| OF all the districts overshadowed by the

extensive Cairngorm range the most magnificent, by universal consent, is

Rothiemurchus. It is a region entirely unique. There is nothing like it

elsewhere. If Scotland as a whole is Norway post—dated, this part of

the country is especially Norwegian. Scotland is famous for its artistic

colouring, which Millais compared to a wet Scotch pebble; but here the

colouring is richer and more varied than in any other part of the

country. The purples are like wine and not like slate, the deep

blue-greens are like a peacock’s tail in the sun, the distant glens

hold diaphanous bluish shadows, and a bloom like that of a plum is on

the lofty peaks, which changes at sunset into a velvety chocolate or the

hue of glowing copper in the heart of a furnace. A day here in October

is something to be remembered all one’s life, when the tops of the

mountains all round the horizon are pure white with the early snow, and

their slopes are adorned with the brilliant tints of faded bracken,

golden birch and brown heather, and all the low grounds are filled with

the unchangeable blue-green of the firs. At Rothiemurchus the landscape

picture is most beautifully balanced, framed on both sides by heath-clad

hills, which rise gradually to the lofty uplands of Braeriach and

Cairngorm, with the broad summit of Ben Macdhui rounding up its giant

shoulders behind the great chain itself; all coiffed with radiant cloud,

or turbaned with folded mist, or clearly revealed in the sparkling

light, bearing up with them in their aged arms the burden of earth’s

beauty for the blessing of heaven. All the views exhibit the most

harmonious relations to one another, and each is enhanced by the

loveliness of its neighbour.

Rothiemurchus is a

high-sounding name. It is a striking example of the genius which the

ancient Celtic race had for local nomenclature. It means "the wide

plain of the fir trees," and no name could be more descriptive.

Nothing but the fir tree seems to grow over all the region. It has miles

and miles of dark forest covering all the ground around, and usurping

spots that in other localities would have been cleared for cultivation.

You see almost no trace of man’s industry within the horizon. Whatever

cornfields there may be are entirely lost and hid within the folds of

this uniform clothing of fir-forest All is Nature, primitive, savage,

unredeemed. In the centre of the vast plain rises the elevated upland of

Tullochghru, about a thousand feet above the sea-level, whose farms have

a brighter green, smiling in the sunshine, contrasted with the

surrounding brown desolation. It seems to emerge like an island out of

an ocean of dark-green verdure flowing all around its base, and breaking

in billows far up the precipices of the Cairngorms. The scenery as a

whole is on such a gigantic scale that the individual features are

dwarfed. The huge mountains become elevated braes or plateaus, and miles

of mountainous fir-forest seem to contract into mere patches of

woodland. No one would suppose that the hollow which hides Loch Morlich

in the distance was other than a mere dimple in the forest, and yet it

is more than three miles in circumference, and opens up on the spot a

large area of clear space to the sky. The eye requires to get accustomed

to the vast dimensions of mountain and forest to form a true conception

of the relative proportions of any individual object. Nothing can be

more deceptive than the distances, which are always supposed to be much

shorter than they really are.

The crest of the Grants

of Rothiemurchus is a mailed hand holding a broadsword, with the motto,

"For my Duchus." Duchus is the name which they gave to their

domain. It is a Gaelic word meaning a district which is peculiarly one’s

own. Rothiemurchus was always regarded by its proprietors as standing to

them in a very special relation. Very touching expression has been given

to this sentiment in that popular work, The Memoirs of a Highland

Lady, published some few years ago. The attachment of the authoress,

who was a daughter of Sir John Peter Grant of Rothiemurchus, to her

native place was unbounded. She constantly speaks of her beloved "Duchus";

and when about to accompany her father to India, when he was made a

judge in Bombay, she gives a pathetic picture of her last walk in the

"Duchus" with her youngest sister. Her fortitude gave way when

she heard the gate of her home closing behind her, and she wept

bitterly. "Even now," she says, after long years of absence,

"I seem to hear the clasp of that gate; I shall hear it till I die;

