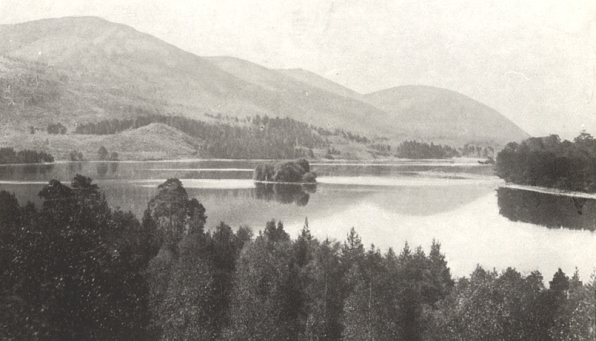

| LOCH-AN-EILAN is one of the loveliest bits

of scenery in Scotland, and the special show-place of the district. All

roads in Rothiemurchus therefore lead to it. But the high-road goes

round from Aviemore by the Doune, which is the residence of the

proprietor. Doune House is a square, modern building, substantially

constructed, in the midst of spacious parks and richly-wooded policies,

on the banks of the Spey, whose soft, cultivated beauty contrasts

strikingly with the bare rocks and brown, heath-clad mountains around. A

high mound crowned with trees lies to the east, from which the mansion

received its name. It was originally a fort, and tradition says that it

was inhabited by a brownie which faithfully served the household for

many years, probably a personification of the protection which the mound

afforded. This family seat was occupied for many years by the Duke and

Duchess of Bedford. The Duchess was the daughter of the famous Jane,

Duchess of Gordon, who lived on the neighbouring property of Kinrara,

and seems to have inherited the vivacity of disposition and the active

benevolence of her mother. A large number of the leading men of the day

were entertained in the Doune during her occupancy, among others Lord

Brougham. A dispute arose one night among the visitors as to whether the

Lord Chancellor of England carried the Great Seal about with him when he

travelled. The Duchess put the matter to the test at once, and marching

at the head of her friends to the bedroom of Lord Brougham, who was

lying ill at the time she persuaded him to imprint a cake which she had

just baked with an impression of the Seal, which, of course, settled the

question.

Rothiemurchus originally

belonged to the powerful family of the Comyns, who owned all the lands

of Badenoch. With the displacing of the Comyns is associated a tradition

of the Calart, a wooded hill to the west of the little loch of

Pityoulish. In the pass close to this loch one of the Shaws, called Buck

Tooth, waylaid and murdered the last of the Comyns of Badenoch. The

approach of the Comyns was signalled by an old woman seated on the top

of the Calart engaged in rocking the tow, and Shaw, with a considerable

force of his clansmen, sprang from his ambush and put them all to the

sword. The graves of the Comyns are still pointed out in a hollow on the

north side of the Calart, called Lag-nan— Cumineach. Unswerving

tradition asserts that this Shaw was no other than Farquhar, who led

thirty of the clan Chattan in the memorable conflict with the thirty

Davidsons of Invernahaven, on the North Inch of Perth, in 1396. His

remains were interred in the churchyard of Rothiemurchus, and a modern

flat monument with an inscription, and with the five cylinder.shaped

stones, the granite supporters of the original slab, resting upon it,

indicates the spot. Tradition says that these curious stones appear and

disappear with the rise and fall of the fortunes of the House of

Rothiemurchus. During the Duke of Bedford’s tenancy of the Doune, a

footman removed one of them to test the truth of this tradition. But he

was obliged speedily to restore it, owing to the indignation of the

people. A few days after putting back the stone upon the grave he was

drowned in fording the Spey, and his death was considered in the

district the just punishment of his sacrilege.

