|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

What an honor to have Clark McGinn send the following article. Clark is a

gifted Scottish speaker, talented writer, consummate Burnsian, and a

Historian in his own right. He would easily be described as “a Burns

scholar”. I’ve never seen anyone credit his sources like Clark, who knows as

much about the Bard as anyone I know!

Clark McGinn is a man of the people because he speaks and writes from his

heart. Those who are fortunate to hear him speak or read his books and

articles understand him. We are fortunate to have him again in this space

and I in particular find this topic illuminating. Sir Walter Scott occupies

a prominent spot in my library as well as in my heart. Scott was my first

Scottish hero, long before Burns became such an important part of my life.

No man loved Scotland and her people more than Scott, including Burns. While

Scott seemed to have been the forgotten writer during the big Homecoming

events last year, he stands tall in my life. He was the world’s first

celebrity writer! It is because of him that today we have “historical

novels”.

Thanks, Clark, for dropping by again. You are always welcome and I’d like to

pay tribute to the Burns Chronicle where this article previously appeared.

(FRS: 8.19.20)

THE TEARS OF ROBERT BURNS

By Clark McGinn

Immediate Past President, The Burns Club of London

A

question I have often asked myself was ‘why did Robert Burns cry the day he

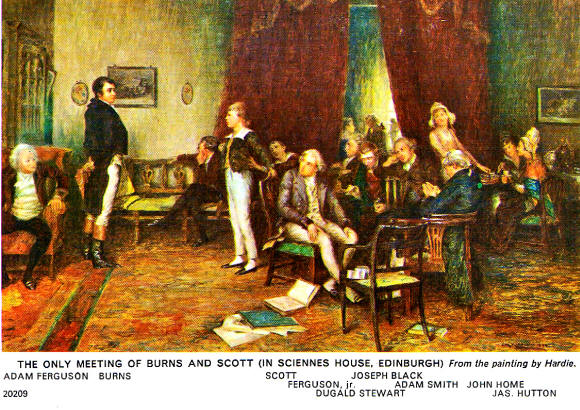

met young Walter Scott?’ You will remember the scene as drawn by Sir Walter:

‘As for Burns, I may truly say, Virigilium vidi tantumi.

I was a lad of fifteen in 1786-7, when he came first to Edinburgh, but had

sense and feeling enough to be much interested in his poetry, and would have

given the world to know him; … I saw him one day at the late venerable

Professor Ferguson's, where there were several gentlemen of literary

reputation, among whom I remember the celebrated Mr Dugald Stewart. Of

course we youngsters sate silent, looked and listened. The only thing I

remember which was remarkable in Burns' manner, was the effect produced upon

him by a print of Bunbury’sii,

representing a soldier lying dead in the snow, his dog sitting in misery on

the one side, on the other his widow with a child in her arms. These lines

were written beneath, -

Cold on Canadian hills, or Minden’s plain,

Perhaps that parent wept her soldier slain:

Bent o'er her babe, her eye dissolved in dew,

The big drops, mingling with the milk he drew,

Gave the sad presage of his future years,

The child of misery baptized in tears.

Burns seemed much affected by the print, or rather the

ideas which it suggested to his mind. He actually shed tears. He asked

whose the lines were, and it chanced that nobody but myself remembered

that they occur in a half-forgotten poem of Langhorne's, called by the

uncompromising title of 'The Justice Of The Peace'iii.

I whispered my information to a friend present, who mentioned it to

Burns, who rewarded me with a look and a word, which, though of mere

civility, I then received and still recollect, with very great

pleasure.’

This is the famous literary collision, described in Sir

Walter’s letter of 10th April 1827 which was quoted in Lockhart’s Life of

Burnsiv.

There is corroborating detail from the reminiscences of Ferguson’s son Adam

(latterly Sir Adam) who was also there that day. Sir Adam was a friend of

the Chambers brothers, to whom he bequeathed his father’s Bunbury print at

his own death in 1854. At the Centenery Burns Supper of the Caledonian

Society of London in 1859, William Chambers reported his late friend’s

remembrance of that day Burns and Scott met:

‘It seems that Burns did not at first feel

inclined to mingle easily in the company. He went about the room looking

at the pictures on the walls. At length a picture arrests his attention;

it is a common-looking print, in a black frame. The painter of the

picture is Bunbury, [Here Chalmers describes the print and the verse and

shows the actual picture to the assembled Caledonians as if it were a

holy icon]…

Burns was much affected by the print; he read the lines,

but before getting to the end of them, his voice faltered, and his big

black eye filled with tears.

v

What happened here to draw the poet’s tears? What conclusions can we draw

from the two brief descriptions of that afternoon?

The party was held in early1787 (the exact date is uncertain)

at Professor Adam Ferguson’s home in Sciennes in Edinburgh and we can see

from the recollections of the participants that Burns’s attention was caught

by a print of a woman keening over her dead soldier husband while nursing

their infant child. Underneath this sentimental picture was the saccharine

verse quoted above but which was unattributed until young Walter identified

it as being from Langhorne’s poem The Country Justice which has the

consequential effects of, and suffering caused by, war as one of its themes.

And there's the secret to the Bard's tears. The poem celebrates the

engagement at Quebec where the Highlanders under General Wolfe stormed the

French out of Canada at the Heights of Abrahamvi

(13th September 1759) and similarly in Europe the battle of Minden (1st

August 1759) where Scots infantry participated in one of the most amazing

feats of arms: footsoldiers routing the crack French cavalry in a rose

garden. These crucial victories set the foundation of the British Empire –

but to us of course 1759 is more important for being the year of Robert's

birth.

We cannot know for certain what Burns was thinking of, but it’s not a great

leap of faith to imagine him thinking that had his father ‘gaun tae be a

sodger’ and died as one of the many Scots who fell in the line of duty in

1759, Robert could have been the babe in arms at the centre of Bunbury’s

painting and Langhorne’s verse. The memory of his father’s death in February

1784 could only have made the coincidence more poignant particularly if this

meeting happened in early 1787. The connexion between his birth date and the

anniversary of his father’s death brought the poet to tears.

It's characteristic of Burns's sympathy and sense that for a moment in a

grand Edinburgh salon he was transported back to tears.

i

Trans: ‘I only saw Virgil; I was not intimate with the great man.’ from

Ovid ‘De Tristibus’.

ii

Henry William Bunbury (1750 – 1811) ‘Affliction’ (1783) which influenced

the more important painting by Joseph Wright of Derby ‘The Dead Soldier’

(1789) based on the same quotation.

iii

Actually ‘The Country Justice’ by John Langhorne (1735 – 79). In future

years Scott would use Langhorne’s verse as epigraphs – see Rob Roy c XIX

for example.

iv

‘Life of Robert Burns’ J.G. Lockhart, Edinburgh 1828 (Reprint London

1976) pp 81-2.

v

‘Chronicle of the Hundredth Birthday of Robert Burns’ ed. James

Ballantine, Edinburgh 1859 p427

vi

Also alluded to in the Jolly Beggars – Air ‘I am a son of Mars’ ll 6,7

‘My prenticeship I past, when my leader breathed his last. When the

bloody die was cast on the heights of Abram:’

|