it seemed to end the poetry of my existence." Even the casual

visitor feels this strange spell which the place exercises upon him; and

if one has spent several summers in wandering among its romantic scenes,

the fascination becomes altogether absorbing. Season after season finds

your feet drawn towards this charming region; and no other spot can

replace it, no other scenery surpass it in its power over the

imagination and the heart. There is little reference made in The

Memoirs of a Highland Lady to the natural characteristics of

Rothiemurchus. The book does not describe the grand mountain scenery, or

give any account of the deer-stalking in the forest, or of the climbing

of the great peaks of the Cairngorm range. It is occupied entirely with

the mode of life and the social relations of this remote region at the

beginning of last century. But you feel conscious all the time of the

presence of the mountains. You feel that the grand scenery is not the

mere background of human action, but mingles with it in the most

intimate manner; and all this makes the reading of the book, so full of

artless simplicity and natural piquancy and humour, peculiarly

delightful.

The railway station for

Rothiemurchus is Aviemore, which has entirely changed its aspect in

recent years. In the old coaching days it had hardly a single building

except the inn, where the horses were baited and passengers on the way

to Inverness halted to refresh themselves. This quaint hostelry, looking

like an ancient Scottish peel, is still standing but is no longer used

as an inn. Its upper garden wall marked the height to which the Spey

rose during the celebrated Moray floods, which Sir Thomas Dick Lauder so

graphically described, when living sheep were brought across the river

and left in the trees of the garden by the overwhelming waters. The

whole country was inundated and became one great lake, and the face of

the hill behind was seamed with white roaring waterfalls, and a dense

mist filled all the air. Aviemore is now a busy junction where

innumerable trains in the summer months pass north and south, and

passengers from all parts of the world meet each other on the platforms.

A row of new villas is built along the line and a modern hotel, with a

noble background of hills and an incomparable view in front of the

Cairngorm range where all the great peaks are seen grouped together in

the most effective manner, occupies the rising ground behind.

The lands of

Rothiemurchus are bounded on the west by the Spey that flows past

Aviemore, at the foot of Craigellachie. This storied rock is not

included in the possessions of this branch of the family, although it

formed the slogan or war-cry of the whole clan, "Stand fast,

Craigellachie." It comes out boldly from the general line of hills,

and forms a most conspicuous feature in the landscape. It is composed of

mica-slate broken into ledges and rocky slopes, and in some places is

quite precipitous. It is covered mostly with purple heather,

interspersed with weeping birches and bushes of willow. The bare spaces

are clothed with bracken, whose golden tints in autumn are

indescribable; and even the hard exposed rock is weathered and frescoed

with yellow and hoary lichens. It is a rich feast of colour to the eye

at all seasons of the year, and exhibits a poetry of fleeting hues

fairer than an equal portion of sky, which it blots out, would show. By

a poetic instinct it was chosen as the symbol of the clan, and its

enduring steadfast character shadowed forth their unchanging

faithfulness amid all the strains of life. The fame of this rock in the

landscapes of their native region has always powerfully impressed the

imagination of the warlike people. It has been the scene of many a

gathering of the clan in times of war and foray; and from this central

spot the fiery cross used often to be sent round to summon the clansmen

together. Ruskin, during his visit to this region, greatly admired the

picturesqueness of Craigellachie; and he speaks thus of its

associations: "You may think long over the words ‘Stand fast,

Craigellachie,’ without exhausting the deep wells of feeling and

thought contained in them—the love of the native land, and the

assurance of faithfulness to it. You could not but have felt it, if you

passed beneath it at the time when so many of England’s dearest

children were being defended by the strength of heart of men born at its

foot, how often among the delicate Indian palaces, whose marble was

pallid with horror, and whose vermilion was darkened with blood, the

remembrance of its rough grey rocks and purple heather must have risen

before the sight of the Highland soldiers— how often the hailing of

the shot and the shrieking of the battle would pass away from their

hearing, and leave only the whisper of the old pine branches, ‘Stand

fast, Craigellachie.’"