The Shaws held possession

of Rothiemurchus till they were finally expelled by the Grants of

Muckerach in 1570. On account of their frequent acts of insubordination

to the Government, the Lands of the Shaws were confiscated and bestowed

upon the Grants, "gin they could win them." Many conflicts

took place between the two rivals, one of them in the hollow now

occupied by the large, well-stocked garden of the House. Though defeated

and slain, the chief of the Shaws would not surrender his rights, but

even after death continued to appear and torment the victor, until the

new laird of Rothiemurchus buried his body deep down within the parish

church, beneath his own seat; and every Sunday when he joined in the

prayers of the congregation he had the satisfaction of stamping his feet

upon the body of his enemy. The last of the Shaws of Rothiemurchus was

outlawed on account of the murder of his stepfather, Sir John Dallas,

whom he hated because of his mother’s marriage to him. One day,

walking along the road near a smithy, his dog, entering, was kicked out

by Dallas, who happened to be within, when the furious young man drew

his sword and cut off Dallas’s head, with which he went to the Doune

and threw it down at his mother’s feet. The room she was in at the

time is still pointed out, and the smithy where the murder occurred is

now part of the garden. It is said that on the anniversary of the

tragedy, every August, the scent of blood is still felt in the place,

overpowering the fragrance of the flowers.

Muckerach Castle, some

three miles from Grantown, and now in ruins, was the earliest seat of

the Rothiemurchus family. The lintel-stone of the doorway was removed

and built into the wall of Doune House. It has carved upon it the date

of the erection of the Castle in 1598, and the proprietor’s arms,

three ancient crowns and three wolves’ head; along with the motto,

"In God is all my trust" Several members of the Rothiemurchus

family greatly distinguished themselves in the world of diplomacy and

politics. Sir John Peter Grant, a clever barrister, was first M.P. for

Great Grimsby and Tavistock, and in 1828 was appointed one of the Judges

of the Supreme Court of Bombay. His son was Lieutenant-Governor of

Bengal, and ultimately Governor of Jamaica, and for his valuable

services was knighted. His sister, who married General Smith, of

Baltiboys, in Ireland, wrote the charming Memoirs of a Highland Lady,

giving a social account of Rothiemurchus in the early years of last

century.

Not far from the garden

of the Doune, on a knoll which commands an extensive view, is the

mansion-house of the Polchar, where the late Dr. Martineau resided for

many years. The house has long sloping roofs and low walls, and is well

sheltered by trees from the blasts which in winter must blow with great

violence here.

From June to November the

venerable divine was accustomed to come to this place from London, and

the change no doubt helped to prolong his valuable life. When he came

first to Rothiemurchus he found that everything was sacrificed for the

sake of the deer forest. Old roads were shut up, and the public were

excluded from some of the grandest glens. Dr. Martineau set himself to

counteract this spirit of exclusiveness, and in a short time he

succeeded in securing free access to the loneliest haunts of Nature. Of

an extremely active habit of body, he climbed the heights and explored

all the recesses of the Cairngorms. In his later years, however, he

seldom moved beyond the scenes around his own door. His refined face and

earnest manner always impressed one. I shall not soon forget his look,

when I called upon him on his ninety-second birthday to offer my

congratulations and good wishes, as of one already a denizen of another

world, who had brought its far-reaching wisdom and experience to bear

upon the fleeting things of time. The family of Dr. Martineau have done

an immense amount of good in the locality, having founded a capital

library for the use of the inhabitants and visitors, and a school for

wood-carving, with an annual exhibition and sale of the articles made by

the pupils, which has stimulated the artistic taste of the young people

in a wonderful degree.

Passing the low-browed

manse, whose situation in the shadow of Ord Bàn is exceedingly

picturesque, a beautiful path at the foot of the hill conducts the

visitor to Loch-an-Eilan. A stream flows all the way from the loch

beside the path, which is over—arched by graceful birch-trees, such as

MacWhirter loved, and which he actually painted on the spot several

years ago while residing at the manse in a series of studies of the Lady

of the Woods, exceedingly beautiful and true to nature. The slender

trees here hang their long waving tresses overhead and cast cool shadows

over the white path, while the murmur of the stream soothes the senses

and makes one see visions and dream dreams. In a little while the

northern shore of Loch-an-Eilan comes in sight, embosomed among

dark-green fir-forests. It occupies an extensive hollow, overshadowed on

the east by the bare round mountain mass of Creag Dubh, one of the outer

spurs of the Cairngorm range, while on the other side rise up the grey

precipitous rocks of the Ord Bàn, clothed with birches and pines to the

top. Ord Bàn is composed mostly of primitive limestone and bands of

micaschist very much bent and twisted by the geologic forces to which it

owed its origin. It is easily ascended, and the view from the summit,

owing to its central position, is both extensive and magnificent,

including the two horizons to the north-east and south-west, with their

clothing of dark fir-forests in one direction, and of birch-woods in the

other. Loch Morlich shows itself distinctly in its wide basin glancing

in the sun, while far over the wild mountains that surge up tumultuously

in the south-west, Ben Nevis storms the sky with its broad summit.

