of South Carolina, has a way of writing

articles that show up like gifts under a Christmas tree, but there is

one huge difference - his gifts show up more than once a year! Such is

the case with this article on the Bard that will bring you joy and

tickle your heart. I could write much more on Patrick, his adventures

and publications, but all I need do is refer you to the many articles in

the Robert Burns Lives! index he has posted over the years. Take your

pick of them or read them all and you will be a better person for

learning about this amazing husband, father, grandfather, scholar,

teacher, professor, author, and noted speaker, the many shoes he has

filled over his career. You are a lucky person indeed if he is listed

among your friends. Enjoy this article and know there will be others

from this gifted and talented writer in the future. (FRS: 7.10.20)

Reading Burns in Installments: the Hidden

History of Part-Publication

By Patrick Scott

About a year ago now, an old friend, a very

knowledgeable antiquarian bookseller, emailed me about a rare Burns

item:

I attach a description of a

set of the works of Robert Burns, issued in 17 parts or fascicles. Although

I have probably seen more sets of Burns’s works than I have had hot dinners,

I have never encountered a set issued in parts. Nor could I find a bound set

made up from these parts. Egerer’s bibliography of Burns has remained

reasonably reliable over the years, but this also seems to have been a copy

or set that he missed.

The dealer had done his due diligence: this

particular set (which he identified as the “People’s Edition,” published

by Virtue of London, ca. 1910) is indeed unrecorded elsewhere. Because

standard library cataloguing relies on title-page information, total

page numbers, and size, the major online catalogues do not usually tell

you which libraries might have a Burns edition issued in parts rather

than as a bound volume. And, with only a few exceptions, J. W. Egerer’s

standard Burns bibliography does not usually record if an edition was

ever issued in separate parts.

While it is by no means implausible that a dealer at the upper end of

the book market had never encountered Burns-in-parts, this publication

pattern was quite widely adopted throughout the nineteenth century. The

most famous example is the novels of Charles Dickens, beginning with

Pickwick Papers (1836-1837). Partly because of other Burns projects,

discussed below, I’d recently come across two other sets of

Burns-in-parts, and the email made me look for more.

Publication in parts broadened the market, by allowing people with

modest disposable income to buy expensive editions installment by

installment, spreading the cost over a period of up to two years. Even

white-collar workers in the late Victorian period might earn only five

or six pounds a month (a hundred shillings, “thirty bob a week”). A book

that might cost perhaps thirty shillings, or even two pounds, in

complete form, was much more affordable when purchased part by part,

month by month, maybe in 8 thick parts at five shillings each, or in

fifteen parts at two shillings, or maybe in 25 magazine-like parts for

one shilling a month.

The problem for collectors is that, once a purchaser had completed the

set, the parts would normally be bound up in book form. Separate parts

in paper covers are easily damaged, and libraries either sent the parts

for binding, when the covers themselves would usually be discarded, or

eventually had to discard the parts themselves. If a set was incomplete,

or some issues got damaged, the likelihood of the remaining parts being

preserved is very low—individual parts, like old magazines, tend to be

kept for a while, and then thrown out. If the odd wrappered part got

saved as a curiosity or collectible, you are more likely to find it now

in a junk shop or on eBay than in an antiquarian bookstore, and such

separate parts are easy to cannibalize, because the illustrations can be

framed or sold separately. Very few complete sets of Burns-in-parts seem

to survive, or at least very few seem to be recorded in libraries. This

brief survey, based on material in the Roy Collection, is intended to

give a general overview, but it will inevitably be selective and

incomplete. There must, however, be individual parts, or even complete

sets, lurking unregarded in the personal collections of some longtime

Burnsians and Burns collectors, and if so, I’d be pleased to hear from

them.

