|

THE Netherlands were, in the latter part

of the seventeenth century, the chief rival of this country in

colonizing enterprise and naval power. Since the days of Charles I.

they had afforded an asylum to discontented and disinherited persons

from England and Scotland alike. [Coltness Collections. Chambers's

Domestic Annals, ii. 540.] Charles II. himself had found a retreat

there while he waited an opportunity to recover the double crown

from the Government of Oliver Cromwell. The Netherlands also were

the arsenal from which the weapons were obtained which were used

against the Government troops at the battles of Rullion Green,

Drumclog, Bothwell Bridge, and Ayr's Moss. Accordingly, the arms and

men were both ready there when the accession of Charles II.'s

brother, the Duke of York and Albany, as King James VII. and II.,

seemed to offer a favourable opportunity for another attempt. The

new king was a Roman Catholic, and for that reason unpopular, and

the discontented elements at Amsterdam and the Hague resolved to

seize the chance to effect a revolution without delay. Within three

months of the beginning of the new reign two strong and fully

equipped expeditions sailed from the Dutch ports.

The Earl of Argyll, as we have seen, had

pleaded lack of means as a reason for refusing to repay the money

borrowed by his father from Hutchesons' Hospital and the Town

Council of Glasgow. But lack of means did not prevent him from

fitting out a formidable expedition, with ships and men and ample

munitions of war, for a more definite attempt than had yet been made

to overthrow the Government of Scotland. And thus, while the Duke of

Buccleuch and Monmouth, son of Charles II. and Lucy Walters, with

certain pretensions to legitimacy and a claim to the throne, landed

with a force in the south-west of England, Argyll, at the head of an

equally threatening array, disembarked in leis own country, near the

disaffected southwestern district of Scotland. The story of that

ill-starred campaign is told with fullness and, for him, unusual

fairness by Lord Macaulay in his history of that time.

Had the Earl been a leader of

military ability, like the two Leslies or Montrose, he might easily

have raised an army of formidable size and determined character from

among the Covenanters of Renfrewshire, Ayrshire, and Galloway, and

might have opened another campaign like that of forty years earlier

which resulted in the overthrow and execution of Charles I. The very

real apprehensions of the Government as to such a possibility are

shown by the fact that, at the news of Argyll's rebellion, some two

hundred Covenanter prisoners then in Edinburgh were sent to safer

keeping in the strong northern fortress of Dunnottar. [Wodrow, iii.

322.]

But Argyll was no general. Leaving

his munitions, with a small garrison, on one of the islands at the

mouth of Loch Ridden in the Kyles of Bute, he proceeded, with a

force of some eighteen hundred men, to cross Loch Long and march

upon Glasgow. After fording the Water of Leven at Balloch, however,

the rebels came in sight of a strong body of Government troops

posted in the village of Kilmaronock. Argyll was for giving instant

battle, but the expedition was really under the control of a

committee of which Sir Patrick Hume of Marchmont was the leading

spirit, and on his advice it was determined to delay till night, and

then, crossing the Kilpatrick Hills, give the redcoats the slip, and

endeavour to reach the objective at Glasgow, where, it was expected,

strong reinforcements would join the rising. But the night was dark,

the guides mistook the track, and among the bogs and in the darkness

many of the Highlanders took the opportunity of going home. In the

morning at Kilpatrick the Earl found his force reduced to five

hundred men. Perceiving further attempt to be hopeless, he disbanded

his company, and, crossing the Clyde, changed clothes with a

peasant. He had made his way as far as Inchinnan, when his

appearance excited suspicion, and he was seized by some rustics. He

is said to have betrayed himself by the exclamation "Unhappy

Argyll!" and as a result found himself under strong guard that night

in the tolbooth of Glasgow. Thence, almost immediately, he was

conveyed to Edinburgh, where, on the warrant of a bygone sentence,

he was executed on 30th June.

How Argyll expected to find support

or reinforcements in Glasgow is difficult to understand. It is true

that while he, with three other officers and "ane poor Dutchman,"

"being all wounded," lay in the tolbooth, the magistrates expended

the sum of £55 2s. Scots on dressing their wounds and furnishing

them with drugs. [Burgh Records, 10th Aug. 1685.] But that was no

more than a matter of common humanity. On the accession of King

James the magistrates had sent the new monarch a most loyal address.