THE Spey, as it forms the

western boundary of Rothiemurchus, has a somewhat diversified course,

being mostly swift and shallow, with extensive margins of white pebbles

in its bed; but where the high road from Aviemore crosses it by a modern

iron bridge, it expands into a deep and wide pool as black as Erebus, as

if it concentrated in itself all the peaty waters of its source in the

bogs of Drumochter, and gives one an impressive idea of the might of the

river. The Spey is not a classic stream. No poet has sung its praises,

but the murmur of its tide has found articulate expression in the

beautiful strathspeys which echo the swiftness of its pace and the swirl

of its waters. It has been associated as no other British river has been

with our national dance music. Its tributaries from Rothiemurchus, each

"a mountain power," swell its volume and add to the beauty of

the scenes through which they flow. They traverse the whole extent of

the region from east to west, from the bare, bleak heights of Braeriach

and Cairngorm to the rich green meadows which the Spey has made for

itself in the low grounds. The vast pine-forests would be oppressive

without those voices of Nature that inform the solitudes, and destitute

of those silvery pools which mirror the alders and birches. The Luineag

issues from Loch Morlich, and exposes for most of its course its

sparkling wavelets to the open sky, and the Bennie, uniting the stream

that comes from the Lang Pass and the river which carries off the

surplus waters of Loch Eunach, hides itself in the depths of the woods,

whose green folds hush the soliloquies which it holds with itself. They

form together at Coylum Bridge—which means the meeting of the waters,

or literally the twofold leap—the Druie, a capricious river that often

shifts its channel and converts much fertile land into a wilderness of

sand and gravel. With its vagaries have been connected the fortunes of

the House of Rothiemurchus, which were to be prosperous so long as the

course of the river continued the same, but disastrous should it change

its bed and work out a new channel for itself. Twice, at least, this

change has happened, when the property passed from the Shaws to the

Grants, and during the great Moray floods which devastated the whole

district.

The subject streams of

Rothiemurchus, which are the size of rivers and speak powerfully of the

great range of mountains in which they rise, gather to their generous

heart the whispered wanderings of a hundred rills. They bring down the

grand music of the mountains, the roar of the tempest, and the sigh of

the wind and the swoop of the mist in the wild corries, and the soft

murmur of the upland brook. In the rhythm of their song may be detected

all the mystic tones in which the mountains converse with one another.

The Luineag is the stillest water, for its bed is least rugged ; but the

Bennie is full of large granite boulders over which it rushes with a

swift, clear current, whose harshness is made musical by the listening

air. It is the sound of the Bennie alone that is heard, when the night

deepens the oppressive stillness and lonesomeness by hushing all other

noises, and the great mountain range looms on the horizon beneath the

stars—a gigantic silhouette, a geological dream, a vision of the

primeval ages, whose shade inundates all the landscape, and turns all

the amphitheatre of valleys black as ebony.