Publishing in parts did not originate with the Victorians. It was used

in the 18th century for expensive illustrated works, like Francis

Grose’s Antiquities of Scotland. Bill Dawson pointed out a few years ago

that the first publication of Burns’s “Tam o’ Shanter,” in 1791, in

Grose’s second volume, had always been misdated. Burns scholars had been

using the date when Grose’s completed volume was advertised, in April

1791, citing the poem as first published in March in an Edinburgh

newspaper, but the part of the Antiquities with “Tam o’ Shanter” had

appeared at least two months earlier, perhaps more (Dawson).

Booksellers also used part-publication at the other end of the market.

The earliest part-issue of Burns in the Roy Collection is a little

duodecimo printed in Paisley by J. Neilson, in 1801-1802. Ross Roy liked

to recount how he bought it in the Gorbals many years ago for thirty

shillings (i.e. £1.50: Roy and Scott, 2010). Each of the 36-page

sections or gatherings of the book has been put into its own plain paper

wrapper, and when the buyer stitched them roughly together in two

volumes, he left these temporary wrappers intact. There are no separate

title-pages for the parts: each part ends or takes up abruptly wherever

the page ends, even in the middle of a poem. Without external evidence,

it’s impossible to prove this edition was sold in separate parts, but

there seems no other explanation for the separate paper wrappers (cf.

Sudduth, p. 43).

This was not a unique example. Egerer notes an edition published in

Newcastle in 1818 as being issued in parts, and that four parts, from at

least twenty-six, survive in the Mitchell Library collection (Egerer,

209, p. 134, though the part issue is not noted in Fisher, p. 65). The

bound volume of this edition in the Roy Collection, like the one Egerer

describes in the Carnegie Library, Ayr, had been bound up from the

separate parts, with the stab holes still visible in the inner margins

(as described further below).

Part-issue not only spread the cost for the buyer, but also spread out

the work for the printer, and spread out the investment for the

publisher, who could begin to recoup what he had spent on the early

numbers of a book before the bills came in on the later sections. From

the 1830s on, when new editions of Burns often involved well-known

editors, it also spread out the deadlines for the editorial work as

well. All three of the major editions from the 1830s came out in parts

or series, rather than being published in one fell swoop. Allan

Cunningham’s edition was planned as a series of six volumes, one a month

from January to June 1834, each of about 300 pages, with two

illustrations, at 5 shillings a volume (Egerer, pp. 169-172). In the

event, Cunningham had extra material, and needed eight volumes, with

vol. VII appearing in October, and vol. VIII in December. The same

engravings, by D.O.Hill and others, were also published separately, in

three parts, on much larger pages, at 15 shillings for the set, or in a

limited special edition of 25 copies only, on India paper at 22s. 6d.

(advertisement in The Examiner, April 12, 1835).

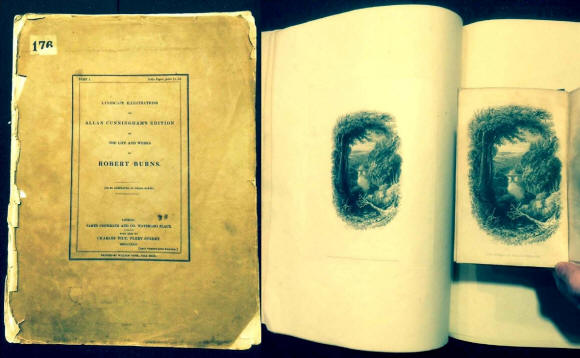

D. O. Hill, Landscape Illustrations to Allan

Cunningham’s edition (London, in parts, 1834-1835)

Cover for part 1 (left); “The Braes of Ballochmyle,” with the same image

from Cunningham, vol. II (right)

James Hogg’s edition had been planned

earlier, in 1831-32, but languished till Cunningham’s rival edition was

announced, when it was rushed to press. While the volumes were similar

in format to Cunningham (both were small octavos), the Hogg edition was

first issued in paper-covered parts, each of 144 pages, with an engraved

illustration. When it was announced, in January 1834, it was to be

edited by Hogg alone, and to consist of twelve parts, at 2 shillings

apiece, which would then also be available as five volumes, at 5

shillings each. The first part came out in March (and was reviewed in

The Scotsman on March 26), but sharp criticism in the London papers led

the publisher, Archibald Fullarton, to bring in William Motherwell as

coeditor, and it is now generally cited as “Hogg-Motherwell.”