[Ibid. 13th March.] At the news of Argyll's sailing past the

Orkneys, three regiments of Lothian and Angus militia had been

quartered in the town, and the city fathers had themselves equipped

a body of eleven militiamen who were on service for forty-four days.

[Ibid. 10th Aug.]

Argyll's invasion was the last armed

attempt of any size made against the Government by the Covenanters

in the West of Scotland. Lord Macaulay has justly said of it, what

might be said of the earlier efforts of the Covenanters at Dunbar

and Bothwell Bridge, "What army commanded by a debating club ever

escaped discomfiture and disgrace?" Nevertheless the alarm which it

caused was not the less profound. The Privy Council protested

against the withdrawal of troops to meet Monmouth's invasion in the

south, declaring that not many of the rebels had been captured, and

that there remained "a vast number of fanaticks ready for all

mischief upon the first occasion." [Reg. Priv. Coun., 3rd Series,

vol. xi.]

At the end of July, a month after

Argyll's rebellion had been suppressed, the prisoners, eight score

and seven in number, who at the outbreak of hostilities had been

sent for safe keeping to Dunnottar, were brought south again, and

tried by the Lord President of the Court of Session and four earls

at Leith. Among those who took the oath of allegiance and were set

free were two Glasgow men, John Marshall and David Fergusson; but

the greater number, remaining refractory, were sent to the

plantations. [Woodrow, iii. 326.]

It is instructive here to note that,

while so many of the Covenanters were being shipped out of the

country, the Government did not object to another much greater body

of Dissenters coming in. The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by

the Government of Louis XIV. is said to have brought some fifty

thousand French Protestant refugees into this country. A colony of

these settled in Edinburgh, where a large building, known as Little

Picardy, was erected for their accommodation, and where they

established a cambric factory. [Maitland's History of Edinburgh, p.

215. The spot is commemorated in the name of Picardy Place.] And no

doubt some of them, like the Huguenot refugees from the Massacre of

St. Bartholomew a hundred years before, made their way to Glasgow

and the West, to help the prosperity of the country by their skill

and industry. [Names like Verel and Pettigrew (Petit croix ?), to be

found in the Glasgow Directory to-day, probably date from one of

these immigrations.] In particular the paper-making industry in

Glasgow was started by one of these refugees. Coming to Scotland

with his little daughter after the Revocation of the Edict, Nicholas

Desham made a living for a time by picking up rags in the Glasgow

streets, and in time saved enough i o start a paper mill close by

the old bridge of Cathcart, where the work continued to be carried

on till near the end of the nineteenth century.

The rebellions of Argyll and Monmouth

could not but give the last spear-prick to the exasperation of King

James. In the proclamations of each of these leaders—probably both

drawn up by "Fergusson the Plotter"—he had even been accused of

poisoning his brother, the late king. It was too much to expect that

the Government should not take the strongest measures to punish and

prevent a repetition of such dangerous treasons. Accordingly, while

Judge Jeffries was sent down to visit with retribution the

supporters of Monmouth in the south-west of England, measures were

redoubled to stamp out the embers of rebellion in the south-west of

the northern kingdom. In the one case the result was the "bloody

assizes" of the notorious English judge, and in the other the

"killing times" which have left so dark a stain in the Scottish

annals. The Covenanters in their day of power had been not less

ruthless, and they were to be equally ruthless again; [In their

treatment of prisoners after the defeat of Montrose at Philiphaugh,

for instance, and in the "rabbling out" of the episcopal clergy and

their families after the Revolution. Two hundred of these episcopal

clergy were rabbled out in the south-west of Scotland alone.] but

two blacks do not make a white, and the fines and torturings and

military executions of those "killing times" make one of the most

distressing chapters in the history of the country.

The King himself, though so far away

as Whitehall, took a much more direct and intimate part in the

actual government of Scotland than might be believed in the

twentieth century. Of this an illuminating illustration is afforded

by an episode in which two of the provosts of Glasgow were

concerned.