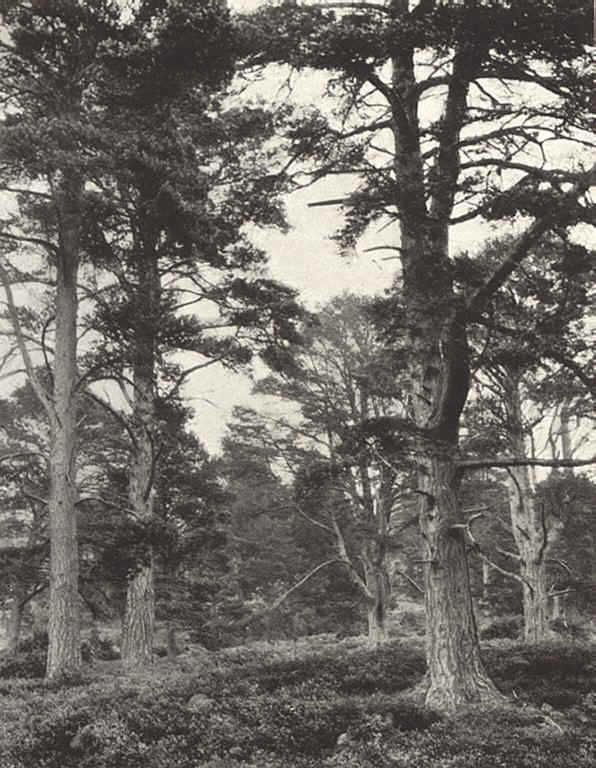

Nowhere are there more

magnificent fir-forests than those of Rothiemurchus. These forests,

about sixteen square miles in extent, are the relics of the aboriginal

Caledonian forest which covered all this region with one unbroken

umbrageous mass; and there are here and there many of the old giants

which the hand of man never planted, still growing in the loneliest

recesses, and giving an idea of what the whole primeval forest must have

been in its prime, ere the woodman, about a century and a half ago,

invaded its solitudes and ruthlessly cut down its finest trees to be

converted into timber. Most of the trees that now cover the area are of

comparatively recent planting, and though well grown do not display the

rugged picturesqueness for which the fir in its old age is so

remarkable. A plantation of young Scotch firs is as formal as one of any

other species of the pine tribe, and presents an orderly and monotonous

appearance; but as the tree grows older, it develops an amount of

freedom and eccentricity of shape which no one would have expected of

its staid and proper infancy. Its trunk loses its smoothness and

roundness, and bursts out into rugged flakes of bark like the scales on

the talons of a bird of prey or the plates of mail on an armed knight.

Its boughs cease to grow in symmetrical and horizontal lines, and fling

themselves out in all directions gnarled and contorted, as if wrestling

with some inward agony or outward obstacle like a vegetable Laocoön.

Its colour also changes; the trunk becomes of a rich tawny red, which

the level afternoon sun brings out with glowing vividness, and the

blue-green masses of irregular foliage contrast wonderfully with this

rusty hue and attest the strength and freshness of its life. Such old

firs are indeed the trees of the mountain, the companions of the storms

that have twisted their boughs into such picturesque irregularities, and

whose mutterings are ever heard among their sibylline leaves. They are

seen to best advantage when struggling out of the writhing mists that

have entangled themselves among their branches; and no grander

background for a sylvan scene, no more picturesque crown for a rocky

height, no fairer subject for an artist’s pencil exists in Nature.

While the rain brings out the fragrance of the weeping birches, those

"slumbering and liquid trees," as Wilt Whitman calls them,

that are the embodiments of the feminine principle of the woods, it

needs the strongest and hottest sunshine to extract the pungent,

aromatic scents of the sturdy firs, which form the masculine element of

the forest.

The fir is an old-world

tree. Its sigh on the stillest summer day speaks of an immemorial

antiquity. Its form is constructed on a primitive pattern. It is a relic

of the far-off geological ages, when pines like it formed the sole

vegetation of the earth. It is the production of the world’s heroic

age, when Nature seemed to delight in the fantastic exercise of power,

and to exhibit her strength in the growth of giants and monsters. It has

existed throughout all time, and has maintained its characteristic

properties throughout all the changes of the earth’s surface. It forms

the ever-green link between the ages and the zones, growing now as it

grew in the remote past, and preserving the same appearance in build and

figure.

It is a novel experience

to wander on an autumn afternoon through the unbroken forests of

Rothiemurchus. The Scotch fir usually looks its best at this time, for

the older leaves that have a yellow withered hue have been cast and the

new ones developed during the summer shine with a beautiful freshness

and greenness peculiar to the season. Wherever a breach occurs among the

trees, the ground is everywhere covered with a most luxuriant growth of

juniper bushes, some of which are of great age and attain a large size.

The grey-green of the foliage contrasts beautifully with the dark

blue-green of the firs. A dense undergrowth of heather, into which the

foot sinks up to the knee, clothes all the more open spaces. Where the

trees crowd together more closely the heather disappears, and in its

place the ground is carpeted with thickly clustering bushes of the

bilberry and cranberry, whose vivid greenness is very refreshing to the

eye. The huge conical nests of the black ant, composed of withered pine-needles,

are in constant evidence; while on the forest paths, when the sun is

shining, may be seen myriads of the industrious inhabitants passing to

and fro on their various avocations. The labour involved in the

construction of these nests must be enormous. Many of them are old and

abandoned, and over these the cranberry and bilberry bushes, which are

ever pushing forward their roots on new soil, spread themselves so that

they are half or wholly covered with a rank, evergreen vegetation,

indicating their origin only by the undulations they make in the ground.

The aromatic smell that pervades all the air is most refreshing. It

stimulates the whole system as you fill your lungs with its invigorating

breath. The sanative influence of the fir-forest is most remarkable. The

plague and the pestilence disappear, the polluted atmosphere is

deodorised, and with an effect as magical as that of the tree which

sweetened the bitter Marah of the wilderness, the presence of the Scotch

fir purifies the most deadly climate.