Publication thereafter was irregular, with the final sections, parts

11-13, including Hogg’s Memoir of Burns, not published till 1836 (Egerer,

pp. 167-168). By then, both Hogg and Motherwell were dead. There is a

set of the original parts in the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, which shows

that the critical attack on the first number led to a ‘cancel’ or

substitute page before the edition was published in volume form (Fisher,

p. 27): in part 1 of the original issue (vol. 1, p. 125), Hogg’s note

about the subject of “The Lament occasioned by the Unfortunate issue of

a Friend's Amour,” which commented on Alexander Cunningham being jilted

by his “darling sweetheart” (“she acted a wise part. H.”) had to be

withdrawn, and a new note by Motherwell, linking the poem instead to

Jean Armour, was substituted.

When bound, the Cunningham and Hogg-Motherwell editions look very

similar, and they were competing for the same elegant, middle-class

market, but buying the Hogg-Motherwell edition required much less

disposable income. A full set of Cunningham would have cost forty

shillings or two pounds, and to keep up with the new volumes required

the ability to spend five shillings each month for six months, but a

full set of Hogg-Motherwell could be had for two thirds of the price,

and the part issue meant that purchasers need only fork over two

shillings at a time—manageable for many more people. For comparison, the

four volumes of the Currie edition (1800) had cost thirty-one shillings

and sixpence, and the three-volume Pickering (Aldine) edition (1839),

with just the poems, not the letters, cost fifteen shillings.

Most discussion of part publication stresses the importance for readers

of simultaneity, where publication of each part was a communal news

event, and a whole cohort of readers were all reading the same stage of

a serial publication at the same time, rather like people all watching

the same first-run television series. It was this simultaneity that gave

Dickens’s novels their enormous impact in early Victorian culture;

everyone had read the same stage of the story the same month, and no one

knew quite what would happen next. The part publication of Burns could

involve something of this (as for instance when a publisher advertised

that a new discovery would feature in the next number or when critics

responded to specific numbers of a work during publication), but because

most of the material in any Burns edition was already well known, the

sense of each installment as a special event or revelation played much

less of a role than in the serial publication of a novel. In fact,

another publishing development, stereotyping or the making of reusable

casts or plates of the typesetting, meant that both the Cunningham and

Hogg-Motherwell editions went on being reprinted again and again,

without revision, for many years after the original publication sequence

was over. While the Cunningham edition was soon also reformatted to make

a one-volume edition, and also soon pirated by other publishers (with

each resetting and pirating introducing some additions and revisions),

the Hogg-Motherwell edition was reprinted multiple times in its original

small quarto format from the same stereotype plates: Egerer records

reprints in 1835, 1836-41, 1838, 1840, 1848, and 1852. At least twice,

the edition was also reissued in parts: the Roy Collection has

part-issues, dated by the advertisements on the back covers, from the

1850s and amazingly the 1880s. Though they lacked the illustrations,

these reissues were even cheaper than the original: you could get the

reprinted part-issue in fifteen 120-page parts (each of 120 pages), at a

shilling a part, or in 30 60-page parts at sixpence a part.