Charles V. said of

Florence, "It is too beautiful to be looked upon except on a holy

day." The same might be said in a truer sense of Loch-an-Eilan, for

it is a sanctuary of Nature. Its beauty touches some of the deepest

chords of the heart. It is not a mere landscape, it is an altar picture.

It is a poem that gives not merely a physical or intellectual sense of

pleasure, but awakens the religious faculty within us, creating awe and

reverence like a holy hymn. One of its great charms is its

unexpectedness. It comes upon you with a sense of surprise in the heart

of the woods. Its water is the spiritual element in the dark fir-forest

It is to the landscape what the face is to the human body—that which

gives expression and imagination to it,—and therefore it lends itself

easily to spiritual suggestiveness. It is the face of Nature looking up

at you, revealing the deep things that are at the heart of it. All

around the loch are fir-woods, miles in extent, in whose depths one may

lose oneself. But here at the lochside one comes out into a wide open

space, and finds a mirror in which the whole sky is reflected. There is

a sense of freedom and enlargement. One sees more of the shadow than of

the sunshine among the fir-trees, and only bits of the blue sky appear

high up between the green tops of the trees; but here the whole heavens

are seen not only above but below, with the double beauty of reflection.

The water makes the blue sky bluer, and the golden sunshine brighter.

The sight awakens the thought that it is good to have clear open spaces

in our life, in which heaven may be brightly imaged. It is good to have

in our souls parts devoted to a different element from that of which our

life is mostly composed, in which we may have large glimpses of the

world that is above us, the spiritual and eternal world. Life must

broaden if it is to brighten. Over the narrow stream the trees arch,

shutting out the sky. To the shores of the wide lake they retreat,

leaving it open to the whole firmament.

THE little island which

gave the loch its name was originally a crannog or artificial

lake-dwelling. After affording a secure retreat for ages to the

primitive inhabitants by its wicker huts built on wooden platforms, it

finally formed a foundation for a Highland feudal stronghold of

considerable dimensions, covering all the available space and appearing

as if rising out of the water. Tradition asserts that it was originally

built by the Red Comyns, who once owned all the country round about. The

lands of Rothiemurchus having been granted by Alexander IL to Andrew,

Bishop of Moray, in 1226, the Earl of Buchan, son of Robert II., better

known on account of his ferocity as the Wolf of Badenoch, took forcible

possession of these lands, and was in consequence excommunicated. In

revenge he sacked and burned the Cathedral of Elgin. For this

sacrilegious act he had to do penance by standing barefoot for three

days at the door of the cathedral, and was restored to the communion of

the Church on condition that he would return to the Bishop of Moray the

lands he had wrested from him. This castle was one of the possessions

which the Wolf gave up. During his occupation we may well suppose that

it was the scene of many bloody deeds and crimes. It was afterwards

bestowed in lease upon the Shaws, whose chief dwelt there for more than

a hundred years without molestation. From the Shaws it ultimately passed

to the Grants of Muckerach, who have continued to hold it ever since.

One event only has been recorded since they took possession. In 1690,

after the disastrous battle on the "Haughs of Cromdale," so

long celebrated in song and dance in Scotland, the remnant of the

defeated adherents of James II., the followers of Keppoch under General

Buchan, fled to Loch-an-Eilan for refuge, and made an attempt from the

mainland to seize the castle, which was defeated by the Rothiemurchus

men under their valiant laird. A smart fire of musketry greeted them

from the walls of the castle, the bullets for which were cast by Grizzel

Mor, the laird’s wife, and they were repulsed with great loss. Since

then the castle has become a roofless ruin, whose time-stained walls,

mantled with a thick growth of ivy, add greatly to the picturesque

appearance of the loch. The stumps of the huge fir-trees, from which the

timber for the roofing and flooring of the castle was obtained, may

still be seen on the margin of the peat-bogs behind the loch from which

the people of the neighbourhood obtain their fuel, preserved as hard and

undecayed as ever after the lapse of all these centuries. It has been

persistently said that a zigzag causeway beneath the water led from the

door of the castle to the shore, the secret of which was always known

only to three persons. But the secret has never been discovered, and the

lowest state of the loch has never given any indication of the causeway.