In October 1682 John Barnes was

nominated by Archbishop Ross to fill the provostship, and he was

appointed again in 1684. Barnes appears to have been a man of rude

energy and determination, for he proceeded to fill up certain

vacancies in the Town Council on his own initiative, without the

usual process of nomination by the existing members; and, in spite

of protest by the previous provost, John Bell, he made good the

appointments, and had one of his nominees, who was not even a

burgess, appointed a magistrate by the Archbishop. Also, towards the

end of his term of office in September 1684, the Town Council was

called upon to pay £6 9s. sterling to one Allan Glen for a horse he

had newly bought that died at Edinburgh, "being bursten ryding

thither be the provost." By that time Barnes appears to have been in

financial difficulties, and, as Archbishop Ross had been translated

to St. Andrews to fill the place of Archbishop Burnet, who died on

24th August, he apparently resolved to play the part of the

unfaithful steward, and make the most of his opportunities before

being superseded in the provost-ship. The Town Council minutes of

26th September record a spate of payments. The keeper of the

tolbooth clock and chimes had his salary raised from £5 to £10

sterling. A contract, at what looks a very high price, was given to

Robert Boyd for building a wall to protect the new washing-green on

the north side of the Cathedral and a bridge beyond the Cowcaddens.

John Waddrop, a tanner, was forgiven a debt of 950 merks in

consideration of a number of hides that had been taken from his

tanning pits to protect houses from a recent fire in Gallowgate.

£100 Scots was given to Robert Stirling in consideration of loss he

had sustained in carrying on the Sub-Dean's mill. John Cumming

received £10 sterling on the plea that his tack of the Green had

proved unprofitable through few graziers pasturing their cattle

there. £725 10s. was paid to Bailie Anderson for plenishing and coal

and candle supplied for "the general's" lodging. In view of the

agreement that the librarian at the University should be appointed

every four years alternately by 'the college authorities and the

Town Council, Mr. James Young, Professor of Humanity, who within a

year had received the appointment from the college, was granted the

post for the next term of four years, three years in advance. The

town clerk, George Anderson, in addition to his expenses for various

errands on the town's business, was given a douceur of £480 for his

pains, while three clerks in his office received £18o of a gratuity

for their "extraordinar pains." Bailie Graham was paid £223 Scots,

of which £40 were for expenses in attending Archbishop Burnet's

funeral, and the rest "for drink spent in his hous be the

magistratis wpon the touns accompt since the twenty eight of June

last." And William Stirling, bailie depute of the regality, and John

Johns, procurator fiscal of the commissariat of the city, received

£25 sterling, for their pains and service and "their discretioun to

the toun and inhabitantis." Most glaring of all, a new tack of the

teinds of the Barony was arranged with Archbishop Ross, entailing a

greatly increased sum to be paid by the city to the prelate, while

the deed previously signed by Ross was ordered to be delivered up to

him. As there was no time to lose over this transaction, John McCuir,

writer, was sent post haste through the country to secure the

signatures of the dean and chapter to this document. Finally,

Provost Barnes himself had apparently been borrowing considerable

sums from the city funds. His debt amounted to £1706 12s. 6d. This

sum the magistrates and Council very complaisantly agreed to make

over to him as a gift, "taking in their consideration the great

pains and trowble the provest hes bein at in ryding and doing the

touns affairis these twa yeiris." At the same time, probably to make

the transaction appear less extraordinary, John Wallace, the

deacon-convener, was forgiven a similar debt of £80, "for his pains

and ryding in the touns affairis." [Burgh Records, 26th, 27th, and

29th Sept. 1684.]

Two days after the last of these

transactions another provost, John Johnstone of Clathrie, was

appointed, and within a month the new Town Council proceeded to deal

actively with these abuses.