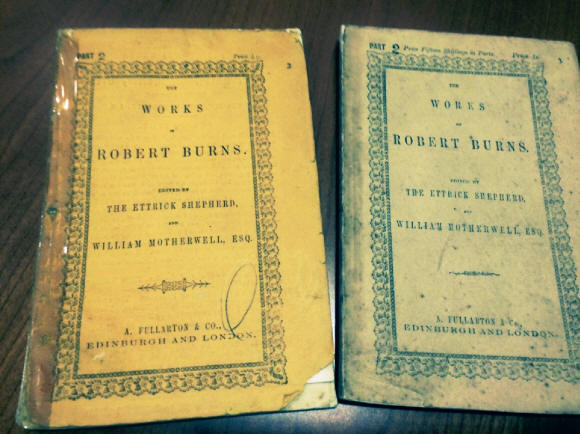

The later sixpenny and one shilling variant

reprints in the original format:

The Ettrick Shepherd and William Motherwell, The Works of Burns

(Glasgow, in parts, 1834-1836)

The third of the major Burns editions from

the 1830s was also published in several segments, if not formally in

part issue. This was Robert Chambers’s first version of what became,

through two later reworkings, the great Chambers-Wallace edition. As

Chambers and his brother William first published it, however, it

consisted of three works: Poetical Works, 1838; Life, 1838—an expansion

of Currie; and Prose Works, 1839—incorporating a lot of Cromek. The

parts were advertised as each being “complete in itself,” but they were

part of a series that W. and R. Chambers were publishing, first called

“The Standard Library,” but soon retitled “The People’s Edition.” The

Chambers brothers touted it as “The Cheapest Series of Publications Ever

Issued from the Press,” tall pamphlets on cheap paper, with

double-columns of cheap print. Other authors included Walter Scott (out

of copyright poetry only), Allan Ramsay, Francis Bacon, and William

Paley, and prices ranged from six pence up to two shillings, depending

on the length of the specific volume. The three parts could be bought

for 2 shillings, 1 s. 2 d., and 1 s. 10d, respectively, which meant the

complete Chambers Burns was only 5 shillings, an eighth the price of

Cunningham (advertisement in Caledonian Mercury, January 1, 1839).

Even in the early Victorian period, part-publication was still being

used to market more expensive large-format illustrated books. Full page

engravings or lithographs could not be printed in the same operation as

typeset material, and in some Victorian illustrated editions, the

illustrations take priority over the text. Sometimes, as the Cunningham

edition indicates, purchasers even wanted the illustrations by

themselves separate from the text. A good example of illustrations

taking priority is the two-volume collection, The Land of Burns, which

also had engravings by David Octavius Hill, along with text credited to

Prof. John Wilson (“Christopher North” of Blackwood’s Magazine), who

wrote the introductory essay, and by the ubiquitous Robert Chambers,

moonlighting for a publishing rival, Blackie and Son of Glasgow, who

provided descriptions of the landscape scenes and portraits. Wilson

dragged his feet, and Chambers’s text, and the illustrations, were

nearly finished and ready for publication before Wilson was shamed into

starting (Blackie, p. 39). The work was published both in a large-paper

version (40 cms in height), and in a still-impressive regular issue (27

cms.). Though the title page, and so most library catalogues, record the

publication date as 1840, it was actually published over a three year

period between November 1837 and November 1840, in 23 parts, at 2

shillings a part (Blackie, pp. 35, 114; cf. Egerer, p. 185). The Roy

Collection does not have any of the wrappered parts, but one of the

bound sets contains the giveaway sign previously mentioned that it has

been bound up from the part-issue: about a quarter-inch in from the

spine on each page is a line of several small pin-holes, indicating that

before the sections were stitched through the spine to form the book,

they had been “stabbed,” or stitched, through the pages, for

part-publication (cf. Dawson, p. 109). The old thread had been removed

in the rebinding, but the stab-holes remained. The same publisher

recycled many of the Hill illustrations again for a new edition of

Burns’s Works, again prefaced by Wilson’s essay (Egerer 450, p. 191).

This too was first issued in two shilling parts (this time 21 parts,

1842: Blackie, p. 115), before being issued in two volumes (1843, 1844).

For this edition alone Egerer lists eighteen reprintings. Blackie notes

that it was reissued in 1853 as 25 one-shilling parts, plus 8 additional

parts with the illustrations (Blackie, p. 117).