On the top of one of the towers the osprey or sea-eagle, one of the

rarest of our native birds, used to build its nest. For several seasons

unfortunately the birds have abandoned the locality, possibly because

they were not only persecuted by the crows, which stole the materials of

their eyrie, but also frightened by the shouts of visitors on the shore

starting the curious echo from the walls of the castle. I was fortunate

enough, one recent summer, to see the male bird catching a large pike

and soaring up into the sky with it, held parallel to its body, with one

claw fixed in the head and the other in the tail. After making several

gyrations in the air, with loud screams, it touched its nest, only to

soar aloft again, still pertinaciously holding the fish in its claws. A

seagull pursued it, and rising above, attempted to frighten it, so that

it might drop the fish, but the osprey dodged the attacks of the gull,

which finally gave up the game and allowed the gallant little eagle to

alight on its nest in peace, and feed its clamorous young ones with the

scaly spoil. The fish in Loch-an-Eilan are principally pike, which often

attain a large size, especially in the eastern bays, being there so

little disturbed.

Sir Thomas Dick Lauder

realised the capabilities of Loch-an-Eilan for figuring in romance, and

has given us a vivid description of its picturesque features in his

story of Lochandhu. It combines within the small area of three

miles in circumference all the elements of romantic scenery. There is no

monotony, but, on the contrary, an infinite variety along its shores,

which form coves and inlets and low, rocky points and gravelly beaches

and open green banks. On the east side the rocky precipices rise almost

immediately from the water and fling a dark shadow over it. The path

here is seldom used, and one rarely meets a visitor in the solitude. On

the nearer or western side there is a large promontory of green

meadow-lad, standing out against the richly-wooded background of the Ord

Bàn, on which is situated an ornamental cottage with a red roof, which

in summer is frequented by crowds of visitors who come from all parts of

the country in carriages and on bicycles and make delightful picnics on

the shore. The site of this picturesque cottage was first occupied by a

house which was built by a General Grant for his widowed mother in

accordance with her own wishes. This General was originally a turnspit

in the kitchen at Doune. Quarrelling one day with the cook, the boy cut

off her hair with his knife and then ran off down the avenue at full

speed. The cook came crying to her master who shouted after him in

Gaelic, "Come back, you black thief, and get your wages."

"Wait till I ask for them," was the reply. He then enlisted as

a soldier and rose rapidly from the ranks to the highest position in the

Indian army and amassed a large fortune. He never came back to his

native glen, but he provided for all his relations and gave his mother a

pension, on which she lived happily for many years, not priding herself

very much on her son’s wonderful career, nor held in any high

consideration by her neighbours in consequence. On the promontory below

the cottage stands a rough granite monument intimating that at this

point General Rice, who did a great deal of good in the locality during

his sojourn in it, and whose portrait may be seen in almost every house,

was drowned by the breaking of the ice while skating on the loch on 26th

December 1892.

The southern end of the

loch is formed by precipitous grey rocks in the background, crowned with

dark woods, the haunt in former times of the wild cat, and surmounted at

the highest point by a monument now almost entirely concealed by the

trees, erected by her husband to the Duchess of Bedford, whose favourite

outlook was from this place. The shore here consists of magnificent

moraines covered with grass, heather and bracken, which produce in their

autumnal fading the most gorgeous effects of colour. Beyond these

immediate boundaries the open country reveals itself, taking into the

horizon the round peaks of the Boar of Badenoch and the Sow of Atholl,

and so completing the magic picture of the loch by the ethereal blue

colours of the far distance. The quieter bays are white with whole

navies of waterlilies, and when the hills and open parts of the woods are crimson with