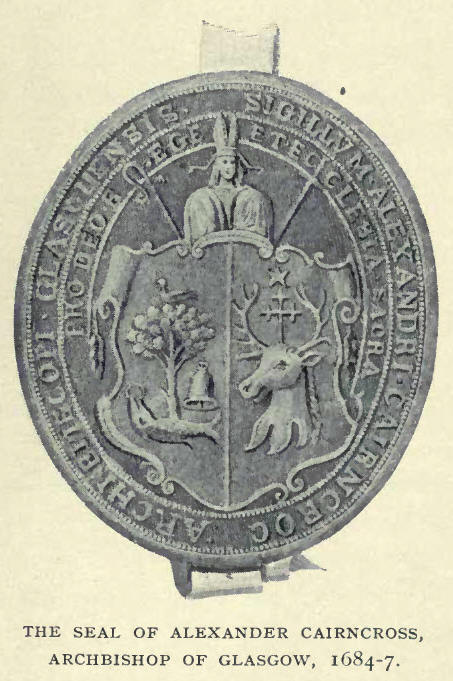

Provost Johnstone was a man of

substance, the laird of considerable estates in Nithsdale, and one

of the "venturers" who fitted out the Glasgow privateer George for

action in the war with the Dutch of that time. It was no doubt

through his Dumfriesshire connection that he was known to the new

Archbishop, Alexander Cairncross, who had been minister of Dumfries

before being appointed, through the influence of the Duke of

Queensberry, first to the Bishopric of Brechin, and, later in the

same year, to the Archbishopric of Glasgow. All these three

Dumfriesshire men, the Duke, the Archbishop, and the Provost, were

to be visited presently with the royal displeasure for their lack of

complaisance in the arbitrary actions of King James.

Meanwhile the Provost lost no time in

showing that he had a mind of his own. On 27th October the Town

Council, in view of the heavy load of debt with which the city was

burdened, resolved to appoint no regular physician for the poor,

stopped the payment of money to pensioners, and resolved that the

magistrates should be empowered to give no more than half a dollar

at a time to any poor person. It also considered certain abuses of

power perpetrated by the late magistrates, who had given judgment in

actions for debt and had exacted fines without proper trial and

sentence in court, and it ordered that no magistrate should

determine anything between the town's people above the value of

forty shillings Scots, without proof and sentence in a proper court.

Next, on 4th November the Council dealt with the gift of £1706 12s.

6d. that had been made to Provost Barnes, declared it to be

exorbitant and without precedent, and instructed the town's

treasurer to pursue Barnes for payment of the amount of his bond.

[The action was decided against Barnes by the Court of Session on

3rd March.—Morrison's Dictionary of Decisions, p. 2515.]

Provost Johnstone, further, went to

Edinburgh and con- sulted Sir George Lockhart and the other legal

advisers of the town with regard to the other gratuitous payments

made by the late magistrates and Council—payments which were bluntly

termed embezzlement. Last and most important of the matters

regarding which this high legal advice was taken was the new bond

granted to Archbishop Ross for 20,000 merks for the tack of the

Barony teinds. By the advice of Sir George Lockhart and the other

lawyers, and with the approval of the Town Council, an action was

raised for the reduction of this tack, the plea being that 20,000

merks was an exorbitant grassum for a tack of teinds not worth 500

merks a year, and it was averred that the tack had been negotiated

by Barnes "for his own ends when he was put in by the archbishop to

be provost, and when he was bankrupt."

In this action Johnstone appears to

have made some statements against Archbishop Ross which gave offence

to that prelate. The latter complained to King James, who took the

statements as an insult to the established order, and by a letter

dated Whitehall, 19th March, 1686, directed the Privy Council to

take action in the matter. [Fountainhall's Decisions, 17th June,

1686.] In consequence Johnstone was arrested, tried by a committee

of the Privy Council with witnesses, and found guilty "of being

accessory to the giving in of a defamatory bill of suspension to the

Lords of Session against the Lord Archbishop of St. Andrews, and of

uttering calumnious and injurious expressions at several times

against His Grace in relation to the said bill." Therefore, in

pursuance of a letter from the King, the Privy Council turned him

out of the magistracy, ordered him on his knees at the bar to crave

pardon of the Archbishop, committed him to the tolbooth, and

directed that, after liberation, he should repair to Glasgow and

acknowledge his crime to the Archbishop. At the same time he was

mulcted in the expenses of the action, including £7 sterling to the

Lords Secretaries on account of the letters sent down by the King.

[Reg. Priv. Coun. 25th June, 1686.] Next day, in obedience to an

order from the Privy Council, and the necessary letter from

Archbishop Cairncross, the Glasgow Town Council turned Johnstone out

of the provost-ship and reinstalled John Barnes to act as provost

till the next election. [Burgh Records of date.]