It should, by now, be no surprise to find that Robert Chambers’s next

Burns project, expanding and rearranging his edition of 1838-39 as a

four-volume edition, The Life and Works of Robert Burns (1851-1852), was

also first issued as separate parts, in blue printed paper wrappers, at

2s. 6d. each (cf. Egerer 540, p. 205). This was a price, and included in

a series (“Chambers’ Instructive and Entertaining Library. A Series of

Books for the People”), that would have justified simply reusing earlier

content, but Chambers had added quite a lot of further material, both

poems and letters. Chambers himself would revise it one more time, as

“the Library Edition,” again in four volumes, at 5 shillings each

(1856-1857: Gibson, p. 69; Egerer 594, pp. 216-217), adding a little new

material; this is the edition usually being cited as “Chambers” by

Victorian Burnsians before William Wallace overhauled it yet again for

the 1896 centenary.

But the editions described so far all pale in comparison with the two

great part-issues of Burns from the 1860s and 1870s. Both edited by

clergyman, the Rev. Dr. Peter Hately Waddell of Glasgow and the Rev. Dr.

George Gilfillan of Dundee, these were great big books that in volume

form had colorful heavily-gilt-stamped cloth bindings much like

Victorian family bibles. The involvement of ministers, even eccentric

ministers, and the respectable appearance of the series is significant

in a period when the unco guid were still often suspicious of Burns and

the Burns movement (cf. Whatley, pp. 87-92). Waddell’s edition even used

the same technology for illustrations, chromolithography and steel

engraving, that was often used for illustrated bibles, and in turn

publishers like Cassells were issuing family bibles in parts, so as to

expand the market by increasing their affordability. Waddell’s edition

is always dated from the title-page as 1867 (cf. Egerer 701, pp.

234-235), but in fact it was issued in large-format (magazine style)

parts, in vivid orange paper covers, over a period of 25 months (April

1867-April 1869).

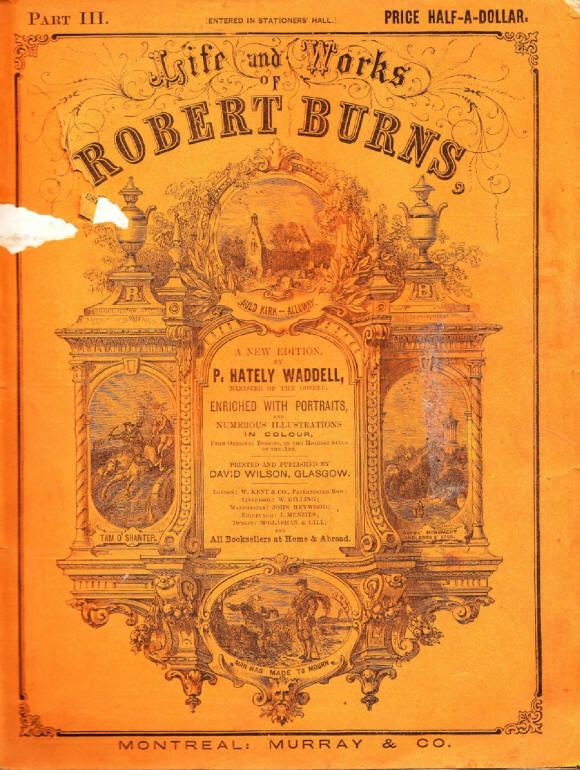

Cover of Part III of Waddell’s Life and

Works, Canadian issue (Montreal, [?1867])

Each 32-page part cost one shilling (more

for part 25, which was double the normal length), and each had a

full-page illustration, initially chromolithographs but later less

garish steel engravings. The parts did not consist of consecutive pages,

but each month offered groups of pages from different parts of the work.

It is also clear that, while the text itself was very carefully

prepared, Waddell improvised and added to his original plan, in the 110

page appendix, as correspondents wrote in with new biographical material

and anecdotes (cf. Scott, “The mysterious W.R.”). Robert Betteridge and

I have recently been disentangling this complicated story, which is too

complex to discuss fully here (but see Scott and Betteridge,

forthcoming). Waddell’s edition was widely advertised and enormously

successful, with a reported print-run of 20,000 copies a month.