There is no wood more

durable than the timber of the old Scotch fir. It is proof, owing to its

aromatic odour, against insect ravages; and its texture is so hard and

compact that it resists the decay of the weather. So charged with

turpentine are the firs of Rothiemurchus, that splinters of the wood

used to be employed as candles to light up the dark nights, when the

people gathered together in some neighbour’s cottage to ply their

spinning-wheels and retail their gossip and old stories. These wood

torches when set in sconces would burn down to the socket with an

unwavering and brilliant flame, and would thus give forth a large amount

of light and heat at the same time. The darker days of late autumn were

always brightened for us by splendid fires made of old roots which had

been left in the ground when the patriarchal trees were cut down, and

which contained a vast amount of resin. I know no fires so delightful—not

even those made of the pine branches of the Vallombrosa forest in Italy—

blazing up at once, as they do, and continuing to the end clear and

bright, while emitting a pleasant fragrance which fills all the room,

and creating a most healthy atmosphere, which counteracts the noxious

influence of the rain and damp. The trees in this cold mountain climate

do not grow very rapidly, but they are valuable in proportion to the

slowness of their growth; the part of the wood which is exposed to the

sunshine being little more than sap-wood of small value, while the part

which is turned to the north, and grows in stormy situations and takes

long to mature, is hard and solid and very valuable. It is of a fine red

colour, and when cut directly to the centre or right across the grain is

very beautiful; the little rings formed of the annual layers being small

and delicate, and in perfectly even lines. The best part is nearest the

root.

About two hundred years

ago, such was the abundance of timber and the difficulty of finding a

market for it, that the laird of Rothiemurchus got only 1s. 8d. a year

for what a man chose to cut down and manufacture for his own use. The

method of making deals was by splitting the wood with wedges, and then

dressing the boards with axe and adze; saw-mills with circular saws and

even the upright hand-saw and plane being altogether unknown. A very old

room in Castle Grant is still floored with deals made in this way,

showing the marks of the adze across the boards. As a specimen of the

immense size of the trees that were cut down in the forests of Glenmore

and Rothiemurchus, there is preserved at Gordon Castle a plank upwards

of six feet in breadth. The trees when felled were made into rafts and

floated down the Spey into the sea. Large heaps of old roots dug up from

the peat-bogs and from the clearings in the forest may be seen piled up

beside every cottage and farmhouse for household fires; and everywhere

the people seem to be as dependent upon the forests as the peasants of

Norway. Indeed, what with the forests and the mountains and the

timber-houses, one might easily imagine oneself wandering in some

Dovrefield valley, instead of at the foot of the Cairngorm range.

For the contemplative and

poetic mind there is no more impressive scene than a fir-forest It is

full of suggestion. It quickens the mind, while it lays its solemn spell

upon the spirit like the aisles of a cathedral. Here time has no

existence. It is not marked as elsewhere by the varying lights and

shades, by the opening and closing of the flowers, by the changes of the

seasons, and the appearance and disappearance of various objects that

make up the landscape. The fir-forest is independent of all these

influences. Its aspect is perennially the same, unchangeable amid all

the changes that are going on outside. Its stillness is awe—inspiring.

It is unlike that of any other scene in Nature. It is not solitude, but

the presence of some mystery—some supernatural power. How vividly, in

the ballad of the "Erl King," does Goethe describe the

peculiar spirit or supernatural feeling of the forest. The silence is

expectant, seems to breathe, to become audible, and to press upon the

soul like a weight. Sometimes it is broken by the coo of a dove which

only emphasises it, and makes the place where it is heard the innermost

shrine, the very soul of the loneliness. Occasionally you hear the grand

sound of the wind among the fir-tops, which is like the distant roar of

the ocean breaking upon a lee-shore. Sometimes a gentle sigh is heard

far off how originating you cannot tell, for there is not a breath of

wind, and not a leaf is stirring; it comes nearer and waxes louder, and

then it becomes an all-pervading murmur. It is like the voice of a god;

and you can easily understand how the fir-forest was peopled with the

dim, mysterious presences of this northern mythology. In its gloomy

perspectives, leading to deeper solitudes, there seem to lurk some weird

mysteries and speechless terrors that keep eye and ear intent. You have

a strange sense of being watched, without love or hate, by all these

silent, solemn, passionless forms, and when most alone you seem least

lonely. |