The imprisonment of the unlucky

provost did not last long. On 30th June, on the plea that his health

was suffering in prison, and upon the intercession of Archbishop

Ross himself, he was set free, and ordered to compear before the

magistrates and Town Council of Glasgow before 10th July, and crave

pardon in terms of the decreet, under a penalty of a thousand merks

in case of failure. [The proceedings against Johnstone are detailed

in a paper read by Mr. Andrew Roberts before Glasgow Archeological

Society, 16th Jan. 1890 (Transactions, new series, ii. 34-43).]

Accordingly, on 5th July, Johnstone duly attended before the city

fathers, and did "crave pardon for his cryme and injurie done to his

Grace the Archbishop of St. Andrews." Obviously the Town Council had

dramatic moments among its experiences.

The arbitrary action of King James in

thus displacing Provost Johnstone, and installing an individual more

complaisant to his purposes, was not the last high-handed exercise

of the royal authority which Glasgow was to experience. On the eve

of a new election of magistrates in that year, James sent a letter

to the Scottish Council ordering the suspension of all elections in

royal burghs till his further pleasure should be known, and

directing the existing councils to continue meanwhile in the

exercise of their authority. Two months later another royal letter

came down to the Privy Council, directly nominating not only the

provost, magistrates, and town council for the coming year, but also

the dean of guild, deacon-convener, and deacons and visitors of each

of the trades, "being such whom his Majesty judges most loyall and

ready to promote his service." By this means Barnes was directly

appointed to another term of office. [Burgh Records, 25th Sept. and

18th Nov. 1686.]

Archbishop Cairncross was directed to

attend at the tolbooth and see that these instructions were duly

carried out. Such an instruction was itself an infringement of the

rights and authority of the archbishopric which could hardly fail to

rankle in the mind of the prelate. Arbitrary royal acts of this

kind, which were rapidly alienating the general loyalty of the

country, were to exhibit one of their first sinister results in the

case of the Glasgow archbishop. Along with his patron, the Duke of

Queensberry, Cairncross ventured to express disapproval of certain

of the decrees issued by James on the royal authority alone, without

consent of parliament, and was forthwith deprived of his

archbishopric. At the same time the Duke was deprived of his offices

as Lord Justice-General and Lord High Treasurer of Scotland.

The mandates of which Queensberry and

the Archbishop disapproved were those by which James sought to show

favour to members of his own communion, the Church of Rome. In order

to do this with a show of fairness, James had to include in his

indulgences the people hitherto denounced as conventiclers. By the

most notable of these proclamations he "suspended all penal and

sanguinary laws made against any for nonconformity to the religion

established by law in this our ancient kingdom," and allowed all men

"to meet and serve God after their own way and manner, be it in

private houses, chapels, or places purposely hired or built for that

use." [Wodrow, iv. 226-227.] This royal act, in which they found

themselves indulged along with Roman Catholics .and Quakers, greatly

incensed the Covenanters, who had no wish to see toleration for any

form of worship but their own. Yet it had certain solid results in

Glasgow. Upon its permission the presbyterians in Glasgow proceeded

to build two great public meeting-houses, one at Merkdailly on the

south side of Gallowgate, which ceased to be used in 1690, the other

between the New Wynd and Mains Wynd, south of Trongate, which was

rebuilt as the Wynd Church about 1760. [McUre's Hist. ed. 1830, pp.

6o, 6i. Burgh Records, 28th Sept. 1687, note. At the Reformation,

when Glasgow had a population of little over 4000, the city had one

church, the Cathedral, with one minister. In 1687 a second minister

was appointed as a colleague. Next the old church of St. Mary and

St. Anne, now the Tron Church, was restored, and a third minister

was appointed in 1592. Three years later a fourth minister was

appointed and in 1599 took charge of the landward part of the

parish, then separated from the city part, and named the Barony

Parish. Its congregation worshipped in the Lower Church of the

Cathedral. In 1622, further accommodation being required, the old

church of the Blackfriars monastery in High Street was repaired, to

become known as the Blackfriars or College Church. In 1648 another

congregation was installed in the Cathedral, and became known as the

"Outer High," as it worshipped in the nave. This, after removal in

1836, became St. Paul's, as the Wynd Church, founded in 1687, became

St. George's. Of the city's later churches, St. David's (the

Ramshorn) dates from 1720, St. Andrews from 1740, St. Enoch's from

1780, St. John's from 1817, and St. James's, purchased from the

Methodists in 1820.]