Moreover, almost as soon as the part-issue was completed, the publisher

not only started selling the work in volume format, but started a second

two-year cycle of part-publication (1870-1872), this time with 26 parts

and with the pages in straightforward sequence. Earlier this year, I

chanced on a single issue from a hitherto-unrecorded Canadian part-issue

of the Waddell edition. Yet, as far as we can tell, of what must have

been hundreds of thousands of individual Waddell parts, only one set is

now recorded as surviving in original condition, in the National Library

of Scotland. The Roy Collection set, for instance, has been rebound, but

with the wrappers preserved, bound in at the back of the volume. Both

the NLS and Roy Collection copies also have a number of inserts or

advertising flyers drawing attention to special discoveries in that

month’s number.

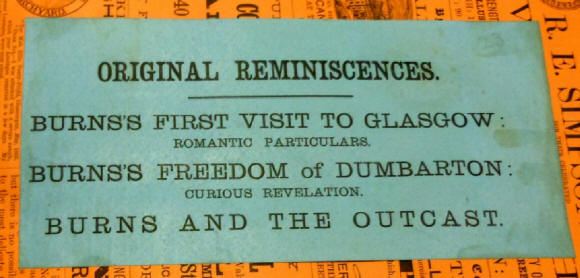

Advertising insert from Waddell’s Life and

Works, Part XXIII (February 1869) The

Gilfillan edition, the National Burns, used a very similar format and

marketing model to Waddell, but a much more straightforward arrangement, and no

signs of last-minute improvisation. The publisher, William Mackenzie of Glasgow,

had already issued one edition of The Complete Works of Burns in

1870-1871, in 17 parts, each of 32 pages with two engravings, at one shilling a

part; for that edition, the size and format was almost exactly the format that

Dickens had made famous for publishing his novels. Surprisingly, Mackenzie’s

1870-71 edition does not seem to be listed by Gibson or Egerer (but cf. Sudduth,

p. 126). To retain subscribers during the year and a half of publication,

Mackenzie had developed a shrewd marketing gimmick, promising that the last

seven parts would each have a small ticket printed on the back cover, and that

subscribers who mailed in the seven tickets would “receive for framing a Copy of

the Magnificent Portrait of Burns, after … Nasmyth,” which would be mailed

“carefully packed on a roller,” for which they had to pay another sixpence. At

least some purchasers took the bait, for the set in the Roy Collection has these

tickets duly snipped out.

The

editor, too, had been involved with a earlier Burns project. The Rev. Dr. George

Gilfillan (1813-1878), a Free Kirk minister and well-known literary critic, had

edited Burns in 1856 for a different publisher. For this new project, he

completed a new full-scale life, though he died before the edition began to

appear. The Gilfillan/Mackenzie National Burns gets only the briefest of

entries in Egerer, and Gibson in 1881 actually provided fuller information (Egerer,

799, p. 255; Gibson, p. 97). In book form, the title-pages of the two volumes

were dated 1879 and 1880, but it was issued first in fifteen parts, at two

shillings a part, and also in quarterly divisions at ten shillings and sixpence.

It was fully illustrated, with portraits of Burns and Jean Armour (and Gilfillan

himself), engravings of Burns’s homes, illustrations to the poems (mostly

engravings in the text, rather than printed separately), music or at least the

airs to the songs, a facsimile of Burns’s handwriting, and a picture of the

Burns Monument at Alloway.