the heather in full bloom, almost changing the water of the loch by the

enchantment of its reflection into wine and contrasting with the rich

blue-green of the fir trees, there is no finer sight to be seen in all

the land. It was feared at the time that the terrible conflagration

which ravaged the wooded shores on the eastern side some years ago would

destroy for ever much of the beauty of the loch. But while a vast

portion of the luxuriant undergrowth of the woods was burnt down on this

occasion, the loss was more than made up by the revelation of the varied

rocky features of the scene, which this undergrowth had hidden by a

monotonous covering of uniform vegetation; and now, after the rains and

storms of several winters have washed away the charred and blackened

wrecks, the recuperative powers of Nature have already spread over the

naked spaces a healing mantle of tenderest green. The woods at the head

of the loch were left altogether untouched; and here, by the side of the

charming path, which at every step discloses some new combination of

beautiful scenery, there is a number of very ancient firs, whose

gnarled, exposed roots form the banks of the path, and whose venerable

trunks and branches overshadowed the spot long before the castle on the

island was built. They are the relics of the great aboriginal Caledonian

forest; their huge red boles, armoured from head to foot with thick

scales like a cuirass, Nature’s own tallies, record in the mystic

rings in their inmost heart the varying moods of the passing seasons.

Beyond Loch-an-Eilan is a

much smaller loch where the conflagration began, and which, therefore,

suffered greater havoc in the destruction of its woods. It is called

Loch Gamhna, or the Loch of the Calves, on account of its old connection

with the creachs which used to take place along its shores. On the

eastern side there is a path through the forest called

Rathad-na-Meirlich, or "the reivers’ road," because along it

the cattle stolen by the Lochaber marauders in Speyside were driven to

the south. There is a tradition that Rob Roy himself took part in such

raids, and was no stranger in these parts. An old fir-tree, to which the

Speckled Laird of Rothiemurchus, as he was called, tied a bullock or two

during these forays, in order to procure immunity for his own herds, was

standing until it was burnt down by the recent forest fire. I possess

some fragments of this old tree, so surcharged with turpentine that they

act like torches, and burn down to the hand that holds them with a

steady bright flame. Several of the Macgregors whom Rob Roy took with

him from the south to aid in one of these expeditions remained behind

and settled in Rothiemurchus, and became allied with the laird’s

household. A tombstone preserves their memory in the churchyard. The

laird, Patrick Grant, who got the name of Macalpine because of his

friendliness to the unfortunate clan Alpine or Macgregors, was greatly

helped by Rob Roy in a time of sore need. Mackintosh, the nearest

neighbour of Grant, built a, mill just outside the west march of

Rothiemurchus, and threatened to divert a stream from Grant’s lands to

it. A fierce quarrel arose between the two lairds on this account, and

Mackintosh threatened to burn the Doune to the ground. Marching for this

purpose with his men, he suddenly encountered the forces of Rob Roy, and

fled precipitately. Rob Roy set fire to Mackintosh’s mill, and sent

him a letter in Gaelic, in which he threatened to kill every man and

burn every house on the Mackintosh estate, unless he promised to abstain

in future from molesting Rothiemurchus. A song was composed on the

occasion, entitled "The Moulin Dhu," or Black Mill, the tune

of which is one of the best reel tunes in Highland music. The Street of

the Thieves is the most celebrated of the forest paths of Rothiemurchus;

but the whole district is full of paths, used for more innocent

purposes. They are most intricate and bewildering to one who does not

know the ground, but are easily traversed by the natives. Being covered

with russet carpets of pine-needles, as if Nature herself had made them,

and not man, they are always dry and elastic to the tread. What heavenly

lights and shades from the branches overhead play upon them; and how the

westering sun with its level rays brings out the red hues, until the

forest paths glow in sympathy with the splendid .Abendglühen on

the sunset hills!

The dense mass of

vegetation in these forests strikes one with astonishment. Not an inch

of soil but is covered with a tangled growth of heather, blaeberry and

cranberry bushes and juniper; and feeding parasitically upon the

underground stems are immense quantities of the yellow Melampyrum or

cow wheat, and pale spikes of dry Goodyera, that looks like the

ghost of an orchis. Here and there in the open glades the different

species of Pyrola, or winter—green, closely allied to the lily

of the valley, send up from their hard round leaves spikes with waxen

balls of delicate whiteness and tender perfume.