Meanwhile the town, in addition to

its own considerable debt, found itself called upon to raise z2oo

sterling per annum as a tax payable to the King, with other dues and

charges which brought the amount up to £1600 sterling, a very large

sum, in the value of money at that time, to be raised by a small

community. The stent-masters were therefore sent round to collect a

tax, and the order was given to sell by auction the houses and

warehouses belonging to the city at "Newport, Glasgow," as well as

the stores and houses which had been bought by the town from the

defunct Fishing Society. [Burgh Records, 20th Jan. 1687. The town

had had great trouble in taking over the assets of the old Fishing

Company—the ill-judged State enterprise initiated by Charles I. (see

supra, page 206). See Burgh Records, 1683, pp. 327, 331, 343, 344,

346.] To help the town's finances the King granted a right to the

magistrates to levy excise duties upon ale and wine—four pennies

Scots upon every pint of ale, two merks upon every boll of malt,

twenty shillings on every barrel of mum beer, fifty pounds on every

tun of French, Spanish, or Rhenish wine, and fifty pounds on every

butt of brandy, aquavito, or strong waters, sold or consumed within

the city. Rapture at the royal grant seems to have gone to the heads

of the city fathers, as the liquor itself might have done, and they

wrote a letter of thanks to the King in probably the most abject

terms ever employed by a Scottish Town Council. This precious

epistle began: " May it please your most sacreed Majestie,—In the

deepest sense of gratitude, wee most humblie prostrat ourselves at

your royall feet, acknowledgeing your Majesties clemencie and

bountie towards this your city of Glasgow in rescuing it from

sinking under inevitable ruine." Further on it proceeds, " For our

pairt, who by your Majesties nomination represent your authoritie

here, wee shall, under the prudent conduct and unspotted loyall

example of the most reverend archbishop your Majestie hath bein

graciouslie pleased now to nominat for ws, witness to the world our

fervent zeal against all your adversaries," etc. [Burgh Records,

28th Feb. 1687. The archbishop mentioned was Cairn-cross' successor,

John Paterson, previously Bishop of Edinburgh, who owed his

promotion to the ardour with which he served the wishes of the Court

and his endeavours to move Parliament to meet the King's desires for

removal of the laws against Catholics. Book of Glasgow Cathedral,

197.] By such a letter Provost Barnes no doubt felt that he had

fairly earned the King's favour, which again continued him in the

post of chief magistrate when the time for election once more came

round in 1687.

Troubles were now, however,

thickening round the head of James himself. The birth of a royal

prince on 16th June, 1688, was celebrated at Glasgow with every

demonstration of loyalty. Seven barrels of gunpowder and a large

supply of French wine were expended in rejoicings for the arrival of

that "Prince of Scotland and Waillis." [Ibid. 3rd Aug. 1688.] The

prince's birth, nevertheless, rather increased than diminished the

public discontent, for it promised a perpetuation of the Catholic

menace with which the country was threatened by the religion and

policy of King James, and which, it had been hoped, would come to an

end if the King's elder daughter Mary, wife of the Protestant Prince

of Orange, succeeded to the throne.

The rapidly growing seriousness of

the situation is reflected in events at Glasgow. Early in October,

on the rumour of serious trouble impending, the city offered to

raise ten companies of a hundred and twenty men each for the service

of the King, and the offer was promptly accepted on behalf of the

Privy Council by the chancellor, the Earl of Perth. Three days later

a complete list of officers for the companies, including the new

provost, Walter Gibson, was drawn up, and on 13th November strict

orders were issued and penalties prescribed regarding any who should

neglect their duty when called upon to mount guard in the city or

who should fail to appear "sufficientlie armed with ane sufficient

fyrelock and ane sword." [Burgh Records, 13th and 16th Oct. and 13th

Nov. 1688.]

But already, on 5th November, William

of Orange had landed at Torbay. In the days that followed, King

James had seen his armies fall away from him, his friends go over to

the invader, even his daughter Anne desert him; and on the night of

22nd December he had himself finally fled to France. The Revolution

which James had brought about by his own obstinacy and folly, had

effectively taken place. |