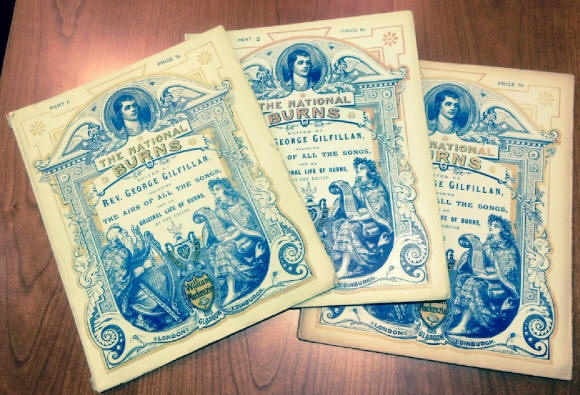

Wrappered parts from George Gilfillan’s The

National Burns (1879-1880)

Given the number of competing editions then

available, the challenge for Mackenzie was not just to publish, but to

market and sell, his new collected Burns. Once again, subscribers who

stayed the course were entitled to a “Life-Size Portrait of BURNS,” this

time after the drawing by Skirving. The Roy Collection has a related

item that casts light on his marketing efforts. This was a specimen or

“salesman’s dummy” that contained samples of a part-issue cover, and

sample pages, together with a sample of the gilt-stamped cover for the

edition in volume form. Such samples, much lighter to carry than the

books themselves, were often used by publishers’ sales representatives

when visiting bookshops in other towns or cities, but they were also

convenient for agents going door-to-door trying to sign up subscribers.

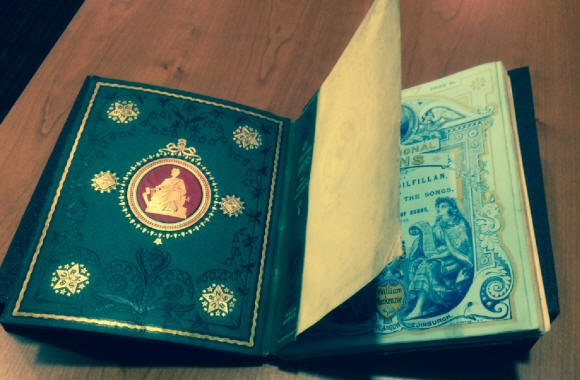

Salesman’s dummy for Gilfillan’s National

Burns, showing wrappers for the part issue and gilt-stamped cloth for

the volume binding.

A few years ago, Bill Dawson gave the Roy

Collection a rather similar salesman’s dummy for the Henley-Henderson

Centenary Burns. However, this was put together only after the edition

had been completed. It includes extracts from reviews as well as sample

contents and binding, but it does not offer the option of subscribing to

a part-issue.

The last major new Burns edition to be issued in parts seems to have

been William Wallace’s full-scale revision of the earlier Chambers

edition, which was published in book form in four volumes in 1896, with

several subsequent reprintings. I was in fact surprised to find that

Chambers-Wallace, unlike its chief late Victorian rivals, the Scott

Douglas and Henley-Henderson editions, was available in 22 blue-wrappered

parts, each of 96 pages, published at two weekly intervals, at a cost of

one shilling a part. This differs from earlier examples of part-issue,

in that the parts were not released in advance of publication in book

form; they are a straight printing from the same sterotype plates as the

volumes, though with narrower page margins. Because the editing and

typesetting was all complete before part 1 hit the bookstalls, not still

a work-in-progress, it could be issued with a part every two weeks,

rather than monthly or at irregular intervals. It is worth noting that

the title-page for the first volume occurs at the beginning of part 1,

rather than the title-pages and prelims coming at the end of the final

number, just in time for rebinding, as was more usual for part

publication. Moreover, while the book form was available in a special

limited large-paper version, the part-issue was clearly a much more

humdrum production, so much so that it goes unmentioned in Egerer (cf.

Egerer 893, p. 271 ff.). It did, however, include the same illustrations

as the more formal version.