The one-flowered Moneses

grandiflora, exceedingly rare, is found in some abundance in the

woods at the south-west end of the loch. And it may chance that in some

secret spot the charming little Linnaea, named after the father

of botanical science, may lurk, reminding one of the immense profusion

with which it adorns the Norwegian forests in July. The mosses are in

great variety and extraordinary luxuriance, especially the rare and

lovely ostrich-plume feather moss, which grows in the utmost profusion

on the shady knolls. The Rothiemurchus forests have always been famous

for their rare fungi, especially for their Hydna, a genus of

mushroom, which has spikes instead of gills on the under surface of its

cap. One species, the Hydnum ferrugineum, is found only in these

forests, and exudes, when young, drops of blood from its spongy

substance. There are innumerable ant-hills of various sizes, some being

enormous, and these must have taken many years to accumulate. You see

them at various stages. Some are fresh and full of life, crowded with

swarms of their industrious inhabitants. But many are old and deserted,

either half grown over with the glossy sprigs of the cranberry, or

completely obliterated by the other luxuriant vegetation.

All through the forest

you see little mounds covered with blaeberry and cranberry bushes, which

clearly indicate their origin. They were originally ant-hills. Each

particle of them was collected by the labours of these insects. If you

dig into them you will find the foundation to be composed exclusively of

pine-needles, and you can trace the tunnels and galleries made by the

ants. It is a curious association this—of plant and animal life—a

kind of symbiosis. The struggle between the two kinds of life is seen

here in a most interesting way. The wave of the undergrowth of the

forest, in its slow, stealthy, irresistible progress, encroaches upon

the ant-hills, and forms at first a ring round their base. Gradually it

creeps up their sides, and you see one-half of the ant-hill covered with

cranberry bushes and the other half retaining its own characteristic

appearance of a heap of brown fir— needles with the ants swarming over

them, busy at their work. But the vegetable wave still advances and

finally extinguishes the last spark of animal life on the mounds, and

rolls its green crest over their buried contents. In this remarkable way

the soil of the forest is formed by a combination of the labours of

plant and animal life. Looking at the vast mass of animal and vegetable

life, you feel that there is something almost terribly impressive in

this rapacious, ever-splendid Nature, tirelessly working in its

unconscious forces, antagonistic to all stability. You have an

overpowering conception of vital energy, of individual effort,

upreaching to the sun and preserving the equilibrium of Nature!

One has no idea from the

uniform clothing of the fir-forests of the extraordinary irregularity of

the ground, except here and there in the open parts and places bare of

timber, where the ups and downs of the landscape may be seen to

perfection. Huge moraines and heaps of river-drift show what elemental

forces were at work, in the later geologic periods, in moulding the

aspects of the scenery. Volcanic forces first piled up the gigantic

granite masses of the mountains on the horizon, and great glaciers

planed down their sides and deposited the debris over the low grounds

where the forest now creeps. The past here seems to be all Nature, a

theatre where only the physical powers have been operating. Human life

at the beginning must have been on too small a scale to contend with the

mighty natural forces, and was soon wiped out and effaced. In a

fir-forest, with its heather and juniper, man could find almost no

subsistence in his primitive state—no kind of scenery could have been

so inhospitable to him. And yet over the green upland slopes of

Tullochghru, where the ground has not been broken for centuries, great

quantities of burial cairns and circular dwellings and artificial mounds

or places of popular assembly show that there was here, in far-off

times, a large population. At a place called Carn-rhu-AEnachan, near the

Croft, where evidences of glacial action are most striking, there is a

green hillside which must have been the earliest clearing in the great

aboriginal forest, on which lies a half-hidden stone with three

cup-marks rudely hollowed out on its surface by a flint implement,

surrounded by faint traces of human habitation. These cup-marks are as

significant as the footprints which Robinson Crusoe saw on his lonely

island. They are the only ones I have been able to find in all the

district. They people the past for us, and give it that human interest

without which the grandest scenery becomes desolate and uninviting. They

show that where man had made a home for himself in the primeval forest,

there beside it he prepared an altar for the unknown god of his

unconscious worship. Older far, and of happier memory than the

castellated lair of the Wolf of Badenoch on Loch-an-Eilan, these

primitive cup-marks speak, not of man’s inhumanity to man, but of

man’s reverence and upward look of soul, and of the peace that binds

heaven and earth. The eternities of the past and the future are

associated with these rude symbols. We feel that the persons who scooped

them out with their flint tools were men of like passions with ourselves; that they had similar experiences and similar fears and hopes. Their

dust has utterly disappeared, their memories have altogether perished,

but what they dedicated to religion has survived, has shared in the

immortality of religion; and Nature has here preserved the first feeble

steps of primitive man along the upward path with sacred inviolability

amid the inhospitable waste. |