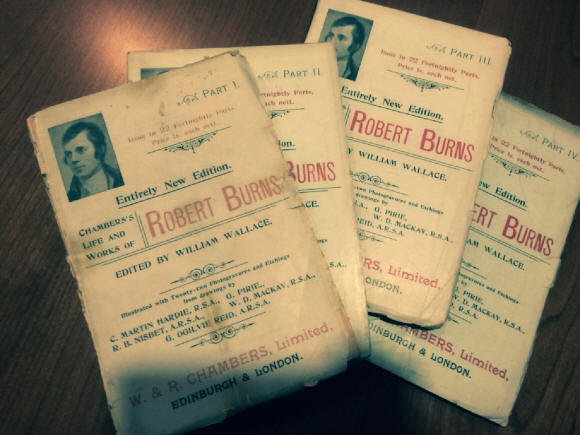

The Chambers-Wallace Life and Works of

Robert Burns (1896), in parts

The Chambers-Wallace part-issue also,

however, highlights the way serial publication might increase the

pleasure of reading a new Burns edition, by its format, not just through

commentary or illustrations. By the 1890s, the sheer amount of material

by and about Burns that was available to editors had grown inexorably.

Sitting down to read one’s way through the four fat volumes of

Chambers-Wallace, with the six volumes of Scott Douglas already looming

on the shelves, and a dim consciousness that Henley and Henderson’s

small-print textual notes if studied closely contained much new

information, would seem burdensome. The big late Victorian editions are

imposing on the shelf, eloquent symbols both of a commitment to the

Bard, and of one’s own income and respectability, but more Burnsians,

then and now, will have bought them, maybe dipped into them and set them

aside, or looked something up, than ever read them cover to cover to

cover. By contrast, with its convenient 5 x 8 ¼ inch magazine-like

format, one can imagine commuters snapping up each new slim installment

from the station bookstall on publication day to read on their journey

home, with the promise of more, but not too much more, to read over the

weekend. At least in format, Chambers-Wallace in parts was competing,

not with the illustrated family bibles of the 1860s, but with the latest

Conan Doyle in the Strand magazine.

Part-publication, then, represents an important aspect of the

nineteenth-century Burnsian experience. It is not surprising that an

antiquarian bookdealer would not have encountered them. The set my

longtime friend described in his email, a late example published just

before the First World War, represents the staying power of this

publishing mode well after its heyday. Though few libraries now preserve

even sample parts, publication in that format was in fact widespread.

I’d be happy to hear from any collectors fortunate enough to own further

examples.

References

W. G. Blackie, Sketch of the Origin and Progress of the Firm of Blackie

& Son, Publishers, Glasgow, from its Foundation in 1809 to the Decease

of its Founder in 1874 ([Glasgow]: printed for private circulation,

[1897]).

Bill Dawson, “The First Publication of Burns’s ‘Tam o’ Shanter’,”

Studies in Scottish Literature, 40 (2014): 105-115: and in Burns

Chronicle for 2016, 125 (November 2015), 15-25.

J. W. Egerer, A Bibliography of Robert Burns (Edinburgh: Oliver and

Boyd, 1964)

Joe Fisher et al., Catalogue of the Robert Burns Collection, The

Mitchell Library, Glasgow (Glasgow: Glasgow City Libraries and Archives,

1996).

[J. Gibson], The Bibliography of Burns (Kilmarnock: James M’Kie, 1881).

G. Ross Roy, and Patrick Scott, “A Conversation with G. Ross Roy,” Burns

Chronicle Homecoming 2009, ed. Peter J. Westwood (Dumfries: Burns

Federation, 2010), 414-424.

Patrick Scott, “The Mysterious ‘W.R.’ in the First Commonplace Book,”

Burns Chronicle for 2016, 125 (November 2015), 8-14.

__________ and Robert L. Betteridge, “The Part Issue of Hately Waddell’s

Life and Works of Robert Burns,” forthcoming.

Elizabeth Sudduth, The G. Ross Roy Collection of Robert Burns, An

Illustrated Catalogue (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press,

2009).

Christopher Whatley, Immortal Memory: Burns and the Scottish People.

(Edinburgh: John Donald, 2016). |